Metropolis (1927)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Metropolis Fritz Lang” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Fritz Lang’s 1927 expressionist science-fiction epic Metropolis was one of the most expensive and influential films of the silent era. Throughout the decades Metropolis as been regarded as the quintessential science-fiction film, and was the first feature length science-fiction film that pioneered the genre, with George Melies, A Trip to the Moon technically being the first. Made in Germany, within the UFA studios during the Weimar Period, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia, and follows the attempts of Freder, the wealthy son of the city’s ruler, and Maria, to overcome the vast gulf separating the classist nature of their city. Metropolis employed large vast sets and groundbreaking special effects to create two extraordinary worlds: the great city of Metropolis, with its beautiful Art Deco design of the expressways, airplanes, bridges and towering skyscrapers that reached the skies, and the bleak subterranean workers underground city, which included over 25,000 extras. Almost 100 years today many of its themes and designs has been duplicated, parodied, and recycled, and virtually almost every form of symbolism or dichotomy, religious or political, can be found within Metropolis: rich versus poor, man versus god, male versus female, nature versus technology, with its imagery and metaphors interpreted, whether its the upcoming rise of Nazism, or to Judeo-Christian theology. George Lucas’s blockbuster Star Wars was hugely influenced by Fritz Lang’s epic, most obviously the design of the droid of C-3PO which is a striking parallel to the android of the false Maria. The creation of the android and of its creator Rotwang are greatly reminiscent to the old laboratories of mad scientists that came out of the 30’s James Whale Frankenstein horror films, and the subplot of the creation of the false Maria, is highly similar to The Terminator machines or the Replicants in the sci-fi noir Blade Runner. [fsbProduct product_id=’794′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Unfortunately after its German premiere Metropolis was cut substantially; and large portions of the film were lost over the subsequent decades. Fortunately after 70 years, a print of Lang’s original cut of the film which included the last major missing pieces was found in a museum in Argentina, and after a long restoration process, the restored film was shown on large screens in Berlin and Frankfurt simultaneously on 12 February 2010. Greatly taking from the works of German Expressionism, Lang combined the use of stylized sets, bold shadows and lighting, dramatic camera angles, and vast bright buildings, to great a entrancing and nightmarish futuristic city. It’s bleak vision of a dystopian future of human despair, and it’s themes of the rich and greedy capitalist corporations oppressing and enslaving the poor working man, are social problems that are still relevant within our society today. According to Lang, the city of the future was synonymous with exploitation, inequality, power, corruption and greed. Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels was highly impressed with the film, and took the film’s message to heart, which isn’t so surprising since the screenplay was written by Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang’s wife at the time, a woman who would later become a member of the Nazi Party. Aesthetically, Metropolis was like nothing seen in Germany at the time, and yet the futuristic city held similarities to the vast expanding cities further west, such as New York and Chicago with Lang stating: “Metropolis, you know, was born from my first sight of the skyscrapers of New York in October 1924…”

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Metropolis Fritz Lang” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Fritz Lang’s 1927 expressionist science-fiction epic Metropolis was one of the most expensive and influential films of the silent era. Throughout the decades Metropolis as been regarded as the quintessential science-fiction film, and was the first feature length science-fiction film that pioneered the genre, with George Melies, A Trip to the Moon technically being the first. Made in Germany, within the UFA studios during the Weimar Period, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia, and follows the attempts of Freder, the wealthy son of the city’s ruler, and Maria, to overcome the vast gulf separating the classist nature of their city. Metropolis employed large vast sets and groundbreaking special effects to create two extraordinary worlds: the great city of Metropolis, with its beautiful Art Deco design of the expressways, airplanes, bridges and towering skyscrapers that reached the skies, and the bleak subterranean workers underground city, which included over 25,000 extras. Almost 100 years today many of its themes and designs has been duplicated, parodied, and recycled, and virtually almost every form of symbolism or dichotomy, religious or political, can be found within Metropolis: rich versus poor, man versus god, male versus female, nature versus technology, with its imagery and metaphors interpreted, whether its the upcoming rise of Nazism, or to Judeo-Christian theology. George Lucas’s blockbuster Star Wars was hugely influenced by Fritz Lang’s epic, most obviously the design of the droid of C-3PO which is a striking parallel to the android of the false Maria. The creation of the android and of its creator Rotwang are greatly reminiscent to the old laboratories of mad scientists that came out of the 30’s James Whale Frankenstein horror films, and the subplot of the creation of the false Maria, is highly similar to The Terminator machines or the Replicants in the sci-fi noir Blade Runner. [fsbProduct product_id=’794′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Unfortunately after its German premiere Metropolis was cut substantially; and large portions of the film were lost over the subsequent decades. Fortunately after 70 years, a print of Lang’s original cut of the film which included the last major missing pieces was found in a museum in Argentina, and after a long restoration process, the restored film was shown on large screens in Berlin and Frankfurt simultaneously on 12 February 2010. Greatly taking from the works of German Expressionism, Lang combined the use of stylized sets, bold shadows and lighting, dramatic camera angles, and vast bright buildings, to great a entrancing and nightmarish futuristic city. It’s bleak vision of a dystopian future of human despair, and it’s themes of the rich and greedy capitalist corporations oppressing and enslaving the poor working man, are social problems that are still relevant within our society today. According to Lang, the city of the future was synonymous with exploitation, inequality, power, corruption and greed. Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels was highly impressed with the film, and took the film’s message to heart, which isn’t so surprising since the screenplay was written by Thea von Harbou, Fritz Lang’s wife at the time, a woman who would later become a member of the Nazi Party. Aesthetically, Metropolis was like nothing seen in Germany at the time, and yet the futuristic city held similarities to the vast expanding cities further west, such as New York and Chicago with Lang stating: “Metropolis, you know, was born from my first sight of the skyscrapers of New York in October 1924…”

PLOT/NOTES

In late 2026, wealthy industrialists rule the vast city of Metropolis from high-rise tower complexes, while a lower class of underground-dwelling workers toils constantly to operate the machines that provide its power.

The intro of the film superimpositions a gigantic machine of pumping machine pistons- all parts thrusting, moving, pounding and turning. The 24 hour clocks in Metropolis have been redesigned, with only 10 hours on their dial. The scene cuts to a shift change and the drone-like workers begin marching in formation, taking a cage elevator down to their underground living quarters in the Workers City which is located down deep below the earths surface.

Deep below

As

deep as

lay the workers’

city below the earth,

so high above it towered

the complex named the “Club

of the Sons,” with its lecture halls

and libraries, its theaters and stadiums.

The Master of Metropolis is the ruthless Joh Fredersen, whose son Freder idles in the ‘Club of the son’ which is a above-ground sports stadium. The next scene occurs in the Eden-like Eternal Gardens, which is a pleasing erotic place for the privileged youth to play and pleasure themselves.

Freder a young, pampered, (motherless) son of a ruling, aristocratic capitalist who spends time in the Eternal Pleasure Gardens with the other children of the rich, entertained by various young women in carnival costumes, while peacocks roam around water fountains.

Freder is interrupted by the arrival of a young woman named Maria, who has brought a group of worker’ children to see the privileged lifestyle led by the rich. “Look! These are your brothers!” Maria and the children are quickly ushered away, but Freder is fascinated by Maria and descends to the workers’ city in an attempt to find her.

Freder finds himself in the machine rooms and watches in horror as one of the straining workers collapses from exhaustion, and the machine’s temperature gauge (resembling a thermometer) rises dangerously high. It overheats and explodes, propelling men through the air and sending plumes of steam skyward. When thrown to the ground, Freder hallucinates that the machine’s center has become the Moloch creature with eyes, nose, Sphinx-like front paws, and a gaping maw into which the masses of workers, now stripped and bald, are fed. Symbolically, the Moloch machine’s inexhaustible appetite consumes the human lives of its operators, who are whipped into submission and led up the stairs to their death.

Appalled by what he has witnessed, Freder runs to tell his father. “To the new Tower of Babel…to my father !” When Fredersen hears of this news he is angered that he learned of the explosion from Freder rather than his assistant Josaphat. He asks his son what he was doing down in the machine room and Freder says, “I wanted to look into the faces of the people whose little children are my brothers and my sister…Your magnificent city, Father…and you the brain of this city …And where are the people, father, whose hands built your city?”

Fredersen shows no sympathy towards him or the workers, and says, “Where they belong.” Freder says, “In the depths? What if one day, those in the depths rise up against you?” Josaphat returns with more news regarding the accident and Josaphat angrily fires him as a result. Knowing what it means to be dismissed by Fredersen, meaning he will have to go into the depths and become a worker, Josaphat attempts suicide but is stopped by Freder, who sends him home to wait for him.

Concerned by Freder’s unusual behavior, Fredersen dispatches the Thin Man to keep track of his sons movements and inform him of any new updates.

Returning to the machine rooms, Freder encounters the worker Georgy struggling with an electricity-routing device; a large clock dial. The worker must match up lighted bulbs on the clock’s rim with the two hands of the clock during his ten hour shift. As the sweating worker collapses in his arms, Freder greets him as “Brother.” The worker revives and pleads: “the machine…Someone has to stay at the machine!” and Freder sacrificially proposes to take his place at the dehumanizing, tiring machine: “Someone will stay at the machine…ME! Listen to me…I want to trade lives with you!”

Freder takes his place as the two men trade clothes, with Freder instructing Georgy to go to Josaphat’s apartment and wait for him. However, while being driven away by Freder’s chauffeur, Georgy betrays Freder’s promise and visits a red-light district instead. Finding money in Freder’s clothes, he succumbs to the temptations of the city and the night.

Meanwhile, Freder finds a map in his pocket and learns of a secret meeting from another worker as he suffers hallucinations brought on by the exhausting shift. Visual images of the dials on the machine and the ticking work clock merge back and forth. He cries out from the clock, as the crucified Christ cried out from the cross: “Father! Father! Will ten hours never end ??!!” After the painstaking shift that finally ends, Freder joins other exhausted workers as they file down into the deep catacombs, where they have been summoned.

Fredersen has received copies of the map as well, taken from the bodies of the men killed in the explosion, and takes them to the inventor Rotwang in order to learn their meaning.

There was some form of love triangle between Rotwang, a woman named Hel and Fredersen. Rotwang had been in love with Hel, who left him to marry Fredersen; she died giving birth to Freder. Fredersen tells Rotwang, “Let the dead rest in peace, Rotwang…For you, as for me, she is dead…” However, Rotwang rebuffs Joh and says, “For me, she is not dead, Joh Fredersen, for me, she lives !”

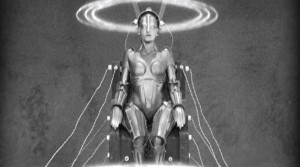

In his efforts to recreate or replace Hel with a robot, Rotwang lost his hand. He asks Joh: “Do you want to see her?” and reveals his ultimate robotic creation, a beautiful, fully-functioning android robot that is instructed to stand up, slowly walk forward, and extend its hand toward Joh. Rotwang’s goal is to turn a machine into a human, while Joh has long been treating the working class of men like machine-automatons to service larger machines. Fredersen is horrified at Rotwang’s creation.

“Isn’t it worth the loss of a hand to have created the man of the future, the Machine Man ?! Give me another 24 hours and no one, Joh Fredersen, no one will be able to tell a Machine Man from a mortal ! The woman is mine, Joh Fredersen! The son of Hel was yours!” shouts Rotwang.

Meanwhile the maps that Fredersen brought to Rotwang show the layout of a network of ancient catacombs beneath Metropolis. (Catacombs were the location where ancient Christians hid from persecution.) Rotwang descends with Joh to his basement where he opens a trap door, with stairs leading down into the catacombs. Workers are also assembling in the subterranean, darkened catacombs to see Maria and Freder is stunned to again see the Christ-like, angelic, light-haired young woman standing on an altar decorated with tall crosses and lighted candles behind her. A spiritual leader, she preaches to her raptured comrades, as Rotwang and Joh spy on the congregation from a secret vantage-point.

Maria makes an obvious analogy between the tower-building in Babel (recorded in the Biblical book of Genesis), and the workers who build and maintain Metropolis – she speaks about how the conceivers of Babel mistreated the slaves (similar to how the rulers of Metropolis are uncaringly exploiting their downtrodden workers) “Today, I will tell you the legend of The Tower of Babel…”

One worker impatiently asks “But where is our mediator, Maria ?” A spotlight shines on Freder in the crowd, believing he could fill the role. Maria answers, “Wait for him! He will surely come!” Freder and Maria gaze toward each other, and Maria approaches him and asks: “Oh mediator, have you finally come?”Freder says, “You called me — here I am!” The two kiss for the first time, and the two agree to meet in the city cathedral the next day, then part.

“Rotwang, give the Machine Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman,” Fredersen says ordering Rotwang to give Maria’s likeness to the robot so that it can ruin her reputation among the workers, but Fredersen does not know of Rotwang’s secret plan to destroy Freder as revenge for losing Hel. Rotwang chases Maria up through the catacombs and kidnaps her.

The next morning, the Thin Man catches Georgy leaving Yoshiwara, orders him to return to his post, and takes Josaphat’s address from him. Freder goes to Josaphat’s apartment in search of Georgy, but finds that Georgy never arrived. After telling Josaphat of his time in the workers’ city, Freder leaves for the cathedral, just missing the arrival of the Thin Man. Josaphat rebuffs the Thin Man’s attempts to bribe and intimidate him into leaving Metropolis; the two fight, and Josaphat escapes to hide in the workers’ city.

Freder does not find Maria at the cathedral, but he does overhear a monk preaching about the Whore of Babylon and an approaching apocalypse. Coming across statues of Death and The Seven Deadly Sins, he begs them not to harm Maria, then leaves to search for her.

Meanwhile in his laboratory Rotwang threatens the kidnapped Maria and announces his intentions, “Come! It is time to give the Machine Man your face!” Maria screams while Freder happens to be passing Rotwang’s house and ends up trapped inside until the robot has been fully transformed into Maria’s double.

In the film’s most celebrated sequence Maria is lying in a horizontally cylindrical capsule with wired connections. Rotwang’s laboratory is filled with beakers of liquid, dials, switches, flashes electrical circuits an other contraptions which makes you think of the 30’s Frankenstein films. Sparks of energy create a large ball, and form into luminous glowing rings which surround the capsule, and Maria’s face dissolves into the face of the android.

The real Maria loses consciousness as the robot becomes flesh and blood. The evil lusty Maria, (portrayed with her left eye drooping slightly) is ordered by Rotwang to the office of Master Fredersen. Freder arrives shortly after she leaves and asks where Maria is and Rotwang says she with his father. When the evil Maria arrives at Fredersen’s office he orders her his plan: “I want you to visit those in the depths, in order to destroy the work of the woman in whose image you were created!” When Freder walks in to find the two embracing in his office Freder becomes ill and faints. On his sick bed, the feverish Freder notices an invitation given to his father from Rotwang, which “requests the pleasure of your company at dinner and to see a new Erotic Dancer.”

A group of wealthy, tuxedoed men, including Joh Fredersen and Rotwang, watch the false Maria rise on a stage platform in the depraved nightclub called Yoshiwara, and begins her sexy, tempting performance of an almost nude dance. The lustful men in the audience watch in amazement…their lecherous, staring eyeballs seen in montage. The erotic dancer is portrayed as the one that the cathedral monk had spoken of, the lascivious whore of Babylon riding on a beast with seven heads.

Freder has another hallucination that the Grim Reaper statue comes to life playing a leg bone like a flute in a dance crying out, “Death descents upon the city!” The false Maria begins to unleash chaos throughout Metropolis, driving men to murder out of lust for her in Yoshiwara and stirring dissent amongst the workers.

Freder recovers ten days later and seeks out Josaphat, who tells him of the spreading trouble. Meanwhile Rotwang holds the real Maria captive, telling her about Fredersen’s ultimate plan to stir up rebellion among the workers, to have them abandon their machines. “Jon Fredersen wants to let those in the depths use force and do wrong, so that he can claim the right to use force against them. When you spoke to your poor brothers, you spoke of peace, Maria…Today, a mouthpiece of Joh Fredersen is inciting them to rebel against him.” Maria is devastated by the news of the false Maria saying, “She will destroy their belief in a mediator!” But then Rotwang informs her of his doublecross saying, “but I have tricked Joh Fredersen! Your double does not obey his will…only mine!”

At the same time, on the altar in the catacombs, the false, fanatical and beserk robotic Maria preaches a new message of protest and violent revolt to entice the working class to rebel. “Who feeds the machines with their own flesh? Let the machine starve, you fools! Let them die! Kill them! Kill the machines!!”

Freder and Josaphat proceed down into the catacombs where they find the false Maria preaching and Freder cries out, “You are not Maria! You are not Maria! Maria speaks of peace, not killing! This is not Maria!!” The workers recognize Freder as Fredersen’s son and rush him, but Georgy protects him and is stabbed to death. Fredersen orders that the workers be allowed to rampage, so that he can justifiably use force against them at a later time.

At the same time, the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s house after Fredersen breaks in to fight with him, having learned of Rotwang’s treachery.

The workers announce, “Get your women, your sons, from the worker’s city! Let no one stay behind! Death to the machines!” All the workers ralley up and follow the false Maria from their city to the machine rooms, unknowingly leaving their children behind. After abandoning their posts, the workers rip through outer iron gates, as the mob storms the M-Machine and rushes toward the Heart Machine, the central power station for Metropolis, after its foreman Grot reluctantly grants them access to it on Fredersen’s orders. “Have you gone mad ?? If the Heart Machine is destroyed, the entire workers’ city will be flooded!!” Grot shouts to the mob. But his warnings are ignored and he is overwhelmed.

The false Maria causes the Heart Machine to short-circuit until it crumbles, causing the pumps to stop turning which produces a cataclysmic flood. After running from Rotwang’s home, the real Maria comes upon the workers city where she witnesses the failure of the machines. The water ruptures through the street and begins to flood the Underground City. She gathers the children in the main square, and with help from Freder and Josaphat, lead the worker children out of danger from the waist deep water. In an intense and thrilling sequence a metal fence is blocking the children’s path of escaping. More and more children press forward as panic sets in as the water slowly rises. Finally Freder and Josaphat succeed in breaking down the metal gate, and Maria leads the last of the children to safety in the Club of the Sons.

In the machine rooms, Grot gets the attention of the wildly celebrating workers and berates them for their out-of-control actions, yelling, “Where are your children? The city lies underwater, the shafts are completely flooded! Who told you to attack the machines, you idiots? Without them you’ll all die!!” Realizing that they left their children behind in the now-flooded city, the workers go mad and yell, “It’s the witch’s fault ! Strike her dead !!” Now angry and full of grief the workers storm out to avenge themselves upon the ‘witch’ (the false Maria), who spurred them on and has since slipped away to join the revelry at Yoshiwara.

Meanwhile, Rotwang has fallen under the delusion that Maria is Hel and sets out to find her. Back at Yoshivwara’s, the false Maria celebrates and dances with the tuxedoed men, urging them, “Let’s all watch as the world goes to the devil!” The party-going revelers leave Yoshiwara’s to witness the massive destruction outside. The mob captures the false Maria (after the real Maria luckly flees from the hysterical mob) and the workers burns the false Maria at the stake. Freder watches horrified thinking that the Maria burning at the stake is the real Maria. He realizes the truth when the outer covering reveals the robotic shape underneath.

The now-insane scientist Rotwang, fearing the mob will seek retribution against him, also believes she is: “Hel -! My Hel -!!” He chases the real Maria into the cathedral, where she hangs onto a swinging bell rope, sounding another alarm. When Freder realizes that the burning witch is the false robotic Maria, he looks up at the cathedral where he sees Rotwang pursuing the real Maria, and he rushes to come to her rescue. As Rotwang and Freder fight on the cathedral’s rooftop, watched by the workers (and his horrified father) standing below, Josaphat tells Grot that the children are actually safe: “Your children…saved!!!” The workers are overjoyed by the news.

In a struggle on the cathedral’s rooftop, Rotwang loses his balance, tumbles backwards and falls to his death. Maria is saved and vindicated. Freder fulfills his mediator destiny when Maria urges Freder to be the mediator between Grot (representing the workers), and his ruling father/Master Joh Fredersen. There is the promise of a new, more equal synergy between the rulers and the ruled: “Head and hands want to join together, but they don’t have the heart to do it…Oh, mediator, show them the way to each other….” Freder joins the hand of Grot (representing Labor) and his father (representing Capital) – becoming the Mediator between the classes, united by the Heart in Love:

“THE MEDIATOR BETWEEN HEAD AND HANDS MUST BE THE HEART!”

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

Much of the style that Metropolis embodied was of German Expressionism, which was one of many creative styles and movements that came out of Germany after their defeat in World War I. UFA studios which was Germany’s principal film studio at that time, decided for the film industry to go private which largely confined Germany and isolated the country from the rest of the world. In 1916, the government had banned any foreign films in the nation, and so the demand from theaters to generate films led to the rise of film production from 24 films released in 1914 to a high 130 films in 1918.

German Expressionism and its aesthetics was first derived from German Romanticism and of architecture, painting, and of the stage, most famously from German set designers Herman Warm, Walter Rorhig, and Walter Reimann. Much of German Expressionism’s style and design expressed interior realities via exterior realities and emotionalism rather than objectivity or realism. Many films of German Expressionism used bizarre set designs with wildly non-realistic, geometrically absurd sets, along with designs painted on walls and floors to represent lights, shadows, and objects. The world that characters inhabit in a German Expressionism film are full of exaggerated landscapes and environments of abstract shapes, angles, shadows and distorted sets. The building architecture is off kilter, jagged and many of the props seem to be geometrically off-balance. This unusual visual look is intentional off course to give the viewer a feeling of inner emotional reality rather than realism. It’s unsettling sets of instability gives the feeling of claustrophobia and space collapsing around the viewer.

The actor’s in German Expressionism films usually wear heavy make-up, their acting is greatly exaggerated and their movements are jerky and unnatural to blend in with the stylistic and abstract environment. German Expressionistic’s odd and distorted style are as unrealistic as the dilution of its main character who’s narrative is a good contrast to its style as it revolves around such themes as psychology, fantasy, madness, betrayal and murder as its creators used extreme distortions in expression to show an inner emotional reality rather than realism or what was on the surface. Most films that helped categorize German Expressionism include several of Fritz Lang’s silent films most importantly Metropolis, M and Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel are also considered landmarks of German Expressionism, with some critics looking at the aesthetics of German Expressionism as the early beginnings of American film-noir.

PRODUCTION NOTES

The screenplay of Metropolis was written by Fritz Lang and his wife, Thea Von Harbou, a popular writer in Weimar Germany. The film’s plot originated from a novel written by Harbou for the sole purpose of being made into a film. The novel featured strongly in the film’s marketing campaign, and was serialized in the journal Illustriertes Blatt in the run-up to its release. Harbou and Lang collaborated on the screenplay derived from the novel, and several plot points and thematic elements — including most of the references to magic and occultism present in the novel — were dropped. The screenplay itself went through many re-writes, and at one point featured an ending where Freder would have flown to the stars; this plot element later became the basis for Lang’s Woman in the Moon.

Metropolis began filming on 22 May 1925 and the cast of the film was mostly composed of unknowns. This was particularly true of nineteen year old Brigitte Helm who played Maria and had no previous film experience. Shooting parts of the film was a draining experience for all the actors involved, due to the demands made of them by director Fritz Lang. For the scene where the worker’s city was flooded, Helm and five hundred children from the poorest districts of Berlin had to work for fourteen days in a pool of water that Lang intentionally kept at a low temperature. Lang would frequently demand numerous re-takes, and it took three days to shoot a simple scene where Freder collapses at Maria’s feet; and by the time Lang was satisfied with the footage he had shot, actor Gustav Fröhlich found he could barely stand.

Other anecdotes involve Lang’s insistence on using real fire for the climatic scene where the false Maria is burnt at the stake (which resulted in Helm’s dress catching fire), and his ordering extras to throw themselves towards powerful jets of water when filming the flooding of the worker’s city. Helm recalled her experiences of shooting the film in a contemporary interview, saying that “the night shots lasted three weeks, and even if they did lead to the greatest dramatic moments — even if we did follow Fritz Lang’s directions as though in a trance, enthusiastic and enraptured at the same time — I can’t forget the incredible strain that they put us under. The work wasn’t easy, and the authenticity in the portrayal ended up testing our nerves now and then. For instance, it wasn’t fun at all when Grot drags me by the hair, to have me burned at the stake. Once I even fainted: during the transformation scene, Maria, as the android, is clamped in a kind of wooden armament, and because the shot took so long, I didn’t get enough air.”

The effects expert, Eugen Schüfftan, created pioneering visual effects for Metropolis. Among the effects used are miniatures of the city, a camera on a swing, and most notably, the Schüfftan process in which mirrors are used to create the illusion that actors are occupying miniature sets. This new technique was seen again just two years later in Alfred Hitchcock’s film Blackmail in 1929. The Maschinenmensch — the robot built by Rotwang to resurrect his lost love Hel — was created by sculptor Walter Schulze-Mittendorff. A whole-body plaster cast was taken of actress Brigitte Helm, and the costume was then constructed around it.

A chance discovery of a sample of plastic wood (a pliable substance designed as wood-filler) allowed Schulze-Mittendorff to build a costume that would both appear metallic and allow a small amount of free movement. Helm sustained cuts and bruises while in character as the robot, as the costume was rigid and uncomfortable. The appearance of the city in Metropolis is strongly informed by the Art Deco movement; however it also incorporates elements from other traditions.

According to Patrick McGilligan’s book Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, the extras were hurled into violent mob scenes, made to stand for hours in cold water and handled more like props than human beings. The heroine was made to jump from high places, and when she was burned at a stake, Lang used real flames. Critic Roger Ebert said, “The irony was that Lang’s directorial style was not unlike the approach of the villain in his film.”

Ingeborg Hoesterey described the architecture featured in Metropolis as eclectic, writing how its locales represent both “functionalist modernism and art deco” whilst also featuring “the scientist’s archaic little house with its high-powered laboratory, the catacombs and the Gothic cathedral.” The film’s use of art deco architecture was highly influential, and has been reported to have contributed to the style’s subsequent popularity in Europe and America. The film drew heavily on Biblical sources for several of its key set-pieces. During her first talk to the workers, Maria uses the story of the Tower of Babel to highlight the discord between the intellectuals and the workers.

Additionally, a delusional Freder imagines the false-Maria as the Whore of Babylon, riding on the back of a many-headed dragon. Shooting on Metropolis lasted over a year, and was finally completed on 30 October 1926. Metropolis had its premiere at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo movie theater in Berlin on 10 January 1927, where the audience reacted to several of the film’s most spectacular scenes with “spontaneous applause”. At the time of its German premiere, Metropolis had a length of approximately 153 mins at 24 fps. Metropolis had been funded in part by Paramoun Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and UFA had formed a distribution deal with the two companies whereby they were entitled to make any change to films produced by UFA they found appropriate to ensure profitability. The distribution of Metropolis was handled by Paraufamet, a multinational company that incorporated all three film studios.

Considering Metropolis too long and unwieldy, Paraufamet commissioned American playwright Channing Pollock to write a simpler version of the film that could be assembled using the existing material. Pollock shortened the film dramatically, altered its inter-titles and removed all references to the character of Hel as the name sounded too similar to the English word Hell, thereby removing Rotwang’s original motivation for creating his robot. In Pollock’s cut, the film ran for approximately 115 minutes. This version of Metropolis premiered in the U.S in March 1927, and was released in the U.K around the same time with different title cards. The film score of the original release of Metropolis was composed by Gottfried Huppertz and it was meant to be performed by large orchestras to accompany the film during production.

The style, themes and story of Metropolis all had a huge inspiration for other sci-fi films like Gattaca, The Fifth Element, Blade Runner, Godard’s noir Alphaville, 2001: A Space Odyssey and even Tim Burton’s Batman films. “Dark city’s city design and isolated feel is also very similar, with their own underground workers that run and function the city,” stated critic Roger Ebert. “Even Batman’s villains are the descendants of Rotwang, giggling as they pull the levels that will enforce their will. The buried message is powerful: Science and industry will become the weapons of demagogues.”

Metropolis had its premiere at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo movie theater in Berlin on 10 January 1927, where the audience reacted to several of the film’s most spectacular scenes with “spontaneous applause”. At the time of its German premiere, Metropolis had a length of 4,189 metres (approximately 153 mins at 24 fps). Metropolis had been funded in part by Paramount Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and UFA had formed a distribution deal with the two companies whereby they were “entitled to make any change [to films produced by UFA] they found appropriate to ensure profitability”. The distribution of Metropolis was handled by Parufamet, a multinational company that incorporated all three film studios.

Considering Metropolis too long and unwieldy, Parufamet commissioned American playwright Channing Pollock to write a simpler version of the film that could be assembled using the existing material. Pollock shortened the film dramatically, altered its inter-titles and removed all references to the character of Hel (as the name sounded too similar to the English word Hell), thereby removing Rotwang’s original motivation for creating his robot. In Pollock’s cut, the film ran for 3170 meters, or approximately 115 minutes. This version of Metropolis premiered in the U.S in March 1927, and was released in the U.K around the same time with different title cards.

Alfred Hugenberg, a nationalist businessman, cancelled UFA’s debt to Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer after taking charge of the company in April 1927, and chose to halt distribution in German cinemas of Metropolis in its original form. Hugenberg had the film cut down to a length of 3241 meters, removing the film’s perceived “inappropriate” communist subtext and religious imagery. Hugenberg’s cut of the film was released in German cinemas in August 1927. UFA distributed a still shorter version of the film (2530 meters, 91 minutes) in 1936, and an English version of this cut was archived in the MOMA film library.

Metropolis’ original film score was composed for large orchestra by Gottfried Huppertz. Huppertz drew inspiration from Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss, and combined a classical orchestral voice with mild modernist touches to portray the film’s massive industrial city of workers. Nestled within the original score were quotations of Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle’s “La Marseillaise” and the traditional “Dies Irae,” the latter of which was matched to the film’s apocalyptic imagery. Huppertz’s music played a prominent role during the film’s production; oftentimes, the composer played piano on Lang’s set in order to inform the actors’ performances.

The score was rerecorded for the 2001 DVD release of the film with Berndt Heller conducting the RundfunksinfonieorchesteR Saarbrücken. It was the first release of the reasonably reconstructed movie to be accompanied by Huppertz’s original score. In 2007, Huppertz’s score was also played live by the VCS Radio Symphony, which accompanied the restored version of the film at Brenden Theatres in Vacaville, California. The score was also produced in a salon orchestration, which was performed for the first time in the United States in August 2007 by The Bijou Orchestra under the direction of Leo Najar as part of a German Expressionist film festival in Bay City, Michigan. The same forces also performed the work at the Traverse City Film Festival in Traverse City, Michigan in August 2009. For the 2010 reconstruction DVD, the score was performed and recorded by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frank Strobel. Strobel also conducted the premiere of the reconstructed score at Berlin Friedrichstadtpalast.

The score was rerecorded for the 2001 DVD release of the film with Berndt Heller conducting the RundfunksinfonieorchesteR Saarbrücken. It was the first release of the reasonably reconstructed movie to be accompanied by Huppertz’s original score. In 2007, Huppertz’s score was also played live by the VCS Radio Symphony, which accompanied the restored version of the film at Brenden Theatres in Vacaville, California. The score was also produced in a salon orchestration, which was performed for the first time in the United States in August 2007 by The Bijou Orchestra under the direction of Leo Najar as part of a German Expressionist film festival in Bay City, Michigan. The same forces also performed the work at the Traverse City Film Festival in Traverse City, Michigan in August 2009. For the 2010 reconstruction DVD, the score was performed and recorded by the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frank Strobel. Strobel also conducted the premiere of the reconstructed score at Berlin Friedrichstadtpalast.

Despite the film’s later reputation, some contemporary critics panned Metropolis when first released. The New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall called it a “technical marvel with feet of clay”. The Times went on the next month to publish a lengthy review by H. G. Wells who accused it of “foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general.” He faulted Metropolis for its premise that automation created drudgery rather than relieving it, wondered who was buying the machines’ output if not the workers, and found parts of the story derivative of Shelley’s Frankenstein, Karel Capek’s robot stories, and his own The Sleeper Awakes Wells called Metropolis “quite the silliest film.”

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels was impressed, however, and took the film’s message to heart. In a 1928 speech he declared that “the political bourgeoisie is about to leave the stage of history. In its place advance the oppressed producers of the head and hand, the forces of Labor, to begin their historical mission.”

Fritz Lang later expressed dissatisfaction with Metropolis. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich he expressed his reservations with Metropolis: “The main thesis was Mrs. Von Harbou’s, but I am at least 50 percent responsible because I did it. I was not so politically minded in those days as I am now. You cannot make a social-conscious picture in which you say that the intermediary between the hand and the brain is the heart. I mean, that’s a fairy tale – definitely. But I was very interested in machines. Anyway, I didn’t like the picture – thought it was silly and stupid – then, when I saw the astronauts: what else are they but part of a machine? It’s very hard to talk about pictures—should I say now that I like Metropolis because something I have seen in my imagination comes true, when I detested it after it was finished?”

In his profile for Lang featured in the same book, which prefaces the interview, Bogdanovich suggested that Lang’s distaste for his own film also stemmed from the Nazi Party’s fascination with the film. His wife at that time Von Harbou became a passionate member of the Nazi Party in 1933 and they divorced the following year after he fled Germany.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

Many film scholars, film critics, and science-fiction fans in general have tried interpreting Fritz Lang’s imagery and symbolism represented throughout the film. Virtually any form of symbolism or dichotomy can be found within the film: rich versus poor, man versus god, male versus female, nature versus technology. Metropolis presents several conflicts and struggles representing in its time, which interestingly enough was written by Lang’s wife Thea von Harbou at the time creating a sort of legacy, especially when Lang left her and fled for America when she proudly joined the Nazi Party with open arms. The film’s profusion of religious and political imagery can be traced back all through Lang’s films shaping his worldview, his ideologies and his politics. Much of the themes and images in Metropolis give a striking resemblance to Judeo-Christian theology.

For starters the geographical and sociological constructs of the film form a particular pattern familiar to those with even a passing knowledge of Judeo-Christian theology. The “metropolis” in question is built on a basis of horizontal stratification. The rich live in the uppermost levels: as the film puts it, “High in the heavens.” The workers live in the depths of the mammoth city, far below the surface of the planet, where no natural light ever reaches. This division is not unusual in literature of the turn of the century. Many speculative works from this time period feature societies — future or otherwise — where the rich live above, the poor below.

The sun-swept homes of the rich represent Heaven, Edenic pleasure gardens granting panoramic views of the city below. The sets of the upper city are exaggerated and disproportionate, architecture speaking of power and excess. Lording above the highborn creatures of the upper city is John Fredersen, father to Freder, the film’s protagonist, and as close an equivalent to the Supreme Being as Lang sees fit to offer. From his office at the very pinnacle of the city, he oversees everything, with a vast control board alerting him to any trouble. For all his technological scrutiny, however, he remains distant from his people below, aloof and disinterested in their plight. They are cogs in his grand design, and he is an Old Testament god, quick to wrath and scornful of disobedience.

Below this paradisal upper city, hordes of workers toil and die so that the machinery of the great city may roll on uninterrupted. Freder calls the mechanical Juggernaut that powers the upper city “MOLOCH,” a Canaanite word meaning “king.” Moloch was a god of the Ammonites, and not a kind god. Moloch’s worshippers engaged in the ritual sacrifice of children, specifically sacrifice by fire. The vast machine churns in the depths of the city, belching clouds of steam onto the masses of workers who know neither hope nor rest. It takes little imagination to visualize these enormous factories as the biblical underworld wrought not in fire and brimstone, but in molten steel and smoke-blackened iron. Indeed, Freder imagines just such a sight after he witnesses an accident that kills several workers; his mind conjures up visions of helmeted demons feeding legions of helpless worker-slaves into the ravenous maw of the demonic machine. More sacrifices tossed into the ever-hungry belly of Moloch, to be consumed in fire and smoke and ash.

When not “on the clock,” the cogs in this particular machine dwell in the worker’s city, a gray and desolate ghetto located far below the other two domains. This is the place where the workers eat and sleep and pursue whatever vain efforts they may find time for in between grueling shifts. Contrary to some Christian traditions, Metropolis does not place this realm, analogous to our own physical reality, between heaven and hell, but rather below them both. Perhaps this is because it represents a physical reality, whereas “Heaven” and “Hell” belong to the spiritual. The worker’s city also houses beneath it a labyrinth of ancient catacombs reminiscent of those used by early Christians to meet in secret, the walls stacked with the generations of dead who built the city, now forgotten and desiccated. It is here amongst the dead that the workers find a glimmer of hope, a prophet whose revolutionary words dare to suggest a meeting of worker and master, a unification as equals.

Preaching from an abandoned chapel deep within those catacombs, the speeches of Maria evoke parallels to John the Baptist’s own sermons from the wilderness, where he foretold the coming of Jesus while clothed in camel skins and subsisting on locusts and honey. Like John, Maria preaches of the coming of a “savior” who will rescue his people by uniting the “head” of the upper city dwellers with the “hands” of those below.

Her words do not fall on deaf ears: she attracts hundreds of workers, more with each meeting. She speaks of patience, and of hope of a better way of life, but also denounces thoughts of open revolt or violence. One night, she tells the workers the story of the Tower of Babel, a story that resonates quite strongly with the city’s weary residents. As with Babel, Maria explains, their city is ruled by those above, who have no compassion for those below. Reconciliation must come through a mediator, a third party capable of bridging that gap. A messiah is needed.

From her first appearance, Maria also evokes the Virgin Mary, entering Freder’s garden (a garden of Eden) surrounded by children, her hands extended over them in saintly grace. From this first meeting, she is responsible — indirectly, at first — for bringing Freder down to the level of the people, away from his home in paradise. It is notable that this first appearance to Freder occurs directly on the heels of Freder’s dalliance with the nameless maiden in the garden. If the scantily clad woman is Freder’s Mary Magdalene, then Maria is clearly Freder’s Mary. Assuming the roles of both prophet and mother, Maria first foretells of Freder/Christ’s coming, and then is herself the agent of that arrival when Freder descends to the lower city in pursuit of her.

It is no coincidence that the robot built by Rotwang takes the form of Maria, an evil doppelganger that spreads anger and fear, the antithesis of Maria’s vision of peace. Our first glimpse of the robot finds it beneath an inverted, five-pointed star, a pentacle — a sigil long associated with ceremonial magic, especially that involved in summoning outside forces. Indeed, Rotwang’s android does seem to carry within its husk something more sinister than simple ones and zeroes. It springs into being from the mind of man, rather than divine guidance, formed not of Adam’s rib; its unnatural birth instead costs Rotwang his hand. . . a sacrifice he does not regret.

As the robot is shaped into the image of Maria, a heart begins pulsing within its metallic form. The real Maria has foretold that the one who will unite the city must be the “heart” to unite head and hands, and the robot is a dark reflection of this. In the robot we have an unholy communion, both Antichrist and Whore of Babylon, Beast of Revelations and Horseman of the Apocalypse, a being that can bring only ruin to those who follow it. Visiting the city’s red light district, this false Maria hypnotizes a crowd of aristocratic men with a fevered, near-orgiastic dance, like something from the pleasure gardens of Sodom and Gomorrah. As Freder looks on, visions overtake him, images of the Seven Deadly Sins attacking the city, foreshadowing the dangers yet to come. Though he does not yet understand that this is not the Maria he knows, he senses the doom this woman carries with her.

After seducing the upper classes, the robot perverts the trust Maria has formed with the workers, leading them down a path of deception and into cataclysm. She incites them to attack the machines beneath the city, and the resulting shockwave of violence climaxes in nothing less than a flood of biblical proportions, an apocalyptic deluge that sweeps over the workers’ city and threatens to kill all their children. Only Freder’s intervention saves the children.

Freder is at the center of this disaster, as he is at the center of the entire film. The only begotten son of the city’s “god,” Freder first becomes enamored of the lovely and pure Maria, and then horrified by the plight of the people below him. Freder’s descent into their world mirrors the story of Christ. His fascination with Maria allows her to metaphorically birth him into this world he had not previously considered and could not have understood.

As Freder stands in the machine room, confronted for the first time with the plight of his “brothers,” as he calls them, he is struck with horror at the sight of his people, stranded in an all-too-real Hell. This is the first time Freder faces the truth of the workers’ lives, and Lang uses every cinematic trick available to represent his inner turmoil. The camera work in this sequence alternates between shots of the desperate and weary workers slaving away at the machines, and closer views of Freder, of his disgust at the sight. A machine explodes, tossing workers through the air like dolls, and Lang shakes the camera as the blast knocks Freder to the ground. Lang makes clear that Freder felt that blast, as surely as the workers did. At that instant, Freder can no longer remain an outsider; he has become tied to their world.

After his pleas to his father to lessen the workers’ load fall on deaf ears, Freder decides that he himself must take up the yoke of one of the workers. As with Christ’s acceptance of a physical avatar, Freder’s quest is motivated partly out of sympathy for the people below him, and partly out of curiosity to experience the world as they do. After a grueling ten-hour shift that stretches mercilessly, Freder collapses at the foot of the horrific clock-like machine, arms outstretched — symbolically crucified to the machine that has enslaved the workers. Freder’s cries of “Father, I never knew ten hours could be so long!” mirror Christ’s own agonized “Father, Father, why have you forsaken me?”

But, as with Christ’s death on the cross, Freder emerges from the torture of the machine reborn, with a newfound passion for the plight of the workers and a newfound determination to bring it to an end. It is he who sets out to rescue Maria, and it is he who risks his own life to journey into the workers’ city, even as it fills with floodwaters loosed by those who inhabit it. And, in the end, it is Freder alone who can bridge the gap between the workers and their overlord, just as Christ bridges the gap between God and man in Christian theology.

Freder serves as the binding force between two diametrically opposed elements, elements that could never otherwise be reconciled. Lang calls these forces the “head and the hands,” and the binding force of Freder, he calls “heart.” The parallel between these forces and the tenets of Christian theology is impossible to ignore.

I do not want to suggest that Lang intended Metropolis as a religious allegory; that is not the point at all. Rather, Lang understood the power of symbols, especially symbols relating to subjects close to the viewer’s heart, such as politics, economics. . . and religion. Lang made skillful and effective use of the basic Christian symbols, perhaps even working at a subconscious level. Through this, Lang added a depth and nuance to the film that evokes powerfully ingrained emotions, even in this more secular age.

-David Michael Wharton

Metropolis is concerned with wider cultural and political issues, evidenced visually as well as thematically. The film’s social preoccupations have been described as a commentary on the political situation that existed in Germany at the time, but also served as a warning of where Germany was heading in the future.

The film was made during Germany’s Weimar Republic; the country’s first attempt at creating a democracy in the very difficult years following the First World War. The economic and political aftermath of Germany’s defeat led to hyperinflation, revolts on the streets and a general sense of anxiety and dissatisfaction with the ruling powers.

For the German people, cinema offered a means of escaping the hardships of daily life. Historical and sci-fi genres were popular at the time for their representations of other worlds and distant times. For Lang to make a realist film that dealt directly with the troubles of the day would not have pleased German audiences. Instead, he tapped into Germany’s power struggles, issues of poverty and conflict, and fears for the future, using an entirely constructed and heavily stylised futuristic landscape filled with symbolism and metaphors to convey.

The anxieties of the time are deeply felt in Metropolis, but Lang claimed he was also ‘looking at Germany in the future’ when he made the film. The futuristic aspect of the film suggests there may have been a sense of conflict in relation to the state of contemporary Germany, and where the nation was heading on its road to modernization.

Metropolis’s horrifying vision of a dystopian future and it’s themes of the rich and greedy capitalist corporations oppressing and enslaving the poor working man, are very real themes that are still relevant within our society today. The film explores the themes of the Industrial Revolution, which was the transition to large manufacturing corporations and the rise of machines and technology. Because of this take over of machinery, millions of hard working folks were put out of their profession and of their respectable trade. This rise of greedy capitalist corporations, gradually changed the role of the working man. This transition made the working man simply ‘hands’ and a ‘body’, losing their respectabilities of their positions and their identity, eventually succumbing to the form of a job that requires absolutely no identity or talent involved. Before the rise of the Industrial Revolution, the working man had a pride in their trade or profession which acquired a form of talent and prestige. The working man had a label, or an identity, for instance: the carpenter, the farmer, the merchant, ect. In the opening shot of Metropolis the worker’s are drone-like figures with no unique identity, that robotically begin to march in formation, similar to a herd of sheep, symbolizing more machine-like ‘bodies’ and less individual human beings.

Aesthetically, the thriving, bustling urban space of Metropolis was like nothing seen in Germany at the time. However, the futuristic city held similarities to the vast physical dimensions of rapidly expanding cities further west, such as New York and Chicago. The film explores the decadence and delights of modern cities but also the inequality and social problems that exist beneath the glossy surface. The futuristic city of Metropolis is built quite literally on inequality; to Lang, the city of the future was synonymous with exploitation, power, corruption and greed: “Metropolis, you know, was born from my first sight of the skyscrapers of New York in October 1924…while visiting New York, I thought that it was the cross-roads of multiple and confused human forces, blinded and knocking into one another, in an irresistible desire for exploitation, and living in perpetual anxiety. I spent an entire day walking the streets. The buildings seemed to be a vertical sail, scintillating and very light, a luxurious backdrop, suspended in the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotise. At night, the city did not simply give the impression of living: it lived as illusions live. I knew I should make a film of all these impressions.”

The uprising of the workers conveys a very significant and important political message about inequality in society and the future of modern capitalism. Metropolis exposes the very mechanics of capitalism – from the labouring masses at the bottom, to the powerful elite at the top. Symbolism is also an important part of Metropolis. It has been suggested that Freder can be regarded symbolically as the cinema audience member in Weimer Germany, who has witnessed the horrors of the First World War, the aftermath, and then has observed Germany descend into political chaos.

They’re several themes in Metropolis that are still relevant in today’s society, like the ignorance of mob mentality and violently taking the law into your own hands. In Metropolis, mob mentality is historically relevant on Fritz Lang’s thoughts on the time and place of German society in the late 1920’s. Metropolis portrays the workers in the film as slightly stupid people who could be easily manipulated to do almost anything. Many of these metaphors on violence and mob mentality can be slight foreshadowings on the rise of Nazism, in which a mob or a large number of people could influence an individual’s moral decision making and have a person mindlessly go through or carry out something that they could never do alone, but only with others. First off, the workers all act similarly by going down to the catacombs and intently listening to Maria talk about her so-called ‘Mediator.’ Then, Lang emphasizes this ignorant thinking of mob violence when the workers listen to the false Maria talk about rising up against the machines and using violence.

After a short period of time the false Maria already has the workers all riled up and angry for whatever reason, and soon enough they are in a pack creating havoc and destruction within their own Underground City. What I find fascinating is all the while the workers stupidly destroy the central power station which causes the streets of Metropolis to flood, they completely forget about their own children, and ignorantly place them in extreme danger. Interestingly enough, (and I find this quite humorous) when they realized they’ve been deceived, they don’t accept that they were wrong and admit to their mistakes. They instead point the finger at the false Marie and blame her for their stupidity. Immediately their mob violence intensifies and they begin to hunt her down so they can tie her up and burn her at the stake for making them do something which was clearly their own doing. Some of the ideas in Metropolis seemed to frightfully echo the ignorant themes of Leni Riefenstahl’s pro-Hitler propaganda film Triumph of the Will. Lang was clearly interesting in the idea of mob mentality since he used it again in his 1931 masterpiece M, and years later when making his first American film titled Fury starring Spencer Tracy.

Fritz Lang is one of the greatest directors of all time and along with the style of German Expressionism, he developed some of the greatest films in the world. Many of the early silent films Lange created included his thriller Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, and his fantasy epic Die Nibelungen. In 1931 Lang created his masterpiece M which not only was his very first sound film, but it is a film that is credited with created two separate genres: The serial killer genre and the police procedural. A lot of people believe M paved its way into film noir in the early 40’s in America, for which I’m not at all surprised since Lang prospered in the states making some of the greatest noir films from the early 40s to the early 50s.

Lang’s next film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in 1933 was a sequel to his famous character Dr. Mabuse in the silent classic The Gambler. This story continued Dr. Mabuse’s story where he’s now in an insane asylum and working his crimes from the inside, but the difference in that film is that the character knows how to brainwash and hypnotize his victims to commit horrible crimes which was unmistakably thought of as Nazism. When Lang released his film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse it was banned in Germany by the censors. When Adolf Hitler acquired power, Joseph Goebbels became minister of the Ministry of Propaganda and offered Lang full control of the nation’s film industry if he would come on board with the Nazis, so Fritz Lang instead fled on a midnight train to America. In an amazing interview with Fritz Lang by William Friedkin on the blu ray Criterion of M, Fritz Lang details the night he fled Germany; which is absolutely spellbinding.

When Lang arrived in the states he created some of the very best American noir films including You Only Live Once with Henry Fonda, which is slightly based on Bonnie and Clyde, Fury with Spencer Tracy, which similar to the themes of Metropolis which explores the ignorance of mob violence and what it can escalate to, Scarlett Street with Edward G. Robinson, who plays a wealthy man being conned by a beautiful woman and his best American film The Big Heat with Glenn Ford, which is about a cop seeking revenge on the murder of his wife. I find it interesting how Lang later on went and established the noir genre, when the false Maria, in Metropolis was an early form of the femme fetale. The dangerous and alluring woman who could seduce and lead men into dangerous, and deadly situations.

The story of Metropolis tells a simple story about two segregated halves of a city, one is the wealthy and pampered citizens up on the surface, and the other are the slaves in the depths of the underground; ironically the two are ignorant of one another until young Freder exposes the oppression. The city of Metropolis is run by the ruthless Joh Fredersen, who is a businessman and cruel dictator. When Jon Fredersen’s son Freder first sees the beautiful Maria he is immediately entranced by her beauty when catching her in the Adam and Eve like Pleasure Gardens. She emerges from underground, bringing a group of worker children to the surface which causes Freder to follow her, which is how he makes the astonishing discovery of the workers underground, (It took him all these years to make this discovery?) and is greatly shocked at the horrendous abuse they endure through their work.

There is an amazing sequence where Freder descents into the depths and attempts to help his workers, by straining to move heavy dial hands and levers back and forth, in a underground power plant like environment. None of what the workers do underground make any logical sense, and yet symbolically it is quite obvious: They are puppets who are controlled and ordered to put their hands on the gears of a clock, a clock which dictates their lives. In one sequence Freder finds himself in the machine rooms and watches in horror as one of the straining workers collapses from exhaustion, and the machine’s temperature gauge which resembles a thermometer rises dangerously high, and eventually overheats and explodes, injuring several of its workers. In a fascinating subplot of the story, a wise mad scientist Rotwage is ordered by Fredersen to destroy Maria’s reputation by creating a robot version of herself (which originally was the image of his dead love Hel) that will stir up a rebellion among the workers, to have them abandon their posts and rise up against the machines.

They’re several visually stunning sequences in the film, that it’s nearly impossible to list all of them. The sequence near the beginning of the film immediately comes to mind, where Freder encounters a worker struggling with an electricity-routing device which is of a large clock dial. The worker has to match up lighted bulbs on the clock’s rim with the two hands of the clock during his ten hour shift, and Freder runs over just in time to take his place and help him complete his shift. There is the iconic Tower of Babel speech where the workers assemble in the subterranean catacombs to see her leader Maria as a angelic Christ-like figure standing on an altar decorated with tall crosses and lighted candles behind her, preaching to her comrades about the supposed mediator that will help free the workers (Obviously the mediator is revealed to be Freder). There are the many hallucinations of Freder, my favorite being the center of the machine that runs the machine room, which transforms into a Moloch creature with eyes, nose and Sphinx-like front paws, as its gaping mouth consumes the human lives of its workers, who are whipped into submission and led up the stairs to their death. The extraordinary transformation sequence where Maria lies in Rotwang’s laboratory which is filled with beakers of liquid, dials, switches, flashes, electrical circuits and other contraptions which immediately makes you think of the 30’s mad scientist Frankenstein films. Maria is placed in a horizontally cylindrical capsule with wired connections hooked up to an android. Suddenly sparks of energy create a large ball, and form into luminous glowing rings which surround the capsule, and Maria’s face dissolves into the face of the evil Maria android (portrayed always with her left eye drooping slightly). My favorite sequence in the film is when the false Maria rises on stage and performs a sexy dance at a depraved nightclub, as her sexy, tempting performance is lusted by the men in the audience as they watch in amazement with a montage of gazing lecherous eyeballs, before violently turning on one another. Fritz Lang was a visionary genius as I stood there under the spell of Metropolis completely hypnotized and in awe by its extraordinary visuals. While viewing the ‘complete version’ of Metropolis which includes about 25 more minutes of extra footage, a lot of the new footage that was added in was greatly fascinating. I noticed several new fascinating scenes in the complete version, which gave a much greater detail on the tension and emotional resonance of the conflict between the wealthy dictating capitalist and the rebellious subterranean laborers that finally uprise and fight back. Than it got down to the most important missing footage of the film which is included in the last suspenseful act which involves the flooding of the worker’s city. When the false Maria has all the workers rally up and follow her to the machine rooms, they rip through the outer iron gates and storm the M-Machine which is the central power station and short circuit it. This causes the pumps to stop turning which produces a cataclysmic flood, which ruptures through the street and begins to flood the Underground City. Maria gathers the worker children in the main square, and leads the worker children out of danger from waist deep water. In an intense and thrilling sequence a metal fence is blocking the children’s path of escaping. More and more children press forward as panic sets in as the water slowly rises higher. Finally Freder and Josaphat succeed in breaking down the metal gate, and Maria courageously leads the last of the children to safety. Most of this new footage involved the rescuing of the underground children in the horrific flood, and this sequence is absolutely breathtaking as several of these scenes looked extremely dangerous to shoot. It was astonishing to see such an exciting set piece of the story finally added back in, which not only makes the story as a whole flow much better, but it gives more dimension to the character of Maria, presenting to the audience a courageousness woman and her love for the children of the city. Today, critics believe Metropolis to be one of the greatest films of all time and many hail it as a masterpiece. Film critic Roger Ebert noted that “Metropolis is one of the great achievements of the silent era, a work so audacious in its vision and so angry in its message that it is, if anything, more powerful today than when it was made.” The complete cut of Metropolis is finally the film Fritz Lang attended all of us to see, but the only unfortunate thing is it just took over 80 years for us to see it. There’s not much more praise I can say about Metropolis that anyone else hasn’t already said about the film. It’s one of the most important films of all time and one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was to the technical aspect of dramatic films as Metropolis is to the science-fiction genre.

They’re several visually stunning sequences in the film, that it’s nearly impossible to list all of them. The sequence near the beginning of the film immediately comes to mind, where Freder encounters a worker struggling with an electricity-routing device which is of a large clock dial. The worker has to match up lighted bulbs on the clock’s rim with the two hands of the clock during his ten hour shift, and Freder runs over just in time to take his place and help him complete his shift. There is the iconic Tower of Babel speech where the workers assemble in the subterranean catacombs to see her leader Maria as a angelic Christ-like figure standing on an altar decorated with tall crosses and lighted candles behind her, preaching to her comrades about the supposed mediator that will help free the workers (Obviously the mediator is revealed to be Freder). There are the many hallucinations of Freder, my favorite being the center of the machine that runs the machine room, which transforms into a Moloch creature with eyes, nose and Sphinx-like front paws, as its gaping mouth consumes the human lives of its workers, who are whipped into submission and led up the stairs to their death. The extraordinary transformation sequence where Maria lies in Rotwang’s laboratory which is filled with beakers of liquid, dials, switches, flashes, electrical circuits and other contraptions which immediately makes you think of the 30’s mad scientist Frankenstein films. Maria is placed in a horizontally cylindrical capsule with wired connections hooked up to an android. Suddenly sparks of energy create a large ball, and form into luminous glowing rings which surround the capsule, and Maria’s face dissolves into the face of the evil Maria android (portrayed always with her left eye drooping slightly). My favorite sequence in the film is when the false Maria rises on stage and performs a sexy dance at a depraved nightclub, as her sexy, tempting performance is lusted by the men in the audience as they watch in amazement with a montage of gazing lecherous eyeballs, before violently turning on one another. Fritz Lang was a visionary genius as I stood there under the spell of Metropolis completely hypnotized and in awe by its extraordinary visuals. While viewing the ‘complete version’ of Metropolis which includes about 25 more minutes of extra footage, a lot of the new footage that was added in was greatly fascinating. I noticed several new fascinating scenes in the complete version, which gave a much greater detail on the tension and emotional resonance of the conflict between the wealthy dictating capitalist and the rebellious subterranean laborers that finally uprise and fight back. Than it got down to the most important missing footage of the film which is included in the last suspenseful act which involves the flooding of the worker’s city. When the false Maria has all the workers rally up and follow her to the machine rooms, they rip through the outer iron gates and storm the M-Machine which is the central power station and short circuit it. This causes the pumps to stop turning which produces a cataclysmic flood, which ruptures through the street and begins to flood the Underground City. Maria gathers the worker children in the main square, and leads the worker children out of danger from waist deep water. In an intense and thrilling sequence a metal fence is blocking the children’s path of escaping. More and more children press forward as panic sets in as the water slowly rises higher. Finally Freder and Josaphat succeed in breaking down the metal gate, and Maria courageously leads the last of the children to safety. Most of this new footage involved the rescuing of the underground children in the horrific flood, and this sequence is absolutely breathtaking as several of these scenes looked extremely dangerous to shoot. It was astonishing to see such an exciting set piece of the story finally added back in, which not only makes the story as a whole flow much better, but it gives more dimension to the character of Maria, presenting to the audience a courageousness woman and her love for the children of the city. Today, critics believe Metropolis to be one of the greatest films of all time and many hail it as a masterpiece. Film critic Roger Ebert noted that “Metropolis is one of the great achievements of the silent era, a work so audacious in its vision and so angry in its message that it is, if anything, more powerful today than when it was made.” The complete cut of Metropolis is finally the film Fritz Lang attended all of us to see, but the only unfortunate thing is it just took over 80 years for us to see it. There’s not much more praise I can say about Metropolis that anyone else hasn’t already said about the film. It’s one of the most important films of all time and one of the greatest science-fiction films ever made. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was to the technical aspect of dramatic films as Metropolis is to the science-fiction genre.