Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

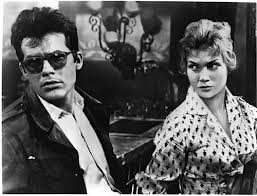

Andrzej Wajda's Ashes and Diamonds is looked at as one of the greatest of all postwar East-Central European films, and also the most vital work of the Polish School, completing what many believe to be Wajda's war trilogy, which followed A Generation and Kanal. It's extraordinary how much controversy carried Ashes and Diamonds within Poland itself, as the film stemmed from several conflicting goals: to deal with the Polish Home Army's resistance against the incoming Soviet-backed Communist regime, and yet to satisfy both the Polish audience who held that army dear and a Communist party that wielded powers of censorship, even though it had renounced a Stalinist rigor of repression. Criticize the Home Army too strongly and the audience will turn on you; offend the regime, and your film might be destroyed or even aborted. (It was even reported that Wajda himself had efforts to remove Maciek's death sequence going right down to the wire of the first screening.) Ashes and Diamonds was based on the 1948 novel by Polish writer Jerzy Andrzejewski, and yet more Poles took Wajda's film much more personally than they had with Andrejewski's novel. Wajda argued that it was because the films visuals offered much more a leeway for an ambiguity which could ultimately fool the censors, that and Zbigniew Cybulski's electrifying performance as Maciek Chelmick, portraying a man's twenty-four hour transformation which was the hinge connecting the end of one war (world) to the start of a new (civil) one. [fsbProduct product_id='734' size='200' align='right']When Wajda was filming Ashes and Diamonds he was working right in the aftermath of the liberalizing 1956 'thaw', otherwise known as 'the Polish October.' And yet there were limits to the freedom it brought, and the very recent nature of that change, combined with the artist's canny awareness of the possibility of a renewed freeze, which makes it not surprising that the film’s opening and ending, in which Maciek stumbles up unglamorously in a fetal position, should be so compatible with the state's denunciation of the Home Army. And yet it's the fascinating creation of the character of Maciek Chelmick, with his dark glasses and smooth exterior that took European audiences by storm. Maciek blends the existentialism of the gritty resistance, and the existentialism of fashion and coolness; as which he was often called Poland's James Dean, portraying a toughness and boyish vulnerability, which seemed to tackle an essence of both James Dean and Marlon Brando. Maciek has been ordered to assassinate an incoming commissar, but a mistake stalls his progress, which eventually leads him to meet a beautiful barmaid, who if only for a short period of time, will give him a glimpse of a more peaceful and happier existence, and of a life that could have been.

Andrzej Wajda's Ashes and Diamonds is looked at as one of the greatest of all postwar East-Central European films, and also the most vital work of the Polish School, completing what many believe to be Wajda's war trilogy, which followed A Generation and Kanal. It's extraordinary how much controversy carried Ashes and Diamonds within Poland itself, as the film stemmed from several conflicting goals: to deal with the Polish Home Army's resistance against the incoming Soviet-backed Communist regime, and yet to satisfy both the Polish audience who held that army dear and a Communist party that wielded powers of censorship, even though it had renounced a Stalinist rigor of repression. Criticize the Home Army too strongly and the audience will turn on you; offend the regime, and your film might be destroyed or even aborted. (It was even reported that Wajda himself had efforts to remove Maciek's death sequence going right down to the wire of the first screening.) Ashes and Diamonds was based on the 1948 novel by Polish writer Jerzy Andrzejewski, and yet more Poles took Wajda's film much more personally than they had with Andrejewski's novel. Wajda argued that it was because the films visuals offered much more a leeway for an ambiguity which could ultimately fool the censors, that and Zbigniew Cybulski's electrifying performance as Maciek Chelmick, portraying a man's twenty-four hour transformation which was the hinge connecting the end of one war (world) to the start of a new (civil) one. [fsbProduct product_id='734' size='200' align='right']When Wajda was filming Ashes and Diamonds he was working right in the aftermath of the liberalizing 1956 'thaw', otherwise known as 'the Polish October.' And yet there were limits to the freedom it brought, and the very recent nature of that change, combined with the artist's canny awareness of the possibility of a renewed freeze, which makes it not surprising that the film’s opening and ending, in which Maciek stumbles up unglamorously in a fetal position, should be so compatible with the state's denunciation of the Home Army. And yet it's the fascinating creation of the character of Maciek Chelmick, with his dark glasses and smooth exterior that took European audiences by storm. Maciek blends the existentialism of the gritty resistance, and the existentialism of fashion and coolness; as which he was often called Poland's James Dean, portraying a toughness and boyish vulnerability, which seemed to tackle an essence of both James Dean and Marlon Brando. Maciek has been ordered to assassinate an incoming commissar, but a mistake stalls his progress, which eventually leads him to meet a beautiful barmaid, who if only for a short period of time, will give him a glimpse of a more peaceful and happier existence, and of a life that could have been.

PLOT/NOTES

In an unnamed small Polish town on May 8, 1945, the day Germany officially surrendered, Maciek (Zbigniew Cybulski) and Andrzej (Adam Pawlikowski) are Home Army soldiers who have been assigned to assassinate the communist Commissar Szczuka. The opening presents Maciek and his companion Andrzej lounging in the grass, as the camera comes down from a chapel's cross suggesting a fallen world. A little girl asks one of the two men if they could open the chapel door for her. Suddenly a car pulls up and Maciek quickly fires at the men in the vehicle, believing he is asssinating the newly installed local party secretary Szczuka. Maciek's tommy-gun eliminates one while running at the chapel's door, causing the man's suit to engnite in flames. Unfortuantely Maciek and Andrzej realize only afterwards that the two men they killed were two civilian cement plant workers named Smolarski and Gawlik. Drewnowksi, a double agent who works inside along with Szczuka, and who tipped off Maciek and Andrzej, becomes extremely frightened when coming to the realization of the mistake, as he cowardly runs off so he is not seen when authrorities arrive.

Szczuka arrives to where the two cement plant workers were killed, as Szczuka says to his right hand man, "I think it was you and I that was supposed to be lying there." Many of the townspeople in the area arrive and they angrily ask Szczuka, "Excuse me comrade. So you're the party secretary who was coming here? I wanted to ask you something. Not just me, but all of us. Can you tell us how long people will have to die like this? This isn't the first time." Szczuka cuts in saying, "And it won't be the last. I'd be a bad communist, comrades, if I were to reassure you like a bunch of naive kids. The end of the war isn't the end of our fight. The fight for Poland and what kind of country its to become has only just begun. Today or tomorrow, or the day after, any one of us could die."

Maciek and Andrzej quickly flee after the murders and head to the town's leading hotel in Monopol. The hotel banquet hall is currently throwing a grand fête which is being organized for a newly appointed minor minister (and current town mayor) by his assistant, Drewnowski. Maciek asks Andrzej where he gets his information and Andrezj tells him through Drewnowski the mayor's secretary. "So he works for both sides? I dispise that," says Maciek.

Maciek is attracted to the attractive barmaid that is hosting the banquet party. "Very nice bar, isn't it Miss?" Maciek asks the bartmaid as he asks her how late she works. Andrzej pulls Maciek away as Maciek says to him, "Like Warshaw girls. Makes me want to stay."

Andrzej decides to make a call at the hotel's payphone while Maciek waits in the hotel lounge reading a paper. Andrezj lies to his source (the mayor named Florian) and says, "I wanted to inform you that the matter's been taken care of. No complications." As Andrzej explains to the mayor about the job, Szcezuka enters the hotel, as he has current reservations from the Town Committee. Maciek is stunned and signals Andrzej that their target has just entered the building. Andrzej then comes clean to the mayor that their job has not yet been carried out, and the mayor orders Andrzej to come to his room immediately.

After Szczuka receives his reserved hotel room, Maciek manages to sweet talk himself into the room next to Szczuka by reminiscing with the hotel porter, who is also a fellow Warsaw native. The two chat about such things as the older section of town and the chestnut trees which were lost when the Germans destroyed most of the city in the aftermath of the Warsaw Uprising. "You deserve it. We Warsovians have to stick together," the porter says to Maciek giving him the room next to Szczuka.

While undressing in his hotel room Maciek can overhear a weeping woman across the hall who knew one of the victims of the cement workers as she proclaims, "The bastards shot him! They apparently meant to kill someone else. Those two died by mistake."

Andrezej heads to see the mayor and upon entering his room Andrzej informs him of the tragic mistake of him and Maciek killing the two cement workers, and the mayor suggests that it's a problem which needs to be immediately corrected. The mayor asks Andrzej when he first joined the resisteance and Andrzej says the year 1941. The mayor then asks him what he fight for, and if it was for the freedom of Poland saying, "Is the Poland you imagined? Lietenant, you must be aware that the only option left to you in a Poland such as this is to fight." Andrzej asks the Mayor if it is necessarary to kill Szczuka, and the Mayor says to him, "An intellectual, an engineer, a communist, and an excellent organizer. A man who knows what he wants. He's just come back from Russian after several years away, and now he's been named to the Party's Regional Committee. You're surely aware of the power he'll have as first secretary. The skillful removal of such a man should make a favorable impression. It would resonate at the level of both politics and propaganda. Particularly now that the situation in our sector just became much more complicated. I just recieved a report that Captain Wilk's detachment was surrounded by the army and security police last night. They suffered heavy losses. Unfortunately the Captain was killed."

Szczuka has recently returned from abroad (he served during the Spanish Civil War like many communists in the 1930s, and also spent time in the Soviet Union while the Germans occupied Poland), and is attempting to locate his son Marek. Szczuka's wife had died in a German concentration camp, and Marek had been staying with an aunt. Szczuka did not approve of the aunt's right-wing political views, and had written to her telling her to send his son Marek to live with other people he knew, apparently people whose political views were closer to Szczuka's own, but the aunt continued to raise Marek, who adopted her right-wing views and joined the Home Army (serving under an officer that Andrzej will replace later in the film).

Szczuka goes to visit the aunt named Katarzyna, (who seems to be the Mayor's wife), to find out where his son is, but she says that he is already a grown man at 17 and that she does not know. Szczuka asks her what kind of man did she raise him to be and she says, "A good Pole, I can assure you." Before he leaves he angrily says, "I can imagine with your type of patrotism. It's not at all hard to guess what kind of man you raised my son to be. But too bad. What's done is done. But he's only 17. And I assure you that if he's alive, sooner or later he'll be my son again." Right when Szczuka turns to leave the mayor escorts Andrzej out. The mayor notices Szczuka leaving and his wife says to the mayor, "It was nothing important." Andrzej is then escorted out by the mayor with all three character's barely missing each other by seconds.

Andrzej arrives back down to the bar to tell Maciek that the job is still on and Maciek tells him that he has the room next to Szcezuka. In one of the great moments of the film, the two comrades light several glasses of vodka which suggest votive candles, in memorial to their fallen colleagues as they listen to a famous soldier's song titled "Czerwone maki" about the battle of Monte Cassino of May 1944.

The two discuss their difference in age and yet their similar devotion to their cause over the last few years during the war and Andrzej says, "We knew what we wanted. And what they wanted of us." Maciek says, "They wanted our lives, and they still do!" Maciek is then how he will handle Szczuka and Maciek says, "Don't worry. I'll manage." Andrzej says that he is his responsibility to Florian, and Maciek says he is responsible for him. "Everybody's gotta be responsible for somebody." Andrzej tells Maciek that Florian doesn't want him directly involved on the job and he has to leave immedietly that morning to take Wilk's place, which is why Maciek has precious little time to take care of Szczuka.

Throughout the night Drewnowski becomes giddy at the thought at what his boss' promotion will do for his own career, drinking with a cynical reporter until he is quite drunk. Meanwhile Maciek's crush on Krystyna grows as the hour he must assassinate Szczuka nears, and before leaving to his room Maciek asks Krystyna the barmaid to meet him after she is done with her job, at his room 17, at 10:30, and tells her he'll be waiting.

Maciek is quite surprised when Krystyna comes to his room (interrupting him while he is putting the pieces of his handgun) and when she is welcomed in she says, "Do you want to know why I came? Its simple. I could never fall in love with you." He eventually tells her, "You know, I wasn't sure you'd come."

Throughout the evening the two lovers made love as Maciek says to Krystyna,"You know what just occured to me? We me just a few hours ago, but I feel like we've known each other much longer." She asks him why he always wears those dark sunglasses and Maciek says, "A souvenir of unrequited love for my homeland. It's nothing, really. I spent too much time in the sewers during the uprising. Maciek suddenly hears Szczuka returning to his room next door while Andrezej arrives to Maciek's room, but decides not to knock when hearing Maciek has a female guest. Maciek and Krystyna decide to go for a walk and in a brilliant shot the two end up in a bombed-out church as an image of Christ crucified upside down hangs between the two of them.

Krystyna reads an inscription which is a poem by Cyprian Norwid: "So often are you as a blazing torch with flakes of burning hemp falling about you. Flaming, you know not if flames freedom bring or death, consuming all that you most cherish. Will only ashes remian, and chaos, whirling into the void..." It's too blurred to read the rest but Maciek finishes it by saying: "Or will the ashes hold the glory of a star-like diamond, the Morning Star of everlasting triumph." Maciek tells Krystyna how he'd like to make some serious changes in his life saying, "Until now I haven't thought about many things. Life always managed to work itself out somehow, and the point was simply to survive. I just want a normal life, to take up my studies. I graduated from High school. Maybe I could go to the technical institute. God, if I had known yesterday what I know now...until now, I didn't know what love was. I really didn't. When Krystyna breaks her heel Maciek attempts to fix by accidently stumbling into a crypt where the bodies of the men he killed that morning are laid out awaiting burial. A elderly man yells for the two youngsters to leave saying, "This is how young people act these days! They can't even respect the dead. You act all happy, while two people murdered today lie there next to you."

Maciek escorts Krystyna back to the hotel, where she has to go back to work at the bar until it closes at 3:00 a.m. Before heading inside Maciek promises he can change his current plans and stay there with Krystyna. When she returns to work Maciek runs into Andrzej, (who he was initially trying to avoid.) Maciek says to Andrzej:

"Listen, I need to talk to you, seriously. You know I'm not a coward. Try to understand, Andrzej. I can't go on killing and hiding. I just wanna live. You gotta understand."

"Are you speaking as a soldier or a friend? I can only speak to you on this matter as your superior officer. You took this on yourself. Nobody forced you. You fell in love. That's your business. But to put your personal affairs before our cause...you know what they call that."

"I have never been a deserter. Don't you understand people can change? I'm not running away!"

"You want me to say: Fine. You're in love. Do as you like. How many times have we been in action together? What if you had fallen in love then? Would you have come to me then? How about during the uprising. You keep forgeting your one of us. And that's what counts."

"Do you believe in all of this."

"That's of no importance."

Maciek is taken aback at first, but understands and decides he must carry out his orders and agrees to Andrzej early the next morning like originally planned. Meanwhile Drewnowski becomes quite drunk, and barges into the banquet dinner. In short order he sprays the guests with a fire extinguisher, pulls the tablecloth (and everything on it) to the floor and finds himself out of a job which the Mayor's associates say, "Now you've done it. You can say good-bye to your career. You'll be singing a different tune tomorow. The minister will ruin you."

Meanwhile, Szczuka is awakened and informed from the local security official that his son Marek (who is part of Wilk's group) has been captured by the Red Army and is being held in detention. When his son is asked his age Marek proudly says, "A hundred and one." Szczuka is told that a car is waiting for him out front, and as he is about to leave the hotel, Maciek hides under the staircase of the hotel waiting for Szczuka to leave. Maciek is held up for a minute by the friendly porter, but eventually catches up to Szczuka (even if at the last minute Maciek paces up and down before the hotel, his mind racing over whether or not to kill his targe. Maciek eventually shoots Szezuka before Szczuka reaches the awaiting car, as he collapses dead in Maciek's arms while fireworks begin to go off celebrating the end of the war.

After the party dies down and everyone heads off to their separate rooms for sleep Maciek arrives at the bar to tell Krystyna that he won't be able to change things as originally planned, and Krystyna angrily tells Maciek to just leave. Before leaving the hotel porter says to Maciek "If we could only celebrate a Warsaw not in ruins."

After the party dies down and everyone heads off to their separate rooms for sleep Maciek arrives at the bar to tell Krystyna that he won't be able to change things as originally planned, and Krystyna angrily tells Maciek to just leave. Before leaving the hotel porter says to Maciek "If we could only celebrate a Warsaw not in ruins."

The following morning, Maciek goes to the truck where Andrzej awaits. From concealment he watches as Drewnowski arrives thinking he will join them, but Andrzej is aware that Drewnowski is only doing it because he has no other choice. Andrzej throws Drewnowski to the ground and drives off. When Drewnowski sees Maciek, he calls out to him and Maciek flees and accidently runs into a patrol of Polish soldiers.

He is shot and ends up running through several clotheslines of sheets bleeding to death, eventually dying in a trash heap.

ANALYZE

Ashes and Diamonds has rightly been lauded as one of the finest of postwar East-Central European films, and the most vital work of the Polish School. It is salutary, however, to remember how much controversy has dogged the film within Poland itself, and that this is more than a matter of regime-led misgivings about a work with potentially subversive accents. It stems from the film’s pursuit of conflicting goals: to deal with the Polish Home Army’s resistance against the incoming, Soviet-backed Communist regime and yet satisfy both the Polish populace who held that army dear and a Communist party that wielded powers of censorship, even though it had renounced a Stalinist rigor of repression. Criticize the Home Army too strongly and the audience will turn on you; offend the regime, and your film might be amputated or aborted. (Wajda himself reports efforts to remove Maciek’s death scene going right down to the wire of the first screening.)

This tightrope balance had been central to the Jerzy Andrzejewski novel upon which Wajda’s film was based. It is worth reflecting, therefore, on why more Poles took Wajda’s film to heart than had embraced Andrzejewski’s novel. Did visuals offer more leeway for an ambiguity that could fool the censors, as Wajda himself has argued? Was Zbigniew Cybulski’s electrifying performance the key factor? Or was it Wajda’s transformation of Cybulski’s role into the undisputed focal point of the ironic tragedy whose twenty-four-hour period was the hinge connecting the end of one (world) war to the start of a new (civil) one? Perhaps the distinguished novelist Maria Dabrowska was right to say at the time that it told as much of the truth as could be told in the circumstances. Such praise may suggest a work partially tainted at source, and Wajda himself appears to endorse this view in his post-1989 The Ring with a Crowned Eagle (1993), a corrective echo of the earlier endeavor.

Filming in 1958, Wajda was, of course, working in the aftermath of the liberalizing 1956 “thaw,” otherwise known as “the Polish October.” But there were limits to the freedom it brought, and the very recent nature of that change, combined with the artist’s canny awareness of the possibility of a renewed freeze, make it hardly surprising that both the film’s opening and its ending—in which the charismatic Maciek stumbles to his death on a rubbish dump, curling up unglamorously in a fetal position, legs twitching as if to kick death away—should be so compatible with the state’s denunciation of the Home Army.

That opening shows Maciek and his companion Andrzej lounging in the grass, but the camera’s slide down from a chapel’s cross suggests a fallen world. That suggestion will be spelled out graphically later in the film, when Maciek enters a ruined church with his one-night lover, Krystyna, and an image of Christ crucified hangs upside down between them. Shortly thereafter, the camera will slide down again from Maciek to the corpses of the men he killed earlier, recalling the time before he was a sympathetic figure. As he and Andrzej attempt the assassination of a newly installed local party secretary, Szczuka, they catch the wrong men, and Maciek’s tommy-gun eliminates one at the chapel’s door. The fire his bullets ignite on the man’s back is the infernal result of his teeth-baring ferocity, and the opening appears calculated to compromise him both with the Communists whose representative he is seeking to kill and with Polish patriots shocked by his sacriligeous indifference to the presence of the chapel. Yet even here he is an uncomfortably real figure, disturbed by the ants—just one of the Buñuelian elements of this sequence—crawling across the gun he had laid aside in the grass, not a simple stereotype of the assassin as reactionary Other. In retrospect, moreover, any inhumanity in him can be read as the imprint of the war that is all he has ever known and that has damaged his perspective as well as his sight.

The sign of that damaged vision is found in the dark glasses that do double duty as a realistic image of the effects of wandering in the sewers as a Warsaw Uprising insurgent (here Wajda evokes his previous film, Kanal) and as the symbol of late-fifties existential cool. Maciek has one foot in the existentialism of resistance, another in the existentialism of fashion. Zbigniew Cybulski, who plays the part, was often called Poland’s James Dean, though his fused toughness and boyishness seem to make him both its Dean and its Brando. Cybulski’s performance electrified Wajda, who described it as the film’s uncensorable essence. The film’s careful architecture builds parallels between Maciek’s damage by the struggle and that of Szczuka, who becomes the father he cannot have and who himself has lost his son, Marek, brought up to fight with the other side and caught fighting with the partisans. It is the urgency of Szczuka’s desire to see his son that causes his death, prompting him to walk before the arrival of the car ordered to take him to Marek. Instead, he meets the son’s Oedipal double, the one willing and able to kill him. Maciek and Andrzej may be given the film’s best-known scene, in which they light glasses of vodka, suggesting votive candles, to their fallen colleagues, but Szczuka is allowed a similar reminiscence of Spanish Civil War comrades—and nostalgic political songs accompany both scenes. The question of whether the balance is merely apparent, its even-handedness a smokescreen for stronger allegiance to Maciek, goes to the heart both of the work and the controversy around it, as it can be argued that we are not so much with Maciek as with Cybulski, and simply because of the greater power of his performance.

Having failed to assassinate Szczuka at the beginning, Maciek is ordered to complete the job. The chance that frustrated him once threatens to do so again when he meets the barmaid Krystyna and what both had intended as a one-night stand opens vistas to a possible peaceful future—to dreams of study, normality. But army discipline requires a fulfillment of orders, and he kills Szczuka in the dark, though even at the last minute he paces up and down before the hotel, his mind racing over whether or not to follow his target. As his victim falls dead in his arms, the embrace is an ironic image of the impossibility of unity within Poland and between the generations. And as the fireworks rising above them illuminate a scene that shows there is nothing to celebrate, in another irony, no one perceives the flashlit crime. As in tragedy, the death within the family gives the lie to the idea of a national family, to the hotel porter’s hanging out of the national flag.

If, for all its tragedy and multiple ironies, the film exhilarates, it is through the power of its artistry and because the authority of its synthetic image of the postwar Polish dilemma does indeed tell as much of the truth as could be told—as Dabrowska had said. The artistry is not confined to Cybulski’s performance or Wajda’s compression of Andrzejewski’s more leisurely novel and list of dramatic personae into a tightly knit, twenty-four-hour confrontation. It is also continually present in the deep focus of cameraman Jerzy Wojcik, which both underscores the ironies and evokes the oppressiveness of a history with whose cruelty Poles had become all too well acquainted. Characters are betrayed by what they cannot see—as when the foregrounded Andrzej telephones the major to report mission accomplished as Szczuka enters the hotel lobby in the background—while the ever-visible ceilings above the characters’ heads embody the limits on their actions, the fact that something always bears down upon them and constrains them.

The film’s taut, packed, slightly fevered air flows to a large extent from a doubling that affects both imagery and characterization. Much of the imagistic irony derives from the title, whose source and import are given when Maciek and Krystyna visit a church and Krystyna partly deciphers an inscription in which nineteenth-century poet Cyprian Norwid asks whether the remains of chaos will be ashes or a diamond. Fire bursts from the back of the man Maciek guns down at the chapel door; Maciek lights the glasses of vodka, as well as Szczuka’s cigarette; and just after he has shot at Szczuka, fireworks light up the sky. Doubled imagery links Maciek and Drewnowski, both associated with the white horse that represents Poland. Thus, although these characters appear opposed, with Maciek denouncing Drewnowski’s careerist double game, this linkage suggests both greater complexity and Wajda’s possible own partial (merely tactical?) underwriting of the official view of the Home Army underground. After all, there are further links: Drewnowski’s fire extinguisher spraying the Monopol banquet guests echoes and parodies Maciek’s initial killing; the two actors—Cybulski and Bogumil Kobiela—had been co-conspirators in the Bim-Bom student cabaret. Tellingly, Maciek is running away from Drewnowski’s call when he bumps into the soldiers, carries on running, and is shot.

This particular doubling underlines the complexity in Wajda’s position, which is also a dilemma. So if he boils down Andrzejewski’s novel into a tragedy with an Aristotelean unity of time, place, and action, it is also one that corresponds to a Hegelian model of tragedy that may be seen as standing Marxism on its head: in that model, of course, tragedy is precipitated not by any flaw within a character but by the collision of two figures, each of whom advocates a one-sided good. Tragedy becomes a matter of situation, not character. After all, in Szczuka communism achieves a nobility that critiques the pettiness of the film’s prewar nobility, bent only on survival and self-aggrandizement. The rift between opposed goods then bifurcates Maciek, who desires both normality and love and obedience to army discipline. The conflict is one between the claims of brotherhood in arms and an individual desire that includes the sexual (Krystyna’s naked back is quite daring for both period and place). But the rift seems also to run through Wajda himself, who echoes the Communist authorities’ derision of the prewar order of the older generation (“the democratic press” is represented by the drunken Pieniazek) but also sees the new era in the same terms as Pieniazek: as one in which the scum comes to the top. By the end, the most positive figure in the new order is dead, and—as if the embrace in death had pulled him deathward, too—Maciek loses both his chance at a new life and then life itself. The possibility of national rebirth is mocked by the fetal kicking of his death spasm on the rubbish dump and by the parallel scene of the hotel revellers’ hypnotic drift at dawn, a restaging of the paralysis besetting would-be rebels at the end of Stanislaw Wyspianski’s fin-de-siècle play The Wedding. There are only ashes, no diamonds.

-Paul Coates

The fascinating creation of the character of Maciek Chelmick played by actor Zbyszek Cybulski with his dark glasses and smooth exterior, completely took European audiences by storm. Maciek blends the existentialism of the gritty resistance, and the existentialism of fashion and coolness; as which he was often called Poland's James Dean, portraying a toughness and boyish vulnerability, which seemed to tackle an essence of both James Dean and Marlon Brando.

In the interview accompanying the 2010 Criterion box-set release of Wajda’s war trilogy, of which Ashes and Diamonds is the concluding part, director Andrzej Wajda says that he asked Zbyszek Cybulski if he’d seen films with James Dean. Cybulski, who had recently been in Paris, told Wajda that he was familiar with Dean and they agreed that his style was worth developing in the film. Like Dean, Cybulski died young (in a railway accident that was strangely anticipated in the opening scene of the first film in Wajda’s war trilogy - A Generation.

Wajda also cites the impact on Ashes and Diamonds of American cinema and of Orson Welles Citizen Kane in particular. When comparing scenes and themes, however, the film that was clearly most influential on Ashes and Diamonds is The Wild One directed by László Benedek, and featuring a young Marlon Brando. While the primary theme of Ashes and Diamonds follows the eponymous post-war book by Jerzy Andrzejewski, the relationship between Maciek and the barmaid Krystyna is loosely based on that between Johnny (Marlon Brando) and Kathie (Maria Murphy), the barmaid in the small town that his gang rides into.

In both cases sudden emotional involvement makes the male protagonists reassess their prior commitments: in Maciek’s case to armed resistance as the Soviet army entered Poland; in Brando’s case to his rebellious bike gang. Wajda references two notable scenes from The Wild One: Johnny’s interaction with the barmaid Kathie, while paying for a beer and toying with the change, is echoed by Maciek’s similar scene when barmaid Krystyna is trying to pour him a vodka; Johnny and Kathie jiving in the small town bar is mirrored by Maciek and Krystyna waltzing round the Monopol hotel bar. In both films there is a classic unity of time, place and action. Wajda says he deliberately asked Andrzejewski to compress the plot of his book into a single day for the screenplay.

The main character Maciek, has to wear sunglasses all the time, since he was in the Warsaw Uprising, (which was referenced in director Andrzej Wajda's earlier war film Kanal), which took place between August 1 and October 2 (63 days in total) and where insurgents used the Warsaw sewers to move between the Old Town and Downtown Warsaw. Maciek being part of the uprising explains his hatred of the Soviets, who were on the other side of the Vistula but did not help the insurgents at all. He also mentions Warsaw as a beautiful memory to the porter, obviously referring to the almost total (85%) destruction of Warsaw by the Germans following the uprising. Much of the irony of the film is derived from the title of the film, especially the sequence in which Maciek and Krystyna visit a church and Krystyna partly deciphers an inscription in which a nineteenth-century poet Cyprian Norwid asks whether the remains of chaos will be ashes or a diamond.

There are several parallel's and doubling within Ashes and Diamonds careful architectural structure of its story. There is the tragic repurcussions of the war which negatively effect both Maciek and Szczuka. For Maciek, his devotion to his political ideologies will ultimately prevent Maciek from ever having any long lasting romance or happiness in his future. Szczuka's devotion led his relationship with his son to be forever tarnished, as his son Marek has been brought up to fight on the opposing side with the partisans. It is the urgency of Szczuka's desire to want to reunite with his son that causes him to be vunerablly out in the open, unguarded, which will lead to his assassination. I've always felt that Maciek was in a way the symbol of the son that Szczuka never had, as Maciek and Marek are greatly similar by name, age, and probably had the same drives and naive motivations when first joining the particians. And so it makes perfect sense that the fates of Szczuka and Maciek will ultimately collide with one another near the end of the film, both of their lives tragically taken by violence. They're the mirrored parallels of the symbolic nature of fire, in the beginning sequence of the tommy-gun bullets which ignite the fire on the victims back, and later in the classic vodka glasses sequence, which were lit to suggest votive candles for an memorial to Maciek and Andrzej's dying comrades.

This memorial sequence is also later paralled with Szczuka reminiscing on his fallen Spanish civil War comrades, as political songs accompany both memorial sequences. After Maciek goes through with the killing of Szczuka in the dark early dawn of the morning, his victim falls dead in his arms similar to an embrace, just as fire reoccurs once again with the sudden fireworks which begin to go off, celebrating the end of the war, which can be looked at as a ironic image of the impossibility of unity with Poland and between the generations. When the fireworks are rising, it illumnates a scene that shows that there is nothing really to celebrate, as in tragedy the death within the family gives the lie to the idea of a national family; to the hotel porter's hanging out of the national flag. Doubled imagery links can also be made between Maciek and the cowardly character of Drewnowski, both associated with the white horse that represents Poland, and yet Maciek denounces Drewnowski's careerist double game. Drewnowski's fire extinguisher spraying mirrors Maciek's initial killing in the beginning of the film, and at the end Maciek running from Drewnowki's call is what gets Maciek to accidently bump into the soldiers who ultimately shoot and kill Maciek.

It seems to be a very small world that these character's inhabit in Ashes and Diamonds, where everybody seems to know everybody, liasions are easily made and just as easily broken, and character's simply betray, manipulate, and deceit one another, as long as it fulfills either some form of political ideology that they feel obliged to be dedicated or obedient to, or if its used simply for personal gain. (In a slightly ironic scene is a sequence where Andrzej is informing to his superior over a hotel payphone that the job of assassinating his client was perfectly taken care of, all the while the client who unfortunately is still presently alive, coincidentally makes his way into the hotel lobby within the background of the shot.) Irony and tragedy directly come clashing into one another at the end of the film, as Maciek unfortunately loses a chance at a brand new life and new found happiness, as he finds himself tragically caught in the middle violence. Maciek's tragic fate is something that commonly occurred to the flawed, venerable anti-heroes within the American world of the noir, as its pessimistic ending brings back the ironic poem written by Cyprian Norwid, which was read out-loud by the films lovers earlier in the film: "So often are you as a blazing torch with flakes of burning hemp falling about you. Flaming, you know not if flames freedom bring or death, consuming all that you most cherish. Will only ashes remain, and chaos, whirling into the void. Or will the ashes hold the glory of a star-like diamond, the Morning Star of everlasting triumph..."

It seems to be a very small world that these character's inhabit in Ashes and Diamonds, where everybody seems to know everybody, liasions are easily made and just as easily broken, and character's simply betray, manipulate, and deceit one another, as long as it fulfills either some form of political ideology that they feel obliged to be dedicated or obedient to, or if its used simply for personal gain. (In a slightly ironic scene is a sequence where Andrzej is informing to his superior over a hotel payphone that the job of assassinating his client was perfectly taken care of, all the while the client who unfortunately is still presently alive, coincidentally makes his way into the hotel lobby within the background of the shot.) Irony and tragedy directly come clashing into one another at the end of the film, as Maciek unfortunately loses a chance at a brand new life and new found happiness, as he finds himself tragically caught in the middle violence. Maciek's tragic fate is something that commonly occurred to the flawed, venerable anti-heroes within the American world of the noir, as its pessimistic ending brings back the ironic poem written by Cyprian Norwid, which was read out-loud by the films lovers earlier in the film: "So often are you as a blazing torch with flakes of burning hemp falling about you. Flaming, you know not if flames freedom bring or death, consuming all that you most cherish. Will only ashes remain, and chaos, whirling into the void. Or will the ashes hold the glory of a star-like diamond, the Morning Star of everlasting triumph..."