Weekend (1967)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Weekend Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Jean-Luc Godard’s cathartically political and infuriating masterpiece Weekend is one of the key films of the late 1960’s. It is on one hand a chaotically brilliant black comedy and on the other hand a surrealistically acid disdain on the nihilistic bourgeoisie consumer society. Weekend is less like a film and more like a abstract angry political collage, as its pop art color scheme and its two-dimensional lover’s go on a surreal cross-country road trip which descents down a fantastical rabbit hole of utter hell. A married couple named Corinne and Roland, are plotting each other’s demise with their respective lovers, while at the same time both planning to head out by car for Corinne’s parents’ home in the country to secure their inheritance from Corinne’s dying father by murdering him; maybe her mother as well if she refuses to split the inheritance. In one of the iconic sequences of the film the perpetually bickering couple bully themselves through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross-section of the bourgeoisie middle class, as one long take shows a debris field of wrecked and burning vehicles, dead corpses, and repeated honking horns. It is a very long traffic jam, as this one long take continues without interruption for perhaps three-quarters of a mile. [fsbProduct product_id=’838′ size=’200′ align=’right’]”Politics is a traveling shot,” Godard told critics as the road unleashes the two protagonists inner beastliness and primitive instincts, as they route through a hellish landscape of predatory unconscious that resembles a projection of political violence and angry ideology, allusions to ideas and high-culture, free-ranging historical personalities and characters from literature, and philosophical garbage collectors and cannibal freedom-fighters; all the while the two of them slowly approach the collapse and destruction of Western civilization. Godard repeatedly fractures the narrative with flash cuts and inter-titles while he greatly tests the patience of his audience with such fascinating sequences of a barnyard recital of Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 18, as the camera makes a complete 360-degree rotation, as we see the entire barnyard pianist, listeners, passersby, and the camera crew three times in one sequence. And a haunting detailed sexual exposition in which Corinne’s lover assumes the role of psychiatrist while Corinne sits on a desk in her bra and panties and describes a recent three-way episode with a different lover and his girlfriend involving eggs and a bowl of milk; which is obviously a direct parody of Bibi Andersson’s emotionally overwrought ‘orgy monologue’ in Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece Persona.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Weekend Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Jean-Luc Godard’s cathartically political and infuriating masterpiece Weekend is one of the key films of the late 1960’s. It is on one hand a chaotically brilliant black comedy and on the other hand a surrealistically acid disdain on the nihilistic bourgeoisie consumer society. Weekend is less like a film and more like a abstract angry political collage, as its pop art color scheme and its two-dimensional lover’s go on a surreal cross-country road trip which descents down a fantastical rabbit hole of utter hell. A married couple named Corinne and Roland, are plotting each other’s demise with their respective lovers, while at the same time both planning to head out by car for Corinne’s parents’ home in the country to secure their inheritance from Corinne’s dying father by murdering him; maybe her mother as well if she refuses to split the inheritance. In one of the iconic sequences of the film the perpetually bickering couple bully themselves through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross-section of the bourgeoisie middle class, as one long take shows a debris field of wrecked and burning vehicles, dead corpses, and repeated honking horns. It is a very long traffic jam, as this one long take continues without interruption for perhaps three-quarters of a mile. [fsbProduct product_id=’838′ size=’200′ align=’right’]”Politics is a traveling shot,” Godard told critics as the road unleashes the two protagonists inner beastliness and primitive instincts, as they route through a hellish landscape of predatory unconscious that resembles a projection of political violence and angry ideology, allusions to ideas and high-culture, free-ranging historical personalities and characters from literature, and philosophical garbage collectors and cannibal freedom-fighters; all the while the two of them slowly approach the collapse and destruction of Western civilization. Godard repeatedly fractures the narrative with flash cuts and inter-titles while he greatly tests the patience of his audience with such fascinating sequences of a barnyard recital of Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 18, as the camera makes a complete 360-degree rotation, as we see the entire barnyard pianist, listeners, passersby, and the camera crew three times in one sequence. And a haunting detailed sexual exposition in which Corinne’s lover assumes the role of psychiatrist while Corinne sits on a desk in her bra and panties and describes a recent three-way episode with a different lover and his girlfriend involving eggs and a bowl of milk; which is obviously a direct parody of Bibi Andersson’s emotionally overwrought ‘orgy monologue’ in Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece Persona.

PLOT/NOTES

A FILM ADRIFT IN THE COSMOS

A married couple named Corinne and Roland are both planning each other’s demise with their respective lovers. Corinne is with her lover. “When Roland drives your father home from the clinic, it would be nice if they both died in an accident,” says Corinne’s lover.

A FILM FOUND IN A DUMP

The lover asks if Roland got his brakes repaired yet and Corinne says she managed to maker her husband forget. The lover wonders if Roland is getting suspicious and Corinne says, “No. I let him screw me sometimes, so he thinks I love him.” While the two talk on the porch they watch a guy get beaten to death in the street because the guy broke the other person’s headlight. Roland gets a call from his lover and he explains the fight he saw in the street saying, “I though he was dead for a moment. Yes, it would have been nice if it was her. No, the money first. I’ve got to be careful, after the sleeping pill and gas. The main thing is for her dad to pop off. When Corrinn’s got the money we’ll take care of her.. Your my splendid bitch, you know that.”

ANAYLSIS

Corinne’s lover assumes the role of a psychiatrist, sitting at a desk in a darkened office while Corinne sits on the desk in her bra and panties and describes a three-way with a different lover and his girlfriend. An orgy, involving eggs and a bowl of milk, loosely borrowed from Bataille’s Histoire de l’oeil.

10:00 a.m.

Corinne and Roland are about to head out by car for Corinne’s parents’ home in the country, plotting to secure their inheritance from Corinne’s dying father, by murdering him; maybe her mother as well if she refuses to split the inheritance.

SCENE OF PARISIAN LIFE

But before leaving Roland accidentally hit another car’s bumper when a young mischievous child distracts Roland. “They’ve damaged the Dauphine!” The owner of the hit Dauphine comes out and starts to throw a fit, violent attacking Roland with a tennis racket and insect spray. Roland and Corinne escape just before the owner’s husband runs out with a gun and fires at them.

11:00 a.m.

SATURDAY

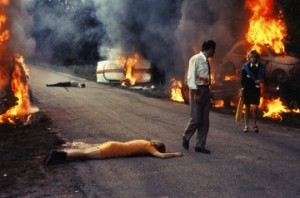

Corinne and Roland bully themselves through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross-section of the French middle class, as one long take shows a debris field of empty buses, wrecked and burning cars, dead corpses, and repeated honking horns. It is a very long traffic jam, and the protagonists pull out into the other lane to pass it, as this one long continues take continues without interruption for perhaps three-quarters of a mile. After getting through the traffic jam Corinne and Roland park so Corrine can call her mother and inform her that the highway was blocked and that she will be late. Corinne says to Roland before phoning, “We must pick up Father from the clinic. Mother mustn’t arrange it. If Papa dictates a new will into his tape recorder…Then why have we put poison in his grub every Sat for five years? See what happened to that Triumph? If only it were Papa and Mama.”

THE CLASS STRUGGLE

Godard presents several still images of deceased accident victims and profile shots of regular townspeople standing among billboard consumer ads. A hysterical woman wearing green seems to insult a man driving a large green tractor who killed another young man in his vehicle. “Without me and my tractor the French would starve” the man tells her. The woman shouts, “He had the right. He was handsome, young, rich. He had the right over fat once, poor ones, old ones.”

PHONY

GRAPH

Corinne and Roland drive off as the tractor man asks for help yelling, “We’re all brothers, as Marx said.” While Corinne and Roland bicker on the road, Corinne says, “Didn’t you hear what he said? ‘We’re all brothers, as Marx said.” Roland says it wasn’t Marx who said that, “Another communist said it. Jesus said it.”

SATURDAY

3:00/4:00

The two lovers fight off barbaric people as Roland can’t believe this behavior as this isn’t the Middle Ages.

THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL

The two are carjacked by a strange-looking man named Joesph Balsam with a gun and woman who looks like a mime. During the drive the Corinne and Roland try calling out for help, as Joesph fires his gun to quite them. Joesph says Corinne and Roland have a Readers Digest Look and explains who he is saying: “I’m here to inform these Modern Times of the Grammatical Era’s end and the beginning of Flaboyance, especially in cinema.” Joesph says he is a magician and if they take him to London he will grant them anything they wish. (He proves it by having Corinne pull a rabbit from under the dashboard of the car.) Joesph chases the two lovers out of the car, and into a sheep meadow. Eventually the two make their way back on the road and drive a man on his bicycle off the road created a fiery accident between several vehicles on the road.

FROM THE FRENCH REVOLUTION TO GAULLIST WEEKEND

Saint-Just (Jean-Pierre Léaud) makes a political speech of the French Revolution while Corinne and Roland make their way on foot through the landscape. “From French Revolutions to Gaullist weekends, freedom is violence.”

SUNDAY STORY FOR MONDAY

Saint-Just is using the payphone (he seems to be babbling through song) and Corinne and Roland need to eagerly use it. Roland asks if Saint-Just can take the two of them to the nearest garage. Saint-Just only wants to take Corinne. Corinne and Roland make their way through a desolated road of death and destruction, which corpses and burning vehicles littered everywhere.

LEWIS CAROL’S WAY

While looking for the town of Oinville, Corinne and Roland come across two characters of literary fact and fiction: Tom Thumb from Mother Goose and Emily Bronte author of Wuthering Heights. Both are refracted through the lens of Louise Carroll. Roland says, “What a rotten film, all we meet are crazy people.” Tom Thumb is quoting a Hollywood poem while Emily Bronte picks up a pebble and gives her perception on what a pebble can mean. Corinne says, “This isn’t a novel, it’s a film. A film is life.” Roland lights Emily Bronte’s skirt on fire and Corinne says, “We have no right to burn even a philosopher.” Roland says, “Can’t you see they’re only imaginary characters?” Corinne asks why she is crying than and Roland says “No idea.” Emily Bronte is then burned alive.

A TUESDAY IN THE 100 YEARS WAR

Corinne and Roland hitch a ride with a driver who needs help with his concert, because his helper ran off.

MUSICAL ACTION A grand piano is set up in a barnyard, and the pianist begins to play a recital of Mozart’s Sonata 18. In a startling shot, Godard places his camera in the center of the barnyard and moves it through three complete 360-degree revolutions. We see the entire barnyard pianist, listeners, passersby, the camera crew three times in sequence.

A WEEK OF 4 THURSDAYS They’re the Italian actors in the co production. While Corinne and Roland are trying to hitch a ride a car stops and the driver asks Roland if he is in a film or in reality. Roland says, “In a film.” The driver says, “In a film? You lie too much”, and drives off. Another car pulls up and asks Roland if he would rather be screwed by Mao or Johnson. Roland says Johnson of course but the decide to drive on calling Roland a fascist. Corinne and Roland finally get a ride on a garbage truck.

No need to be nasty The camera stops dead in its tracks while two garbage men are eating sandwiches. The two garbage men deliver a protracted and long voice-over monologue about colonialism and exploitation.

LIFE

Corinne and Roland eventually arrive at her parents’ place, only to find that her father has died and her mother is refusing them a share of the spoils. They kill her and place her body in her vehicle, and burn the vehicle. (next to a crashed plane). Corinne and Roland set off on the road again with a newfound spark of love for one another and head to Versailles.

SEINE-ET-OISE LIBERATION FRONT

The two lovers fall into the hands of a group of hippie revolutionaries identified as the Seinet-Oise Liberation Front (FLSO) supporting themselves through theft and cannibalism. The group (which reunites the woman in green and Joesph Balsam) drag Corinne and Roland to their camp which is located deep within the wilderness as their tribal broadcasts cinematic code names: “This is The Searchers. I hear you, Battleship Potemkin. Johnny Guitar. Over.”

AUGUST LIGHT

The tribe kill and disembowel Roland as they state: “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome with more horror.”

SEPTEMBER MASSACRE

A pig is horrifically slaughtered on camera while a drummer plays the drums. Later the FLSO have a tribal war with one another and many are shot and killed. After the FLSO has cooked Roland, the FLSO feed him to Corinne.

THE END

ANALYZE

Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) is a key film of the late sixties, a premonition of the political explosion of May ’68 and its chaotic aftermath, a comedy of brilliant set pieces that cumulatively stage the collapse of Western civilization. Its acid depiction of consumer society and the middle class is exemplary of a complex, multilayered cinema of ideas that flourished in the sixties and seventies in the films of Godard, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alexander Kluge, Luis Bun?uel, Robert Bresson, and many other directors, comparable to literature in artistic ambition and scope. What sets Godard’s film apart is its sheer velocity, its outrageousness, and its exuberant disdain for almost everything.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) is a key film of the late sixties, a premonition of the political explosion of May ’68 and its chaotic aftermath, a comedy of brilliant set pieces that cumulatively stage the collapse of Western civilization. Its acid depiction of consumer society and the middle class is exemplary of a complex, multilayered cinema of ideas that flourished in the sixties and seventies in the films of Godard, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Alexander Kluge, Luis Bun?uel, Robert Bresson, and many other directors, comparable to literature in artistic ambition and scope. What sets Godard’s film apart is its sheer velocity, its outrageousness, and its exuberant disdain for almost everything.

With its pop art color scheme and two-dimensional characters, Weekend is less like a novel than a pamphlet, and more like a fairy tale than either. The presiding trope is Alice’s tumble down the rabbit hole. Weekend opens conventionally enough, like a Chabrol movie or a Balzac novel: a married couple, Corinne (Mireille Darc) and Roland (Jean Yanne), are planning each other’s demise with their respective lovers, and plotting together to help Corinne’s ailing father into the afterlife— maybe her mother as well, if she refuses to split the inheritance. But any illusion of melodramatic realism is quickly punctured in a scene where Corinne’s lover assumes the role of psychiatrist, sitting at a desk in a darkened office while Corinne sits on the desk in her bra and panties and describes a recent three-way with a different lover and his girlfriend, an orgy, involving eggs and a bowl of milk, loosely borrowed from Bataille’s Histoire de l’œil. The episode is a parody of Bibi Andersson’s emotionally overwrought “orgy monologue” in Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, rendered flat and passionless by Corinne’s bored delivery, the camera’s slow zooming in and out in near darkness on the barely distinguishable figures, and swelling, “ominous” B-movie theme music that occasionally drowns out her voice. Godard establishes here an atmosphere of neurotic apprehension and narrative unreliability sustained throughout the rest of the film. “Is this a dream or did it really happen?” “I don’t know.”

All but three brief scenes in Weekend take place out of doors, in meadows and woods, on roadways and farms. The protagonists are removed from their usual urban reality and observed in something like a state of nature, in high relief, where Godard’s camera examines them like insect specimens. En route to Corinne’s family’s house in the countryside, the couple pass through a landscape that resembles a projection of their predatory unconscious. France’s rural heart is depicted as a debris field of wrecked and burning cars, dead bodies, free-ranging historical personalities and characters from literature, philosophical garbage collectors, and marauding revolutionaries.

After bullying their way through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross section of the French middle class, the sullen, perpetually bickering couple proceed with rapacious single-mindedness into a Wonderland that mocks them at every turn. Like a venomous consumer id, obsessed with clothes and cars and cash, they treat every stranger as an obstacle or an opportunity, oblivious to the unlikelihood of encountering Saint-Just in a sheep meadow or Emily Bronte? on a country lane. If the past is there to teach us things, Corinne and Roland aren’t prepared to keep on learning; it takes only a drop of bewilderment or a line of “useless” poetry to unleash their inner beastliness.

For a film whose lead characters are utterly vacuous and driven by primitive instinct, Weekend is overblessed with ideas, allusions to high culture, showstopping longueurs of political theater. The ideas come from Karl Marx and Lewis Carroll, Francis Ponge and Norman O. Brown, MGM and Jacques Lacan—Godard seizes choice fragments from the sixties intellectual zeitgeist and layers them into an abrasive, strangely compelling collage.

The technique of Weekend, however, comes from Brecht. The film excludes any emotional identification with its protagonists. They have no inner lives. Corinne’s only emotional moment occurs when her Herme?s pocketbook is incinerated in a head-on collision. Moreover, she and Roland are conscious of being characters in a movie. Weekend’s fistfights, shootings, stabbings, and highway carnage don’t simulate violence so much as transmit an idea of violence. The bloodshed is so deliberately fake that a scene where a real pig has its throat cut comes as a powerful shock.

Godard repeatedly fractures the narrative with flash cuts and intertitles, and generally tries the audience’s patience with scenes that carry on well beyond any reasonable length—the initial traffic jam, for instance, but also the barnyard recital of Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 18, played partway through and then started again, as the camera three times inscribes a circle around the pianist and his listeners. Most pointedly, a later scene where two garbagemen eat sandwiches while staring into the camera stops everything dead to deliver a protracted theoretical voice-over monologue about colonialism and exploitation. The scene is essential for understanding the overall premise of Weekend, and at the same time so excruciatingly static that critics of the time advised the audience to go out for a coffee as soon as it started.

Weekend is structured like a problem in logic or a mathematical theorem. Virtually every scene reflects the unraveling of Rousseau’s social contract and points to an inevitable disintegration into tribal atavism. Godard, who trained as an ethnologist, adapted the film’s structure from Friedrich Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884). Engels developed his ideas from the anthropologist Lewis Morgan’s study of the Iroquois and Seneca tribes, which posits that, “according to the materialist conception, the determining factor in history is . . . the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life.” Engels describes the emergence of civilization from barbarism, and barbarism from savagery, as marked by stages in the development of articulate speech, the invention of weaponry, and the transition from migratory hunting and gathering to fixed communities based on agriculture.

In Weekend, these stages are set in reverse: a dominant class, alienated from “the production . . . of the immediate essentials of life” and devoted to mindless consumerism, is shown regressing to a state of savagery. Even Morgan’s Indians, alluded to at the outset by a little brat in a headdress, turn up in the form of revolutionary cannibals, declaiming the poetry of Lautre?amont while frying up English tourists.

The film’s internal chronology blurs as it goes along. Social disintegration is charted by red, blue, and white titles that at first display, with excessive frequency, the exact time and day of the passing weekend, or mimic the car’s speedometer, or identify an upcoming scene or a scene already in progress (“The Exterminating Angel,” “Scene of Provincial Life”), but later simply add sardonic commentary with allusive and fragmented phrases (“Totem and Taboo,” “FLSO,” “August Light”), or suggest a greater passage of time than we actually sense passing on-screen, by posting months of the French Revolutionary Calendar (“Thermidor,” “Pluvio?se”)—as if time had mysteriously dilated, or frozen into the postapocalyptic synchrony of history’s end.

Weekend reflects a period of gathering crisis in most of the developed world, a time of intense politicization among young people in revolt against the inequalities of capitalism, America’s neocolonial war in Vietnam, middle-class materialism, and sexual hypocrisy, among other things; widespread disgust with both American imperialism and the sclerotic communism of the Soviet Union produced a highly energized revolutionary movement, strongly influenced by the Chinese Cultural Revolution and less remarkable for any legible goals than for its bloody-minded rejection of the status quo. “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome with more horror,” someone says near the end of the film, providing a belated raison d’e?tre for everything we’ve already seen. The revolutionary future Godard introduces, spearheaded by armed hippies identified as the Seine- et-Oise Liberation Front (FLSO), is arguably as repulsive as anything else in Weekend, but Godard withholds judgment. Obviously, the piratical forest dwellers represent what would soon be known as “the generation of May ’68,” as do the members of the Maoist commune in Godard’s preceding film, La Chinoise (1967); Godard presents them as the inevitable outcome of a historical process, and surrenders the last part of his film to an endless tribal massacre. But he also indicates the absurdity of the romantic apocalypse on-screen. Life is a tragedy for those who feel, a comedy for those who think; in Weekend, Godard is definitely opting for comedy.

Godard is said to have told his usual crew to look for other work after wrapping Weekend; he was finished with most of what movies were expected to look and sound like, and devoted much of the next decade to ideologically oversaturated films that were more like Marxist-Leninist slide lectures than movies. The final title card announces the “end of cinema.” Weekend was the last “real” movie Godard made for several years, until Tout va bien (1972)—“real” in the sense that it relies on cinematic illusion, however thin, to move from point A to point B, relates a story one can summarize coherently, and could, conceivably, be viewed with pleasure even by an audience indifferent to its sociological and political didacticism. But how much richer Weekend is for its didacticism, which gives this film its historical prescience while inviting us to laugh with it and at it at the same time—offering the pleasure of uninhibited black comedy and an ever fresh spite toward everything meretricious and fake.

-Gary Indiana

Jean-Luc Godard’s cathartically brilliant and infuriating masterpiece Weekend is one of the key films of the late 1960’s. It is on one hand a chaotically brilliant black comedy and on the other hand a surrealistically acid disdain on the nihilistic bourgeoisie consumer society. Weekend is less like a film and more like a abstract political collage as its pop art color scheme and two-dimensional character’s go on a surreal cross-country road trip which descents down a fantastical rabbit hole of utter hell. A married couple named Corinne and Roland, are plotting each other’s demise with their respective lovers, while at the same time both planning to head out by car for Corinne’s parents’ home in the country to secure their inheritance from Corinne’s dying father by murdering him; maybe her mother as well if she refuses to split the inheritance. All but three scenes in Weekend take place out-of-doors, in meadows and woods, on roadways and farms. In one of the iconic sequences of the film Corinne and Roland bully themselves through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross-section of the French middle class, as one long take shows a debris field of wrecked and burning vehicles, dead corpses, and repeated honking horns. It is a very long traffic jam, as this one long take continues without interruption for perhaps three-quarters of a mile. “Politics is a traveling shot,” Godard told critics, as the road unleashes the two protagonists inner beastliness and primitive instincts, as they route through a hellish landscape of predatory unconscious that resembles a projection of political violence, angry ideology, allusions to ideas and of high-culture.

Corinne and Roland’s trip becomes a chaotically picaresque journey through a French countryside populated by bizarre characters and punctuated by violent car accidents. Oblivious to the unlikelihood of encountering several of its characters, such as when the two lovers suddenly get carjacked by a magician who proves he is authentic by having Corinne pull a rabbit from under the dashboard of the car. They also encounter historical figures like Saint-Just (Jean-Pierre Léaud) who makes a political speech during the French Revolution, and two characters of literary fact and fiction: Tom Thumb from Mother Goose and Emily Bronte author of Wuthering Heights. Both are refracted through the lens of Louise Carroll. Roland ultimately says, “What a rotten film, all we meet are crazy people.” If the past is there to teach us things, Corinne and Roland aren’t prepared to keep on learning; as it only takes a drop of bewilderment or a line of ‘useless’ poetry to unleash their inner beastliness and furious contempt and rage.

Godard repeatedly fractures the narrative with flash cuts and inter-titles while he greatly tests the patience of his audience with such fascinating sequences of a barnyard recital of Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 18, as the camera makes a complete 360-degree rotation, as we see the entire barnyard pianist, listeners, passersby, and the camera crew three times in one sequence. In one of the most fascinating sequences in the film which occurs early on in the film, Corinne’s lover assumes the role of psychiatrist, sitting at a desk in a darkened office while Corinne sits on a desk in her bra and panties and describes a recent three-way episode with a different lover and his girlfriend, an orgy, involving eggs and a bowl of milk; loosely borrowed from Bataille’s Histoire de l’oeil. This episode is obviously a direct parody of Bibi Andersson’s emotionally overwrought ‘orgy monologue’ in Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece Persona, rendered flat and passionless by Corinne’s bored delivery, as the camera’s slow zooming in and out in near darkness on the barely distinguishable figures, and obvious B-movie theme music that occasionally drowns out her voice. Godard establishes here an atmosphere of neurotic apprehension and narrative unreliability sustained throughout the rest of the film. “Is this a dream or did it really happen?” “I don’t know.”

After bullying their way through an epic traffic jam that serves as a cross-section of the French middle class, the sullen, perpetually bickering couple proceed with rapacious single-mindedness into consumer ID, obsessed with clothes and cars and cash, they treat every stranger as an obstacle or an opportunity. Weekend is a highly driven by primitive instinct, as the film is rich with ideas, allusions to high culture,and showstopping longueurs of political theater. Several of the ideas come from Karl Marx and Jacques Lacan, as Godard seizes choice fragments from the sixties intellectual zeitgeist and layers them into an abrasive strangely compelling collage. The techniques of Weekend, however, comes from Brecht. The film excludes any emotional identification with its protagonists, and they are less developed three-dimensional characters that we come to care about, and more nihilistic archetypes that ultimately deserve their comeuppance. (Corinne’s only emotional moment occurs when her Hermes pocketbook is incinerated in a head-on collision.) In many ways this fantastic world of hell that Godard has created for his two main character’s seems to mirror the prisons that Spanish director Luis Bunuel would create for the wealthy and privileged in several of his dark satires. And so it’s not so surprising one of the chapter’s in Weekend is named after Bunuel’s classic film, which not only involves the slow deterioration and breakdown of human civilization, but also ends in the shocking murder and cannibalization of another human being. Moreover, Corinne and Roland are conscious of being characters within a movie, as Weekend’s fistfights, shootings, stabbings, and highway carnage don’t simulate violence so much as transmit an idea of violence. The bloodshed is so deliberately fake that when a realistic violent scene is shown in which a real pig has its throat cut, it comes across as a powerful and disturbing shock to the viewer.

In what I believe to be the weakest part of the film is an extended philosophical sequence in which two garbage-men eat sandwiches while staring into the camera. The camera completely stops everything dead in its track to deliver a political theoretical voice-over monologue about colonialism and exploitation. The scene is essential for the understanding of the large overall premise of Weekend, and yet at the same time the sequence is so excruciatingly obvious and unsubtle that critics at this time would advise the audience to go out for coffee as soon as it started. Weekend is constructed like a problem in logic or a mathematical theorem. Virtually every scene reflects the unraveling of Rousseau’s social contract and points to inevitable disintegration into tribal activism. Godard, who trained as an ethnologist, adapted the film’s structure from Freidrich Engel’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. Engels developed ideas from the anthropologist Lewis Morgan’s study of the Iroquois and Seneca tribes, which posits that, “according to the materialist conception, the determining factor in history is…the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life.”

Weekend reflects a period of gathering crisis in most of the developed world, a time of intense politicization among young people in revolt against the inequalities of capitalism, America’s neocolonial war in Vietnam, middle-class materialism, and sexual hypocrisy, among other things; widespread disgust with both American imperialism and the sclerotic communism of the Soviet Union produced a highly energized revolutionary movement, strongly influenced by the Chinese Cultural Revolution and less remarkable for any legible goals than for its bloody-minded rejection of the status quo. “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome with more horror,” a FLSO leader says near the end of the film, providing a belated raison for everything we’ve already seen. The revolutionary future Godard introduces, spearheaded by radical armed hippies identified as the Seine- et-Oise Liberation Front (FLSO), is arguably as repulsive as anything else in Weekend, but Godard withholds judgment. Obviously, the piratical forest dwellers represent what would soon be known as “the generation of May ’68,” as do the members of the Maoist commune in Godard’s preceding film, La Chinoise in 1967; Godard presents them as the inevitable outcome of a historical process, and surrenders the last part of his film to an endless tribal massacre. But he also indicates the absurdity of the romantic apocalypse on-screen. Life is a tragedy for those who feel, a comedy for those who think; in Weekend, Godard is definitely opting for comedy. Godard is said to have told his usual crew to look for other work after wrapping Weekend; as he was finished with most of what movies were expected to look and sound like, and devoted much of the next decade to ideologically oversaturated films that were more like Marxist-Leninist slide lectures than movies. The final title card announces the “end of cinema.” Weekend was the last ‘real’ movie Godard made for several years, until Tout va bien.” But how rich and revolutionary Weekend was for its references to classic cinema (the tribal broadcasts cinematic code names were those of The Searchers, Battleship Potemkin and Johnny Guitar and of its film homages to Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar, and Luis Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel.) which gives this film its historical prescience while inviting us to laugh along with it at it at the same time, offering the pleasure of uninhibited black comedy and an ever fresh spite toward everything neurotic and politically allegorical.

Weekend reflects a period of gathering crisis in most of the developed world, a time of intense politicization among young people in revolt against the inequalities of capitalism, America’s neocolonial war in Vietnam, middle-class materialism, and sexual hypocrisy, among other things; widespread disgust with both American imperialism and the sclerotic communism of the Soviet Union produced a highly energized revolutionary movement, strongly influenced by the Chinese Cultural Revolution and less remarkable for any legible goals than for its bloody-minded rejection of the status quo. “The horror of the bourgeoisie can only be overcome with more horror,” a FLSO leader says near the end of the film, providing a belated raison for everything we’ve already seen. The revolutionary future Godard introduces, spearheaded by radical armed hippies identified as the Seine- et-Oise Liberation Front (FLSO), is arguably as repulsive as anything else in Weekend, but Godard withholds judgment. Obviously, the piratical forest dwellers represent what would soon be known as “the generation of May ’68,” as do the members of the Maoist commune in Godard’s preceding film, La Chinoise in 1967; Godard presents them as the inevitable outcome of a historical process, and surrenders the last part of his film to an endless tribal massacre. But he also indicates the absurdity of the romantic apocalypse on-screen. Life is a tragedy for those who feel, a comedy for those who think; in Weekend, Godard is definitely opting for comedy. Godard is said to have told his usual crew to look for other work after wrapping Weekend; as he was finished with most of what movies were expected to look and sound like, and devoted much of the next decade to ideologically oversaturated films that were more like Marxist-Leninist slide lectures than movies. The final title card announces the “end of cinema.” Weekend was the last ‘real’ movie Godard made for several years, until Tout va bien.” But how rich and revolutionary Weekend was for its references to classic cinema (the tribal broadcasts cinematic code names were those of The Searchers, Battleship Potemkin and Johnny Guitar and of its film homages to Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar, and Luis Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel.) which gives this film its historical prescience while inviting us to laugh along with it at it at the same time, offering the pleasure of uninhibited black comedy and an ever fresh spite toward everything neurotic and politically allegorical.