Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

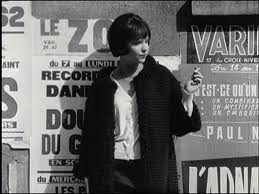

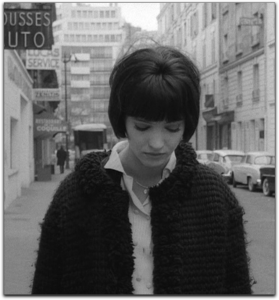

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Vivre sa vie Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Vivre Sa Vie (or in English titled My Life to Live), is the tragic story on a woman’s slow descent into prostitution and death. Directed by the legendary Jean-Luc Godard, he divides the film into 12 tableaux, very similar to a novel. The actress who plays the character of Nana is the beautiful and legendary Anna Karina who was Godard’s current wife at the time. Vivre Sa Vie is one of Godard’s most heartbreaking films about the social situation of women and their struggles in an unsympathetic world, as it became one of the most influential films of The French New Wave movement. The French New Wave was considered a certain European art form during the late 50s and 60s led by a group of young filmmakers that included Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette who were connected to the magazine ‘Cahiers du cinema’. The idea of The French New Wave film was that it should seem personal and freewheeling, where the directors often chose to shoot on location, using natural lighting and often using hand-held cameras which added to the experimental feel of the films. When originally released Vivre Sa Vie wasn’t as highly praised as Godard’s earlier New Wave hit Breathless, but throughout the years it is now considered not only one of Godard’s very best films, but his most studied and adored by fans and critics. Godard’s unique literary narration, creative camera shots and long philosophical dialog sequences between several of his characters closely resembles the style and techniques of director Quentin Tarantino, most famously with his film Pulp Fiction. [fsbProduct product_id=’836′ size=’200′ align=’right’]For instance, Vivre sa Vie is set up as a literary narration separated by different chapters, which is a similar storytelling approach that Tarantino uses for his films. Nana’s sporting her infamous ebony bob in the film is later worn by Uma Thurman’s character Mia in Pulp Fiction, (ironically Karina’s bob was an homage to the legendary silent actress Louise Brooke from Pandora’s Box, whose character also falls into prostitution and meets a violent death.) There’s the classic jukebox dance sequence, which is reminiscent of Mia and Vincent’s dance competition at Jack Rabbit Slims. And finally there is the classic discussion between philosopher Brice Parian in which Nana questions why people feel the need to always talk, which is greatly paralleled to Mia’s conversation with Vincent Vega. One of Vivre Sa Vie’s major themes that Godard seems to explore is the subject of verbal and non-verbal communication between people within real life and also within the cinema. In one of the greatest sequences in the film the character of Nana spends the last money she has on the viewing of Carl Dreyer’s silent masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc. The audience witnesses Nana weep as she identifies with Joan, the teary eyed martyr on the movie screen, as Godard brilliantly captures and iconized the tragic art of the cinema, in a heartbreaking sequence without the use of words.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Vivre sa vie Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Vivre Sa Vie (or in English titled My Life to Live), is the tragic story on a woman’s slow descent into prostitution and death. Directed by the legendary Jean-Luc Godard, he divides the film into 12 tableaux, very similar to a novel. The actress who plays the character of Nana is the beautiful and legendary Anna Karina who was Godard’s current wife at the time. Vivre Sa Vie is one of Godard’s most heartbreaking films about the social situation of women and their struggles in an unsympathetic world, as it became one of the most influential films of The French New Wave movement. The French New Wave was considered a certain European art form during the late 50s and 60s led by a group of young filmmakers that included Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette who were connected to the magazine ‘Cahiers du cinema’. The idea of The French New Wave film was that it should seem personal and freewheeling, where the directors often chose to shoot on location, using natural lighting and often using hand-held cameras which added to the experimental feel of the films. When originally released Vivre Sa Vie wasn’t as highly praised as Godard’s earlier New Wave hit Breathless, but throughout the years it is now considered not only one of Godard’s very best films, but his most studied and adored by fans and critics. Godard’s unique literary narration, creative camera shots and long philosophical dialog sequences between several of his characters closely resembles the style and techniques of director Quentin Tarantino, most famously with his film Pulp Fiction. [fsbProduct product_id=’836′ size=’200′ align=’right’]For instance, Vivre sa Vie is set up as a literary narration separated by different chapters, which is a similar storytelling approach that Tarantino uses for his films. Nana’s sporting her infamous ebony bob in the film is later worn by Uma Thurman’s character Mia in Pulp Fiction, (ironically Karina’s bob was an homage to the legendary silent actress Louise Brooke from Pandora’s Box, whose character also falls into prostitution and meets a violent death.) There’s the classic jukebox dance sequence, which is reminiscent of Mia and Vincent’s dance competition at Jack Rabbit Slims. And finally there is the classic discussion between philosopher Brice Parian in which Nana questions why people feel the need to always talk, which is greatly paralleled to Mia’s conversation with Vincent Vega. One of Vivre Sa Vie’s major themes that Godard seems to explore is the subject of verbal and non-verbal communication between people within real life and also within the cinema. In one of the greatest sequences in the film the character of Nana spends the last money she has on the viewing of Carl Dreyer’s silent masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc. The audience witnesses Nana weep as she identifies with Joan, the teary eyed martyr on the movie screen, as Godard brilliantly captures and iconized the tragic art of the cinema, in a heartbreaking sequence without the use of words.

PLOT/NOTES

EPILOGUE:

During the opening credits the character of Nana S is posed between three different face shots. The first side is a side shot of Nana’s face and then the camera switches viewpoints and shows a front shot of Nana looking directly at the screen and then switches to the opposite side of her face. This interesting opening scene which feels more like test shots for a film or like police mug shots.

I. A CAFE – NANA WANTS TO GIVE UP- PAUL- THE PINBALL MACHINE:

Nana S is a young girl from the provinces who has lived in Paris for some time who has left her husband and her small son because of her dream of becoming an actress. The film opens inside a coffeehouse somewhere in the section of Vaugirard. Nana is seated at a counter next to her estranged husband Paul and yet the camera does not show they’re faces and only shows the back of both of their heads.

The both of them are talking about they’re child, and of Nana’s continuing goal of wanting to be an actress. Paul is an unsuccessful journalist and when he asks her if she has any money she says and repeats, “what do you care? What do you care? What do you care? I just wanted to deliver that line a specific way. I didn’t know the best way to say it. Or I did know, but I don’t anymore.”

Nana then tells Paul how she exhausted she is loving him and how she just wants to die. You can gather from the conversation between the two of them that they love each other and do meet up to see each other quite often. When Nana explains to Paul how she is meeting up with a man who will take her picture and sent her pictures to the movie studios, but her husband believes her dream to be a movie star to be nonsense. Nana gets up and walks over to the pinball machine in the café with Paul following behind.

While Nana plays the machine Paul says that he thought of some essays his father was reading from several of his students at dinner the night before. The students wrote an essay on their favorite animals, one of them in particular was about a bird. While he describes the story the camera shifts over to Nana and leaves Paul completely out of the frame as you hear him say, “A bird is an animal with an inside and an outside. Take away the outside and the inside is left. Take away the inside and you see its soul.”

II. THE RECORD SHOP – 2,000 FRANCS- NANA LIVES HER LIFE:

The next chapter shows where Nana works at a record shop where she is a sales girl. Customers are coming up and asking her for artists like Rafael Romeo and Judy Garland. During work Nana is asking several of her co-workers for 2,000 francs for her rent. A coworker reads a story to Nana that she thought was interesting from a magazine while the camera pans through the stores large window watching people outside on the street.

“He gazed at the turquoise, star-laden sky and then turned to me. ‘you live your life intensely, so logically’, I interrupted him. ‘You attach too much importance to logic.’ For a few seconds I was filled with a bitter sense of triumph. No more broken heart, no more struggle to live again. No probing questions to face while masking one’s defeat. Yes, a truly elegant way of breaking this deadlock.”

III. THE CONCIERGE – PAUL:

That evening Nana’s landlady refuses to give Nana entrance into her apartment until she comes up with the rent. That next day when meeting up with Paul she looks at pictures of her young son. Paul invites her out of eat but she turns him down and decides to go see a movie with another man later that evening.

Nana walks into the theatre and spends her last few francs to see the classic silent The Passion of Joan of Arc directed by Carl Theodor Dryer and starring Maria Falconetti. Nana is in complete silence as she is emotionally moved by a powerful scene of Joan of Arc where one of the nobles asks Joan what her great victory is and Joan answers, “it will be my martyrdom.” When he asks her deliverance she states, “Death.”

Nana closes her eyes with a tear rolling down her face in pain at the word ‘death,’ as she somewhat relates to the pain that Joan endures. After the movie, Nana ditches her date to meet up with the man who promised to take photos of her inside a bakery. When they meet up and discuss what she has to do, the photographer tells her she must undress in the photos. She at first is reluctant in wanting to go through with it, but eventually decides to do it and leaves the coffee shop with him.

IV. THE POLICE- NANA IS QUESTIONED:

In an interesting scene, Nana is in a police station giving her statement to an officer on her being caught when she tried to steal 1,000 francs from a woman on the street and when the woman caught her trying to steal from her she then brought charges against her. The officer then asks what she is going to do and who she is going to stay with and Nana doesn’t even know.

V. THE BOULEVARDS-THE FIRST MAN – THE ROOM:

Nana is slowly walking down the Champes Elyees with her head down as the camera pans past a woman prostituting herself on the street. On the rue Washington, a man walks up to her and looks her up and down and then asks her, “mind if I come along with you?”

Evening though all this is a misunderstanding, Nana automatically says yes and they walk as the man turns to her and asks, “is this it?” Nana looks up and sees a neon sign that says ‘Hotel.’ She again says yes as they walk inside the Hotel and they both get a room.

Nana closes the blinds and then asks the man for 4,000 francs. He gives her 5,000 and she doesn’t have change. He says keep it anyways and he starts to kiss her as Nana struggles to avoid being kissed on the lips.

VI. RENCONTRE AVEC YVETTE- UN CAFE DE BANLIEUE- RAOUL -MITRAILLADE DEHORS:

Nana runs into an old friend named Yvette and they decide to have lunch together at a diner. When entering the diner they walk past Yvette’s pimp named Raoul who is playing at the pinball machine.

While the two ladies sit down and talk Yvette discusses how her husband left her and her children and she gradually had to become a prostitute because it was the easiest way to survive. Nana says to her, “I think we’re always responsible for our actions. We’re free. I raise my hand…I’m responsible. I turn my head to the right…I’m responsible. I’m unhappy…I’m responsible. I smoke a cigarette…I’m responsible. I shut my eyes…I’m responsible. I forgot that I’m responsible, but I am.”

Nana looks over at another couple and a man playing a pop song on the jukebox. Yvette walks over to Raoul and he asks her if Nana is a lady or a tramp. He then says, “Insult her. If she’s a tramp, she’ll get angry. If she smiles, she’s a lady.” Raoul then sits down and introduces himself to Nana and when he insults her, Nana laughs in which passes Raoul’s test of being a lady.

The three of them move towards the pinball machine and play a game when suddenly a police raid breaks out on the street as you hear machine guns and a man runs into the diner after being shot by the police.

VII. THE LETTER – RAOUL AGAIN-THE CHAMPS- ELYSEES:

The next shot shows a letter being written at the very same restaurant. Nana is writing the letter to a woman in the south of France whose address has been given to her by Yvette. Nana describes within the letter her character traits, her height, weight, ect, and that she is pretty.

Suddenly Raoul sits down next to her. Nana says to him, “you skipped out quickly the other day, when that crook was shot outside the café. You just vanished.” Raoul tells her how he doesn’t think they were crooks, but were more political. He then tells her it would be better for her to stay in Paris, that she could make more money. He then says, “For me there are three types of girls, those with one expression, those with two and those with three.”

When he asks her if she ever tried to make it as an actress she explains that she did try two years ago. After the conversation Nana accepts his offer on working for him as her prostitute and quits her job at the record shop. Before leaving the restaurant Raoul inhales his cigarette and kisses Nana while she then blows out his smoke.

VIII. AFTERNOONS- MONEY- SINKS -PLEASURE -HOTELS:

In one of the most interesting scenes in the film you hear all the questions that Nana asks her pimp Raoul on the basic rules of being a prostitute.

Some of her questions are, “Do you have to register somewhere?… What time do you have to get up?…” Some of his answers are, “the prostitute earns all she can by trading on her charms to build up a good clientelle and establish the best working condition… Although beauty is an important factor in a prostitute’s career, it establishes her place in the hierarchy and attracts the attention of the pimp, since her physical allure can be a source of great profit…”

During this monologue of questions and answers you see Nana work as she brings in several different men to hotel rooms as you watch her undressing and making love to her clients. In one famous shot it shows her with empty eyes embracing one of her clients over his shoulder while she has a smoke, as the time frame within this monologue seems ambiguous, as it could of took place within a week or several months.

IX. A YOUNG MAN -LUIGI- NANA WONDERS WHETEHR SHE’S HAPPY:

Raoul takes Nana to a friend named Luici’s at his bistro and Nana meets some interesting characters: one which pretends he’s blowing up a large balloon before it pops.

In a memorable Godard like interruption the film stalls and becomes a sort of musical as Nana puts on a pop song from the jukebox and starts to do a crazy new dance, teasing a man playing pool and a man playing a pinball machine. (You can see how this scene influenced Tarantino in which he made an homage in the dance contest of Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction.)

X. THE STREETS -A GUY-HAPPINESS IS NO FUN:

Nana is on the street back against the wall trying to pick up clients. When she picks up a client she takes him back to a hotel and when she finds out he shoots photographs she tells him how she has been in a picture with Eddie Constantine. (In which the actress Anna Karina has in Godard’s Alphaville.)

When the client says what he wants his voice becomes mute which probably suggests a ménage à trois as you then watch Nana go from door to door in the hotel asking one of the other prostitutes if she can join them.

Interestingly enough when she brings another girl back to the room the client doesn’t want Nana to join in and so Nana sits and patiently has a smoke on the edge of the bed.

XI. PLACE DU CHATELET -A STRANGER- NAN, THE UNWITTING PHILOSOPHER:

One of the few scenes that breaks away from Nana and her story on prostitution and is more about her having a philosophical café discussion with Brice Parain (who was a life philosopher.) They discuss communication, language and love as Nana questions who she is and her identity.

Nana tells Brice, “It’s funny. Suddenly I don’t know what to say. It happens to me a lot. I know what I want to say. I think about whether they’re the right words. But when the moment comes to speak, I can’t say it.” Brice then tells her a story of Quadi from the Three musketeers and when dissecting the meaning of the character Nana says, “Why must one always talk? I think one should often just keep quite, live in silence. The more one talks, the less the words mean.”

Brice answers by saying, “it’s always struck me, the fact we can’t live without speaking. We must think, and for thought we need words. There’s no other way to think. To communicate, one must speak. That’s our life. Speaking is almost a resurrection in relation to life. Speaking is a different life from when one does not speak. So, to live speaking one must pass through the death of life without speaking. I don’t think one can distinguish a thought from the words that express it. A moment of thought can only be grasped through words.”

Nana asks Brice what he thinks about love and if that should be the only truth and Brice says, “But for that, love would always have to be true. Do you know anyone who knows right off what he loves? No. When you’re 20, you don’t know. All you know are bits and pieces. You grasp at experience. At that age, ‘I love’ is a mixture of many things. To be completely at one with what you love takes maturity. That means searching. That’s the truth of life. That’s why love is a solution but on the condition that it be true.”

XII. THE YOUNG MAN AGAIN -THE OVAL PORTRAIT -PAOUL TRADES NANA:

In this last scene it shows Nana with one of her clients as he is lying on the bed reading a book by Edgar Allen Poe titled the Oval Portrait. In this chapter Nana and the client speak to each other through subtitles which bring back the silent Dreyer film The Passion of Joan of Arc.

He reads her a passage from the book which is narrated by Godard saying, “it was an impulsive movement to gain time for thought, to make sure that my vision had not deceived me, to calm and subdue my fancy for a more sober and more certain gaze. In a very few moments I again looked fixedly at the painting. The portrait, I have already said was that of a young girl. It was a mere head and shoulders, done in what is technically termed a vignette manner, much in the style of the favorite heads of Sully. The arms, the bosom, and even the ends of the radiant hair melted imperceptibly into the vague yet deep shadow which formed the background of the whole. As a thing of art, nothing could be more admirable than the painting itself.”

It then suggest that Nana has fallen in love with this man and she plans to tell Raoul that she is going to quit the prostitution buisness. Later that evening Raoul drives Nana down past a theatre ironically playing Francois Truffaut’s Jim and Jim and the aesthetics being used as the car is driving through the streets feels more like a documentary like style in which Godard uses several times in the film.

Eventually the car pulls up to another vehicle. Raoul wants to sell Nana to another pimp but the business transaction goes bad and Nana accidentally gets shot and killed by Raoul during the cross-fire.

FRENCH NEW WAVE

The New Wave was a blanket term coined by critics for a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Although never a formally organized movement, the New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of the literary period pieces being made in France and written by novelists, their spirit of youthful iconoclasm, the desire to shoot more current social issues on location, and their intention of experimenting with the film form. “New Wave” is an example of European art cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm.

Using light-weight portable equipment, hand-held cameras and requiring little or no set up time, the New Wave way of film-making presented a documentary style. The films exhibited direct sounds on film stock that required less light. Filming techniques included fragmented, freeze-frames, discontinuous editing, and long takes. The combination of objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary created a narrative ambiguity in the sense that questions that arise in a film are not answered in the end.

Alexandre Astruc’s manifesto, “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera-Stylo”, published in L`Ecran, on 30 March 1948 outlined some of the ideas that were later expanded upon by François Truffaut and the Cahiers du cinéma. It argues that “cinema was in the process of becoming a new mean of expression on the same level as painting and the novel: a form in which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel. This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the ‘camera-stylo.”

Some of the most prominent pioneers among the group, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, began as critics for the famous film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Cahiers co-founder and theorist André Bazin was a prominent source of influence for the movement. By means of criticism and editorialization, they laid the groundwork for a set of concepts, revolutionary at the time, which the American film critic Andrew Sarris called the ‘auteur theory.’

Cahiers du cinéma writers critiqued the classic “Tradition of Quality” style of French Cinema. Bazin and Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, were the dual godfather figures of the movement. These men of cinema valued the expression of the director’s personal vision in both the film’s style and script.

The ‘auteur theory’ holds that the director is the “author” of his movies, with a personal signature visible from film to film. They praised movies by Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, and made then-radical cases for the artistic distinction and greatness of Hollywood studio directors such as Orson Welles, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray. The beginning of the New Wave was to some extent an exercise by the Cahiers writers in applying this philosophy to the world by directing movies themselves.

Truffaut, with The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard, with Breathless (1960) had unexpected international successes, both critical and financial, that turned the world’s attention to the activities of the New Wave and enabled the movement to flourish. Part of their technique was to portray characters not readily labeled as protagonists in the classic sense of audience identification.

The auteurs of this era owe their popularity to the support they received with their youthful audience. Most of these directors were born in the 1930s and grew up in Paris, relating to how their viewers might be experiencing life. They were considered the first film generation to have a “film education”, knowledge of and references to film history. With high concentration in fashion, urban professional life, and all-night parties, the life of France’s youth was being exquisitely captured.

The French New Wave was popular roughly between 1958 and 1964, although New Wave work existed as late as 1973. The socio-economic forces at play shortly after World War II strongly influenced the movement. Politically and financially drained, France tended to fall back on the old popular pre-war traditions. One such tradition was straight narrative cinema, specifically classical French film.

The movement has its roots in rebellion against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), criticizing in particular the way these forms could force the audience to submit to a dictatorial plot-line. They were especially against the French “cinema of quality”, the type of high-minded, literary period films held in esteem at French film festivals, often regarded as ‘untouchable’ by criticism.

New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what was, to them, a much more comfortable and contemporary form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized. French New Wave were also influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema.

New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what was, to them, a much more comfortable and contemporary form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized. French New Wave were also influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema.

The French New Wave featured unprecedented methods of expression, such as long tracking shots (like the famous traffic jam sequence in Godard’s 1967 film Week End). Also, these movies featured existential themes, such as stressing the individual and the acceptance of the absurdity of human existence. Filled with irony and sarcasm, the films also tend to reference other films.

Many of the French New Wave films were produced on tight budgets; often shot in a friend’s apartment or yard, using the director’s friends as the cast and crew. Directors were also forced to improvise with equipment (for example, using a shopping cart for tracking shots). The cost of film was also a major concern; thus, efforts to save film turned into stylistic innovations. For example, in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, after being told the film was too long and he must cut it down to one hour and a half he decided (on the suggestion of Jean-Pierre Melville) to remove several scenes from the feature using jump cuts, as they were filmed in one long take. Parts that did not work were simply cut from the middle of the take, a practical decision and also a purposeful stylistic one.

The cinematic stylings of French New Wave brought a fresh look to cinema with improvised dialogue, rapid changes of scene, and shots that go beyond the common 180° axis. The camera was used not to mesmerize the audience with elaborate narrative and illusory images, but to play with the expectations of cinema. The techniques used to shock and awe the audience out of submission and were so bold and direct that Jean-Luc Godard has been accused of having contempt for his audience. His stylistic approach can be seen as a desperate struggle against the mainstream cinema of the time, or a degrading attack on the viewer’s supposed naivety. Either way, the challenging awareness represented by this movement remains in cinema today. Effects that now seem either trite or commonplace, such as a character stepping out of their role in order to address the audience directly, were radically innovative at the time.

Classic French cinema adhered to the principles of strong narrative, creating what Godard described as an oppressive and deterministic aesthetic of plot. In contrast, New Wave filmmakers made no attempts to suspend the viewer’s disbelief; in fact, they took steps to constantly remind the viewer that a film is just a sequence of moving images, no matter how clever the use of light and shadow. The result is a set of oddly disjointed scenes without attempt at unity; or an actor whose character changes from one scene to the next; or sets in which onlookers accidentally make their way onto camera along with extras, who in fact were hired to do just the same.

At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods, and were inspired by the generation of Italian Neorealists before them. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to the theatre.

Finally, the French New Wave, as the European modern Cinema, is focused on the technique as style itself. A French New Wave film-maker is first of all an author who shows in its film his own eye on the world. On the other hand the film as the object of knowledge challenges the usual transitivity on which all the other cinema was based, “undoing its cornerstones: space and time continuity, narrative and grammatical logics, the self-evidence of the represented worlds.” In this way the film-maker passes “the essay attitude, thinking – in a novelist way – on his own way to do essays.”

The Left Bank, or Rive Gauche, group is a contingent of filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, first identified as such by Richard Roud. The corresponding “right bank” group is constituted of the more famous and financially successful New Wave directors associated with Cahiers du cinéma. Unlike the Cahiers these directors were older and less movie-crazed. They tended to see cinema akin to other arts, such as literature. However they were similar to the New Wave directors in that they practiced cinematic modernism. Their emergence also came in the 1950s and they also benefited from the youthful audience. The two groups, however, were not in opposition; Cahiers du cinéma advocated Left Bank cinema.

Left Bank directors include Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. Roud described a distinctive “fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking”, as well as an identification with the political left. The filmmakers tended to collaborate with one another, Jean-Pierre Melville, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Marguerite Duras are also associated with the group. The nouveau roman movement in literature was also a strong element of the Left Bank style, with authors contributing to many of the films. Left Bank films include La Pointe Courte, Hiroshima mon amour, La jetée, Last Year at Marienbad, and Trans-Europ-Express.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

It’s easy to get anxious about the place of Jean-Luc Godard in our cultural slipstream. He’s held a top-shelf slot of honor that has seemed unassailable for nearly sixty years, but sometimes I fear that his currency is becoming drastically devalued in our always-renovating purgatory of digital 3-D candy corn. How long can the smoky blown-glass armature of a hand-size, self-analyzing film like Vivre sa vie survive in our Dolby-thundering moviedrome alongside giant robots, athletic aliens, superheroes, and talking chipmunks? It will remain a Godardian world, no matter what comes, but who will know it?

For now, the prime Godards are still fresher than last Friday’s blockbusters, and still miles ahead of a medium too often enraptured by empty chaos. In this context, each Godard is a chastening lesson in how humane an art cinema can really be. Of the fifteen or so Godard features of the sixties that essentially define the decade as his, Vivre sa vie, his fourth, is one of the most studied and most quoted, perhaps because its metafictional slippages are more suggested than explicit, or because the thematic meat of the film—poverty and prostitution—is topical and easily codified, at least in comparison with the other films in that oeuvre (just try to pick a thesis-worthy social issue out of Pierrot le fou or Alphaville). Godard’s interest in the politics of whoring has become the way he is most often approached academically in recent years, and not always kindly. No matter: this film pulses with sympathy and rue. The common idea that Godard is a chilly, intellectually remote filmmaker is the first notion you discard when looking at his best work today, in this new century: the films couldn’t be more intimate, impulsive, joyous, and attentive to the subjective nature of experience. Vivre sa vie may be the grimmest entry in Godard’s golden age—the heroine is named Nana, after Zola, for a reason—but its heart is on its sleeve, and tenderness radiates from the screen.

It is also, not incidentally, the third film Godard made with Anna Karina; they’d been married since the spring of 1961, and he may have never made another film so empathetic and heartbroken about the social situation of women. (Indeed, Nana’s doomed pretty-girl hopes of getting into movies, and her subsequent, matter-of-fact spiral into exploitation, could be seen as a worst-case scenario for Karina in an alternate life—there but for the grace of God goes she.) But there’s an inevitable distance, one that haunts all of Godard’s films “about” Karina and, to a significant degree, all of his portraits of women. You can’t miss his self-awareness here—the movie’s signature move is a “close-up” of the back of Karina’s head as she chats with offscreen men, a pensive trope grabbed by both Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh that neatly turns a film’s tendency toward disambiguation on its head. Godard’s shots were always about how he felt about what he saw, and this composition is the equivalent of looking but not seeing, of turning your star’s expressive power into offscreen space, of admitting to the world that, though you love this woman, you do not know her.

Vivre sa vie, broken up into twelve “tableaux,” otherwise spends an enormous amount of its time watching Karina watch and listen to others—trying to figure her out as Nana attempts, and fails, to navigate an unsympathetic world. Her one moment of release is, of course, the film’s most famous scene: the viewing of Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc in a silent, pitch-black theater, and Nana’s open weeping in pity and self-pity at Falconetti’s saucer-eyed martyr. There’s little overestimating the impact this tiny moment had on cinema at large—in a stroke, Godard iconized the Cinémathèque française lifestyle, an entire generation’s discovery of film as an art form, the capacity of classic cinema-going to be tragic and romantic and supercool, and the quintessentially Godardian idea that movies are always about their own movieness, making them not an escapist alternative to our lives but part of them. Nana is not merely being diverted by the film (she’s been kicked out of her apartment for lack of rent) but living it. Movie characters had watched films in darkened theaters before, but never had we been made to empathize so directly with the act of movie watching, and never before had that act meant so much. Watching both actresses, we are Karina, and for a brief time, we and Godard know exactly how she feels.

Not to mention, Nana is the first in a long line of movie-movie demimondaines allusively sporting Louise Brooks’s ebony bob from Pabst’s Pandora’s Box, which in the context of the narrative is as suggestive of her fate as her name. (When Tarantino co-opted the hairdo for Pulp Fiction, it was Godard he was thinking about, not Pabst.) Life is a movie, and vice versa, and anything can happen—even in this relatively somber work, a cheesy genre-film shoot-out can explode in the street, sending Karina’s lost girl running like mad in the opposite direction, as if she’s suddenly found herself in the wrong film. “Reality” is a vulnerable quantity, and amid the usual cargo of signs and wonders, Godard steers the movie toward a questioning of surface and meaning, contemplating in an extended Q&A narration the gritty mechanics of prostitution (as opposed to the fantasy it represents), and engaging Nana in a philosophical café discussion about the difficulty of truth telling with Brice Parain, a famous French philosopher who paved the way for the poststructuralists by maintaining that language begat humanity, not the other way around. Eventually, the Young Man reads aloud from Poe’s “The Oval Portrait,” the Borgesian thrust of which contemplates the costs of confusing the real and its simulacra. (“This is indeed Life itself!” the artist cries at the eponymous painting of his wife, as she wastes away.) There are scores of ways to read the film’s discourse, but the most moving may be to consider it as Godard’s manifest suspicion that, like Poe’s painter, he has loved his new and beautiful wife on film more than in real life. If A Woman Is a Woman is the Godard-Karina honeymoon and Made in U.S.A the relationship’s requiem, then you could say Vivre sa vie is the couple’s first morning after, when recriminations and hesitations begin to creep their way in.

Of course, Godard thought and wrote and spoke via cinema, so it was inevitable that he would love through it as well. Despite its topicality, the film, in the end, is about Karina, not about sex work as a phenomenon, and about how quickly she came to signify all women for Godard. One wonders what kind of 1960s there would have been if he had pursued and landed another actress. As it is, by way of Godard, Karina remains one of cinema’s greatest presences, not in terms of specific moments or “performance” but of her axiomatic role in redefining, with Godard, what movies are. You don’t watch Karina, or absorb her uncanny relationship with Godard’s camera (a bewitching rapport that has eluded Godard with any other actress, and Karina with any other director), for her diegetic conviction but for herself, alive and captured in the filmmaking moment, as if in amber. Which may also have been a facet of Godard’s thinking, as the woman lights one ritualistic cigarette after another and stares over the shoulders of her johns with darkened eyes: do we love her better on film as well? We will, also like Poe’s painter, turn around one day and find that Karina has gone the way of all flesh, of course. But she’ll still be here, hiding her feelings, twenty-one and worrisome and beloved.

-Michael Atkinson

In Vivre sa vie, Jean-Luc Godard borrowed the aesthetics of the cinéma vérité approach to documentary film-making that was then becoming fashionable. However, this film differed from other films of the French New Wave by being photographed with a heavy Mitchell camera, as opposed to the light weight cameras used for earlier films. The cinematographer was legendary Raoul Coutard, a frequent collaborator of Godard.

Vivre sa vie which was Godard’s fourth film at the time and was released shortly after Cahiers du cinéma (the film magazine for which Godard occasionally wrote) published an issue devoted to Bertolt Brecht and his theory of ‘epic theatre’. Godard may have been influenced by it, as Vivre sa vie uses several alienation effects: twelve inter-titles appear before the film’s ‘chapters’ explaining what will happen next; jump cuts disrupt the editing flow; characters are shot from behind when they are talking; they are strongly backlit; they talk directly to the camera; the statistical results derived from official questionnaires are given in a voice-over; and so on.

The film also draws from several literary writings of Montaigne, Baudelaire, Zola and Edgar Allan Poe, to the cinema of Robert Bresson, Jean Renoir and Carl Dreyer. Interestingly enough the first story that was read to Nana by her husband near the beginning of the film which tells the story of a bird and when taken apart can reveal the bird’s soul, is a contrast to the character of Nana and how throughout the film the audience will eventually be taking Nana apart and she will within time than reveal the soul that is inside her.

Nana gets into an earnest discussion with a philosopher (played by Brice Parain, Godard’s former philosophy tutor), about the limits of speech and written language. In the next scene, as if to illustrate this point, the sound track ceases and the images are overlaid by Godard’s personal narration. This formal playfulness is typical of the way in which the director was working with sound and vision during this period.

The film depicts the consumerist culture of Godard’s Paris; a shiny new world of cinemas, coffee bars, neon-lit pool halls, pop records, photographs, wall posters, pin-ups, pinball machines, juke boxes, foreign cars, the latest hairstyles, typewriters, advertising, gangsters and Americana. It also features allusions to popular culture; for example, the scene where a melancholy young man walks into a cafe, puts on a juke box disc, and then sits down to listen.

The unnamed actor is in fact the well-known singer-songwriter Jean Ferrat, who is performing his own hit tune “Ma Môme” on the track that he has just selected. Nana’s bobbed haircut replicates that made famous by Louise Brooks in the 1928 silent film Pandora’s Box, where the doomed heroine also falls into a life of prostitution and violent death. In one sequence we are shown a queue outside a Paris cinema waiting to see Jules et Jim, the new wave film directed by François Truffaut, at the time both a close friend and sometime rival of Godard.

While not being one of Godard’s best-known films, Vivre sa Vie enjoys an extremely positive critical reputation. Out of all of Godard’s films this one closely resembles the style director Quentin Tarantino uses decades later in his hit film Pulp Fiction. For instance, you have Nana’s classic ebony bob haircut that Uma Thurman wears, the classic jukebox dance sequence, which is reminiscent of Mia and Vincent’s dance sequence at Jack Rabbit Slims, and even Mia questioning why people feel the need to talk, which is greatly similar to Nana’s conversation between philosopher Brice Parain.

Susan Sontag, author and cultural critic, has described Godard’s achievement in Vivre sa vie as “a perfect film” and “one of the most extraordinary, beautiful, and original works of art that I know of.” The French critic Jean Douchet makes a comparison to Vivre sa Vie and the work of Kenji Mizoguchi and its themes about a woman’s place in society. She writes,”Godard’s film would have been impossible without Street of Shame, Kenji Mizoguchi’s last and most sublime film.” According to critic Roger Ebert, “The effect of the film is astonishing. It is clear, astringent, unsentimental, abrupt.” and he has it included on his ‘Great Movies’ list.

Vivre sa Vie is a simple story that’s told under 90 minutes. Nana, played by Anna Karina, was Godard’s wife at the time and she at first was worried that her part in this film would ruin her career. Her character in the film is never really explored and she remains more of a mystery which shows a woman who is always smoking and hiding her feelings. She does not have a home and is broke. Why is that? Why did she leave her husband and is not interested in seeing her child? The movie does not give answers, and her character becomes more of an enigma, an impassive and mysterious character. Each beginning scene begins with music by Michel Legrand which stops abruptly, to begin again with the next scene. It is never really said how long of a time period this story took place and Godard never seemed to care. Nana’s downward spiral into prostitution and then to her death could have been several months or several years; it’s never really said.

Raoul Coutard was Godard’s main cinematographer who worked side-by-side with Godard during this period and has creating interesting camera shots of the back of a character’s head, or tracking shots that slowly move back and forth pulling some people out and bringing other people into the frame. Godard has said, “The film was made by sort of a second presence, the camera is not just a recording device but a (ital) looking (unital) device, that by its movements makes us aware that it sees her, wonders about her, glances first here and then there, exploring the space she occupies, speculating.”

There are several literary discussions within the film and the film itself is set up like a novel as well. (which was something Quentin Tarantino uses in his plot structure for most of his films.) The movie is split in 12 sections, each one with titles like an old-fashioned novel that shows sections of Nana’s life, but does not go into great detail. She plays pinball. She works in a record store. She needs money. She tries to steal her flat key from the office. She dances to a pop song on the juke box. She attends a screening of the film The Passion of Joan of Arc which is ironically is about a woman who is judged by men.

Godard is known mostly for his quick cuts and sudden edits and yet this film has very few of them and more slow camera tracking shots. The film expresses how the camera looks at the characters in the film and the things going on around them, and in many ways the camera is a character of its own. Godard uses themes that he has used in many of his films before like for instance the dance Nana does around her pimp and his comrades. A musical dance sequence is done in Godard’s Band of Outsiders and Pierrot Le Fou as well. Philosophical debates have been done especially in his much later films like Masculine feminin and 2 or 3 Things I know about Her. The ending of the film involves a city shootout with has been done before in Band of Outsiders and most famously in Breathless which usually involves petty thieves and gangsters.

Jean-Luc Godard is considered one of the greatest filmmakers and has created some of the greatest French films in the world. Most famously is Breathless which revolutionized filmmaking forever with it’s cool detachment of authority figures and its quick cuts and edits. Contempt tells the story of a writer involved in the movie industry ordered to write a screenplay of Ulysses, (where director Fritz Lang makes a cameo playing himself.) Alphaville is a neo noir sci-fi thriller and Band of Outsiders is considered somewhat a companion piece to Breathless. Pierrot Le Fou was Godard’s colorful farewell to the gangster genre and yet mixes in several other genres as well. Godard later started making films which were more political essays and full of collage like images that were very philosophical like in Masculine Feminin, 2 or 3 Things I know about Her and his abstract surreal film Weekend.

Sadly Jean-Luc Godard and other great artistic filmmakers are slowly being forgotten because of the mainstream popularity of big budget entertainments. In a film world now full of giant robots, comic book superheroes, and 3D space epics, Godard’s films still seem more fresh and relevant than any of them could ever be. Godard defined the 60’s and changed cinema forever creating the French New Wave with several other French directors most famously Francois Truffaut. And yet less and less of the newer generations know who he is or even care. Film critic Roger Ebert said on Godard, ‘We loved his films. As much as we talked about Tarantino after Pulp Fiction we talked about Godard in those days. I remember a sentence that became part of my repertory: ‘His camera rotates 360 degrees, twice, and then stops and moves back in the other direction just a little to show that it knows what it’s doing!’ And now the name Godard inspires a blank face from most filmgoers. Subtitled films are out. Art films are out. Self-conscious films are out. Films that test the edges of the cinema are out. Now it is all about the mass audience: It must be congratulated for its narrow tastes, and catered to. And yet, idly watching television as Aerosmith is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I reflect that if they can be resurrected from the ashes of more radical decades, then why not Godard?” Godard and Anna Karina who was Godard’s wife since the spring of 1961 have never made another film that was so bleak or that has explored the tragic aspects of women in social society. I believe one of the films main themes in Vivre sa Vie is the subject of verbal and non communications between people within real life and also within the cinema. Several shots in the film you hear character’s having complete conversations with one another without the camera ever moving or showing the character’s speaking the words that are being said. They’re even times in the film where you see the character’s speaking through subtitles and yet the character’s aren’t speaking verbally, which is greatly similar to a silent film. And than you have one of the great scenes in the film where Nana has a philosophical conversation with Brice Parain about the power of words as she says, ‘Why must one always talk? I think one should often just keep quite, live in silence. The more one talks, the less the words mean.” Even though most of Nana’s character is slightly unknown and the decisions she makes are not made very clear, the two scenes that seem to fully express what Nana is feeling involve subtitles and no verbal communication. The man she has met and has fallen in love with near the end of the film, the communication between the two of them is all completely subtitled, and the scene of her sad expression tearing up while watching Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, they’re also no words verbally said on the screen, or between her and the date she is with. Maybe Godard is suggesting that true emotions don’t need to be verbal and that silence can express more on how a person is feeling then most films that have to explain or verbalize what a character is thinking or feeling. At the end of the film the young man she has fallen in love with is reading Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘The Oval Portrait’ and he is explaining the cost of the real vs the image. “This is indeed Life itself!” the artist cries out lovingly at the portrait of his wife. Sadly at this stage of the film when Nana finally falls in love with a man and wants to quit the lifestyle she is in, it already is too late. In some ways that Edgar Allen Poe story that was read can be looked at as a contrast to Godard and how he might have felt on his wife portrayed on screen vs the woman he was married to in real life. The story reveals Godard’s true love for her as the story also reveals the upcoming death of the character of Nana. Karina and Godard were magnificent in every film they did together and Karina became an icon of the 1960s and signified what all women stood for with the director. Her performance in this film is one of her most iconic roles and in many ways cannot be matched; and Godard and Karina have also never been better when working without one another as well.

Sadly Jean-Luc Godard and other great artistic filmmakers are slowly being forgotten because of the mainstream popularity of big budget entertainments. In a film world now full of giant robots, comic book superheroes, and 3D space epics, Godard’s films still seem more fresh and relevant than any of them could ever be. Godard defined the 60’s and changed cinema forever creating the French New Wave with several other French directors most famously Francois Truffaut. And yet less and less of the newer generations know who he is or even care. Film critic Roger Ebert said on Godard, ‘We loved his films. As much as we talked about Tarantino after Pulp Fiction we talked about Godard in those days. I remember a sentence that became part of my repertory: ‘His camera rotates 360 degrees, twice, and then stops and moves back in the other direction just a little to show that it knows what it’s doing!’ And now the name Godard inspires a blank face from most filmgoers. Subtitled films are out. Art films are out. Self-conscious films are out. Films that test the edges of the cinema are out. Now it is all about the mass audience: It must be congratulated for its narrow tastes, and catered to. And yet, idly watching television as Aerosmith is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I reflect that if they can be resurrected from the ashes of more radical decades, then why not Godard?” Godard and Anna Karina who was Godard’s wife since the spring of 1961 have never made another film that was so bleak or that has explored the tragic aspects of women in social society. I believe one of the films main themes in Vivre sa Vie is the subject of verbal and non communications between people within real life and also within the cinema. Several shots in the film you hear character’s having complete conversations with one another without the camera ever moving or showing the character’s speaking the words that are being said. They’re even times in the film where you see the character’s speaking through subtitles and yet the character’s aren’t speaking verbally, which is greatly similar to a silent film. And than you have one of the great scenes in the film where Nana has a philosophical conversation with Brice Parain about the power of words as she says, ‘Why must one always talk? I think one should often just keep quite, live in silence. The more one talks, the less the words mean.” Even though most of Nana’s character is slightly unknown and the decisions she makes are not made very clear, the two scenes that seem to fully express what Nana is feeling involve subtitles and no verbal communication. The man she has met and has fallen in love with near the end of the film, the communication between the two of them is all completely subtitled, and the scene of her sad expression tearing up while watching Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, they’re also no words verbally said on the screen, or between her and the date she is with. Maybe Godard is suggesting that true emotions don’t need to be verbal and that silence can express more on how a person is feeling then most films that have to explain or verbalize what a character is thinking or feeling. At the end of the film the young man she has fallen in love with is reading Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘The Oval Portrait’ and he is explaining the cost of the real vs the image. “This is indeed Life itself!” the artist cries out lovingly at the portrait of his wife. Sadly at this stage of the film when Nana finally falls in love with a man and wants to quit the lifestyle she is in, it already is too late. In some ways that Edgar Allen Poe story that was read can be looked at as a contrast to Godard and how he might have felt on his wife portrayed on screen vs the woman he was married to in real life. The story reveals Godard’s true love for her as the story also reveals the upcoming death of the character of Nana. Karina and Godard were magnificent in every film they did together and Karina became an icon of the 1960s and signified what all women stood for with the director. Her performance in this film is one of her most iconic roles and in many ways cannot be matched; and Godard and Karina have also never been better when working without one another as well.