Un Chien Andalou (1929)

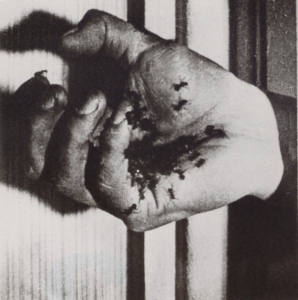

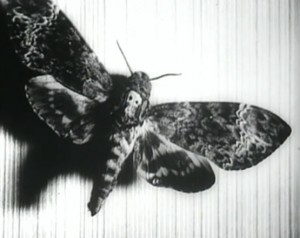

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Un Chien Andalou Bunuel Dali” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Within the world of artistry, tapping into the dreams and the unconscious mind have always been a fascinating theme to interpret and explore, and some of the great artists focus a lot of their ideas and theories in trying to understand the illogical mysteries of the conscious and unconscious. The great Spanish director Luis Bunuel once was asked what he would do if he had 20 years to live and he replied: “Give me two hours a day of activity, and I’ll take the other 22 in dreams, provided I can remember them.” Dreams were the framework of several of his avant-garde films, starting early on during his early days with surrealist artist Salvatore Dali and right to the very end in Paris during the late 1970’s. The relationship between dream states and the conventional narratives of the cinema were some of the aesthetics that Bunuel seemed to bring out of his work throughout his life giving him a distinctive and personal quality that was identifiable almost immediately, as is the same with other great film artists like Federico Fellini, Andrei Tarkovsky and Alfred Hitchcock. Un Chien Andalou was Bunuel’s first film written in collaboration with Salvador Dali and its title which translated to ‘An Andalusian dog’, doesn’t make logical sense along with anything else within the film, nor was it meant to. Un Chien Andalou remains one of the most famous short films in the world and sooner or later any film buff and cinephile will come across seeing it, probably more than once. Un Chien Andalou’s basic purpose was simple: To create a scandal among audiences and to shock, disturb and startle them. Critic Ado Kyrou said, “For the first time in the history of the cinema a director tries not to please but rather to alienate nearly all potential spectators.” [fsbProduct product_id=’832′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Today its revolutionary style and shocking images of a Freudian sexual nature are still discussed by film buffs, whether its the image of the moon followed by the image of a man with a razor slicing a woman’s eye (actually it was a calf’s eye), the hole in the hand with several ants emerging, the transvestite on a bicycle, a severed hand on the sidewalk with a stick poking at it, a hairy armpit, a death moth, a sexual assault and the woman protecting herself with a tennis racket, the attempted rapist pulling two grand pianos that seems to have dead donkeys and priests on top of it; and two living statues from the waist up in sand. To describe the movie is simply to list its shots, because there is no real story to link any of these abstract images. The scandal of Un Chien Andalou has become a story of legends in the surrealist movement, in which Bunuel claimed that at the films first screening he stood behind the screen with his pockets filled with stones reading to throw at the audience in case of a disaster. Fortunately for Bunuel, he didn’t have to use them.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Un Chien Andalou Bunuel Dali” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Within the world of artistry, tapping into the dreams and the unconscious mind have always been a fascinating theme to interpret and explore, and some of the great artists focus a lot of their ideas and theories in trying to understand the illogical mysteries of the conscious and unconscious. The great Spanish director Luis Bunuel once was asked what he would do if he had 20 years to live and he replied: “Give me two hours a day of activity, and I’ll take the other 22 in dreams, provided I can remember them.” Dreams were the framework of several of his avant-garde films, starting early on during his early days with surrealist artist Salvatore Dali and right to the very end in Paris during the late 1970’s. The relationship between dream states and the conventional narratives of the cinema were some of the aesthetics that Bunuel seemed to bring out of his work throughout his life giving him a distinctive and personal quality that was identifiable almost immediately, as is the same with other great film artists like Federico Fellini, Andrei Tarkovsky and Alfred Hitchcock. Un Chien Andalou was Bunuel’s first film written in collaboration with Salvador Dali and its title which translated to ‘An Andalusian dog’, doesn’t make logical sense along with anything else within the film, nor was it meant to. Un Chien Andalou remains one of the most famous short films in the world and sooner or later any film buff and cinephile will come across seeing it, probably more than once. Un Chien Andalou’s basic purpose was simple: To create a scandal among audiences and to shock, disturb and startle them. Critic Ado Kyrou said, “For the first time in the history of the cinema a director tries not to please but rather to alienate nearly all potential spectators.” [fsbProduct product_id=’832′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Today its revolutionary style and shocking images of a Freudian sexual nature are still discussed by film buffs, whether its the image of the moon followed by the image of a man with a razor slicing a woman’s eye (actually it was a calf’s eye), the hole in the hand with several ants emerging, the transvestite on a bicycle, a severed hand on the sidewalk with a stick poking at it, a hairy armpit, a death moth, a sexual assault and the woman protecting herself with a tennis racket, the attempted rapist pulling two grand pianos that seems to have dead donkeys and priests on top of it; and two living statues from the waist up in sand. To describe the movie is simply to list its shots, because there is no real story to link any of these abstract images. The scandal of Un Chien Andalou has become a story of legends in the surrealist movement, in which Bunuel claimed that at the films first screening he stood behind the screen with his pockets filled with stones reading to throw at the audience in case of a disaster. Fortunately for Bunuel, he didn’t have to use them.

PLOT/NOTES

The film opens with a title card reading “Once upon a time”. A middle-aged man (Luis Bunuel) sharpens his razor at his balcony door and tests the razor on his thumb. He then opens the door, and idly fingers the razor while gazing at the moon, about to be engulfed by a thin cloud, from his balcony. There is a cut to a close-up of a young woman being held by the man as she calmly stares straight ahead. Another cut occurs to the moon being overcome by the cloud as the man slits the woman’s eye with the razor, and the vitreous humour spills out from it.

The subsequent title card reads “eight years later”. A slim young man (Pierre Batcheff) bicycles down a calm urban street wearing what appears to be a nun’s habit and a striped box with a strap around his neck. A cut occurs to the young woman from the first scene, who has been reading in a sparingly furnished upstairs apartment. She hears the young man approaching on his bicycle and casts aside the book she was reading (revealing a reproduction of Vermeer’s The Lacemaker). She goes to the window and sees the young man lying on the curb, his bicycle on the ground. She emerges from the building and attempts to revive the young man.

Later, the young woman assembles pieces of the young man’s clothing on a bed in the upstairs room, and concentrates upon the clothing. The young man appears near the door. The young man and the young woman stare at his hand, which has a hole in the palm from which ants emerge. A slow transition occurs focusing on the armpit hair of the young woman as she lies on the beach and a sea urchin at a sandy location. There is a cut to an androgynous young woman in the street below the apartment, poking at a severed hand with a cane while surrounded by a large crowd and a policeman.

The crowd clears when the policeman places the hand in the box previously carried by the young man and gives it to the young woman. The androgynous young woman contemplates something happily while standing in the middle of the now busy street clutching the box. She is then run over by a car and a few bystanders gather around her. The young man and the young woman watch these events unfold from the apartment window. The young man seems to take sadistic pleasure in the androgynous young woman’s danger and subsequent death, and as he gestures at the shocked young woman in the room with him, he leers at her and grasps her bosom.

The young woman resists him at first, but then allows him to touch her as he imagines her nude from the front and the rear. The young woman pushes him away as he drifts off and she attempts to escape by running to the other side of the room. The young man corners her as she reaches for a tennis racket in self-defense, but he suddenly picks up two ropes and drags two grand pianos containing dead and rotting donkeys, stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments, and two rather bewildered priests (played by Jaime Miravilles and Salvador Dali) who are attached by ropes. As he is unable to move, the young woman escapes the room. The young man chases after her, but she traps his hand, which is infested with ants, in the door. She finds the young man in the next room, dressed in his nun’s garb in the bed.

The subsequent title card reads “around three in the morning”. The young man is roused from his rest by the sound of a door-buzzer ringing (represented visually by a martini shaker being shaken by a set of arms through two holes in a wall). The young woman goes to answer the door and does not return. Another young man dressed in lighter clothing (also played by Pierre Batcheff) arrives in the apartment, gesturing angrily at him. The second young man forces the first one to throw away his nun’s clothing and then makes him stand against a wall.

The subsequent title card reads “Sixteen years ago.” We see the second young man from the front for the first time as he admires the art supplies and books on the table near the wall and forces the first young man to hold two of the books as he stares at the wall. The first young man eventually shoots the second young man when the books abruptly turn into pistols. The second young man, now in a meadow, dies while swiping at a nude figure which suddenly disappears into thin air. A group of men come and carry his corpse away.

The young woman returns to the apartment and sees a death head moth. The first young man sneers at her as she retreats and wipes his mouth off his face with his hand. The young woman very nervously applies some lipstick in response. Subsequently the first young man makes the young woman’s armpit hair attach itself to where his mouth would be on his face through gestures. The young woman looks at the first young man with disgust, and leaves the apartment sticking her tongue out at him.

As she exits her apartment, the street is replaced by a coastal beach, where the young woman meets a third man with whom she walks arm in arm. He shows her the time on his watch and they walk near the rocks, where they find the remnants of the first young man’s nun’s clothing and the box. They seem to walk away clutching each other happily and make romantic gestures in a long tracking shot. However, the film abruptly cuts to the final shot with a title card reading “In Spring,” showing the couple buried in sand up to their elbows.

SURREALISM

Surrealism was a break from the avante-garde movement of European Dadaism in 1933, as Andre Breton developed an international movement titled Surrealism that had several distinct differences to Dadaism. Instead of randomness, chance and anarchy, Surrealism relied on the theories of Sigmund Freud and of the conscious and unconscious mind. Psychoanalysis was also explored which appealed to a language of dreams that critiqued social and moral repression within society. It used cinema as a means to tap into the unconscious mind without intervention of conscious thought and revolution, thinking and experiencing moments through fusion of the real and the surreal.

In his 2006 book Surrealism and Cinema, Michael Richardson argues that surrealist works cannot be defined by style or form, but rather as results of the practice of surrealism. Richardson writes: “Surrealists are not concerned with conjuring up some magic world that can be defined as ‘surreal’. Their interest is almost exclusively in exploring the conjunctions, the points of contact, between different realms of existence. Surrealism is always about departures rather than arrivals.” Rather than a fixed aesthetic, Richardson defines surrealism as “a shifting point of magnetism around which the collective activity of the surrealists revolves.”

Surrealism draws upon irrational imagery and the subconscious mind. Surrealists should not, however, be mistaken as whimsical or incapable of logical thought; rather, most Surrealists promote themselves as revolutionaries. Surrealist works cannot be defined by style or form, but rather as results of the practice of surrealism. Rather than a fixed aesthetic, surrealism can be defined as an ever-shifting art form.

Surrealism was one of the first literary and artistic movements to become seriously associated with cinema, even though it still is a movement that is largely neglected by film critics and historians. The foundations of the surrealism movement coincided with the birth of motion pictures, and the Surrealists who participated in the movement were among the first generation to have grown up with film as a part of daily life.

Surrealism was one of the first literary and artistic movements to become seriously associated with cinema, even though it still is a movement that is largely neglected by film critics and historians. The foundations of the surrealism movement coincided with the birth of motion pictures, and the Surrealists who participated in the movement were among the first generation to have grown up with film as a part of daily life.

Breton himself, even before the launching of the movement, possessed an avid interest in film: while serving in the First World War, he was stationed in Nantes and, during his spare time, would frequent the movie houses with a superior named Jacques Vaché. According to Breton, he and Vaché ignored movie titles at times, preferring to drop in at any given moment and view the films without any foreknowledge. When the two grew bored, they left and visited the next theater. Breton’s movie-going habits supplied him with a stream of images with no constructed order about them in which he could juxtapose the images of one film with those of another, and from the experience craft his own interpretation.

Referring to his experiences with Vaché, he once remarked, “I think what we valued most in it, to the point of taking no interest in anything else, was its power to disorient.” Breton believed that film could help one abstract himself from “real life” whenever he felt like it. Serials, which often contained cliffhanger effects and hints of “other worldliness,” were attractive to early Surrealists. Examples include Houdini’s daredevil deeds and the escapades of Musidora and Pearl White in detective stories.

What endeared Surrealists most to the genre was its ability to evoke and sustain a sense of mystery and suspense in viewers. The Surrealists saw in film a medium which nullified reality’s boundaries. Film critic René Gardies wrote in 1968, “Now the cinema is, quite naturally, the privileged instrument for derealising the world. Its technical resources… allied with its photo-magic, provide the alchemical tools for transforming reality.”

Surrealist artists were interested in cinema as a medium for expression. As cinema continued to develop in the 1920s, many Surrealists saw in it an opportunity to portray the ridiculous as rational. Cinema provided more convincing illusions than its closest rival, theatre, and the tendency for Surrealists to express themselves through film was a sign of their confidence in the adaptability of cinema to Surrealism’s goals and requirements. They were the first to take seriously the resemblance between film’s imaginary images and those of dreams and the unconscious. Director Luis Bunuel said, “The film seems to be the involuntary imitation of the dream.”

Surrealist filmmakers sought to re-define human awareness of reality by illustrating that the “real” was little more than what was perceived as real; that reality was subject to no limits beyond those mankind imposed upon it.Breton once compared the experience of Surrealist literature to “the point at which the waking state joins sleep.” His analogy helps to explain the advantage of cinema over books in facilitating the kind of release Surrealists sought from their daily pressures. The modernity of film was appealing to as well.

Critics have debated whether “Surrealist film” constitutes a distinct genre because recognition of a cinematographic genre involves the ability to cite many works which share thematic, formal, and stylistic traits. To refer to Surrealism as a genre is to imply that there is repetition of elements and a recognizable, “generic formula” which describes their makeup. Several critics have argued that, due to Surrealism’s use of the irrational and on non-sequitur, it is impossible for Surrealist films to constitute a genre.While there are numerous films which are true expressions of the movement, many other films which have been classified as Surrealist simply contain Surrealist fragments. Rather than “Surrealist film” the more accurate term for such works may be “Surrealism in film.”

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

Un Chien Andalou was one of the first films that was made on a shoestring budget, shot with a 35mm handmade camera and made without the need of studio financing with a running time of only 17 minutes. In a lot of ways Bunuel and Dali were the ancestors of the great American independent director John Cassavetes. Bunuel was a young ambitious Spaniard who unfortunately was fired when insulting the great director Abel Gance while working on one of his films in Paris. Bunuel ended up spending a few days with Dali a fellow Spaniard and one day at a restaurant Bunuel told Dali about a dream in which a cloud sliced the moon in half “like a razor blade slicing through an eye”. Dali responded with his own dream which involved a hand crawling with ants. Excitedly, Bunuel declared: “There’s the film, let’s go and make it. They were fascinated by what the psyche could create, and decided to write a script based on the concept of suppressed human emotions. The film only took a period of 10 days shooting in Le Havre and Paris at the Billancourt studios, as Bunuel borrowed some of the films needed budget from his very own mother.

In deliberate contrast to the approach taken by Jean Epstein and his peers, which was to never leave anything in their work to chance, with every aesthetic decision having a rational explanation and fitting clearly into the whole, Buñuel made clear throughout his writings that, between Dali and himself, the only rule for the writing of the script was: “No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.” He also stated: “We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why. Nothing, in the film, symbolizes anything. The only method of investigation of the symbols would be, perhaps, psychoanalysis.”

The shocking images in Un Chien Andalou include the moon, a calf’s eye and a razor, a hand with ants, a transvestite on a bicycle, a hairy armpit, a severed hand being poked with a stick, a death moth, a sexual assault, a woman protecting herself with a tennis racket, an attempted rapist pulling two grand pianos with dead donkeys and priests on top of it, death from a gunshot, and two living statues in sand from the torso up, are just many of the strange images that Bunuel and Dali created up on the screen. Explaining to someone the plot of Un Chien Andalou can be as difficult and frustrating as explaining to someone the plot of a David Lynch film. All one can really do when discussing Un Chien Andalou is simply list its shots because there is no real storyline to link any of the images and a way to really interpret any of their meanings. And yet, we try to link these images anyway, finding some form of answer to what these images mean. There has been countless analysts that applied sexual Freudian, Marxist and Jungian themes to the film, and I can picture Bunuel laughing at them all.

Similar to watching a film like Meshes of the Afternoon directed by the wife and husband team of Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, I believe Un Chien Andalou makes us realize how we as an audience have been programmed and trained to find a symbolic meaning and connection to anything, even with things that are clearly not there. Why is it natural for us to create some form of link or connection to an image that comes before or after another image? For instance we automatically assume that the man pulling the two grand pianos is doing it out of sexual frustration because in the sequence before that one a woman rejected his sexual advances. Why do we automatically assume these things, just because one sequence was edited before or after a completely different sequence and what does that say about how he process our thoughts and ideas? This is what I believe Bunuel is getting at. We naturally can create connections to any separate image or meaning and create any form of explanation that suits us best. While watching Un Chien Andalou it is useful to watch ourselves and how he systematically process certain pieces of information throughout a story as critic Roger Ebert points out: “We assume it is the “story” of the people in the film, these men, these women, these events. But what if the people are not protagonists but merely models, simply actors hired to represent people performing certain actions? We know that the car at the auto show does not belong to (and was not designed or built by) the model in the bathing suit who points to it. Bunuel might argue that his actors have a similar relationship to the events surrounding them.” Luis Bunuel is one of the greatest filmmakers in the world and he has always been considered one of the most cynical of all directors, an artist who liked to point out the absurdities of people and of human nature through his sardonic dry humor. Luis Bunuel made another surrealist film a year later titled L’Age d’Or, which was read to be an attack on Catholicism, and thus, added an even larger scandal than Un Chien Andalou. The right-wing press criticized the film and the police placed a ban on it that lasted 50 years for its unconscious associations to sex and religion. Un Chien Andalou is the type of film that assaults our visions and senses creating a slightly disturbing and maddening film. Many audiences believe that the film serves no real purpose, and yet how much purpose is there when we see movies anyway? Like most of Bunuel’s later films there is humor brewing throughout its abstract story and its controversial themes has a willing cheerfulness to want to offend and shock viewers. Many of the images in Un Chien Analou were considered by some to be an attack on the bourgeois society and of religion, morality, animals, death, eroticism and high culture. The logic of dreams are presented as being more subjected than objective and the film in a way mocks the chronology of narrative while also disorientating the viewer with its logic of continuity between scenes. If shock and scandal was what surrealists originally set out to do with Un Chien Analou than they seemed to have achieved, though I doubt today viewers would have a less likely chance of finding the film as offensive and shocking. Un Chien Andalou demonstrates that art and life doesn’t need to be restricted to certain rules and regulations and that art is a subjective experience with all different kinds of interpretations. Bunuel wrote in his autobiography, “Although the surrealists didn’t consider themselves terrorists, they were constantly fighting a society they despised. Their principal weapon wasn’t guns, of course; it was scandal.”

Similar to watching a film like Meshes of the Afternoon directed by the wife and husband team of Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, I believe Un Chien Andalou makes us realize how we as an audience have been programmed and trained to find a symbolic meaning and connection to anything, even with things that are clearly not there. Why is it natural for us to create some form of link or connection to an image that comes before or after another image? For instance we automatically assume that the man pulling the two grand pianos is doing it out of sexual frustration because in the sequence before that one a woman rejected his sexual advances. Why do we automatically assume these things, just because one sequence was edited before or after a completely different sequence and what does that say about how he process our thoughts and ideas? This is what I believe Bunuel is getting at. We naturally can create connections to any separate image or meaning and create any form of explanation that suits us best. While watching Un Chien Andalou it is useful to watch ourselves and how he systematically process certain pieces of information throughout a story as critic Roger Ebert points out: “We assume it is the “story” of the people in the film, these men, these women, these events. But what if the people are not protagonists but merely models, simply actors hired to represent people performing certain actions? We know that the car at the auto show does not belong to (and was not designed or built by) the model in the bathing suit who points to it. Bunuel might argue that his actors have a similar relationship to the events surrounding them.” Luis Bunuel is one of the greatest filmmakers in the world and he has always been considered one of the most cynical of all directors, an artist who liked to point out the absurdities of people and of human nature through his sardonic dry humor. Luis Bunuel made another surrealist film a year later titled L’Age d’Or, which was read to be an attack on Catholicism, and thus, added an even larger scandal than Un Chien Andalou. The right-wing press criticized the film and the police placed a ban on it that lasted 50 years for its unconscious associations to sex and religion. Un Chien Andalou is the type of film that assaults our visions and senses creating a slightly disturbing and maddening film. Many audiences believe that the film serves no real purpose, and yet how much purpose is there when we see movies anyway? Like most of Bunuel’s later films there is humor brewing throughout its abstract story and its controversial themes has a willing cheerfulness to want to offend and shock viewers. Many of the images in Un Chien Analou were considered by some to be an attack on the bourgeois society and of religion, morality, animals, death, eroticism and high culture. The logic of dreams are presented as being more subjected than objective and the film in a way mocks the chronology of narrative while also disorientating the viewer with its logic of continuity between scenes. If shock and scandal was what surrealists originally set out to do with Un Chien Analou than they seemed to have achieved, though I doubt today viewers would have a less likely chance of finding the film as offensive and shocking. Un Chien Andalou demonstrates that art and life doesn’t need to be restricted to certain rules and regulations and that art is a subjective experience with all different kinds of interpretations. Bunuel wrote in his autobiography, “Although the surrealists didn’t consider themselves terrorists, they were constantly fighting a society they despised. Their principal weapon wasn’t guns, of course; it was scandal.”