Ugetsu (1953)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Ugetsu Kenji Mizoguchi” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Akinari Ueda’s Tales of Moonlight and Rain continues to enchant modern readers with its mysterious fantasies. This film is a new refashioning of those fantasies.”

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Ugetsu Kenji Mizoguchi” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Akinari Ueda’s Tales of Moonlight and Rain continues to enchant modern readers with its mysterious fantasies. This film is a new refashioning of those fantasies.”

Legendary Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece Ugetsu is the greatest of all ghost stories and is a cautionary tale on two characters who are consumed by greed and envy. At a violent time of war these two selfish individuals will risk their families lives to pursue their obsessions and ambitions. The films mysterious tone and elegant feel doesn’t try to hide the fact that it is a ghost story and one of the two ghosts that appear in the film is rather quite obvious. The second one isn’t quite so obvious and yet when it is discovered it brings a tragic and profound haunting power to the story. When most people think of the great Japanese directors they usually site Akira Kurosawa as number one and Yasujiro Ozu as number two. Kenji Mizoguchi is usually number three and is less discussed in film circles which is much unfortunate. He was loved by the French critics of Cahiers du cinema which included Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette and they described Mizoguchi as not only the greatest of Japanese masters but high in the ranks of the greatest filmmakers who have ever practiced the art. French critic Jean Douchet has said, “Kenji Mizoguchi: Like Bach, Titian, and Shakespeare, he is the greatest in his art.” The great director Jean-Luc Godard declared him as “The greatest of Japanese filmmakers,” and the New York Times critic Vincent Canby described him as, “one of the great directors of the sound era.” [fsbProduct product_id=’831′ size=’200′ align=’right’] Mizoguchi was famous for the ‘one scene, one shot,’ technique. His style avoids close-ups and instead links the characters to their environment which creates tension and psychological density. Consider a scene in Ugetsu where Lady Wakasa visits Genjuro as he is bathing in an outdoor pool, and as she enters the pool to join him, water splashes over the side and the camera follows the splash into a pan across rippling water that ends with the two of them having a picnic on the grass. Yasujiro Ozu had a similar technique in his films but the difference with Ozu was that he never moved his camera, unlike Mizoguchi which was a more fluid poetic style. Mizoguchi belongs in the same company as some of the greatest directors in the world, like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, John Ford, Orson Welles, Luis Bunuel, Jean Renoir, Andrei Tarkovsky, Alfred Hitchcock, Yasujiro Ozu, Charles Chaplin, Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer and last but not least Akira Kurosawa; who looked up to Mizoguchi as a master.

PLOT/NOTES

Ugetsu opens in a village called Nakanogo along the shore of Lake Biwa in Omi Province in the late 16th century. It revolves around two peasant couples – Genjuro, Miyagi and their son Genichi, Tobei and Ohama – who are uprooted as Shibata Katsuie’s army sweeps through their farming village, Nakanogo. Genjuro, whose business is the manufacture of earthenware pots, takes his wares to nearby Omizo. While packing for one of his trips to Omizo he hears Shibata’s executing spies far off from the village and he realizes he needs to make as much profit as he can in Nagahama before the fighting starts.

He tells his wife, Miyagi “I hear business is booming there since Hashiba’s forces arrived.” His wife asks to come along but Genjuro believes it not safe not knowing what lawless soldiers might do. “Besides, you must stay and take care of little Genichi.” he tells her. He is accompanied on the trip with his friend Tobei who arrives wearing a samurai outfit; with his wife shouting at him from behind. “What a samurai you’ll make! Crazy fool! You can’t even handle a sword. Stick to your trade or you’ll regret it.” But Tobei’s dream is to be a respected and powerful samurai and Genjuro’s dream is to become wealthy.

They then both leave and head for Nagahama, and later that day a respected sage warns Miyagi about her husbands greed. “They’re too greedy for their own good. Quick profits made in chaotic times never last. A little money inflames men’s greed. They’d do better to prepare for the coming war.” Genjuro finally arrives home after being successful and making a lot of money. When Miyagi asks where Tobei is Genjuro says, “He saw a find samurai in town. I tried to stop him but he followed the samurai.”

The film then shows Tobei in Nagahama as he pathetically begs a samurai to be his vessel. “I’ll serve you faithfully unto death!” he shouts. The samurai tells him to get some armor and a spear first if they would ever think of accepting him and Tobei gets thrown out. That evening Genjuro’s wife and son are enjoying expensive food and his wife is enjoying a new kimino he had bought for her. He tells his wife, “money is everything. Without it life is hard and hope dies.” Miyagi warns him that they have to be cautious because of the word around the village that Hashiba’s forces could arrive and attack at any time.

Genjuro says, “nonsense! War’s good for business. Look how much I made!” but his wife tells him he was fortunate once but may not be the next time. Suddenly Tobei arrives home and his wife Ohama is furious at her husband and his behavior shouting at him that he looks like the village beggar. The next few days Miyagi is working long hours making more pottery but he gets frustrated and takes it out on his son who is disrupting his pottery making shouting, “Get him out of here! He’s in the way. What a pest!” Miyagi says, “you’re a different man now. Always so irritable.”

One night Nakanogo is suddenly attacked by soldiers as villagers are screaming, “it’s Shibata’s army! Hurry, run!” Genjuro doesn’t want to leave his kiln because some of them are not finished being cooked. Miyagi says, “hurry, let’s run! It’s too dangerous here. You’ll lose your life for that kiln.” Genjuro says, “if we lose this batch, I won’t get my share of the profits!” Eventually he flees with his family and the four main characters hide out in the woods with several other villagers. During the evening Genjuro runs back to his home risking his life to try to save some of his pottery and his wife follows him.

Suddenly Hashiba troops are walking throughout the area so the two of them hide. After the troops leave, Gejuro comes out and finds his pottery completely finished and unharmed. Genjuro decides to take his pots to a different marketplace, and when Tobei and Ohama arrive they help Genichi and Miyagi unload the pottery into a canoe and the two couples head towards Omizo across the lake to sell the merchandise. In some of the most beautiful shots of the film the canoe appears like a ghost through thick fog as Ohama sings a beautiful and haunting song. “It’s good we went by boat. On foot we’d probably be dead by now.” Miyagi says. Tobei tells the group they will probably reach Omizo by morning and describes how prosperous Omizo is and that it’s also the location of Lord Niwa’s castle. Genjuro says, “you and I will be rich men, and our wives will be wealth women.”

Suddenly out of the thick fog another boat appears. Tobei’s says it’s a ghost of the lake. “No, I’m not a ghost” says the passenger. He tells them he is from Kaizu and that he was attacked by pirates. He warns the group to head back to their homes saying, “Wherever your headed watch out for pirates. If they see you you’ll lose your cargo and your lives.. Watch out for your women.” The passenger suddenly dies and Genjuro and Tobei decide to return their wives to the shore but Tobei’s wife refuses to go and leave her husband. Miyagi begs Genjuro not to leave her, but it is too dangerous for her and their son Genichi to travel along.

They drop Miyagi and Genichi off on the shore as they travel away on the canoe with Genjuro shouting to his wife and child to be patient and they will return wealthy; as Miyagi starts heading back to the village with her son strapped to her back. At the Azuchi market, Genjuro’s pottery sells well. A beautiful noblewoman and her servant come up and offer to buy several pieces of Genjuro’s pottery. The servant says to Genjuro, “We live at Kutsuki Manor. Please deliver them there. We will pay you at that time.”

Tobei sees a group of samurai marching though the town and he’s entranced by their armor and swords. Tobei decides to run off and foolishly spend the profits he made by buying samurai armor. Ohama trying to talk him out of it, calling him a fool and he shouts to her, “Let me go! I’ll be a great samurai next time we meet!” He then abandons her and Ohama soon finds herself lost near the shore in her desperate search for Tobei. Tobei heads to a market and buys armor and a spear while Ohama gets attacked and then raped by a group of soldiers.

After the rape Ohama is ashamed and says out loud to herself, “look whats come of me? Satisfied now, seeing your wife reduced to this? What do you care? You’re so happy to be a samurai. Tobei, you wretched fool!” When Ohama and Tobei don’t return Genjuro asks a man to watch over his stall until they return because he has to deliver merchandise to the customers at Kutsuki mansion. Walking through the market he runs into the noblewoman and the servant once again and they offer to lead him to Kutsuki mansion.

When arriving there and dropping off the bought merchandise he’s about to leave when the servant invites him in saying, “Lady Wakasa is waiting. Daughter of the late Lord Kutsuki. Please step inside.” When inside, Lady Wakasa emerges and asks Genjuro if he is Master Genjuro of Omi province. Genjuro asks her how she knows his name and she says it was from the ceramics at the market and how much she loves his craftsmanship. She tells him her father taught her a certain appreciation for art and she tells him, “I wanted to meet you to ask how you manage to create such beautiful objects.” Genjuro says it’s no secret but it takes years of experience to handle the clay and apply the glaze.

Her servants come in and serve Genjuro food from the cups he himself had molded. “I’m a farmer, so the pottery is just a sideline. But I feel for my creations as if they were my own children. That such a noble lady would look kindly on them is a great honor,” Genjuro admits to her. Lady Wakasa says that his talent must not be hidden away in some poor remote village and he must deepen and enrich his gift. When he asks her how he could do so the servant lady says, “by swearing your love for Lady Wakasa and marrying her at once.” The Kutsuki mansion lies in ruins, and during dinner Genjuro learns that soldiers have attacked the castle and killed all who lived there, except Lady Wakasa and her three servants. He also learns that Lady Wakasa’s father haunts the castle and speaks when ever his daughter is happy. Genjuro is seduced by Lady Wakasa beauty and wealth, and she eventually convinces him to marry her.

Over a long period of time living in Kutsuki Genjuro feels like he is in a paradise. His now new found wife takes care of him and says to him, “from now on you must devote your entire life to me.” One evening she baths him in a bath as the shot then shifts to them near the ocean having a picnic and holding each other on the beach. Genjuro tells her, “Even if you are a ghost or enchantress, I’ll never let you go. I never imagined such pleasures existed.This is exquisite! It’s paradise!”

Meanwhile, the village of Nakanogo is under attack and Miyagi and her son Genichi hide from the violent soldiers who are ravaging her home. They are found by an elderly neighbor who gives them food and hurries the both of them to safety. In the woods, several soldiers desperately search her for food. She fights with the soldiers and is stabbed as Miyagi collapses with her son still clutching her back. In the next scene Tobei witnesses the beheading of a General attacks the soldier who committed the beheading from behind killing him. He then steals the severed head of the general and presents to the commander of the victorious side; telling them he had defeated him.

The commander laughs at Tobei and says, “Who would believe a great warrior like Katsuhige Fuwa would let a mere foot soldier kill him? A lucky find, but you’ll be rewarded all the same. What would you like?” Tobei asks for a horse, armor and vassals and is given them. Tobei later rides into the marketplace on his new horse, eager to return home to show his wife the warrior the public now think he is. However, he visits a brothel to celebrate his recent triumph as his men shout, “Clear the way for Master Tobei!” At the brothel Tobei is admired by everyone as a hero as men ask him if they can drink from his glass for good fortune and also ask of his recent exploits and adventures. Of course he answers by giving pathetic fictional stories on how to become a strong and wise warrior.

A whore suddenly runs out of one of the private rooms trying to stop a customer from not paying and Tobei realizes its his wife Ohama. When she sees her husband she says to him, “so you’re a great man now. Finally became the samurai of your dreams, eh? While you’ve made your way to the top, I’ve made a name for myself too. I bed a different man every night. Some success for a women, isn’t it? Success always comes with a price in suffering. Your wife may be fallen, but your success wipes the slate clean. Be my customer tonight and we’ll celebrate. Buy this fallen woman with the money your exploits earned you!” Tobei pulls her outside and tells her his success means nothing without her and he is sorry. “I’m a defiled woman and your to blame,” she says to him. She then tells him how she has wanted to die so many times but wanted to see him first. Tobei believes he can still restore her honor as she falls to the ground and breaks down to cry. Tobei promises her that he will do all that he can to buy back her honor.

One day in near town Genjuro meets a priest who stops him on the street and says he sees a bad omen. He looks closely at his face and tells him “the shadow of death is upon your face.” He tells Genjuro to follow him back to his place and later that evening the wise man asks Genjuro if he has a home or family. The priest then tells him he must return home at once because if he stays here any longer he will die. When Genjuro tells him he spends his days happily with Lady Wakasa at Kutsuki Manor, the Priest tells him Lady Wakasa is a spirit from the dead. “This love of yours is forbidden. Do you not love your wife and child? Would you forsake your life and abandon them too?” he asks. Genjuro believes what the Priest is saying is nonsense but before leaving the priest asks if he can exorcise the ghost for him.

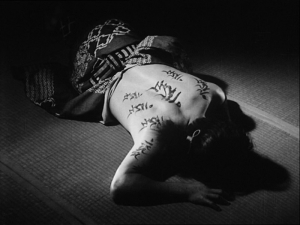

Genjuro returns to the Kutsuki mansion and Lady Wakasa notices Genjuro looks troubled. Genjuro finally reveals to her that he has a wife and child and left them in the chaos of war and he must return. Lady Wakasa tells him he can’t leave because he is hers forever but when trying to touch Genjuro she suddenly backs away because of what he has on his skin which are Buddhist prayers on his body. Lady Wakasa’s servant yells, “Why did you wed her if you were already married? Wipe off those Sanskrit characters, those prayers to Buddha, that curse, or we will never forgive you! Lady Wakasa departed this world, without ever having known love. I wanted my lady to enjoy fully the pleasures of a woman’s life, so we returned to wander this world. Our hopes were fulfilled. She met a good man like you and found a love that happens once in a lifetime. Now, when she has at last found joy, you speak of returning home never to see each other again.”.

Genjuro reaches for a sword, throws himself out of the manor, and passes out. The next day, he is awakened by soldiers. They accuse him of stealing the sword, but he denies it, saying it is from the Kutsuki mansion. The soldiers laugh at him, saying the Kutsuki mansion was burned down over a month ago. After the soldiers take all of Genjurop’s money that they believe he stole, Genjuro looks up and finds the ruined mansion he has lived in is nothing more than a pile of burnt wood.

Genjuro returns to his village and when he goes into his home, in one of the most magnificent shots in the film the camera does a 360 arc throughout his empty hut and when it comes back around it finds his wife Miyagi now in the frame by a fire finishing his pottery; in which we as an audience are relieved to find her alive. When Miyagi sees her husband she embraces him and then wakes up their son Genichi. Genjuro tells his family, “I wanted to bring back nice presents, but this is all I have. I made a terrible mistake! I realize now how right you were… My mind was warped.”

Miyagi tells him to not say another word because he has come back to them safe and sound and she gives him a drink of saké and puts his son Genichi back to bed. “I haven’t had a moments’ peace since I left but I’m home at last,” Genjuro pleasantly says as he slowly falls asleep. In a beautiful quite moment Miyagi tenderly covers her husband up with a blanket as she then lights a candle and finishes doing her domestic work as daylight slowly arrives.

That next morning the village chief knocks on the door looking for Genichi and is surprised to see Genjuro. The village chief is relieved to find Genichi at Genjuro’s house saying, “There’s the boy. I was so worried not knowing where he’d gone. The boy must have heard you were back.” Genjuro happily calls out for his wife and the village chief is bewildered asking if Genjuro is dreaming.

The village chief then tells Genjuro, “Miyagi was killed by soldiers of the defeated army. She’d have been so happy to see you back safe and sound. Poor thing. Merciful Buddha. Ever since she died I’ve been looking after your boy in my house. I was afraid when he disappeared last night. The bond between parent and child is strong indeed. But how could he have known you’d returned?”

The village chief then tells Genjuro, “Miyagi was killed by soldiers of the defeated army. She’d have been so happy to see you back safe and sound. Poor thing. Merciful Buddha. Ever since she died I’ve been looking after your boy in my house. I was afraid when he disappeared last night. The bond between parent and child is strong indeed. But how could he have known you’d returned?”

The last shot of the film shows Genjuro and his son Genichi spending time together as Genjuro is hard at his work on his potter’s wheel, doing what he loves, while he continues to hear the ghost of Miyagi’s voice who now approves of the man he has now become.

ANALYZE

Often appearing on lists of the ten greatest films of all time, called one of the most beautiful films ever made, or the most masterful work of Japanese cinema, Ugetsu comes to us awash in superlatives. No less acclaimed has been its maker, Kenji Mizoguchi: “Like Bach, Titian, and Shakespeare, he is the greatest in his art,” enthused the French critic Jean Douchet; and not far behind were Jean-Luc Godard, who declared him “the greatest of Japanese filmmakers, or quite simply one of the greatest of filmmakers,” and the New York Times critic Vincent Canby, who extolled him as “one of the great directors of the sound era.” In other words, Mizoguchi belongs in the same exalted company as Jean Renoir, Orson Welles, Carl Dreyer, Alfred Hitchcock, Max Ophüls, Sergei Eisenstein, Robert Bresson, and Akira Kurosawa (who looked up to the older man as his master). This near unanimous reverence for both Ugetsu and Mizoguchi among world filmmakers and critics may be puzzling to the American movie-going public, for whom both names remain relatively unfamiliar. In order to understand what the fuss is about, we may need to take a step back from these superlatives, or at least put them in context.

Mizoguchi (1898–1956) began his career in the silent era and made dozens of fluent, entertaining studio films before arriving at his lyrical, rigorous visual style and patented tragic humanism, around the age of forty. His first masterworks were a pair of bitterly realistic films, made in 1936, on the subject of modern women’s struggles, Sisters of the Gion and Osaka Elegy. These breakthroughs led to the classic Story of the Last Chrysanthemum (1939), set in the Meiji era, about a Kabuki actor who stubbornly hones his craft with the aid of his all-too-sacrificing lover. In this film, Mizoguchi perfected his signature “flowing scroll,” “one shot–one scene” style of long-duration takes, which, by keeping the camera well back, avoiding close-ups, and linking the characters to their environment, generated hypnotic tension and psychological density. During the early 1940s, the director was hampered by the Japanese studios’ war propaganda effort, though he did make a stately, two-part version of The 47 Ronin. After the war ended, he turned to a series of intense pictures advocating progressive, democratizing ideals, which fell in with the occupation’s values while wobbling aesthetically between subtle refinement and hammy melodrama.

Then, in the 1950s, he regained his touch and created those sublimely flowing, harrowing masterpieces that represent the pinnacle of his directorial achievement: The Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), A Story from Chikamatsu (1954), Sansho the Bailiff (1954), New Tales of the Taira Clan (1955), and Street of Shame (1956). Except for the last, these pictures were all set in earlier times: Mizoguchi, drawing on Saikaku, Chikamatsu, and other classical writers, had become a specialist in the past, reinterpreting national history as much as, say, John Ford, and insisting, like Luchino Visconti, on accurate historical detail, borrowing props, kimonos, suits of armor from museums and private collectors. He attributed his fascination with traditional Japanese culture partly to his own relocation from Tokyo to the Kyoto area.

No doubt, some of Mizoguchi’s belated international renown (he won Venice Film Festival prizes three years in a row, for The Life of Oharu, Ugetsu, and Sansho the Bailiff) had to do with satisfying the West’s taste for an exoticized, traditional Japan. But he also fit the profile of the brilliant, uncompromising auteur (a perfectionist who would demand hundreds of retakes and move a house several feet to improve the vista). Also, his moving-camera, long-shot aesthetic exemplified the Bazinian mise-en-scène aesthetic that the young Cahiers du cinéma critics were championing, and anticipated the widescreen filmmaking of Michelangelo Antonioni, Miklos Jansco, Nicholas Ray, and others.

Mizoguchi engaged with the past not to recapture nostalgically some lost model of serenity but, if anything, to reveal the opposite. In preparing Ugetsu, he was drawn to sixteenth-century chronicles about civil wars and their effect on the common people. As a starting point, he and screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda adapted two tales from an eighteenth-century collection of ghost stories, Akinari Ueda’s Ugetsu monogatori (Tales of Moonlight and Rain), retaining much of the imagery while altering elements of the stories. The perennially dissatisfied Mizoguchi stressed in his notes to the long-suffering Yoda: “The feeling of wartime must be apparent in the attitude of every character. The violence of war unleashed by those in power on a pretext of the national good must overwhelm the common people with suffering—moral and physical. Yet the commoners, even under these conditions, must continue to live and eat. This theme is what I especially want to emphasize here. How should I do it?”

Ugetsu ended up concentrating on two couples. The main pair are a poor potter, Genjuro, who is eager to make war profits by selling his wares to the competing armies, and his devoted wife, Miyagi, who would prefer he stay at home with their little boy and not take chances on the road. (The acting between these two is beyond exquisite: the brooding Masayuki Mori, who played Genjuro, and the incomparable Kinuyo Tanaka, cast as his wife, were two of Japan’s greatest actors, though filmed by Mizoguchi in a determinedly unglamorous, non-movie-star way.) The second couple are a peasant, Tobei, who assists Genjuro in his trade but would rather become a samurai, and his shrewish wife, Ohama, who ridicules her husband’s fantasies of military glory. In this “gender tragedy,” if you will, the men pursue their aggressive dreams, bringing havoc on themselves and their wives. Still, the point is underlined that these men don’t want to escape their wives; they only want to triumph in the larger world, so as to return to their wives made into bigger men by boast-worthy adventures and costly presents.

Are we to take it, then, that the moral of the film is: better stay at home, cultivate your garden, nose to the grindstone? No. Mizoguchi’s viewpoint is not cautionary but realistic: this is the way human beings are, never satisfied; everything changes, life is suffering, one cannot avoid one’s fate. If they had stayed home, they might just as easily have been killed by pillaging soldiers. The fact that they chose to leave gives us a plot, and some ineffably lovely, heartbreaking sequences.

The celebrated Lake Biwa episode, where the two couples come upon a phantom boat in the mists, is surely one of the most lyrical anywhere in cinema. Edited to create a stunningly uncanny mood, it also prepares us for the supernatural elements that follow. The dying sailor on the boat is not a ghost, though the travelers at first take him for one; he warns them, particularly the women, to beware of attacking pirates, another ominous foreshadowing.

It is the movie’s supreme balancing act to be able to move seamlessly between the realistic and the otherworldly. Mizoguchi achieves this feat by varying the direction between a sober, almost documentary, long-distance view of mayhem and several carefully choreographed set pieces, such as the phantom ship. A particularly wrenching scene involves the potter taking leave of his wife and son: the pattern of cuts between the husband on the boat, moving off, and the wife running along the shore, waving, comes to concentrate more and more on her stricken, prescient awareness of what lies ahead (he, still having no idea, does not deserve our scrutiny). Later, the bestial behavior of the hungry, marauding soldiers coming upon the potter’s wife is shot from above, with a detached inevitability that makes the savagery more matter-of-fact, the soldiers pathetically staggering about in the background (an effect that must have inspired Godard and François Truffaut in their distanced shoot-outs).

Mizoguchi’s artistry reaches its pinnacle in the eerie sequences between Genjuro and Lady Wakasa. Bolerolike music underscores the giddy progression by which the humble potter is lured to the noble-woman’s house, is seduced by her, and experiences the ecstasy of paradise, only to learn that he has fallen in love with a ghost. Machiko Kyo, one of Japan’s screen goddesses, plays Lady Wakasa with white makeup that resembles a Noh mask and slithery movements along the floor like those of a woman fox. Interestingly, she seduces Genjuro as much with her flattery of his pottery as with her dangerous beauty. Previously, we have seen Genjuro (a surrogate for the director?) obsessed with his pot making, but it is only when Lady Wakasa compliments him on these objects, which she has been collecting, that he appreciates himself in this light, making the telling comment, “The value of people and things truly depends on their setting.” In so doing, he embraces Mizoguchian aesthetics, while she raises him from artisan to artist, putting them on a more equal social footing. Their love affair plays out in the rectangular castle of shoji-screened rooms, around an open courtyard, an architectural setting much more aristocratically formal than the village sequences. There is also a breathtakingly audacious shot that tracks from night to day, starting with the two of them in a bath together, then moving across a dissolve and an open field, to pick them up picnicking and disporting in the garden.

As Mizoguchi’s great cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, stated in a 1992 interview, they used a crane 70 percent of the time in filming Ugetsu. The camera, almost constantly moving—not only laterally but vertically—conveys the instability of a world where ghosts come and go, life and death flow simultaneously into each other, and everything is, finally, transient, subject to betrayal. At her wedding to Genjuro, Lady Wakasa sings: “The finest silk / Of choicest hue / May change and fade away / As would my life / Beloved one / If thou shouldst prove untrue.” The camera’s viewpoint is always emotionally significant: we look down from above as Lady Wakasa leans over Genjuro to seduce him, as though to convey his fear and desire, while we are practically in the mud with Tobei as he crawls along on his belly, before witnessing his big break—the enemy general’s suicidal beheading, for which he will take credit.

Just as the camera’s image field keeps changing (without ever losing its elegantly apt compositional sense), so too do our sympathies and moral judgments shift from character to character. No doubt, Genjuro is right to want to escape the clutches of his ghostly mistress, yet she has given him nothing but happiness and is justified in feeling betrayed by him. Tobei is something of a clown, a buffoon, yet his pain is real enough when, puffed up with samurai vanity, he finds his wife working in a brothel. The complex camera movement that follows Ohama from berating a customer to stumbling upon the open-jawed Tobei, and the ensuing passage in which she struggles between anger, shame, and happiness at being reunited with him, demonstrate the way that this director’s compassionate, if bitter, moral vision and his choice of camera angle reinforce each other. Mizoguchi’s formalism and humanism are part of a single unified expression.

Perhaps the most striking instance of this transcendent tenderness comes toward the end, when Genjuro returns home from his journey, looking for his wife: the camera inscribes a 360-degree arc around the hut, resting at last on the patient, tranquil Miyagi, who we had assumed was dead, having seen her speared earlier. We are relieved, as is Genjuro, to see her preparing a homecoming meal for her husband and mending his kimono while he sleeps. On awaking, he discovers that his wife is indeed dead; it appears he has again been taken in by a woman ghost. The sole consolation is that we (and presumably Genjuro) continue to hear the ghost of Miyaki’s voice, as she watches her husband approvingly at his potter’s wheel, noting that he has finally become the man of her ideals, though admitting that it is a pity they no longer occupy the same world. One might say that Mizoguchi’s detached, accepting eye also resembles that of a ghost, looking down on mortal confusions, ambitions, vanities, and regrets. While all appearances are transitory and unstable in his world, there is also a powerfully anchoring stillness at its core, a spiritual strength no less than a virtuoso artistic focus. The periodic chants of the monks, the droning and the bells, the Buddhist sutras on Genjuro’s back, the landscapes surrounding human need, allude to this unchanging reality side by side with, or underneath, the restlessly mutable. Rooted in historical particulars, Ugetsu is a timeless masterpiece.

-Phillip Lopate

The more times I watch Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu, the more powerful it becomes and the more I greatly admire. This is a very hypotonic fable about the lust for greed and envy and yet the context of the films story is very gritty and based in realism. It’s unfortunate that Mizoguchi isn’t as known in the west as Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu because his films are just as important, poetic and say just as much about Japanese culture then the other two directors. Mizoguchi began his career in the early silent era and most of his early themes were the problems and issues women had to deal with in society. After successful films like The 47 Ronin and Osaka Elegy in the early 30’s to the late 40’s he started making a name for himself under the Daiei production company.

It was in the 50’s where Mizoguchi made most of his legendary masterpieces including The Life of Oharu, which tells a story of a middle-aged prostitute in 17th century Japan and how she got to where she is, The Crucified Lovers, which is about a wealthy scroll-maker who is falsely accused of having an affair with his best worker, and then there is one of my favorites, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum which tells the story of the son of a famous actor, who is openly praised for his performance on the stage just due to his name. Street of Shame is another classic which tell the various stories of prostitutes in a brothel. His film Sansho the Bailiff is considered beside Ugetsu as one of his best films and usually is cited as one of the greatest films in the world. It tells the story of a compassionate governor who is sent into exile and his wife and children try to join him, but are taking into slavery camps and suffer beatings and oppression. Sansho the Bailiff is one of my favorite films and is on my top 10 films of all time.

Like all the great masters Mizoguchi had his own personal themes that he relished on in each film he made. His themes mostly focused on poverty, obsession of becoming wealthy and a women’s place in Japanese society. He is known for the elegance of his compositions and the tact of his camera movement which show his technique of ‘one scene, one shot.’ Ugetsu came about when Mitzoguchi and screenwriter Yoshikata Yoda adapted two tales from an eighteenth century collection of ghost stories, Akinari Ueda’s (Tales of Moonlight and Rain) keeping much of the imagery but altering several elements of the story. Mizoguchi stressed in his notes to Yoda: “The feeling of wartime must be apparent in the attitude of every character. The violence of war unleashed by those in power on a pretext of the national good must overwhelm the common people with suffering-moral and physical. Yet the commoners, even under these conditions, must continue to live and eat. This theme is what I especially want to emphasize here. How should we do it?”

The story of Ugetsu eventually ended up concentrating on two peasant couples. The poor potter maker Genjuro is eager to make war profits by selling his pottery to the competing armies and his devoted wife believes it’s not safe to take chances during wartime and for him to stay home with her and their son. The second couple are much more complicated. Tobei is a man who helps Genjuro with his trade but is rather more interested in being a samurai. His wife Ohama ridicules him and insults him on his macho fantasy of becoming a samurai and because of this it brings chaos in their lives. These men don’t necessarily want to leave their wives and they are not unhappy in their marriage; they just want to make it as successful and important men so they can return to their wifes as respectable gentlemen. Later in the story when Genjuro is lured in Lady Wakasa’s house and is seduced by her, I believe he got seduced more by his flattery of her love of his pottery work then of her beauty and wealth. He takes much pride in his work and for a woman to relinquish so much admiration to a man’s work is one of the reasons that Genjuro fell under her spell. I understand Genjuro’s right in wanting to leave Lady Wakasa’s mansion and yet she has giving him everything and is justified in feeling betrayed by him. Tobei’s character is more of a clown and a moronic buffoon and in many ways is the dark comedy in the story. And yet when he recognizes his wife as one of the prostitutes in the brothel later in the film you can feel his pain. She of course is justified in feeling her shame and anger towards her husband for everything she has put up with being married to him; and yet we know these two will get through whatever tough times they endured and will together prevail in the end. Like the ending of Sansho the Bailiff, Mizoguchi’s ending of Ugetsu is one of the most cinematically beautiful endings in the cinema and cannot be described in words. In one of the most magnificent camera shots that I have ever seen, (and I still can’t figure out how Mizoguchi had accomplished this) the camera does a 360 arc throughout his empty hut and when it comes back around it miraculously finds Genjuro’s wife Miyagi now in the frame by a fire finishing his pottery. Ugetsu when released won the Silver Lion Award for Best Direction at the Venice Film Festival in 1953. The film appeared in Sight and Sound magazine’s top ten critics poll of the greatest movies ever made, which is held once every decade, in 1962 and 1972. In 2000, The Village Voice newspaper ranked Ugetsu at #29 on their list of the 100 best films of the 20th century. The end of Ugetsu might seem like a complete tragedy and yet when looking at it closer, it is not. The last shot of the film shows Genjuro and his son Genichi spending time together as Genjuro is hard at his work on his potter’s wheel doing what he loves doing. He continues to hear the ghost of his wife approving of the man he has become, and yet it is sad they can no longer occupy the same world. But her spirit will always be with Genjuro and hopefully in time he can prosper like he originally wanted which gives this film a spiritual like strength and makes it the timeless masterpiece it is.

The story of Ugetsu eventually ended up concentrating on two peasant couples. The poor potter maker Genjuro is eager to make war profits by selling his pottery to the competing armies and his devoted wife believes it’s not safe to take chances during wartime and for him to stay home with her and their son. The second couple are much more complicated. Tobei is a man who helps Genjuro with his trade but is rather more interested in being a samurai. His wife Ohama ridicules him and insults him on his macho fantasy of becoming a samurai and because of this it brings chaos in their lives. These men don’t necessarily want to leave their wives and they are not unhappy in their marriage; they just want to make it as successful and important men so they can return to their wifes as respectable gentlemen. Later in the story when Genjuro is lured in Lady Wakasa’s house and is seduced by her, I believe he got seduced more by his flattery of her love of his pottery work then of her beauty and wealth. He takes much pride in his work and for a woman to relinquish so much admiration to a man’s work is one of the reasons that Genjuro fell under her spell. I understand Genjuro’s right in wanting to leave Lady Wakasa’s mansion and yet she has giving him everything and is justified in feeling betrayed by him. Tobei’s character is more of a clown and a moronic buffoon and in many ways is the dark comedy in the story. And yet when he recognizes his wife as one of the prostitutes in the brothel later in the film you can feel his pain. She of course is justified in feeling her shame and anger towards her husband for everything she has put up with being married to him; and yet we know these two will get through whatever tough times they endured and will together prevail in the end. Like the ending of Sansho the Bailiff, Mizoguchi’s ending of Ugetsu is one of the most cinematically beautiful endings in the cinema and cannot be described in words. In one of the most magnificent camera shots that I have ever seen, (and I still can’t figure out how Mizoguchi had accomplished this) the camera does a 360 arc throughout his empty hut and when it comes back around it miraculously finds Genjuro’s wife Miyagi now in the frame by a fire finishing his pottery. Ugetsu when released won the Silver Lion Award for Best Direction at the Venice Film Festival in 1953. The film appeared in Sight and Sound magazine’s top ten critics poll of the greatest movies ever made, which is held once every decade, in 1962 and 1972. In 2000, The Village Voice newspaper ranked Ugetsu at #29 on their list of the 100 best films of the 20th century. The end of Ugetsu might seem like a complete tragedy and yet when looking at it closer, it is not. The last shot of the film shows Genjuro and his son Genichi spending time together as Genjuro is hard at his work on his potter’s wheel doing what he loves doing. He continues to hear the ghost of his wife approving of the man he has become, and yet it is sad they can no longer occupy the same world. But her spirit will always be with Genjuro and hopefully in time he can prosper like he originally wanted which gives this film a spiritual like strength and makes it the timeless masterpiece it is.