400 Blows, The (1959)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”400 Blows Francois Truffaut” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Dedicated to the memory of Andre Bazin.”

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”400 Blows Francois Truffaut” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Dedicated to the memory of Andre Bazin.”

French director François Truffaut’s masterpiece The 400 Blows is the most touching and greatest of all films about childhood adolescence. Inspired by Truffaut’s own early life, it is one of the great coming of age stories that portrays a boy growing up in Paris and apparently dashing headlong into a life of crime. Told through the eyes of young Antoine Doinel, the film unsentimentally re-creates the personal trials in Antoine’s life, as his distant parents and oppressive teacher can’t seem to reach him. The 400 Blows is one of my top ten films of all time and is the first of many films that started a influential movement called The French New Wave, which was considered a certain European art form during the late 50s and 60s. The French New Wave was a movement led by a group of young filmmakers that included Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette who were connected to the magazine ‘Cahiers du cinema’. The idea of The French New Wave film was that it should seem personal and freewheeling, where the directors often chose to shoot on location, using natural lighting and often using hand-held cameras which added to the experimental feel of the films. A lot of these styles were used in one of Jean-Luc-Godard’s greatest and most famous film of The New Wave, Breathless. Key themes explored in the French New Wave include breaking the distinguishing boundaries of realism, and the idea of exploring the relationships between men and women. François Truffaut’s has said again and again, that the cinema saved his life. Similar to the character of Antoine Doinel, Truffaut spent a lot of his free time ditching school and escaping to the movies, and when the direction in his life began to spiral out of control, he himself had run away from home at the age of eleven. The 400 Blows was Truffaut’s first feature, and we can feel that the film is personal to Truffaut, a film that comes straight from his heart. [fsbProduct product_id=’726′ size=’200′ align=’right’]The beginning of the film is dedicated to his mentor Andre Bazin, who was the legendary French film critic who took the troubled youth under his wing at a time most needed. When Truffaut was at the crossroads of his life which divided a life as a film director or a life in trouble, the encouragement of Bazin shaped Truffaut into the great film critic he is known for today, and Truffaut directed The 400 Blows on his 27th birthday. Film critic Roger Ebert said, “If the New Wave marks the dividing point between classic and modern cinema (and many think it does), then Truffaut is likely the most beloved of modern directors, the one whose films resonated with the deepest, richest love of movie-making.” François Truffaut loved the character of Antoine Doinel so much in fact that he decided to use him again, and again, and followed Antoine for over 20 years using actor Jean-Pierre Leaud in four more films. In a short film called Antoine and Colette, Antoine is sixteen years old; in Stolen Kisses, he is twenty-two; in Bed and Board, he is twenty-four; and in Love on the Run, he is thirty-three. Those films are all great touching stories, but The 400 Blows was in a class of its own. It was revolutionary in its storytelling, and it was raw and real. It was a film that made us feel what it was like to have our innocence, and then to have it stripped away from us once again.

PLOT/NOTES

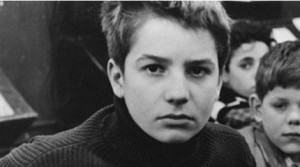

Antoine Doinel is a confused mischievous 12-year-old boy growing up in Paris in the 1950s living with his mother and stepfather. In the first shot of the film you see a bunch of students secretly passing around a nude calendar in class from student to student and when it finally reaches Antoine you hear is teacher say, “Doinel, bring me that. Nice…go stand in the corner.” Antoine stands in the corner of the classroom and when recess begins the teacher tells Antoine he can’t attend recess. During recess Antoine decides to write on the classroom wall, and when the students come back inside from recess they all crowd around to see what he wrote. The teacher sees this and grabs Antoine saying, “We have a young Juvenal in our class.”

Punishment for that Antoine is given an extra homework assignment to write a paper on “why he defaced the classroom wall’ and tells Antoine, “Now, Doinel, go get some water and erase those insanities, or I’ll make you lick the wall, my friend.” There’s an interesting moment in the classroom scene that Truffaut added while his teacher is writing up on the chalkboard. The camera is focused on one of the students who is having trouble keeping up with the teacher because he’s always smudging his pen, so he keeps ripping out paper after paper from his notebook until he realizes he is completely out of paper.

When school lets out Antoine and his best friend Rene walk home together with Antoine saying, “I’ll never finish my homework tonight.” He then tells Rene how he is going to one day smash one of the students in the face because he always squeals on him. School isn’t the best for Antoine and it’s not much easier for him at home either because his mother isn’t very nice to Antoine. She is very stern, disconnected and gets frustrated with him very easily, unlike his stepfather who is more easy-going, and friendly.

When Antoine arrives home it’s an empty apartment. You watch him steal some of his parents cash from their secret stash compartment, then you see him go into his mother’s bedroom. He uses her hairbrush, smells her perfume and even tries her eye-curler. Then he sets the dinner table knowing his parents will be soon returning home. It’s these quiet character moments that make this film as touching and great as it is. When his mother comes home she coldly orders Antoine to go out and get flour. When he returns back his stepfather is there so Antoine asks his stepfather for 1,000 francs. His stepfather replies, “Which means you’re hoping for 500, meaning you really need 300, so hears a hundred.”

The next morning when Antoine is getting ready for school he suddenly remembers the paper he was supposed to write on defacing the classroom wall. He and Rene both decide to not go to school and instead ditch and go to the movies. After leaving the cinema the two decide to head to the amusement park and there’s a memorable scene of them riding on a Wheel-spinning ride, where Antoine stands against a wall, and the ride spins at fast rate, forcing Antoine and the other adventurers to rise in the air and stick to the wall. Later on that very day Antoine catches his mother in the street with another man, and she catches him too. Of course he knows he’s safe and that his mother wouldn’t dare say anything to his stepfather of him skipping school, because of what he caught her doing as well. Rene says to him, “You’ll get it!” Antoine confidently responds, “She won’t dare tell Dad.”

Of course when heading home the squealer in his class is hiding behind a tree watching the two friends while Antoine tells Rene he needs a note for an excuse tomorrow on why he wasn’t in class. Rene gives him an old excused note from his mother for him to copy. That night Antoine tries forging the note with his own handwriting. “You sir, please excuse my son Rene who was sick… My son Rene!” He realizes he accidentally uses his friend’s name and wrecked the note, so he burns it in the fireplace. That evening his father comes home and tells Antoine that mother will be home late because her boss needs her for a year-end inventory. Antoine and his stepfather start cooking dinner for the two of them and his stepfather tells Antoine to go more easy on his mother because she is very stressed with work and home.

That evening his stepfather accuses Antoine of stealing his Michelin guide. When Antoine truthfully tells him he didn’t steal it his father thinks he’s lying. The camera focuses on Antoine’s face as you see him hurt that he is accused of something he didn’t do, and you realize why he does steal because he’ll get accused of it anyways even if he doesn’t. That night Antoine can hear his mother coming home late while lying in bed and listens to her and his stepfather arguing.

“My boss drove me home.”

“Your boss!”

“I couldn’t very well refuse, could I?”

“I hope you get overtime for that!”

“I will at the end of the month.”

“Those services are usually paid in cash! By the way, where’s my Michelin guide?”

“How should I know? Ask the boy.”

“He said he didn’t touch it.”

“He lies through his teeth.”

“Like someone else I know.”

“If you raised him better! We’ll send him to the Jesuits or the army orphans. At least I’d have some peace and quite!!”

That next morning the student who squeals rings their doorbell and informs Antoine’s father Antoine wasn’t in school the other day. Antoine’s mother says, “Nothing that boy does surprises me.” Before walking onto school grounds, Antoine tries to figure out an excuse on what to tell his teacher on why he wasn’t in class. When Antoine arrives his teacher really lets him have it for not showing up for school. “A little extra homework and you get sick, huh? Let me see your note.” Antoine doesn’t know what to say so he impulsively says, “It was…my mother… She’s dead!” His teacher apologizes and says he’s sorry.

During the school day his teacher goes easier on Antoine during class, by not calling on him for tough questions. Everything is smooth until Antoine’s parents turn up at his school. They are furious when they are told by his teacher about the lie of his mother dying, and his stepfather slaps him in front of his own classmates. After school Antoine decides not to go home that night because of the fear of being punished and his friend Rene lets him sleep at his uncle’s old printing plant. Antoine leaves a note for his parents and his mother asks his stepfather, “Why kill me off instead of you?” His stepfather tells her, “Personal preference obviously.”

While trying to sleep in the plant Antoine hears some men coming in so he quickly leaves and is wandering the empty streets in the early morning, snatching a bottle of milk because of thirst. He attends school that day and there is a funny scene where his teacher asks him how hard he got it from his parents last night. Antoine calmly says, “Not at all. Everything was fine.” and walks away. His teacher then states to another teacher, “Parents spoil these kids rotten.” When his parents come to the school to find Antoine safe and sound, his mother is relieved.

That night at home for the first time in years his mother treats him affectionately and rubs him down after a bath and tucks him into bed. After she tucks him in his mother tries her best to connect with him by telling him, “I was your age once too, you know. I was stubborn and didn’t want to confide in my parents.”

One of the funniest moments in the film is where Antoine’s physical education teacher is leading the boys in a straight line on a jog through Paris. Truffaut uses a long overshot showing one after another, students from the back of the line dash off two at a time, until the teacher who is at the head of the line only has a few children left. That day in class Antoine is given a paper to write and he decides to write about his grandfather’s death by using the help of a famous writer and poet named Balzac who he truly admirers. Antoine has a shrine dedicated to Balzac and lights a candle for him.

During dinner Antoine accidentally sets the little cardboard shrine on fire and tries to put it out. His parents then help put out the flames, and his stepfather is furious. His mother who is trying to be kinder to her son calms her husband down and says, “Know what we’ll do to lighten things up? We’ll all go the movies!” The three of them all go out to the movies, and after the movie they all stop and get ice cream. On the drive back home they are all laughing, being silly, discussing the movie and for the first time you see this family actually happy together. This scene to me is the best scene in the film.

It seems that Antoine can never catch a break though, even when he tries to do something right. The next day in class his teacher calls him out right in front of his classmates saying, “Doinel, if your paper is first today, it’s because I’ve decided to give the results beginning with the worst. Your search for perfection led you straight to an F, my friend.” The paper he wrote on his grandfather was inspired by the style of Balzac and yet when he pours his heart into writing this essay using some of his favorite quotes from this man, his teacher considers it plagiarism. His teacher cruelly says to everyone, “That Dionel chose to write about his grandfather’s death was his right. We know he doesn’t hesitate to sacrifice his relatives, if necessary.” Antoine tries to defend himself but it’s no use, and he is sent to the principle’s office for “being a miserable plagiarist.”

His best friend Rene sticks up for him and he gets sent to the principle as well. Antoine knows he can’t go home now, because when his stepfather finds out about him going to the principles office he was told he would be sent to a military school. Rene tells him there’s a future in the military but Antoine says he would rather be in the navy because he never seen the ocean, which is a foreshadowing of the ending of the film. Antoine decides to run away again and Rene tells him he can stay at his parents and hide out there. He hides him out in a room his parents never enter and tells Antoine, “my mother drinks, and my father spends all day at the races.”

Rene then steals some of his parents money and the both of them go to the movies while afterwards Rene steals a lobby photo of a star. That night while Rene’s parents are gone they spend time drinking their wine and smoking cigars while playing a board game. When Rene’s father suddenly returns home Antoine hides behind the bed, and the next day the both of them our shooting spit balls out the window at cars.

Eventually things get even worse for Antoine and there’s a powerful moment in the film where you notice things are changing within Antoine’s character. There’s a puppet show and Truffaut focuses on several extended shots of adolescent children gleefully laughing and giggling at the show. While this is going on Antoine and his Rene are sitting in the back talking about finding a way to get more money. This is the pivotal moment of the film where Antoine is no longer the young mischievous prankster but a child who is now lost and interested in getting involved in the seedy side of the adult world.

Him and Rene decide to break into a business building and steal a typewriter to pawn it off and get the cash. Of course when the guy they give it to so he can pawn it tries to take off with it, they catch him in the act and ask for it back. Since they don’t have a way to pawn it (They’re not of age) the two of them don’t know what to do with the typewriter. Antoine foolishly decides to take it back to the original building that he stole it from wearing a hat so the night-watchman doesn’t catch him. While he sneaks in once again to return it is when he is caught. The man who catches him says, “Put that down! Boy is your daddy gonna love this!”

When his stepfather comes he is furious and tells Rene, “take a good look at your pal, cause you won’t be seeing him again for a while.” His stepfather then takes him to the police saying he and his wife tried everything to kindness, persuasion, and punishment, but nothing is working. Antoine is then charged with vagrancy and theft. His stepfather doesn’t want to take him home because he will just run away again so he decides to lock him up with hardened criminals. While Antoine is sharing a cell with prostitutes and thieves, he later gets his mug shots taken. Then there is the powerful shot of his face peering out through the cell bars looking like a young tragic Dickensian character.

During an interview with the judge, Antoine’s mother confesses that Antoine’s father is not his biological father and says, “He married me when the boy was small.” Antoine is then sent to a juvenile detention home for troubled youths. After being at the Juvenile Detention Center for some time, Antoine meets other kids who have committed much worse crimes than him. On visiting day Antoine sees that Rene comes by to try to see Antoine but unfortunately is not allowed in.

In one of the most heartbreaking scenes of the film his mother stops in to visit him. While she is going on about how the neighbors are gossiping about her and his stepfather’s parenting skills because of Antoine being locked up, Antoine notices that she’s wearing a new expensive hat that she must have purchased probably because of the extra money she now has of not having Antoine living with them anymore. He now knows in his heart that his parents won’t take him back. His mother coldly says to him before leaving, “All you’re good for now is reform school or a labor center. You wanted to earn your living? Now we’ll see how you like it.” There is a memorable scene where Antoine sees a psychiatrist at the Detention Center who asks questions about Antoine’s thoughts and unhappiness, which is revealed in a series of monologues.

“Why did you return the typewriter?”

“Well, since I couldn’t sell it or anything, I got scared. I don’t know why I returned it. Just ’cause.”

“Your parents say your always lying.”

“Oh, I lie now and then, I suppose. Sometimes I’d tell them the truth and they still wouldn’t believe me, so I prefer to lie.”

“Why don’t you like your mother?”

“I could always tell my mother didn’t like me. She was always yelling at me for no reason. There were fights at home, and I overheard that my mother had me before she was married. That’s when I found out that she wanted to have an abortion. It’s thanks to my grandmother that I was born.”

“Have you ever slept with a girl?”

“No, but some friends of mine have. They told me where the hookers hang out. So I went and tried to pick up some girls, but they all yelled at me so I got scared and I left.”

In the climax of the film at the Juvenile Detention Center during a game of soccer, Antoine escapes by crawling under the fence. In a beautiful long take of Antoine running away from the Detention Center he eventually makes his way to the ocean (which was what he always dreamed of wanting to see), and yet he realizes it’s a dead-end and there is no place to go as he turns at the camera and the camera freeze-frames.

FRENCH NEW WAVE

The New Wave was a blanket term coined by critics for a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Although never a formally organized movement, the New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of the literary period pieces being made in France and written by novelists, their spirit of youthful iconoclasm, the desire to shoot more current social issues on location, and their intention of experimenting with the film form. “New Wave” is an example of European art cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm.

Using light-weight portable equipment, hand-held cameras and requiring little or no set up time, the New Wave way of film-making presented a documentary style. The films exhibited direct sounds on film stock that required less light. Filming techniques included fragmented, freeze-frames, discontinuous editing, and long takes. The combination of objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary created a narrative ambiguity in the sense that questions that arise in a film are not answered in the end.

Alexandre Astruc’s manifesto, “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera-Stylo”, published in L`Ecran, on 30 March 1948 outlined some of the ideas that were later expanded upon by François Truffaut and the Cahiers du cinéma. It argues that “cinema was in the process of becoming a new mean of expression on the same level as painting and the novel: a form in which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel. This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the ‘camera-stylo.”

Some of the most prominent pioneers among the group, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, began as critics for the famous film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Cahiers co-founder and theorist André Bazin was a prominent source of influence for the movement. By means of criticism and editorialization, they laid the groundwork for a set of concepts, revolutionary at the time, which the American film critic Andrew Sarris called the ‘auteur theory.’

Cahiers du cinéma writers critiqued the classic “Tradition of Quality” style of French Cinema. Bazin and Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, were the dual godfather figures of the movement. These men of cinema valued the expression of the director’s personal vision in both the film’s style and script.

The ‘auteur theory’ holds that the director is the “author” of his movies, with a personal signature visible from film to film. They praised movies by Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, and made then-radical cases for the artistic distinction and greatness of Hollywood studio directors such as Orson Welles, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray. The beginning of the New Wave was to some extent an exercise by the Cahiers writers in applying this philosophy to the world by directing movies themselves.

Truffaut, with The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard, with Breathless (1960) had unexpected international successes, both critical and financial, that turned the world’s attention to the activities of the New Wave and enabled the movement to flourish. Part of their technique was to portray characters not readily labeled as protagonists in the classic sense of audience identification.

The auteurs of this era owe their popularity to the support they received with their youthful audience. Most of these directors were born in the 1930s and grew up in Paris, relating to how their viewers might be experiencing life. They were considered the first film generation to have a “film education”, knowledge of and references to film history. With high concentration in fashion, urban professional life, and all-night parties, the life of France’s youth was being exquisitely captured.

The French New Wave was popular roughly between 1958 and 1964, although New Wave work existed as late as 1973. The socio-economic forces at play shortly after World War II strongly influenced the movement. Politically and financially drained, France tended to fall back on the old popular pre-war traditions. One such tradition was straight narrative cinema, specifically classical French film.

The movement has its roots in rebellion against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), criticizing in particular the way these forms could force the audience to submit to a dictatorial plot-line. They were especially against the French “cinema of quality”, the type of high-minded, literary period films held in esteem at French film festivals, often regarded as ‘untouchable’ by criticism.

New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what was, to them, a much more comfortable and contemporary form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized. French New Wave were also influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema.

The French New Wave featured unprecedented methods of expression, such as long tracking shots (like the famous traffic jam sequence in Godard’s 1967 film Week End). Also, these movies featured existential themes, such as stressing the individual and the acceptance of the absurdity of human existence. Filled with irony and sarcasm, the films also tend to reference other films.

Many of the French New Wave films were produced on tight budgets; often shot in a friend’s apartment or yard, using the director’s friends as the cast and crew. Directors were also forced to improvise with equipment (for example, using a shopping cart for tracking shots). The cost of film was also a major concern; thus, efforts to save film turned into stylistic innovations. For example, in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, after being told the film was too long and he must cut it down to one hour and a half he decided (on the suggestion of Jean-Pierre Melville) to remove several scenes from the feature using jump cuts, as they were filmed in one long take. Parts that did not work were simply cut from the middle of the take, a practical decision and also a purposeful stylistic one.

The cinematic stylings of French New Wave brought a fresh look to cinema with improvised dialogue, rapid changes of scene, and shots that go beyond the common 180° axis. The camera was used not to mesmerize the audience with elaborate narrative and illusory images, but to play with the expectations of cinema. The techniques used to shock and awe the audience out of submission and were so bold and direct that Jean-Luc Godard has been accused of having contempt for his audience. His stylistic approach can be seen as a desperate struggle against the mainstream cinema of the time, or a degrading attack on the viewer’s supposed naivety. Either way, the challenging awareness represented by this movement remains in cinema today. Effects that now seem either trite or commonplace, such as a character stepping out of their role in order to address the audience directly, were radically innovative at the time.

Classic French cinema adhered to the principles of strong narrative, creating what Godard described as an oppressive and deterministic aesthetic of plot. In contrast, New Wave filmmakers made no attempts to suspend the viewer’s disbelief; in fact, they took steps to constantly remind the viewer that a film is just a sequence of moving images, no matter how clever the use of light and shadow. The result is a set of oddly disjointed scenes without attempt at unity; or an actor whose character changes from one scene to the next; or sets in which onlookers accidentally make their way onto camera along with extras, who in fact were hired to do just the same.

At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods, and were inspired by the generation of Italian Neorealists before them. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to the theatre.

Finally, the French New Wave, as the European modern Cinema, is focused on the technique as style itself. A French New Wave film-maker is first of all an author who shows in its film his own eye on the world. On the other hand the film as the object of knowledge challenges the usual transitivity on which all the other cinema was based, “undoing its cornerstones: space and time continuity, narrative and grammatical logics, the self-evidence of the represented worlds.” In this way the film-maker passes “the essay attitude, thinking – in a novelist way – on his own way to do essays.”

The Left Bank, or Rive Gauche, group is a contingent of filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, first identified as such by Richard Roud. The corresponding “right bank” group is constituted of the more famous and financially successful New Wave directors associated with Cahiers du cinéma. Unlike the Cahiers these directors were older and less movie-crazed. They tended to see cinema akin to other arts, such as literature. However they were similar to the New Wave directors in that they practiced cinematic modernism. Their emergence also came in the 1950s and they also benefited from the youthful audience. The two groups, however, were not in opposition; Cahiers du cinéma advocated Left Bank cinema.

Left Bank directors include Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. Roud described a distinctive “fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking”, as well as an identification with the political left. The filmmakers tended to collaborate with one another, Jean-Pierre Melville, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Marguerite Duras are also associated with the group. The nouveau roman movement in literature was also a strong element of the Left Bank style, with authors contributing to many of the films. Left Bank films include La Pointe Courte, Hiroshima mon amour, La jetée, Last Year at Marienbad, and Trans-Europ-Express.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

François Truffaut’s first feature, The 400 Blows (Les Quatre cents coups), was more than a semi-autobiographical film; it was also an elaboration of what the French New Wave directors would embrace as the caméra–stylo (camera-as-pen) whose écriture (writing style) could express the filmmaker as personally as a novelist’s pen. It is one of the supreme examples of “cinema in the first person singular.” In telling the story of the young outcast Antoine Doinel, Truffaut was moving both backward and forward in time—recalling his own experience while forging a filmic language that would grow more sophisticated throughout the ‘60s.

The 400 Blows (whose French title comes from the idiom, faire les quatre cents coups—“to raise hell”) is rooted in Truffaut’s childhood. Born in Paris in 1932, he spent his first years with a wet nurse and then his grandmother, as his parents had little to do with him. When his grandmother died, he returned home at the age of eight. An only child whose mother insisted that he make himself silent and invisible, he took refuge in reading and later in the cinema.

Like Antoine, Truffaut found a substitute home in the movie theater: He would either sneak in through the exit doors and lavatory windows, or steal money to pay for a seat. In The 400 Blows, Antoine and René reenact the delinquency and cinemania of the young Truffaut and Robert Lachenay (who was an assistant on The 400 Blows). Their touching friendship is captured in René’s unsuccessful attempt to visit Antoine at reform school.

And like Antoine, Truffaut ran away from home at the age of eleven, after inventing an outrageous excuse for his hooky-playing. Instead of Antoine’s lie about his mother’s death, Truffaut told the teacher that his father had been arrested by the Germans. The recent revelation that Truffaut’s biological father—whom he never knew—was a Jewish dentist renders this excuse especially poignant. His mother was only seventeen when Truffaut was born; at eighteen, she met Roland Truffaut, whom she married in 1933, and he recognized the boy as his own. Antoine’s uneasy relationship to his adoptive father reflects that of the director. After young François himself committed minor robberies, the senior Truffaut turned him over to the police.

It is not surprising that one of the dominant, although subtle, motifs throughout Truffaut’s work is paternity (nor that his entire career is marked by filial devotion to mentors like Renoir and Hitchcock). In The 400 Blows, the class in English pronunciation revolves around a question that can be articulated only with difficulty: “Where is the father?”—a phrase that resonates both within the film (Antoine has never known his real father) and in the director’s life.

Antoine Doinel became a composite of two compelling individuals, Truffaut and the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. Out of sixty boys who responded to an ad, the director chose the 14-year-old Léaud because “he deeply wanted that role . . . an anti-social loner on the brink of rebellion.” He encouraged the boy to use his own words rather than sticking to the script. The result fulfilled Truffaut’s avowed aim, “not to depict adolescence from the usual viewpoint of sentimental nostalgia, but . . . to show it as the painful experience that it is.”

Anticipating Truffaut’s later preoccupation with the emotional nuances of libidinal love, The 400 Blows is also a tale of sexual awakening: We see Antoine at his mother’s vanity table, toying with her perfume and eyelash curler; later he is fascinated by her legs as she removes her stockings. The stormy relationship of Antoine’s parents—a constant drama of infidelity, resentment, and reconciliation—foreshadows the romantic and marital tribulations of Antoine himself throughout the Doinel cycle, and offers compelling clues to decode the male protagonists of Truffaut’s films in general.

The last shot has been justly celebrated for its ambiguity. This brief but haunting release from the harrowing experiences that fill the movie brings Truffaut’s surrogate self in direct contact with his audience—an intimacy he was to pursue throughout his career. Truffaut’s zoom in to freeze-frame (more arresting in 1959, before this technique became a stock-in-trade of television commercials) provides a mirror image of an earlier shot in the police station. When Antoine is arrested for stealing a typewriter, he is fingerprinted and photographed for the files. The mug shot is in fact a freeze-frame that conveys the definitive and permanent way in which he has been caught.

That The 400 Blows is a record—even an exorcism—of personal experience is first alluded to in Antoine’s scribbling of self-justifying doggerel on the wall while being punished. On a larger scale, we can see the film as Truffaut’s poetic mark on the wall, or his attempt to even the score; by the last scene, the sea washes away Antoine’s footprints as the film “cleans the slate”—although that final image remains indelible.

-Annett Insdorf

Francois Truffaut is known to have made some of the most important and influential films ever made. Shoot the Piano Player was a sort of homage to the American gangster films, about a piano player who has a secret criminal past. And then he directed Jules and Jim which is a masterpiece and one of my personal favorite films of all time. It tells a tragic romance between two best friends who have been in love with the same woman over the years and the effect both positive and negative that she has on both their lives. Truffaut made a love letter about the inner workings of the movie industry titled, Day for Night which not only stars an older Jean-Pierre Leaud, but it ironically stars Truffaut as the film director. (There is a flashback memory to the director, as a boy, snatching a still of Citizen Kane from in front of a theater which brings back the sequence in The 400 Blows.) The Last Metro tells a story about an actress married to a Jewish theater owner who she must keep hidden from the Nazis while doing both of their jobs.

And yet The 400 Blows will always be the film that would define Truffaut. Filmmakers Akira Kurosawa, Luis Buñuel, Satyajit Ray, Jean Cocteau and Carl Dreyer have cited The 400 Blows as one of their favorite movies. Akira Kurosawa called it “one of the most beautiful films that I have ever seen,” and it is Ranked #29 in Empire magazines “The Best Films Of World Cinema” in 2010. Truffaut died way too young, from an unfortunate brain tumor at the age 52, but even with his life drastically shortened he accomplished so much. Truffaut was always known as a very compassionate man, who had such a passion and love for the movies. While directing Truffaut found time to write about other films and legendary film directors, most famously Alfred Hitchcock which who was always a personal favorite of his. Truffaut wrote a classic book-length, film-by-film interview with the man and over the years the two actually became very good friends. Starting out as a critic Truffaut decided to want to make films of his own after seeing Orson Welles noir classic Touch of Evil at the Expo 58 which then inspired him to make his feature film début in 1959 with The 400 Blows. Truffaut once stated: “I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between.”

The 400 Blows is personally one of my all time favorite films probably because I can personally relate to the tribulations of the character of Antoine Doinel. He’s not necessarily a bad kid, it just seems like the authority figures in his life look at him in the worst possible light, and didn’t seem to want to encourage him or guide him in any way. And because of no real structure and guidance at home or at school, he slowly gets off track at makes poor decisions which lead him into crime. In the film he’s not even so much a troublemaker as he is on being unlucky, and it seems that Antoine’s teacher seems to have him targeted and singled out him out as the bad student in the class. Antoine really is no different from his other classmates, he’s just unfortunately always the one who gets caught and punished. His mother and step-father never acknowledge his presence and when they do it’s usually of things he needs to be doing, like taking out the trash or things he is doing wrong, like his bad grades in school. They never seem to notice the good qualities that Antoine has, most especially his passion for writing and for the great poet Balzac.

And yet like the complexity of life, no one character in Antoine’s life is truly unlikable or necessarily to blame for Antoine ending predicament. They’re much more unstable households and unqualified parents that children have to unfortunately go home to, parents that either have the addiction of alcohol, drugs or who are physically and sexually abusive. Antoine’s parents don’t necessarily have a very strong bond with Antoine and their communication between one another is very distant and cold. Besides Antoine’s parents struggling with their marital issues, and of his mother’s current infidelities with other men in the city, his parents overall seem to care about the welfare of their son. No marriage or family household is picture perfect and Antoine seems to come from a household where his parents at least lay down strict firm restrictions, and rules, and who seem to truly care about the whereabouts of their son. Take for instance the sequence where Antoine hides out as his best friend Rene’s house for several days. Rene’s parents are heavy gamblers and drinkers who seem to not be involved at all in their son’s daily life. The antics that Rene pulls on his parents, like skipping school for several days in a row or sneaking Antoine in the home as the two spent their day drinking liquor and smoking cigars, are things Antoine could never get away with at his home; Which is why Antoine is hiding over there in the first place. A lot of people could point out Antoine’s mother as being an unlikable character because of her infidelities and how mean and cruel she seems to treat Antoine. And yet there are those few tender moments where she tries to be her best to be compassionate and understanding to her son; and even on one instance comes up with the idea for the family to go out and see a movie, after Antoine accidentally set the shrine of the poet he admires on fire. In one scene Antoine’s mother is relieved her son has come home safe, she washes him and sweetly tucks him in bed. Then she tries her best to communicate with him by discussing her own rebellious childhood and how she didn’t listen to well with her parents. It’s a truly heartbreaking scene as you can obviously see their isn’t genuinely any loving connection between Antoine and his mother. His mother is the type of woman who just lacks the ability to express genuine and loving feelings to not only her son but to her husband as well. Some people aren’t truly loving and compassionate people but that doesn’t stop them from trying to be, and when we see his mother really put forth an effort to connect with her son; it’s just too late. I’ve always wondered if I didn’t have the escapism of cinema or wasn’t raised in a healthy loving family, if I eventually would have taken a darker path that could have led to crime or even jail. The antics Antoine commits in the beginning of the film are simple youth pranks that I myself committed in my classrooms when I was younger, and I am guilty of skipping school and saying white lies to my parents and teachers in the past. The shrine that Antoine has for his mentor and role model Balzac, is similar to my books on Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini; people who I admire and am passionate about, and are things the adults in my life would never understand. The only real difference between Antoine and myself is that I’ve always had loving supporting parents that I could go to when in need, and because of this I knew where to draw the line with my misbehavior; because I didn’t want to hurt them. The 400 Blows is a masterpiece and is on my top 10 films of all time. The tragic character of Antoine will always hold a special place in my heart because of how much I can relate to the character. The films final ambiguous shot is heartbreaking because the film ends on a note that is like life; which is uncertainty. The film’s famous final shot, is a zoom in to a freeze frame, showing Antoine looking directly into the camera, at us. He has just run away, and is on the beach, caught between land and water, and it is the first time he has ever seen the sea. I have always wondered what Antoine was thinking at that very moment when looking into the camera, knowing now that he’s at a crossroad in his life, not knowing where it will take him, and we as an audience don’t know where he will go.

And yet like the complexity of life, no one character in Antoine’s life is truly unlikable or necessarily to blame for Antoine ending predicament. They’re much more unstable households and unqualified parents that children have to unfortunately go home to, parents that either have the addiction of alcohol, drugs or who are physically and sexually abusive. Antoine’s parents don’t necessarily have a very strong bond with Antoine and their communication between one another is very distant and cold. Besides Antoine’s parents struggling with their marital issues, and of his mother’s current infidelities with other men in the city, his parents overall seem to care about the welfare of their son. No marriage or family household is picture perfect and Antoine seems to come from a household where his parents at least lay down strict firm restrictions, and rules, and who seem to truly care about the whereabouts of their son. Take for instance the sequence where Antoine hides out as his best friend Rene’s house for several days. Rene’s parents are heavy gamblers and drinkers who seem to not be involved at all in their son’s daily life. The antics that Rene pulls on his parents, like skipping school for several days in a row or sneaking Antoine in the home as the two spent their day drinking liquor and smoking cigars, are things Antoine could never get away with at his home; Which is why Antoine is hiding over there in the first place. A lot of people could point out Antoine’s mother as being an unlikable character because of her infidelities and how mean and cruel she seems to treat Antoine. And yet there are those few tender moments where she tries to be her best to be compassionate and understanding to her son; and even on one instance comes up with the idea for the family to go out and see a movie, after Antoine accidentally set the shrine of the poet he admires on fire. In one scene Antoine’s mother is relieved her son has come home safe, she washes him and sweetly tucks him in bed. Then she tries her best to communicate with him by discussing her own rebellious childhood and how she didn’t listen to well with her parents. It’s a truly heartbreaking scene as you can obviously see their isn’t genuinely any loving connection between Antoine and his mother. His mother is the type of woman who just lacks the ability to express genuine and loving feelings to not only her son but to her husband as well. Some people aren’t truly loving and compassionate people but that doesn’t stop them from trying to be, and when we see his mother really put forth an effort to connect with her son; it’s just too late. I’ve always wondered if I didn’t have the escapism of cinema or wasn’t raised in a healthy loving family, if I eventually would have taken a darker path that could have led to crime or even jail. The antics Antoine commits in the beginning of the film are simple youth pranks that I myself committed in my classrooms when I was younger, and I am guilty of skipping school and saying white lies to my parents and teachers in the past. The shrine that Antoine has for his mentor and role model Balzac, is similar to my books on Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini; people who I admire and am passionate about, and are things the adults in my life would never understand. The only real difference between Antoine and myself is that I’ve always had loving supporting parents that I could go to when in need, and because of this I knew where to draw the line with my misbehavior; because I didn’t want to hurt them. The 400 Blows is a masterpiece and is on my top 10 films of all time. The tragic character of Antoine will always hold a special place in my heart because of how much I can relate to the character. The films final ambiguous shot is heartbreaking because the film ends on a note that is like life; which is uncertainty. The film’s famous final shot, is a zoom in to a freeze frame, showing Antoine looking directly into the camera, at us. He has just run away, and is on the beach, caught between land and water, and it is the first time he has ever seen the sea. I have always wondered what Antoine was thinking at that very moment when looking into the camera, knowing now that he’s at a crossroad in his life, not knowing where it will take him, and we as an audience don’t know where he will go.