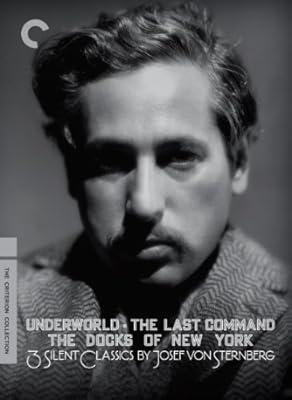

Three Silent Classics by Josef Von Sternberg (Underworld / Last Command / Docks of New York) (The Criterion Collection)

Manufacturer Description

Note on Boxed Sets: During shipping, discs in boxed sets occasionally become dislodged without damage. Please examine and play these discs. If you are not completely satisfied, we'll refund or replace your purchase.

We toss the term great director around casually, but a handful of people truly merit the title and Josef von Sternberg is among them. His films are at once exotic, extravagant, and rigorously controlled. Sternberg was the visual stylist supreme, his compositions filled with such extraordinary texture and lighting that space comes alive, takes on depth and electricity. And the characters and performances that inhabit those spaces, the emotional and ethical dramas they grapple with, are sometimes shocking in their modernity even as they clearly come to us from another era. Individually and as a collective body of work, Sternberg's films are mesmerizing. Yet of our greatest directors, he's the one whose work probably is least well known today, and has been least well served on video and DVD. So all hail Criterion for releasing three exemplary Sternberg pictures, handsomely restored. The fact that they're silent productions makes them all the rarer, with opportunities to see them in later years mostly limited to festival and museum showings.

Underworld (1927), Sternberg's first great popular success, is often credited with initiating the craze for gangster pictures. There's some truth in that; the genre had been around for years, but Underworld elevated it in class and laid crucial groundwork for such early-talkie milestones as Little Caesar and, most strikingly, Scarface. Ex-Chicago crime reporter Ben Hecht, who won the first Academy Award given for original story, chipped in a lot of street-smart color but snickered at what Sternberg did with it. That's understandable. Sternberg really isn't interested in gangsters. He just appreciates the opportunity presented by a gangland ball he can strew with grotesque revelers, and so choke with streamers and confetti that crossing the room becomes a slog. Or the dramatic and poetic possibilities of muting and intensifying violence in the same stroke, by having a hoodlum draw and then doubly conceal his revolver behind a cloud of cigarette smoke and a kerchief. Or not showing a gun at all, but having the force and smoke from its blast set a curtain to flapping. But the most Sternbergian image in the film is the moment a gangster's moll named Feathers appears at the top of the stairs leading to a cellar saloon, and a single filament of her signature costume drifts down through the air. This is observed by a camera movement all its own, by two men who will become rivals for Feathers's heart, by the crowd gathered in the saloon, and by a movie audience awestruck at such visual audacity and delicacy. The romantic triangle of Feathers (Evelyn Brent), her mobster lover "Bull" Weed (George Bancroft), and "Rolls-Royce" (Clive Brook), the lawyer-turned-drunken bum Bull sentimentally rescues, is the real focus of the kind of action Sternberg cares about. The evolution of their characters and their relationships is conveyed with a subtlety light-years away from conventional silent-movie acting. This film was such a hit that the New York exhibitor went to a round-the-clock schedule to accommodate the crowds, and its three leading players all became major stars.

Instead of an urban battleground for mobsters, The Last Command (1928) takes place in two exotic realms: Russia on the brink of the 1917 revolution and 1928 Hollywood. In the latter, a movie director (William Powell) is preparing to shoot an epic set in the former. Linking the two eras is a down-on-his-luck Hollywood extra (Emil Jannings) assigned to play a Russian general--which, unbeknownst to anyone else, he once was. After establishing this framework the movie shifts into the Russian past, where the general--who's also a grand duke--must interrupt his waging of an increasingly pointless Great War to deal with a captured pair of revolutionaries. One is an actress (Evelyn Brent), with whom the general falls in love. The other is, hmmm, the man (William Powell) who 11 years later will be that Hollywood director. Sternberg mounts a fine frenzy in the pre-revolutionary Russian scenes and sets up ironic contrasts between the film's two worlds--say, a martial parade with the general at the height of his power, visually echoed in the cattle-call procession of Hollywood extras hoping for a day's work. Emil Jannings won the first Academy Award for best actor, and he would top this work the following year in Sternberg's German-made The Blue Angel; but it's Powell and the wonderfully low-key performance of Brent that signal where Sternberg's direction of actors was headed.

Sternberg's other 1928 film, The Docks of New York, stands with Murnau's Sunrise and Borzage's Street Angel as the peak of visual artistry and expressiveness in late-silent-era Hollywood. Story, narrative, linear cause-and-effect logic is never a major factor in Sternbergian filmmaking, and Docks affords the most definitive, and triumphant, demonstration of this. It all transpires in a day, most of which feels like night and in any event is contained within a seedy waterfront bar. George Bancroft (the mobster-hero of Underworld) plays a ship's stoker who, during a rare release from the smoky underworld in which he works and lives, becomes involved with two women--a would-be suicide (Betty Compson) and a hardened B-girl (Olga Baclanova). The abortive act of suicide is visually portrayed in shimmering reflection on the harbor's surface, and a later act of murder will involve an uncanny, nearly vertical shot in which the earth under people's feet seems to be water. This is a film you don't remember so much as find yourself haunted by.

DVD extras add useful historical and interpretive context for appreciating the three movies. UCLA film professor Janet Bergstrom and indefatigable connoisseur of directorial artistry Tag Gallagher supply pointed visual essays--Bergstrom being especially good on tracing Sternberg's origins, Gallagher zeroing in on Sternberg's stylistic selections and his "transformative direction of Evelyn Brent" just a year or so before his epic seven-film collaboration with Marlene Dietrich set in. Sternberg himself is heard from in a 40-minute documentary-interview done for Swedish television in 1968, a year before the director died; his voice and delivery are most distinctive. Somewhere in the course of these extras a Sternberg credo is quoted: "Art is the compression of infinite spiritual power into a confined space." Yes, that says it. And he did it. --Richard T. Jameson

Key Product Details

- Director: Josef Von Sternberg

- Number Of Discs: 3

- Run Time: 244 (Minutes)

- UPC: 715515059510

![The Blue Angel: Kino Classics 2-Disc Ultimate Edition [Blu-ray] The Blue Angel: Kino Classics 2-Disc Ultimate Edition [Blu-ray]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/511BcK4pPSL.01_SL120_.jpg)