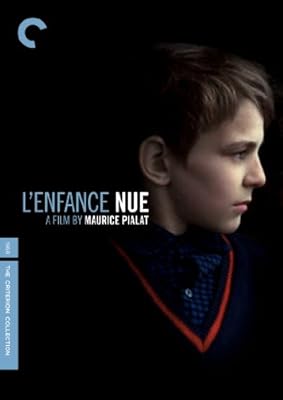

L'enfance Nue (The Criterion Collection)

Price:

$22.46

As of 2025-04-04 08:52:37 UTC (more info)

Product prices and availability are accurate as of 2025-04-04 08:52:37 UTC and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on http://www.amazon.com/ at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.

Availability:

Not Available - stock arriving soon

Product Information (more info)

CERTAIN CONTENT THAT APPEARS ON THIS SITE COMES FROM AMAZON SERVICES LLC. THIS CONTENT IS PROVIDED 'AS IS' AND IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE OR REMOVAL AT ANY TIME.

Manufacturer Description

The singular French director Maurice Pialat (Loulou, À nos amours) puts his distinct stamp on the lost-youth film with this devastating portrait of a damaged foster child. We see François (Michel Terrazon), on the cusp of his teens, shuttled from one home to another, his behavior growing increasingly erratic, and his bonds with his surrogate parents perennially fraught. In this, his feature debut, Pialat treats this potentially sentimental scenario with astonishing sobriety and stark realism. With its full-throttle mixture of emotionality and clear-eyed skepticism, L’ENFANCE NUE (Naked Childhood) was advance notice of one of the most masterful careers in French cinema, and remains one of Pialat’s finest works.

Like a dark reflection of The 400 Blows, L'Enfance Nue (or Naked Childhood), Maurice Pialat's first feature film, follows the struggles of François (Michel Terrazon), a boy in the foster-care system who lashes out against even those who show him kindness. There's no plot to speak of--François is kicked out of one foster home and ends up with an elderly couple who try to cope with his erratic nature--but every scene is so rich with human conflict that the movie is riveting. The film is almost aggressively plain--the elegance and musical flow of Truffaut's childhood movie is utterly absent. Pialat (A Nous Amours, Loulou) wants to be utterly transparent, to create immediate contact with François's bittersweet existence, and the result is vivid and affecting. As ever with a Criterion release, the extras are superb: an interview with Pialat on French television, in which he discusses frankly and clinically the movie's commercial failure; a documentary that's half "making of," half investigation of France's foster-care system (featuring some heartbreaking interviews with foster children, including the boy that François was based on); interviews with Pialat's cowriter and assistant director; and a thoughtful critical essay. But the crown jewel is a short film by Pialat from 1960, L'Amour Existe, a stunningly beautiful and genre-defying meditation on postwar suburban life in Paris, seething with what can only be described as a scathing melancholy. --Bret Fetzer

Like a dark reflection of The 400 Blows, L'Enfance Nue (or Naked Childhood), Maurice Pialat's first feature film, follows the struggles of François (Michel Terrazon), a boy in the foster-care system who lashes out against even those who show him kindness. There's no plot to speak of--François is kicked out of one foster home and ends up with an elderly couple who try to cope with his erratic nature--but every scene is so rich with human conflict that the movie is riveting. The film is almost aggressively plain--the elegance and musical flow of Truffaut's childhood movie is utterly absent. Pialat (A Nous Amours, Loulou) wants to be utterly transparent, to create immediate contact with François's bittersweet existence, and the result is vivid and affecting. As ever with a Criterion release, the extras are superb: an interview with Pialat on French television, in which he discusses frankly and clinically the movie's commercial failure; a documentary that's half "making of," half investigation of France's foster-care system (featuring some heartbreaking interviews with foster children, including the boy that François was based on); interviews with Pialat's cowriter and assistant director; and a thoughtful critical essay. But the crown jewel is a short film by Pialat from 1960, L'Amour Existe, a stunningly beautiful and genre-defying meditation on postwar suburban life in Paris, seething with what can only be described as a scathing melancholy. --Bret Fetzer

Key Product Details

- Director: Maurice Pialat

- Number Of Discs: 1

- Run Time: 83 (Minutes)

- UPC: 715515061612

![La Chienne [VHS] La Chienne [VHS]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51XY1BMPT9L.01_SL120_.jpg)

![Lonesome (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray] Lonesome (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51xdHXR2KtL.01_SL120_.jpg)