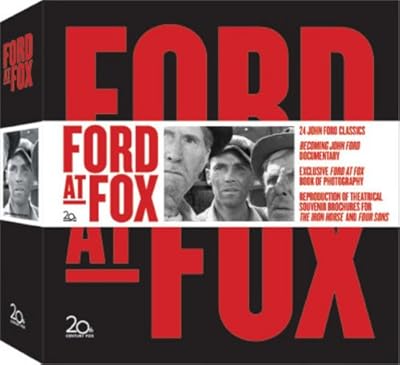

Ford At Fox - The Collection

Manufacturer Description

Disc 1: WHAT PRICE GLORY Disc 2: MY DARLING CLEMENTINE Disc 3: HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY Disc 4: TOBACCO ROAD Disc 5: GRAPES OF WRATH Disc 6: DRUMS ALONG THE MOHAWK Disc 7: WEE WILLIE WINKIE Disc 8: YOUNG MR. LINCOLN Disc 9: PRISONER ON SHARK ISLAND Disc 10: STEAMBOAT AROUND THE BEND Disc 11: WORLD MOVES ON Disc 12: PILGRIMAGE/BORN RECKLESS Disc 13: DOCTOR BULL/JUDGE PRIEST Disc 14: FOUR MEN AND A PRAYER/SEAS BENEATH Disc 15: WHEN WILLIE COMES HOME/UP THE RIVER Disc 16: FOUR SONS Disc 17: THREE BAD MEN/HANGMAN'S HOUSE Disc 18: JUST PALS Disc 19: BECOMING JOHN FORD DOCUMENTARY Disc 20: THE IRON HORSE SPECIAL EDITION UK VERSION DISC 1 Disc 21: THE IRON HORSE US VERSION: DISC 2

For anyone with a passion for vintage American cinema, it's difficult to imagine a more spectacular or more deeply gratifying occasion than the DVD release of Ford at Fox: The Collection. This mega-box is like a film archive unto itself ... or maybe permanent browsing rights over a wing of the Library of Congress. To be sure, there have been plenty directorial boxed sets, including several devoted to John Ford; and Ford made quite a bit of film history--and many of his best movies--away from Fox Films and its post-1935 avatar, 20th Century–Fox. But this treasure trove of 21 discs, encompassing just about half of the 50 titles Ford directed for Fox between 1920 and 1952, is unparalleled.

It isn't just the career highlights, though those have been treated royally. The Iron Horse, the epic 1924 Western that became a breakout success for its 30-year-old director, is presented in two editions, a British release version and the American version. Three Bad Men (1926), Ford's even better, last silent Western, is here, as well as the two pictures that brought him back-to-back best director Oscars in 1940-41, The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley. The Grapes of Wrath has been newly restored, and you'll find three other towering collaborations with Henry Fonda: Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), and My Darling Clementine (1946)--both the director's preview cut and the release version.

Yet the real richness of Ford at Fox isn't limited to the known masterpieces. Some of it has to do with the dozen-and-a-half titles that are far from household words--the movies that put us in touch with the self-described "picture man" who did a "job of work" for the studio where he was under contract for much of the three decades beginning with Just Pals in 1920. Some of these are great films awaiting proper recognition. But even the least among them give off the ozone snap of discovery, affording simultaneous insights into the evolution of an artist, a medium, and a distinctive studio.

In this regard, the new feature-length documentary Becoming John Ford is an invaluable element of the set. Premier Ford biographer Joseph McBride, screenwriter Lem Dobbs, Peter Fonda, and others astutely testify about not only the life, artistry, and cantankerous personality of the director but also Fox studios and the mogul who served as a key Ford collaborator, Darryl F. Zanuck. Ford famously despised producers, but he respected Zanuck's movie sense and was content to leave the cutting of their films to him. (To the nighttime scene in The Grapes of Wrath when Tom Joad wanders outside the fruit-pickers' barracks and finds the strikers' encampment, Zanuck added the sound of crickets--a touch that made the superbly composed and lighted moment more "Fordian" than ever.)

Fox was the studio most identified with Americana, even before Zanuck--the favorite son of Wahoo, Nebraska--took charge. And so the legacy of Ford at Fox includes the three pictures he made with the beloved actor, comedian, and national political scold Will Rogers. Doctor Bull (1933) is a scrappy adaptation of a James Gould Cozzens novel, notable chiefly for its wintry New England atmosphere (Ford was a native Down Easter), but Judge Priest (1934) and Steamboat Round the Bend (1935) are luminous fables from the rural South. Judge Priest is especially remarkable for its subversive playing-off of Rogers' wily-rascal persona against the sly Stepin Fetchit in profoundly egalitarian comic scenes; the movie has been neglected because of Fetchit's infamous political incorrectness, but it has, and deserves, a place of honor here.

Also very fine is the 1936 The Prisoner of Shark Island, about the martyrdom of Dr. Samuel Mudd (Warner Baxter), who unwittingly set the leg John Wilkes Booth broke following his assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The moment of Lincoln's death, the president virtually passing into history before our eyes, is a mystical triumph by Ford and cinematographer Bert Glennon. Critic Joe McBride claims Pilgrimage (1933) as one of Ford's early masterpieces and likens the dark-hearted Hannah Jessop, played by stage actress Henrietta Crosman, to the similarly driven Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (not a Fox picture and not included in this set). The setting is again the rural South, and to break up her son's romance with a local girl, Hannah forces him to march off to war in France--where he is killed. The rest of the film becomes, spiritually and then literally, a redemptive journey for Hannah. This stark character study lacks marquee names but has Ford's heart and some of his most powerfully visualized sequences.

Pilgrimage, like the late silents Four Sons and Hangman's House (both 1928), displays evidence of how influenced Ford was in that period by German director F.W. Murnau, who had come to Fox in 1927 to make Sunrise; Four Sons, a mostly German-set story, was even shot on sets left over from the Murnau picture. The essential Ford style was based on dynamism defined within a fixed frame, but watching the director experiment here with elaborate camera movement is fascinating. Similarly, the gangster movies Up the River and Born Reckless (both 1930) and the WWI naval adventure Seas Beneath (1931) take their interest not from their slapdash scenarios but from Ford's crash course in accommodating the presence of sound. Seas Beneath is especially striking among early talkies for being filmed almost entirely in the open air, on the water and on picturesque Catalina Island, with astonishing long-take, real-time coverage of submarines surfacing and submerging, boats sinking, and a naval artillery duel nerve-wracking in its relentless slowness.

For much of his tenure at Fox, Ford had little to say about what films he'd be assigned, or who'd be cast in them. His response was to fill the backgrounds of his movies with his personal stock company of memorably ugly mugs (supremely, Jack Pennick), and to improvise passages of visual poetry or comedy (a baseball game amid the WWI section of Born Reckless!) to keep from getting bored. Apart from some anthology-worthy battlefield sequences, the 1934 The World Moves On is so diffuse and devoid of interest in its rambling family saga, we suspect it might have been the film that inspired one of the great Ford legends: how, advised by the front office that his current production was falling behind, he tore a handful of pages out of the script and said, "Now we're back on schedule."

Mostly, though, the picture man triumphed in spite of himself. Saddling John Ford with a Shirley Temple movie would seem to border on insult, but the director turned the Kipling-based Wee Willie Winkie (1937) into something enchanting instead of cloying. Also partly set on the Indian frontier, Four Men and a Prayer (1938)--a preposterous Boy's Own Adventure tale that hops from India to England to Latin America to Egypt as the titular quartet of British brothers try to clear their late father's name--was just about Ford's last obligatory assignment before embarking on the amazing 1939–41 streak of The Grapes of Wrath et al.; he disliked the story (and the British), but he turned an Indian saloon scene into a classic "Oirish" brawl, and invested a night of civil war in a Latin American town with a memorably surreal air of shock and terror.

How might Ford at Fox have evolved if WWII hadn't intervened? The director spent the war years shooting documentaries (several are included on the Becoming John Ford disc). Upon mustering out, his ambitions focused on developing personal productions for Argosy Pictures, the company he had formed with Merian C. (King Kong) Cooper before the war. Apart from My Darling Clementine, Ford directed only two more pictures for Fox, When Willie Comes Marching Home (1950) and an inferior remake of the silent Raoul Walsh classic What Price Glory (1952)--both semi-musicals featuring Fox's new star Dan Dailey. So, anticlimactically, Ford at Fox: The Collection ends there. But let's not dwell on that; this big box is very full. "There is no fence round time," the narrator says in How Green Was My Valley, "you can go back and have of it what you will." The films of John Ford are forever. --Richard T. Jameson

Key Product Details

- Number Of Discs: 21

- Run Time: 2399 (Minutes)

- UPC: 024543482864

- Director0: Andrew Bennison

![The Grapes of Wrath [Blu-ray] The Grapes of Wrath [Blu-ray]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51Vfj6aHhXL.01_SL120_.jpg)

![Tobacco Road (1941) ( Tobacco Rd ) [ NON-USA FORMAT, PAL, Reg.2 Import - Spain ] Tobacco Road (1941) ( Tobacco Rd ) [ NON-USA FORMAT, PAL, Reg.2 Import - Spain ]](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51kuiH4cq7L.01_SL120_.jpg)