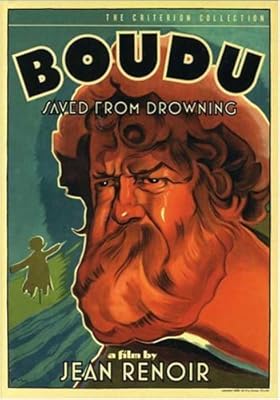

Boudu Saved from Drowning (The Criterion Collection)

Manufacturer Description

Long before there were hippies, there was, sublimely, Boudu. In 1932 director Jean Renoir and French star Michel Simon, fresh from their early-sound triumph La Chienne, decided to re-team in adapting a stage farce about a derelict rescued from the river by a bookseller and groomed for bourgeois society. The bookseller's idea proves to be disastrous, though working through all the possibilities for disruption and catastrophe is a slow-gathering and hilarious process. Simon always seemed as much force of nature as mere actor, and his and Renoir's inspiration is to make Boudu the vagabond not a satyr or opportunist or noble savage or de facto sociopolitical anarchist, but simply an oversized manchild with no more guile or conscious agenda than the shaggy dog whose sudden defection led him to throw himself into the Seine. If his insistence on leaving a downy-soft bed to sleep in the hall happens to block the door to the maid's room, where his benefactor Lestingois is wont to sneak after the wife's asleep, well, Boudu doesn't really plan it that way. And if he leaves a wet lugie between the pages of a first-edition Balzac, well, they asked him not to spit on the floor, after all!

We can see that the original farce (by René Fauchois) was probably pretty funny to begin with, but Renoir makes of it much, much more. Boudu Saved from Drowning--arguably the first French New Wave film, nearly 30 years before there was a New Wave--is one of those cardinal works in which we can see, and experience anew, a great filmmaker inventing the cinema. Without jettisoning the formal qualities of the theatrical farce, Renoir opens his film to light, fresh air, and the teeming multifariousness of Parisian street life; the denizens of the city become unwitting extras in the movie as Boudu first shambles, then prances, among them. The deep-focus camerawork is exhilarating, but even the gregarious roughness of the production feels right, indeed essential. "I believe that perfection is even dangerous," Renoir remarked of his own movie. "If a film is perfect, the public has nothing to add.... The audience should always be trying to finish a picture, ... fill in the holes which we didn't fill." Collaborating on Boudu is a glorious experience. --Richard T. Jameson

Key Product Details

- Director: Jean Renoir

- Number Of Discs: 1

- Run Time: 85 (Minutes)

- UPC: 037429207925