Rocco and His Brothers (1960)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Rocco and his Brothers Visconti” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Rocco and his Brothers is one of the most operatic melodrama’s of all time, involving a modern Italian family and their personal experiences when moving to the city of Milan one cold winter. Italian director Luchino Visconti was an aristocrat, a homosexual, a Marxist, and a director of theater and opera, becoming one of the major influences in the Italian neo realism movement. He had a love and respect for tradition, decadence, and seamy social realism, as the story of Rocco and his Brothers had an obvious undercurrent of flamboyant characterizations and subtle homoerotic that Visconti never quite reconciles. Following the death of her husband, Rosaria Parondi decides to pick up and move to the city of Milan along with four of her sons: Simone, Rocco, Ciro, and Luca; while Vincenzo, the eldest of the brothers has already established himself there. Unfortunately their timing couldn’t be worse, as they arrive on the night of Vincenzo’s engagement party with the beautiful Ginetta (Claudia Cardinale), whose home he has made welcome. The two families take an instant dislike to each other, and the night ends up horribly as the Parondi family stalk out, and Vincenzo’s engagement is temporary broken. The story is divided into chapters focused loosely on each brother, as the movie chronicles the Parondi’s struggle to get by in Milan, while the brothers take odd jobs and the family endures life in a cramped tenement. [fsbProduct product_id=’814′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Much of the movie’s second half focuses largely with the two brothers Simone and Rocco, as the oafish Simone eventually finds success as a boxer, and the family soon moves to a better neighborhood. Meanwhile, Rocco gets drafted by the military, and becomes a successful boxer himself upon his return. Complications arise when Nadia a prostitute, enters their lives and comes between the two brothers. Simone falls in love with Nadia first; however, Rocco eventually becomes the object of her affection. Simone’s jealousy and obsession with Nadia and his rapidly deteriorating behavior ultimately threaten to bring the family to ruin, while the saintly Rocco tries to save his brother. Rocco and His Brothers can be seen quite clearly as an enormous influence on great American gangster films, as themes of Frances Ford Coppola’s The Godfather immediately come into mind, and the tense relationship between the good brother Rocco and the corrupt brother Simone largely influenced Scorsese in his development of such character’s in Mean Streets, and obviously Raging Bull. The tragic character of Nadia makes for one of the most fascinating and tragic female characters in the history of film, as she clearly chooses to be degraded and abused by Simone, as it is her only way of expressing her deep love and anguish for Rocco and of his recent rejection of her.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Rocco and his Brothers Visconti” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Rocco and his Brothers is one of the most operatic melodrama’s of all time, involving a modern Italian family and their personal experiences when moving to the city of Milan one cold winter. Italian director Luchino Visconti was an aristocrat, a homosexual, a Marxist, and a director of theater and opera, becoming one of the major influences in the Italian neo realism movement. He had a love and respect for tradition, decadence, and seamy social realism, as the story of Rocco and his Brothers had an obvious undercurrent of flamboyant characterizations and subtle homoerotic that Visconti never quite reconciles. Following the death of her husband, Rosaria Parondi decides to pick up and move to the city of Milan along with four of her sons: Simone, Rocco, Ciro, and Luca; while Vincenzo, the eldest of the brothers has already established himself there. Unfortunately their timing couldn’t be worse, as they arrive on the night of Vincenzo’s engagement party with the beautiful Ginetta (Claudia Cardinale), whose home he has made welcome. The two families take an instant dislike to each other, and the night ends up horribly as the Parondi family stalk out, and Vincenzo’s engagement is temporary broken. The story is divided into chapters focused loosely on each brother, as the movie chronicles the Parondi’s struggle to get by in Milan, while the brothers take odd jobs and the family endures life in a cramped tenement. [fsbProduct product_id=’814′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Much of the movie’s second half focuses largely with the two brothers Simone and Rocco, as the oafish Simone eventually finds success as a boxer, and the family soon moves to a better neighborhood. Meanwhile, Rocco gets drafted by the military, and becomes a successful boxer himself upon his return. Complications arise when Nadia a prostitute, enters their lives and comes between the two brothers. Simone falls in love with Nadia first; however, Rocco eventually becomes the object of her affection. Simone’s jealousy and obsession with Nadia and his rapidly deteriorating behavior ultimately threaten to bring the family to ruin, while the saintly Rocco tries to save his brother. Rocco and His Brothers can be seen quite clearly as an enormous influence on great American gangster films, as themes of Frances Ford Coppola’s The Godfather immediately come into mind, and the tense relationship between the good brother Rocco and the corrupt brother Simone largely influenced Scorsese in his development of such character’s in Mean Streets, and obviously Raging Bull. The tragic character of Nadia makes for one of the most fascinating and tragic female characters in the history of film, as she clearly chooses to be degraded and abused by Simone, as it is her only way of expressing her deep love and anguish for Rocco and of his recent rejection of her.

PLOT/NOTES

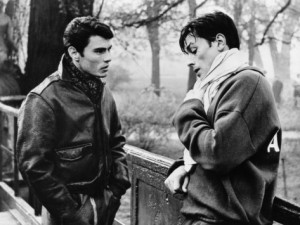

In Milan one cold winter right arrives the Parondi family. Mother Rosaria (Katina Paxinou) apprehensively shepherds four of her five sons from the rail station. They are Simone (Renato Salvatori), Rocco (Alain Delon), Ciro (Max Cartier) and Luca (Rocco Vidolazzi). They’re on their way to the meet oldest son Vincenzo (Spiros Focas), who has already established himself in Milan. “Look at the windows. The light! Looks like a dream!”

Immediately when arriving to Vencenzo’s home Mother Rosaria notices Vincenzo is not wearing black for his deseaced father, and Vencenzo says, “But tonight this is Ginetta. I wrote you that we got engaged, didn’t I? And you came just in time to give us your approval.” It is the night of Vincenzo’s engagement party to the beautiful Ginetta (Claudia Cardinale), whose home and family Vencenzo has been made welcome. But the two mothers take an instant dislike to each other, and the Parondis stalk out, and Vincenzo’s engagement is temporarily broken. “Let’s go. Let’s leave this place. You’re the same breed,” Rosaria rudely says to Ginetta.

That evening Vincenzo goes to talk with his friend Armondo as he is unsure what to do with his mother and the rest of his family. “How am I supposed to take care of the whole family? Where can they stay and who’s gonna pay for that?” Armondo offers the idea of simply to pay the rent for a few months, then stop paying, and get evicted. That way they can find public housing. It is not available, of course, to those who are homeless in the first place: “You have to be evicted,” he tells Vincenzo.

Their living quarters improve as mother and sons move into a bleak basement flat and are overjoyed one morning when it is snowing, because that means work shoveling the streets. Rosaria wakes all her children up to get dressed and have breakfast. In the street Ginetta pulls Vincenzo aside and asks why she doesn’t see him anymore ever since his family moved into town.

One day Vincenzo meets the neighbor and prostitute Nadia (Annie Girardot) who is trying to hide from her father. Simone helps her hide for a bit, by inviting her into his mother’s home. Nadia is introduced to the rest of the brothers and she asks, “Your from the south, aren’t you? Why did you come here to Milan?” Rocco says they shoveled the snow this morning and are still in the middle of finding work. Nadia uses the restroom and Rosaria asks Vincenzo what he was thinking inviting her inside, because she could be a whore. Vincenzo decides to go get the police as Nadia escapes their home using the bathroom window.

Meanwhile, Simone is spotted as promising by a boxing promoter, a snaky and sexually ambivalent man. “Teeth like a wolf, but too much nicotine,” the promoter says. The promoter eventually approaches Simone (rather unsubtly in the shower room) and propositions the naked young boxer-in-trainer with the promise of a champ’s career hanging in the air.

After Simone’s first successful fight Ginetta’s brothers begin to fight Vincenzo outside the stadium, and the other brothers rush out to help him. Simone is the last to make it outside after the fight breaks out and he catches Nadia in the parking lot. She seduces him for a night out, while the promoter watches from in his car.

Simone decides to skip out on boxing practice for a weekend trip to the seaside with Nadia. He visits a laundry matt where Rocco is employed at and steals a shirt just to wear for the day. Rocco goes to the gym to lie for Simone and say he is sick which greatly upsets the promoter. The coach then decides to take Rocco under his wing. The coach asks Rocco to be on guard for his brother Simone and to come and leave with him daily and to keep him away from certain people. “Boxing is a serious profession. That you can only do leading a healthy life. It’s morals that make a good athlete, understand” says the coach. “Women, cigarettes, drinking and many other things…You just can’t do them, no, you just can’t.”

After stealing the shirt Simone spends the day with Nadia taking a trip to the seaside. While the two are spending time together, Simone is talking about sacrificing himself to make it in boxing. “What does that have to do with me,” Nadia asks lighting up a cigarette. Nadia than says, “We need to talk. We’re not married. We see each other occasionally, but we could also not see each other for a year, and there’s no plan commitment.” A security guard is ordered to remove Nadia off the property, (probably because she is known to have prostituted herself at that location before) and Simone makes a fuss.

Later that evening Simone returns the shirt he stole to the owner and she is furious he took advantage of her trust. “Are you crazy! Don’t laugh! Come here, you think you’re cute, asking for favors that you don’t deserve. Taking advantage of the situation to steal and acting clever on top of all that! Thief!” Simone takes advantage of the owner and forces himself upon her.

During the evening Nadia picks up Rocco and tells him to tell her brother that it is over between her and Simone and that she can’t accept anymore of Simone’s gifts. Rocco returns home and tells his brothers that he received his pink notice of enlisting in the Army. Rocco tells Simone that Nadia wants nothing to do with him, and Simone is furious.

While Rocco is drafted in the military he receives letters from his mamma at home letting him know that Vincenzo married Ginetta and is living with her, and Simone is continuing to box.

While during military service Rocco runs into Nadia and she offers him a cup of coffee. The two chat and Rocco talks about a friend his family knew in the country before moving out to the city: “About my age, but poor, poorer than you can imagine. So, one day, they gave them a piece of land to cultivate. But the earth was so hard they would break their arms trying to pull anything out of it. And it took half a day just to walk there. So one day, these good Christians revolted. They were put in handcuffs and brought to prison in Matera, Potenza. What can you do? Things from my country.” Nadia has deep affection for Rocco and says, “That’s why you all escaped from the north.” Nadia asks what Rocco thinks of her and he says, “You have to forgive me, I don’t know why. But I feel sorry for you.”

After Rocco military service he arrives home to find no one there besides his mother. His mamma tells Rocco that everyone is at Vincenzo’s sons baptism. Rocco talks his mamma to come along to see the baby and the family happily reunites.

At the gym Simone is suggesting he needs to spare with better coach. He asks to spare with his little brother Rocco and the coach is astonished how well Rocco can move within the ring. Coach says to Simone, “Simone, listen closely. If you don’t watch out he’ll soon take your place.”

Rocco is now secretly dating Nadia as Simone is slowly on the road to self-destruction. Simone is filled with low self-esteem, proud of his wins but negligent of his training. Rocco tells Signor Cerri that Simone hasn’t been himself since he’s gotten back from being a soldier.

When Simone finds out that Rocco is now seeing Nadia he is enraged. Simone sends several of his thugs out to catch Rocco and Nadia together and when the time is right Simone (who is highly intoxicated) confronts Rocco at a secluded outdoor tryst. Simone tells Rocco to leave his girl alone but Rocco says that Nadia isn’t his girl and that he hasn’t seen Nadia in over two years now. Simone calls out his thugs they hold Rocco down and force him to watch Simone rape Nadia as he says, “I do whatever I like! You want to know how she is, your Nadia? I’ll show you how to make love!” Simone takes off Nadia’s panties and throws them at Rocco saying, “Rocco! Smell them, if you have the courage!”

Afterward the rape Simone says to Rocco, “So now you’ve learned the lesson. We’ll settle the rest at home. From man to man!” Rocco says, “you’re disgusting,” and Simone asks him to fight one on one. Beaten up and bloody Rocco goes to see his oldest brother Viscenzo, and asks if he can stay with him.

The next few day Rocco meets up with Nadia to break it off with her, but she truly loves him saying, “You reached out for me. Convinced me that the life I led was monstrous. I learned to love you. And now, because of this bastard’s meanness…Who wanted to humiliate me in front of you…To lump us in with him…all of a sudden, nothing is true anymore. What was right and fine yesterday, is a crime today.” Rocco says they’re both guilty, him more than her, and he asks Nadia to return to Simone, because only she can help him. Rocco tells her they cannot see each other anymore and Nadia yells out, “I hate you, I hate you, I hate you!!”

Nadia later arrives at a social gathering to confront Simone and inform him that she was told to return to him because he the poor thing is unhappy and needs help and he pathetically needs her.

Meanwhile Rocco is now becoming a successful boxer, as his next defeat in the ring greatly frightens him as he tells Ciri, “You, see, Ciro, it was an easy victory for me. Because it wasn’t him that I was fighting. As if I was fighting someone else, moving all this hatred in me. All this hatred I had accumulated without even knowing. You don’t know how ugly this is.”

Ciro is now seriously dating a girl, and Mother Rosaria is worried about all her sons saying to Rocco, “Is it my fault that all this is happening? Was I wrong to bring my songs to the city, all so handsome, big and strong, so they could become rich, instead of following their father’s footsteps on that cursed land that made him die a thousand deaths before he closed his eyes forever?” Mother Rosaria persists in dreaming that her sons will live together under her roof, but Vincenzo marries Ginetta, while Rocco leaves home to live with Vincenzo. Meanwhile Simone has Nadia move in and his mother is expected to shelter and feed both of them while Simone smokes and lays around the house with Nadia drunk. Rocco tell his mother she did nothing wrong and comforts her.

Rocco confronts Simone and asks him to have some respect for mama and whom he brings home. Ciro is still living at home and is extremely angry with Simone as he says to Rocco, “Think about our mother, she has to make this woman’s bed every morning. Brother or not it doesn’t make a difference to me anymore. Look, Ro, we’re like seeds from the same tree, seeds that have to become a healthy plant. If one amidst us is rotten, we’ll, we have to separate it from the rest just like when we clean the lentils from Mamma.” Rocco says to Ciro, “Simone didn’t change. He’s just demoralized, his self-esteem is shattered. Imagine if we would have never left home.”

Rocco’s boxing career advances steadily, even though he despises the sport. Financially, he has little choice but to continue as the rest of the family depend on him. The sleazy promoter is furious at Simone and of his downfall. “Ah, the champion! I knew you were gonna end up like this. As a boxer, your finished. And as a man. Only someone like me can have a certain interest for this wreck that you’ve become.”

The promoter lures Simone back to his place and beats up Simone, and the next morning the police arrive at Rosaria’s to look for Simone. Ciro agrees to go to the station with the cops if they tell him what its all about.

In the meantime Nadia is staying at Rosaria and she doesn’t even know why Simone didn’t come home but his mother blames Nadia. Nadia gets ready to leave saying to his mother, “Don’t worry! I’m leaving! Why should I stay? Tell me. Simone has gone all the way and that’s exactly what I wanted! I can leave satisfied now.”

Rocco plans to pay off Simone’s debt, as the boxing coach offers Rocco a big amount of money if he signs with him for ten years. Rocco agrees to it saying to his family, “Do you have a better idea to save Simone from his fate.” Rocco gives the money he receives to Simone informing him to leave town and not come back.

Two fights, are intercut, which involve Rocco being declared champion and of Simone brutally killing Nadia. “You have no idea how I despise you,” Nadia tells Simone while the two are alone together. “You’re not a man, you’re an animal. Everything you touch becomes filthy…repellent…vulgar. I don’t ever want to see you again. Never, you hear me? You destroyed the only good thing that happened to me. I’m going back to jail you know. Now I can finally split all the disgust I feel for you. Do what you want to me. I don’t give a damn.” Nadia opens her arms wide welcoming Simone to stab her to death, while Rocco wins the boxing match.

Rosaria says, “Love live Rocco! But I’ll be really happy on the day that my five sons are all reunited around this table, like five fingers on a hand. To your success. Tonight we should all be joyful. To Rocco.” The Parondi family celebrate Rocco’s winning at her home as neighbors pour out on to the balconies to cheer Rocco as new champion.

Rocco gives a speech to his younger brothers Ciro and Luca saying: “There’ll come a day, of course, it’s gonna be a while that I’ll go back to the country. And if I don’t, maybe another one of us. Luca, you for example, will. Remember, Luca, that our country is the land of olive trees. Of moonshine and rainbows. Do you remember, Vince? Remember that a mason, when he starts to build a house, he throws a stone on the shadow of the first person that passes by. You have to make a sacrifice, to make the house become solid.”

After the celebration Simone returns home in wretched defeat to the always forgiving arms of his mother. Rosaria is relieved all her sons are finally together, but Rocco pulls Simone into the other room asking him why he is there. When he notices blood on Simone, his brother tells Rocco that he had killed Nadia. “Are you happy, champion?” Simone says. “It’s over, Roc.”

Rosaria starts losing her reasoning as well stating that Simone got rid of his disgrace. Ciro decides to leave to get the authorities as Rocco runs out to stop him, but it’s too late. “It’s all over now,” Rocco says.

After Simone’s arrest Luca is angry at Ciro for reporting Simone. While Ciro is working at the Alfa-Romeo assembly line he his youngest brother Luca: “Once you’re older you’ll understand how little justice you do me. Nobody loved Simone the way I did! When we got to Milan, I was a little older than you and Simone explained everything to me that Vincenzo didn’t get. He told me that down in the south, these good Christians live like poor animals, knowing only hard work and obedience. But also that everyone should get by without being a slave to anybody and without forgetting about his own duties. But Simone forgot about that and that’s why he ended up so miserably. He ruined himself and brought shame on all of us. He caused such pain to Rocco, and you, too Luca, our little one, whom he taught. Simone had roots, but he got poisoned by bad herbs. And it’s wrong for Rocco to be so good and generous. He’s a saint. But this is the real world. He doesn’t defend himself. He always forgives everyone but that’s not always right!” Luca says, “If Roc goes back to the country, I want to go with him.” Ciro says, “I don’t think he’ll make it back there. You might go back alone one day. There, too, our lives would change. Down there they are realizing that the world is changing, too. Some say that such a world would not be better. But I believe Luca. I know, your life will be more just and honest.”

After Simone’s arrest Luca is angry at Ciro for reporting Simone. While Ciro is working at the Alfa-Romeo assembly line he his youngest brother Luca: “Once you’re older you’ll understand how little justice you do me. Nobody loved Simone the way I did! When we got to Milan, I was a little older than you and Simone explained everything to me that Vincenzo didn’t get. He told me that down in the south, these good Christians live like poor animals, knowing only hard work and obedience. But also that everyone should get by without being a slave to anybody and without forgetting about his own duties. But Simone forgot about that and that’s why he ended up so miserably. He ruined himself and brought shame on all of us. He caused such pain to Rocco, and you, too Luca, our little one, whom he taught. Simone had roots, but he got poisoned by bad herbs. And it’s wrong for Rocco to be so good and generous. He’s a saint. But this is the real world. He doesn’t defend himself. He always forgives everyone but that’s not always right!” Luca says, “If Roc goes back to the country, I want to go with him.” Ciro says, “I don’t think he’ll make it back there. You might go back alone one day. There, too, our lives would change. Down there they are realizing that the world is changing, too. Some say that such a world would not be better. But I believe Luca. I know, your life will be more just and honest.”

NEOREALISM

Italian Neorealism came about as World War II ended and Benito Mussolini’s government fell, causing the Italian film industry to lose its center. Neorealism was a sign of cultural change and social progress in Italy. Its films presented contemporary stories and ideas, and were often shot in the streets because the film studios had been damaged significantly during the war.

The neorealist style was developed by a circle of film critics that revolved around the magazine Cinema, including Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini, Giuseppe De Santis and Pietro Ingrao. Largely prevented from writing about politics (the editor-in-chief of the magazine was Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito Mussolini), the critics attacked the white telephone films that dominated the industry at the time. As a counter to the popular mainstream films, including the so-called “White Telephone” films, some critics felt that Italian cinema should turn to the realist writers from the turn of 20th century.

Both Antonioni and Visconti had worked closely with Jean Renoir. In addition, many of the filmmakers involved in neorealism developed their skills working on calligraphist films (though the short-lived movement was markedly different from neorealism). In the Spring of 1945, Mussolini was executed and Italy was liberated from German occupation. This period, known as the “Italian Spring,” was a break from old ways and an entrance to a more realistic approach when making films. Italian cinema went from utilizing elaborate studio sets to shooting on location in the countryside and city streets in the realist style.

The first neorealist film is generally thought to be Ossessione by Luchino Visconti in 1943. Neorealism became famous globally in 1946 with Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, when it won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival as the first major film produced in Italy after the war.

Most neorealism films are generally filmed with nonprofessional actors–although, in a number of cases, well known actors were cast in leading roles, playing strongly against their normal character types in front of a background populated by local people rather than extras brought in for the film.

They are shot almost exclusively on location, mostly in run-down cities as well as rural areas due to its forming during the post-war era, no longer being constrained to studio sets. The topic involves the idea of what it is like to live among the poor and the lower working class. The focus is on a simple social order of survival in rural, everyday life. Performances are mostly constructed from scenes of people performing fairly mundane and quotidian activities, devoid of the self-consciousness that amateur acting usually entails. Neorealist films often feature children in major roles, though their characters are frequently more observational than participatory.

Open City established several of the principles of neorealism, depicting clearly the struggle of normal Italian people to live from day to day under the extraordinary difficulties of the German occupation of Rome, consciously doing what they can to resist the occupation. The children play a key role in this, and their presence at the end of the film is indicative of their role in neorealism as a whole: as observers of the difficulties of today who hold the key to the future.

Many of the films involved Post-synch sound/dubbing employing conversational speech, and local dialects. They also included funtional rather than ostentatious editing that would draw attention to itself, as shots were organized loosely. Many neorealism films involved stories that were episodic, elliptical, or organic in structure. Plot were preferable not a tight framework of cause and effect, but a more fluid relationship between scenes which approximated how events would occur in real life.

Many of the films had a sense of a documentary impulse & immediacy in filming, shifting away from the pretense of studio stories. It wanted to be a cinema that attended to the details and trials of everyday life, of the material experience of average people in difficult situations. It also had a concern with the lives of working-class people and a social commitment and humanist point of view to contemporary stories that spoke to the historical present. Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 film Bicycle Thieves is also representative of the genre, with non-professional actors, and a story of a ‘everyday man’ and his hardships of working-class life after the war.

Italian Neorealism rapidly declined in the early 1950s. Liberal and socialist parties were having a hard time presenting their message. Levels of income were gradually starting to rise and the first positive effects of the Ricostruzione period began to show. As a consequence, most Italians favored the optimism shown in many American movies of the time. The vision of the existing poverty and despair, presented by the neorealist films, was demoralizing a nation anxious for prosperity and change. The views of the postwar Italian government of the time were also far from positive, and the remark of Giulio Andreotti, who was then a vice-minister in the De Gasperi cabinet, characterized the official view of the movement: Neorealism is “dirty laundry that shouldn’t be washed and hung to dry in the open.”

Italy’s move from individual concern with neorealism to the tragic frailty of the human condition can be seen through Federico Fellini’s films. His early works Il bidone and La Strada are transitional movies. The larger social concerns of humanity, treated by neorealists, gave way to the exploration of individuals. Their needs, their alienation from society and their tragic failure to communicate became the main focal point in the Italian films to follow in the 1960s. Similarly, Antonioni’s Red Desert and Blow-up take the neo-realist trappings and internalize them in the suffering and search for knowledge brought out by Italy’s post-war economic and political climate.

Neorealism screenwriter Cesare Zavattini said, “film should address not ‘historical man’ but the ‘man without a label.’ I dare to think that other peoples, even after the war, have what they continued to consider man as a historical subject, as historical material with determined almost inevitable actions…For them everything continued, for us, everything began. For them the war had been just another war, for us, it had been the last war…The reality of buried under the myths slowly reflowered. the cinema began its creation of the world. Here was a tree, here, an old man, here, a house, here a man eating, sleeping, a man crying…The cinema should accept unconditionally, what is contemporary. Today, today, today.”

French film critic Andre Bazin on neorealism: “No more actors, no more story, no more sets, which is to say that the perfect aesthetic illusion of reality, there is no more cinema.”

In the period from 1944–1950, many neorealist filmmakers drifted away from pure neorealism and into a period of “rosy neorealism” of Italian films of the 1950’s. Some directors explored allegorical fantasy, such as de Sica’s Miracle in Milan, and historical spectacle, like Senso by Visconti. This was also the time period when a more upbeat neorealism emerged, which produced films that melded working-class characters with 1930s-style populist comedy, as seen in de Sica’s Umberto D.

There are different debates on when the Neorealist period began and ended. Some claimed it ended in 1948, with the shift in power from the left to the centrist Christian Democrat Party and with the inclusion of Italy in the Marshall Plan, which began to subsidize the film industry once more. Many claimed that the cycle ended with De Sica’s Umberto D in 1952.

Robert Kolker suggests a useful way of thinking about “two Neorealisms. 1) on the one hand a group of films made between 1945 & 1955, and 2) on the other Neorealism as an idea, an aesthetic, a politics…both a form of praxis and an ideal to aspire to.”

Irrelevant Actions were an aesthetic that neorealism provided. Andre Bazin essay on Umberto D saying, “the most beautiful sequence in the film, the awaking of the little maid, rigorously avoids and dramatic italicizing. The young girl gets up, comes and goes in the kitchen, hunts down ants, grinds the coffee…and all these ‘irrelevant’ actions are reported to us with meticulous temporal continuity.”

More contemporary theorists of Italian Neorealism characterize it less as a consistent set of stylistic characteristics and more as the relationship between film practice and the social reality of post-war Italy. Millicent Marcus delineates the lack of consistent film styles of Neorealist film. Peter Brunette and Marcia Landy both deconstruct the use of reworked cinematic forms in Rossellini’s Open City. Using psychoanalysis, Vincent Rocchi characterizes neorealist film as consistently engendering the structure of anxiety into the structure of the plot itself.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

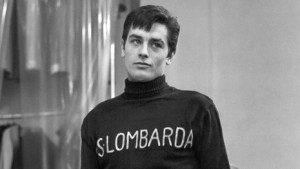

The title for Rocco and His Brothers is a combination of Thomas Mann’s Joseph and his Brothers and the name of Rocco Scotellaro, is of an Italian poet who described the feelings of the peasants of southern Italy. Set in Milan, the film tells the story of an immigrant family from the South and its disintegration in the society of the industrial North. The film stars the legendary Alain Delon from such acclaimed films as Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai and Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’ Eclipse. Rocco and His Brothers was one of actress Claudia Cardinale’s early roles before she became internationally known, and the film’s score was composed by the legendary Nino Rota.

Italian director Luchino Visconti was an aristocrat, a homosexual, a Marxist, and a director of theater and opera, becoming one of the major influences in the Italian neo realism movement. Visconti started out with a noir film called Ossessione, which is an Italian retelling of James M. Cain’s pulp crime classic The Postman Always Rings Twice. Then he directed La terra trema which is a neorealism classic that explores the lives of fishermen at the mercy of greedy wholesalers in rural Sicely. Senso is a tragic story about an Italian Countess who betrays her entire country for a self-destructive love affair with an Austrian Lieutenant, and his swan song Death in Venice tells the poignant story of a composer utterly absorbed in his work. And yet it was Visconti’s love for tradition and of the slow dying of aristocracy which was explored in his epic masterpiece The Leopard, which is looked at by many critics as the Italian Gone with the Wind, and one of the greatest films ever made.

And yet it is Rocco and His Brothers which brings together many of Visconti’s different styles and themes, as they all struggle for time and space on his epic three-hour canvas. The word ‘operatic’ is used for Rocco and His Brothers, and there really isn’t a better way to describe the film. The film has so many plot elements that occur and several different themes that are explored, that it’s hard to sum up the film with just a few sentences. Visconti had a love and respect for tradition, decadence, and seamy social realism, as the story of Rocco and his Brothers had an obvious undercurrent of flamboyant characterizations and subtle homoerotic that Visconti never quite reconciles. The love that is expressed between the brothers and the tension between Simone and Rocco, especially the moments when the two are physical with one another give off slightly sexual hints, and as much as the story conceals those repressed themes, they are there. The most obvious sequence is with the snaky and sexually ambivalent boxing promoter, as he propositions Simone while Simone is in the shower room.

Rocco and His Brothers is shot in beautiful stark black and white, as many of the sequences that involve the family struggling for work bring upon themes of the Italian neo realism movement, including ending the film ambiguously with no substantive resolution, but with clouds of doom hanging over the family. The brilliance in Rocco and his Brothers is its gritty portrait of life in working-class Milan in 1960, as the film was shot in the housing projects and streets of the city. These authentic location shootings is a prime example of the power of neo realism as the film expresses historical interest on how people lived and what places looked like at a time and place in Italian history. The film can be seen as being an enormous influence on the American gangster films, most famously with Frances Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Rocco projects the early character traits of the pure Michael Corleone and of his enlistment in the military, as a way to get away from his family. The tense, and rocky relationship between Rocco and Simone clearly inspired Scorsese’s characters of Charlie (Harvey Keitel) and Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) in Mean Streets, as the film is almost unimaginable without the precedence of Rocco and His Brothers. The boxing sequences and the violent, cowardly and rageful jealousy that encompasses the character of Simone, which ultimately effects the relationship between his brothers, are ideas that Scorsese explored in more disturbing detail in his masterpiece Raging Bull.

They’re many classic sequences throughout the film, one sequence involves the family becoming overjoyed when it starts snowing one morning, and because of this they eagerly get up and get dressed to start shoveling the streets. The other sequence involves the brutal rape of Nadia, after Simone explodes with jealously when making the discovery that his brother Rocco is secretly romantically involved with her. The horrifying moment when Simone forces his brother to watch him rape Nadia is disturbing and was quite controversial at the time of the films release. The other sequence which made the film highly controversial is Nadia’s murder near the end of the film. The film brilliantly intercuts between two different fight sequences: One involves Rocco being declared champion in the boxing ring and the other is of Simone brutally stabbing and killing Nadia. Because of these scenes of Nadia’s rape and murder, the film was seized during the shooting and Visconti was asked to delete those two sequences. Visconti was not vindicated until a court judgment in 1966.

The film critic for The New York Times, Bosley Crowther wrote, “A fine Italian film to stand alongside the American classic, The Grapes of Wrath, opened last night …It is Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers, and it comes here garlanded with laurels that are quite as appropriate in this context as they are richly deserved…Signor Visconti has clearly conceived his film and that is what his brilliant handling of events and characters makes one feel. There’s a blending of strong emotionalism and realism to such an extent that the margins of each become fuzzy and indistinguishable…Alain Delon as the sweet and loyal Rocco…is touchingly pliant and expressive, but it is Renato Salvatori …who fills the screen with the anguish of a tortured and stricken character. His raw and restless performance is overpowering and unforgettable…and the French actress Annie Girardot is likewise striking as the piteous prostitute…”

The tragic character of Nadia is the most fascinating parts of Rocco and His Brothers, as she brings to the story a burst of energy and unpredictable spontaneity. She clearly is a victim of physical and mental abuse, and violence is the only lifestyle she knows. She allows weak and insecure people to control her life, which is why she allows Simone to degrade and abuse her. Rocco is self-confident, righteous, and pure, and encompasses all the things his brother Simone wants, but does not have. Simone is weak and negligent in his training, smoking and drinking too much, causing himself to throw away his career as a boxer. Rocco has the potential to be the champion that Simone cannot be, it’s just not the future Rocco wants. When Nadia begins to date a man like Rocco, his strength gives her the will to want to change and begin to love and respect herself. But after his rejection she decides to start dating Simone again, only out of spite and contempt for Rocco. I can understand how hurtful and cruel it was for Rocco to leave her at a time where she needed him the most. And yet she is clearly a selfish person to allow Simone to self-destruct while living under the roof of their mother. That Nadia would not only allow that to happen, but to cruelly stand by and watch Simone tear his family apart and torment his own mother makes her as guilty as Simone. Nadia is cruelly abused by her love for Simone, drops from high style to degradation in her career as a prostitute, and her last meeting with Simone cries out for operatic arias to express their feelings. In some ways it seems that she is begging Simone to kill her, and she greets Simone’s violent attack with open arms, as if accepting her tragic fate. The melodrama in the film shouldn’t work, but it does and hits each melodramatic mark perfectly, as the outpouring of emotion, pain, and exhilarating drama is quite similar to the witnessing of an opera. The end of the film is quite tragic as the damage that was done to the Parondi family is unrepairable and can never be mended again. They’re two speeches in the film that clearly express the strengths of family ties that Visconti is exploring. One is near the end of the film where Ciro, who has a job on the Alfa-Romeo assembly line, speaks with his youngest brother Luca, on his duty to his family and his ties to the south. The other speech is the one Rocco gives to both of his younger brothers the night after his victory as boxing champion. His speech sums up what I believe Visconti is trying to say with the film: “Remember, Luca, that our country is the land of olive trees. Of moonshine and rainbows. Do you remember, Vince? Remember that a mason, when he starts to build a house, he throws a stone on the shadow of the first person that passes by. You have to make a sacrifice, to make the house become solid.”

The tragic character of Nadia is the most fascinating parts of Rocco and His Brothers, as she brings to the story a burst of energy and unpredictable spontaneity. She clearly is a victim of physical and mental abuse, and violence is the only lifestyle she knows. She allows weak and insecure people to control her life, which is why she allows Simone to degrade and abuse her. Rocco is self-confident, righteous, and pure, and encompasses all the things his brother Simone wants, but does not have. Simone is weak and negligent in his training, smoking and drinking too much, causing himself to throw away his career as a boxer. Rocco has the potential to be the champion that Simone cannot be, it’s just not the future Rocco wants. When Nadia begins to date a man like Rocco, his strength gives her the will to want to change and begin to love and respect herself. But after his rejection she decides to start dating Simone again, only out of spite and contempt for Rocco. I can understand how hurtful and cruel it was for Rocco to leave her at a time where she needed him the most. And yet she is clearly a selfish person to allow Simone to self-destruct while living under the roof of their mother. That Nadia would not only allow that to happen, but to cruelly stand by and watch Simone tear his family apart and torment his own mother makes her as guilty as Simone. Nadia is cruelly abused by her love for Simone, drops from high style to degradation in her career as a prostitute, and her last meeting with Simone cries out for operatic arias to express their feelings. In some ways it seems that she is begging Simone to kill her, and she greets Simone’s violent attack with open arms, as if accepting her tragic fate. The melodrama in the film shouldn’t work, but it does and hits each melodramatic mark perfectly, as the outpouring of emotion, pain, and exhilarating drama is quite similar to the witnessing of an opera. The end of the film is quite tragic as the damage that was done to the Parondi family is unrepairable and can never be mended again. They’re two speeches in the film that clearly express the strengths of family ties that Visconti is exploring. One is near the end of the film where Ciro, who has a job on the Alfa-Romeo assembly line, speaks with his youngest brother Luca, on his duty to his family and his ties to the south. The other speech is the one Rocco gives to both of his younger brothers the night after his victory as boxing champion. His speech sums up what I believe Visconti is trying to say with the film: “Remember, Luca, that our country is the land of olive trees. Of moonshine and rainbows. Do you remember, Vince? Remember that a mason, when he starts to build a house, he throws a stone on the shadow of the first person that passes by. You have to make a sacrifice, to make the house become solid.”