Ran (1985)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Ran Kurosawa” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]

Throughout his career William Shakespeare’s stories have always fascinated the legendary director Akira Kurosawa, and he has adapted many of his stories into Japanese Samurai culture. He translated Macbeth into his samurai film Throne of Blood and the classic story of Hamlet into his noir film The Bad Sleep Well. Then in 1975 he wanted to make a samurai epic that was based on the story of King Lear, but no one would help him finance it. Today we consider Kurosawa to be one of the greatest, if not the greatest director in cinema history, but for years he didn’t get the honor or respect he deserved. Earlier in his career he created some of the greatest of films including The Seven Samurai, Rashomon, Yojimbo, Ikiru, The Hidden Fortress and High and Low. Then times grew hard for the film director, as his own country condemned him as being ‘too western’ and old fashioned, and he sadly had to start begging for financing to make movies. Years passed and the director finally found financing in Russia for his masterpiece Dersu Uzala, and even though it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film, it was a failure at the box office. Five years later he made the medieval epic Kagemusha finally with the support of such directors as George Lucas and Frances Ford Coppola, which Kurosawa considered was a ‘rehearsal’ before Ran. He had filled notebooks full of storyboard drawings of costumes and locations of scenes of his King Lear adaptation, and with the help of a French producer Serge Siberman who has helped out other great film directors such as Luis Bunuel; Kurosawa finally found the funds to make the film. While Kurosawa’s earlier samurai epics were more adventurous, lighthearted, humorous, and exciting, Ran was cold, remote, more violent, and horrifying. [fsbProduct product_id=’809′ size=’200′ align=’right’]They’re several parallels to the story of King Lear in Ran, including an old king who is driven mad after unwisely dividing his kingdom into three parts, (among sons, not daughters). There is a body guard and protector and a loyal fool to keep the king company. And they’re the kings sons whose greed, betrayal and lust for power, lead to bloodshed, which is all perfectly orchestrated by the evil Lady Kaede, the seductress who incites the war for personal vengeance, purposely plunging all of them into hell. Kurosawa once stated “Hidetora is me,” and there is some evidence in the film that Hidetora serves as a stand-in for Kurosawa. A lot of critics have stated that Ran was a story Kurosawa couldn’t have made in his earlier years as a filmmaker, and that the bleak story of the aging Hidetora was a character Kurosawa could be able to relate to more in his later years of life. Throughout his later years Kurosawa became more preoccupied with the themes of death, mortality, and had a more pessimistic outlook on human nature and justice. It was also in his later years that his eyesight was beginning to fail him and he even attempted suicide. Even though he announced Ran was to be his very last film he made one more titled Dreams; but many consider Ran (in English means ‘Chaos’) to be his swan song and one of the greatest films in the world, as it is not only looked at as Kurosawa’s most personal film, but the film that closely reflects the man himself.

Throughout his career William Shakespeare’s stories have always fascinated the legendary director Akira Kurosawa, and he has adapted many of his stories into Japanese Samurai culture. He translated Macbeth into his samurai film Throne of Blood and the classic story of Hamlet into his noir film The Bad Sleep Well. Then in 1975 he wanted to make a samurai epic that was based on the story of King Lear, but no one would help him finance it. Today we consider Kurosawa to be one of the greatest, if not the greatest director in cinema history, but for years he didn’t get the honor or respect he deserved. Earlier in his career he created some of the greatest of films including The Seven Samurai, Rashomon, Yojimbo, Ikiru, The Hidden Fortress and High and Low. Then times grew hard for the film director, as his own country condemned him as being ‘too western’ and old fashioned, and he sadly had to start begging for financing to make movies. Years passed and the director finally found financing in Russia for his masterpiece Dersu Uzala, and even though it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film, it was a failure at the box office. Five years later he made the medieval epic Kagemusha finally with the support of such directors as George Lucas and Frances Ford Coppola, which Kurosawa considered was a ‘rehearsal’ before Ran. He had filled notebooks full of storyboard drawings of costumes and locations of scenes of his King Lear adaptation, and with the help of a French producer Serge Siberman who has helped out other great film directors such as Luis Bunuel; Kurosawa finally found the funds to make the film. While Kurosawa’s earlier samurai epics were more adventurous, lighthearted, humorous, and exciting, Ran was cold, remote, more violent, and horrifying. [fsbProduct product_id=’809′ size=’200′ align=’right’]They’re several parallels to the story of King Lear in Ran, including an old king who is driven mad after unwisely dividing his kingdom into three parts, (among sons, not daughters). There is a body guard and protector and a loyal fool to keep the king company. And they’re the kings sons whose greed, betrayal and lust for power, lead to bloodshed, which is all perfectly orchestrated by the evil Lady Kaede, the seductress who incites the war for personal vengeance, purposely plunging all of them into hell. Kurosawa once stated “Hidetora is me,” and there is some evidence in the film that Hidetora serves as a stand-in for Kurosawa. A lot of critics have stated that Ran was a story Kurosawa couldn’t have made in his earlier years as a filmmaker, and that the bleak story of the aging Hidetora was a character Kurosawa could be able to relate to more in his later years of life. Throughout his later years Kurosawa became more preoccupied with the themes of death, mortality, and had a more pessimistic outlook on human nature and justice. It was also in his later years that his eyesight was beginning to fail him and he even attempted suicide. Even though he announced Ran was to be his very last film he made one more titled Dreams; but many consider Ran (in English means ‘Chaos’) to be his swan song and one of the greatest films in the world, as it is not only looked at as Kurosawa’s most personal film, but the film that closely reflects the man himself.

PLOT/NOTES

The classic epic begins with an exciting hunting scene with several Samurai Lords and you get a closeup of the main character Lord Hidetora Ichimonji before he makes his kill at a pig with his bow and arrow. After the hunting party you see several samurai’s in lush colorful wardrobes seeing down on the grass having tea. Lord Hidetora announces that the hero of the hunt was Lord Ichimonji and to drink to him. His three sons who are sitting there as well know why the two Lords are there. Lord Ichimonji and Lord Ayabe want Hidetora’s third son Saburo to marry off one of their daughters because it would be good for the two houses.

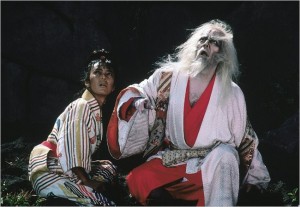

Each of Hidetora’s three sons wears a different color; Saburo his youngest and rebellious where’s blue, Jiro the middle son who is married to Lady Sué where’s red and the eldest son who is married to Lady Kaede is in yellow. They have a jester named Kyoami who entertains them with laughs of song and dance. Hidetora falls asleep on his guests and when the two Lords leave his children are worried because their father is getting old and he never dozed off on guests before. Suddenly their father wakes up and runs at them with a horrible nightmare that he was in a world all alone. Saburo is uneasy about his father’s erratic behavior and later when Hidetora announces to his children and to Lords Fujimaki and Ayabe about him giving up his title to Taro, the eldest; he is not happy.

Taro will receive the prestigious First Castle and become leader of the Ichimonji clan, while Jiro and Saburo will be given the Second and Third Castle. Hidetora will remain the titular leader and retain the title of Great Lord. He then gets up and gives his children an analogy on family bonds by telling his three sons to break an arrow. After they easily snap them in half he gives them three arrows bundled together to snap and once they can’t break them Hidetora says, “A single arrow is easily broken. Not three bundled together.” Saburo angrily takes the bundled arrows and decides to break them over his knee saying, “there are many ways to break even three sticks together.”

Saburo then criticizes the logic of Hidetora’s plan and how his father achieved power through violence and treachery, and yet he foolishly expects his sons to be loyal to him. Hidetora mistakes these comments for a threat; and when his servant Tango comes to Saburo’s defense saying there is truth to his words; Hidetora bans them both off his lands and considers Saburo no longer blood. Later, Fujimaki who had witnessed these events, confronts Saburo and tells him he likes his strength of character and invites Saburo to his dominions to offer him his daughter to marry. Tango is told by Saburo to stay and look out for father knowing certain doom will soon occur.

Following Hidetora’s abdication, Taro’s wife Lady Kaede begins pushing for Taro to take direct control of the Ichimonji clan, and engineers a rift between Taro and Hidetora. Her family was slaughtered years ago by her husbands father and she still holds much hatred and contempt because of it. She purposely starts trouble by asking why her husband handed over the battle standard armor to his father’s men; when he clearly did it as a friendly gesture. She then says, “I suggest you act as a lord,” and Taro decides to ask for the armor back; which causes a huge fight. When Kyoami makes fun of Taro’s new position he is almost attacked by Taro’s guard who is defending his Lord until Hidetora kills him with an arrow from the castle walls.

Taro is not happy of that and announces to see his father right away. When his father arrives he says, “you call this a family meeting?” Lady Kaede is there as well and she says to Hidetora, “Father, won’t you be seated?” He’s offended by his son’s wifes comments replying, “You expect me to sit below you?” Taro then tells his father that he must have forgotten that he has made him head of the house and he didn’t like his father killing one of his men. He says he will let this one ‘pass’ this time and then subsequently demands that Hidetora renounce his title of Great Lord by signing a “covenant.” At first Hidetora says he wont, but he is pressured and eventually does it and then angrily storms out of the castle.

He then travels to Jiro’s castle, who already gotten a letter from Taro saying how he banished father for his erratic behavior. Jiro and his advisor Kurogane talk about wanting to take over his brother’s position. Jiro says, “Just because I was born a year after Taro, am I to grovel all my life at his feet?” When his father finally arrives Hidetora finds Jiro’s wife Lady Sue; who seems unhappy and alone. One of the most touching scenes of the film is Hidetora asking her why she smiles at him and looks at him with no hate when years earlier he burned down her family’s home. You can see shame and regret in Hidertora’s face for what he did to her in the past. She just tells him her brother Tsurumaru tought her not to hate through Buddha and Hidetora is astonished on how loving and forgiving she is.

When Jiro finds his father he tells him he already knows what happened between him and Taro. While speaking with Jiro Hidetora figures out that Jiro is more interested in using him as a pawn in his own power play after Jiro tells him to apologize to Taro. Hidetora says, “Your no different than Taro,” and he and his men decide to leave Jiro’s castle. Now wandering with his men and finding no food in the villages which was abandoned by the peasants, Hidetora comes to the realization that his youngest son Saburo was right, and that greed and power has turned his family against him.

Eventually Tango appears with provisions. In a moment of anger Hidetora orders his escort to burn the villages down but Tango intervenes and Hidetora learns from him that Taro forced the peasants to flee because of Hidetora. Tango advises him that they should go to Lord Fujimaki’s castle because Saburo is there with his new wife. “How could I ever face Saburo now?,” Hidetora asks. Hidetora decides to instead journey to the Third Castle, which had been abandoned after Saburo’s forces followed their lord into exile but Tango and Kyoami do not follow him; believing it’s not safe.

Hidetora and his men take shelter in the third castle only to wake up and see it being ambushed by the combined forces of Taro and Jiro. In the best scene of the film Hidetora watches a horrific massacre of all of his bodyguards getting killed in a gruesome bloody battle. One of his men with several arrows in his front and back says to Hidetora, “my Lord, the enemy is everywhere, inside and out! Hell is upon us!!” The sound goes silent as a powerful music score covers the massacre as Hidetora becomes stunned; watching bloody dead bodies of his men and woman fall full of arrows, several of his concubines stab each other to death in a mutual suicide, a dying man is holding his severed arm and the castle is being set on fire.

Hidetora suddenly becomes in a trance like shock as he sits through this massacre with hundreds of arrows zipping past him. He gets up finally to commit seppuku, however to his dismay, Hidetora’s sword has been broken and he cannot do it. Instead of killing himself, Hidetora has a psychotic breakdown and starts to walk out of the burning castle with everyone else inside already dead. One of the most beautiful shots of the film is him all alone wandering slowly outside the castle walking past Jiro and Taro’s men who are too awe-struck by his transformation to stop him.

As Taro and Jiro’s forces storm the castle, Jiro’s general Kurogane assassinates Taro by shooting him down in the confusion of the battle. Hidetora is discovered wandering in the wilderness by Tango and Kyoami, who along with Saburo remain the only people still loyal to him. They see him in a shocked state smiling at the beauty of flowers while picking them from the fields. “Has he gone mad?” Tango asks and Kyoami says, “In a world gone mad, it’s madness to be sane!”

They take Hidetora refuge in a peasant’s home only to discover that the occupant is Tsurumaru, the brother of Lady Sué (Hidetora’s daughter-in-law), whom Hidetora had brutally ordered blinded years ago. In his mad-like state realizing it is Tsurumaru, Hidetora becomes hysteric with his past demons coming back to haunt him once again. Upon his return from battle, Jiro comforts Lady Kaede because of the death of her husband and brings her a lock of his hair. She questions why Jiro is wearing her husbands armor. He was wearing it out of respect for her husband but now realizing it was rude to wear it, removes it for her. Later at his castle Lady Kaede comes to have a meeting with Lord Jiro. This is my favorite part and one of the most intense scenes of the film.

“They say your father has gone mad.”

“That must please you. Lady Kaede…you must hate my father fiercely for what he did to you and your family…or am I not mistaken?”

“I could say much the same. Lord Jiro too must be pleased. After all, you are head of the Ichimonji clan.” (Lady Kaede leans over to offer him a gift and suddenly leaps at him putting a knife to Jiro’s throat.) “I’m not blind, Lord Jiro! You drove your father mad, murdered your brother and stole his lands! This is for my husband!!”

“Your wrong! It wasnt me! I didn’t kill my brother! Kurogane shot him!”

“Hypocrite!! Would you give the order, then deny the blame? A fine leader you are! You contemptible weakling. Haaaaaahaaaaa!!!! Now it’s my turn to speak the truth. Lord Jiro, I couldn’t care less about my husband’s death. All I care about is myself! I refuse to live as a widow, with my hair cut short, or as a nun with my head shaved! Lord Jiro if you’ll grant my request, I will say nothing of your abominable crimes. If I did I could throw this land into turmoil! What do you say my lord?” (She then leaps on him and starts to kiss him licking the dry blood off his neck.)

They then make love and afterwards she demands that Jiro divorce his wife Lady Sué and marry her instead. When he agrees to it, she also demands that he have Sué killed because she wants no one else to know of his touch. Kurogane is given the order but he does not agree to take a person’s life if there is no reason too. He then publicly disobeys and warns Jiro not to trust Lady Kaede and when she walks in she calmly tells Kurogane, “Lord Kurogane, I trust the second castle has ample stores of salt? You’ll need to bring the head back wrapped in salt, otherwise in the heat…”

One of the only humourous scenes in the film is when Kurogane comes back and hands Lady Kaede the supposed head and when opening up the wrapping to examine it, Lady Kaede finds a fox head from a shrine. Kurogane sarcastically says, “Lady Sué must have been a fox in disguise! A clever fox indeed!” This infuriates Lady Kaede and she storms out of the room. In the next scene you realize that Lord Kurogane had instead warned Lady Sué to flee, and to reach her former home, a ruined castle that Hidetora had destroyed in an earlier war.

Meanwhile, Hidetora’s party hides out in the remains of the same castle and at one point Tango chases two men from Hidetora’s bodyguards who he discovers had betrayed their former master. As Tango fights and kills the two traitors, one of them says before dying that Jiro killed his brother Taro and is talking of trying to hunt down and kill Hidetora. Since Hidetora is not in the right state of mind he refuses with terror to meet up with his youngest son Saburo who can protect him; so Tango rides off to bring Saburo to Hidetora instead, while Kyoami stays to assist the mad man. In his madness Hidetora is haunted by horrific visions of the people he destroyed in his quest for power. The insanity finally becomes too much for him to bear; eluding his servant, Hidetora flees into the wilderness and Kyoami loses him.

With Hidetora’s location a mystery and his plight now known, Saburo’s army crosses back into the kingdom to find him. Alarmed at what he suspects is treachery by Saburo and by the entry of Lord Ayabe and Lord Fujimaki on Saburo’s side, Jiro hastily mobilizes his army to stop them. Before meeting up with them on the battlefield Lady Kaede tells Jiro to let Saburo take Hidetora and then send assassins to follow them to later wipe Saburo out. When the two forces meet on the field of Hachiman it’s a beautiful site of amazing cinematography, beautiful bright colors of the uniforms and the flags; and of the armies framed against gorgeous epic landscapes.

Sensing a major battle, Saburo’s new patron Fujimaki marches to the border. Ayabe, also shows up with his own army ready for an attack. After Jiro arranges a truce with Saburo to let him take their father, Saburo waits until sunset to head off to find Hidetora. While waiting in position Kurogane informs Jiro, “On that ridge we have Ayabe. On the other Fujimaki await’s his chance. This is the moment of truth. We must stand firm and give them no excuse to attack.” Against the advice of Kurogane, Jiro still orders an attack after Saburo and his men leave the next morning.

Jiro believes his army can destroy Ayabe and Fujimkai’s clan and that the Ichimonji will then take over their land. Kurogane says, “Brave words, but brave words don’t win. What spell did Lady Kaede put on you?” Jiro issues the attack but because of thinking impulsively out of greed for power and land; Jiro’s army is eventually overpowered and driven back towards their castle.

Near the climax of the film, when Jiro’s men flee back to the castle, Kurogane is delivered a package of Lady Sué’s head. Kurogane angrily goes up to confront Lady Kaede when he finds out she sent assassins out secretly to catch Lady Sué and claim her. Before confronting her Jiro tries to stop him but he doesn’t let him get in the way, knowing she poisoned his mind.

In one of the best scenes of the film when he finally confronts her of her treachery, she calmly is sitting down while their castle is slowly being under attack by Lord Fujimaki and Lord Ayabe. Lady Kaede finally reveals her true intentions by saying, “my sole desire was to avenge my family by watching the house of Ichimonji fall and seeing this castle burn.” Kurogane pulls out his sword and in one of the greatest death scenes in film-history makes a large swipe with his sword decapitating her off-screen; as the audience sees an exaggerated amount of blood spray out and onto the wall. He then tells Jiro that it’s over, they lost and they all must prepare to die.

In the tragic end of the film, Saburo finally finds Hidetora. The two are reunited together and Hidetora is at first ashamed and cannot look at his son. In time he comes back to his senses and they ride off together to head to Lord Fujimaki’s castle “I have so much to tell you Saburo. You and I will talk quietly alone, just father and son,” says Hidetora and they both smile and laugh riding along on horseback together.

Suddenly there is a distant gunshot sound and Saburo slumps over and falls off his horse killed by a gunshot wound from one of Jiro’s sent assassins. Tango, Kyoami and Hidetora are speechless as Hidetora looks over at his son’s body. “Saburo”, he says. “You can’t die. I have things to tell you. Forgiveness to beg. Are you really gone forever?” Suddenly while yelling out mourning his dead son’s name, Hidetora has a heart attack and dies on top of his son.

After Saburo and Hidetora’s sudden death; Kyoami starts angrily yelling out at the gods blaming them for what had happened. Tango tells him to stop and says to him what I believe the theme of the film is all about. “Do not curse the Gods! It is they who weep. In every age they’ve watched us tread the pain of evil unable to live without killing each other. They can’t save us…from ourselves.”

The last shot of the film shows Lady Sué’s blind brother Tsurumaru standing at the edge of a cliff, with a blood-red sun set behind him.

ANALYZE

Ran is the late masterpiece and testament of a great director contemplating his own twilight—and the world’s as well. It’s a tragedy fed by Shakespeare, Noh, and the samurai epic, full of metaphors and grand themes, a film that shows human brutality, warfare, and suffering as if from the eye of a dispassionate God, seated far above the world’s terror. In King Lear, we hear that spine-chilling speech, “As flies to wanton boys, so we are to the gods. They kill us for their sport.” But in Ran, it is the humans who kill, wantonly and bloodily, before a God who never interferes, freezingly sad and silent.

Three decades separate Ran from Akira Kurosawa’s other great epic, Seven Samurai (1954), and though each is a grand, visually overwhelming saga of warfare, they’re quite different in style and effect. Seven Samurai is robust, earthy, full of lusty humor, excitement, and emotion—a film by a director in his prime. Ran, made when Kurosawa was seventy-five, is coldly beautiful, bleak, horrifying, and remote, with an Olympian view that holds little sympathy for most of the main characters.

Three decades separate Ran from Akira Kurosawa’s other great epic, Seven Samurai (1954), and though each is a grand, visually overwhelming saga of warfare, they’re quite different in style and effect. Seven Samurai is robust, earthy, full of lusty humor, excitement, and emotion—a film by a director in his prime. Ran, made when Kurosawa was seventy-five, is coldly beautiful, bleak, horrifying, and remote, with an Olympian view that holds little sympathy for most of the main characters.

Where Kurosawa loves the seven samurai led by the wise old Kambei (Takashi Shimura), glorying in their raffish camaraderie and rough-hewn courage, he is unsparing toward Ran’s self-destroying old emperor, Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai), whose ceding of his empire to his sons, Taro (Akira Terao), Jiro (Jinpachi Nezu), and Saburo (Daisuke Ryu), is followed by an avalanche of betrayal and bloodshed. He is clearly contemptuous of Taro and Jiro, and unfazed by the sheer evil of Lady Kaede, the fiendish seductress who incites the war and plunges them all into hell.

As Kurosawa grew older—and especially during the years after 1964’s Red Beard, when his films were more infrequent and his career more difficult—the darkness that had always lain under his work, from Drunken Angel (1948), Stray Dog (1949), and Rashomon (1950) onward, began to grow more apparent. That pessimistic view of human nature and justice, which he shared with the great Russian novelists—and which is softened, in one way or another, in films like Rashomon, Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai—began, in some cases, to swallow up his fictional world. Almost like the darkly comic, cynical Yojimbo (1961), Ran initially shows a war in which both sides, Hidetora’s and his older sons’, are corrupt. If, by the end, we tend to root for Hidetora’s youngest son, Saburo, the true child who tries to rescue his father (Kurosawa’s equivalent for Shakespeare’s faithful Cordelia), it’s not with the intense empathy with which we cheer on Kambei’s samurai.

Instead, Ran’s tide of events is as pitiless toward Saburo as it is toward everyone else, the wicked—Kaede, Taro, Jiro—as well as the good: Jiro’s Buddhist wife, Lady Sue (Yoshiko Miyazaki); the epicene fool, Kyoami, a girlish jester (played by the drag entertainer Peter, in a striking departure from Kurosawa’s usual machismo) who goads and binds himself to his master, Hidetora; Sue’s blind flutist brother, Tsurumaru (Takeshi Nomura), who, in the film’s terrifying last image, is seen teetering on the edge of a cliff, and an abyss, a bloodred sunset flaming behind him.

That resolution has a contemporary edge. The secret subject of Ran—as Kurosawa explained to me in a 1985 interview—is the threat of nuclear apocalypse. The film is saturated with the anxiety of the post-Hiroshima age. But, like Ingmar Bergman’s contemporaneous Fanny and Alexander (1983), the film, set in the past, suggesting the future, also takes the form of a personal testament and mass reunion. For Ran, Kurosawa, as usual, brought back actors (Nakadai, Ryu) with whom he had previously worked. He also assembled a great company of his behind-the-screen collaborators, including scriptwriters Hideo Oguni and Masato Ide; costume designer Emi Wada; art directors Yoshiro and Shinobu Muraki; and his three cinematographers, Takao Saito, Masaharu Ueda, and Asakazu Nakai (Seven Samurai), shooting his last film for Kurosawa.

Most evocatively, the second unit and action direction is again by his longtime friend Ishiro Honda (here described as “associate director”). Honda is most famous as the director of that cult A-bomb parable and sci-fi classic Godzilla, and various monster-movie follow-ups, and together, he and Kurosawa create a world plunged into endless war, shrouded with omnipresent menace and threat.

Ran is a film built on metaphors and grand statements, one that intentionally makes us think before we feel. Kurosawa avoids Shakespeare’s sense of tragic catharsis, and also the fervent emotionality of his own great work of the fifties and sixties. Following Red Beard, he worked more seldom (only about once every five years for a while), in a way, making each new film as if it were his last—as if in Dodes’ka–den (1970), Dersu Uzala (1975), Kagemusha (1980), Dreams (1990), Rhapsody in August (1991), and Madadayo (1993), as well as Ran, he felt he had to cram in all his philosophy and worldview. His art was more careful and willed. His new use of color photography in these late films made them seem almost inevitably more self-consciously picturesque, somewhat less spontaneous and real than a Rashomon or a Seven Samurai. In this period, Kurosawa often painstakingly prepared his visuals with numerous, very beautiful paintings (many of which were exhibited posthumously at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival). His filmmaking technique began to seem more painterly, more classical, and even sober. But if he no longer sought infallibly to rouse and entertain us in the way of his fifties films, he still aimed to strike to the core of existence and the world’s greatest fear.

Nowhere is this change more obvious than in the way that Kurosawa—perhaps the most influential action director of the twentieth century—edits and stages (with Honda) Ran’s fights, murders, and battles. They craft an action movie in which most of the usual exhilaration of screen battle has been deliberately drained away, in which the fiery charge we get from a Seven Samurai, a Hidden Fortress (1958), or a Yojimbo never appears. The battles are often shown from a vast distance, whereas in the fifties films, we are in the middle of the action and the heart of the violence. His signature had been the use of simultaneous three-camera setups and furious editing; in Ran, he shows everything mostly from a single angle, often in continuous takes, with the editing so discreet and inevitable that we barely notice it—save for such poetic devices as the first great battle scene at Saburo’s castle, shown in ritualistic tableaux that eliminate spontaneity and drenched in Toru Takemitsu’s dirgelike, Mahleresque score.

Hidetora is played by Nakadai, the handsome Japanese superstar who first appeared for Kurosawa in a fleeting bit part, as a passing young samurai, in Seven Samurai, and later played the sexy, psychopathic gangster Unasuke in Yojimbo. Nakadai, who also appeared in Kagemusha (where he replaced the original star, the recalcitrant Shintaro “Zatoichi” Katsu), never seized the center of Kurosawa’s world as did Takashi Shimura, with his pure humanity, and the swaggering Toshiro Mifune. But, in a way, his greater fragility and good looks (even tortured into Hidetora’s Noh mask of a face) fit the sense of tenuousness and impermanence that the film everywhere projects. When Nakadai’s Hidetora descends into madness, we may not feel for him as much as we would for the fiercer, more human Mifune in a similar role; Mifune, the great beast, might have ravaged our hearts. But the more exquisite-looking Nakadai, balancing himself between real emotion and stylized, Nohlike gesture, makes us see something crucial: the inevitability of Hidetora’s fate and of the decline of the world he created and that will destroy him.

The themes of Ran are the evil of humanity, the deadly heritage of warfare, and madness. But in showing all this horror, Kurosawa leaves us one great consolation: the beauty of the art with which he reveals it all. The stylization in Ran is not completely original. Besides Shakespeare and Noh, we can see its antecedents in the films of Kenji Mizoguchi, Teinosuke Kinugasa, and other masters from the great thirties-to-fifties era of the Japanese film epic. Where the young Kurosawa had deliberately disrupted the elegant forms of the films from that period, injecting more spontaneity and danger, here he engages with that tradition more subtly, using those films’ overwhelming sense of ritual and the past to create a stabbing feeling of inevitability and fate. Finally, when we see Hidetora and his sons trapped in the poetic frames and staging of Ran, we’re watching a theatricality heightened past grand opera to a point near vertigo and frenzy.

And we’re watching, in the hands of a master (a sensei), a great metaphor of the apocalypse, a world in flames whose chaos is made strangely beautiful.

-Michael Wilmington

Akira Kurosawa’s Ran is an amazing epic story presented on a large epic scale, but it’s also a very small personal story about a man whose sins of his past drive him mad. He was a man who fought wars and committed atrocities all of his life and now at his old age believes he can bring peace to his children before he goes; which instead brings even greater turmoil. Kurosawa is now considered one of the greatest directors in the world, but for several years he didn’t have the respect he deserved. His masterpieces spawned several remakes in the US and even influenced such filmmakers as George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. After creating films like The Seven Samurai, Rashomon, Ikiru, Yojimbo, The Hidden Fortress, High and Low, Throne of Blood and Red Beard, the people in his country were still very hard on Kurosawa.

He was considered as “too Western” and old-fashioned in Japan and struggled to get funding for several of his films. Ran was the final film of Kurosawa’s “third period” during 1965 to 1985 at a time where he had difficulty securing support for his pictures, and was frequently forced to seek foreign financial backing. After directing Red Beard Kurosawa was looked at by Japanese audiences as too old-fashioned and did not work again for almost five years. In 1975 Kurosawa eventually fled to Russia and found Russian financing for his masterpiece Dersu Uzala which had him won the Oscar for Best Foreign language film but it was a failure at the box office. While he had directed over twenty films in the first two decades of his career, Kurosawa directed just four in the last two decades of his life.

When he finally had the funding for his swan song Ran, most of its story was taken from William Shakespeare’s King Lear and when watching it you can see many comparisons. They both depict an aging warlord who decides to divide up his kingdom among his offspring. Hidetora has three sons which correspond to Lear’s daughters Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. In both, the warlord foolishly banishes anyone who disagrees with him as a matter of pride, in Lear it is the Earl of Kent and Cordelia; in Ran it is Tango and Saburo. The conflict in both is that two of the lord’s children ultimately turn against him, while the third supports him, though Hidetora’s sons are far more ruthless than Goneril and Regan. Both King Lear and Ran end with the death of the entire family, including the lord. However, there are some crucial differences between the two. King Lear is a play about undeserved suffering, and Lear himself is at worst a fool.

Hidetora, by contrast, has been a cruel warrior for most of his life and he was a man who ruthlessly murdered men, women, and children to achieve his goals. In the film, Lady Kaede, Lady Sué, and Tsurumaru were all victims of Hidetora and of his horrible acts. Where in King Lear the character of Gloucester had his eyes gouged out by Lear’s enemies, in Ran it was Hidetora himself who gave the order to do the same to Tsurumaru. A reviewer notes that Kurosawa had expanded the role of the Fool into a major character which was Kyoami, played by a transvestite pop star, Peter; and that Lady Kaede was the equivalent of Shakespeare’s Goneril but with a more complex and important character. Critic Stanley Kauffmann said that the main difference between Ran and King Lear are the wars between the sons. “The change is from the spiritual to the physical. Lear was personal, but Ran is gigantically catastrophic.”

The battle scenes in this film are extraordinary and have some of the most beautifully shot battle scenes in all of film history. The shots Kurosawa uses look much more fantastical then realistic and perceive to be more of an abstract classic painting then his black and white samurai films of the 1950’s. Kurosawa would often shoot a scene with three cameras simultaneously, each using different lenses and angles. The techniques and style that Kurosawa used when filming Ran’s action scenes were surprisingly different from the way he shot his actions scenes in the 1950’s. For instance, in Ran many long-shots were employed throughout the film and very few close-ups which is unlike films like Yojimbo, Seven Samurai and The Hidden Fortress. His earlier films from the 1950’s contained more distinct close-ups which made an audience feel as if they were personally inside the action. On several occasions he also used static cameras in Ran and suddenly brought the action into the frame, unlike his older films where Kurosawa used the camera to directly track the action.

Ran was also one of his few color films that Kurosawa had made and like other great directors; he used the color and hues with such sophistication and with exquisite artistry. Eighty percent of the film was shot in exteriors and the summer scenes were mostly lush greens and cool blues. Even though the story is one of Kurosawa’s darkest films story wise, it never is shot dark. It’s always shot with bright warm colors and there is hardly any scenes of shadows or darkness whatsoever; which is a great contrast to the bleak coldness of the story. What makes Ran so extraordinary isn’t just the amazing battle scenes, the epic Shakespearean story, and the beautiful, lush colors and brilliant cinematography. It’s the classic larger than life characters that bring so much personality to the story.

Lord Hidetora seems to be a man who has lived a evil life and achieved the power and respect throughout the years through murder and bloodshed. Now in his later years he feels great shame for the horrible atrocities he had committed and believes by giving over his land to his sons; they can live peacefully and prosperity; which of course does not happen. I feel some sympathy for Hidetora and at the same time I don’t. We never see the horrible atrocities and barbaric acts that he had committed in his youth, even though we hear the horrific stories from some of his victims like Lady Sué, Tsurumaru and Lady Kaede, we never are shown them. In many ways you can think about the story of Ran as a barbaric warlord who built an empire by committing wicked deeds and is finally paying for the sins that he has committed throughout most of his younger life.

I loved the character of Kyoami “the fool” and I loved the quirkiness he brought to the story. He in many ways is a tragic character who never gotten taken seriously and has always been an unfortunate slave to his master Hidetora. When Hidetora goes mad, this is finally his chance to have his master now play the role of the ‘fool’ and be the one who is laughed and mocked at; like the sequence when Kyoami makes Hidetora a straw hat and places it on his master’s head. And yet at the same time there is a sweetness to his character and a love that he holds for his master. I loved Tango and Kurogane who were loyal followers of their masters and even though Kurogane didn’t mind killing Taro; he had his own ethics and a moral stance on killing and when it felt morally wrong to kill Lady Sué, he risked his position to help get her to safety. (Unfortunately it doesn’t work.)

Every great epic needs a great villain and Lady Kaede is one of the most wicked female characters in all of film history. Her painted eyebrows perched high on her forehead in perpetual disapproval, could herself be inspired by Lady Macbeth, as she is a woman bend on hate, bitterness, contempt, to seek out and destroy the family that murdered her own. She is one of the most frightening characters in the cinema and what makes her so scary is that she is smart, deceptive, cunning and highly sexual. She is the woman of every man’s nightmares, always plotting, manipulating and scheming, always one step ahead of everyone else. Having watched Ran several times; I always look at Lady Kaede less and less of a villain each time.

Believe me, I always am looking forward to her classic demise at the end of the film by Lord Kurogane, but her revenge on taking down the Ichimonji clan is quite understandable. Her family was brutally murdered, and if the film showed the gruesome details of her families death; maybe audiences would sympathise with her a little. I am reminded of Frances Ford Coppola’s The Godfather and how Coppola brilliantly has the audience sympathise for people who do evil things; because the violent world is looked at from the inside, not on the outside through the eyes of its victims. Lady Kaede’s contempt and hate for revenge is an fascinating contrast to Lady Sué, who learned to forgive and love her enemies. They were both victims of the same horrible childhoods and so it is ironic and quite tragic that Lady Kaede is the one who orders Lady Sué’s beheading.

Ran was Kurosawa’s last epic film and it was by far his most expensive. At the time, its budget of $12 million made it the most expensive Japanese film in history. Filming of Ran started in 1983. The 1,400 uniforms and suits of armor used for the extras were designed by costume designer Emi Wada and Kurosawa, and were hand-made by master tailors for over more than two years; and the film also used over 200 horses for the battle scenes. Kurosawa loved filming in lush and expansive locations, and most of Ran was shot amidst the mountains and plains of Mount Aso, Japan’s largest active volcano. Kurosawa was also granted permission to shoot at two of the country’s most famous landmarks, the ancient castles at Kumamoto and Himeji. For the castle of Lady Sué’s family, he used the ruins of the Azusa castle. Hidetora’s third castle, which was burned to the ground, was actually a real building which Kurosawa built on the slopes of Mount Fuji. No miniatures were used for that segment, and Tatsuya Nakadai had to do the scene where Hidetora flees from the castle in one take. Legendary critic Roger Ebert agrees, arguing that Ran “may be as much about Kurosawa’s life as Shakespeare’s play.” When Ran was released Roger Ebert awarded the film four out of four stars, writing, Ran is a great, glorious achievement. Kurosawa often must have associated himself with the old lord as he tried to put this film together, but in the end he has triumphed, and the image I have of him, at 75, is of three arrows bundled together.” As Kurosawa grew older, the darkness that was in his earlier work became more apparent. He started showing that pessimistic view of human nature in which was softened in Ikiru and The Seven Samurai. It didn’t matter if you were good or bad whether it was Hidetora, Saburo, Jiro, Taro, Lady Kaede, Lady Sué and Kurogane; everyone sadly perishes at the end of the film besides for Tango and Kyoami. Greed, power, human destruction, past sins and revenge were the many bleak themes in this film which portrays the worst of mankind. After Saburo and Hidetora’s sudden death; Kyoami starts angrily yelling out at the gods blaming them for what had happened. Tango tells him to stop and says to him what I believe the theme of the film is all about. “Do not curse the Gods! It is they who weep. In every age they’ve watched us tread the pain of evil unable to live without killing each other. They can’t save us…from ourselves.” Maybe that’s why the last shot of the film shows Lady Sué’s blind brother Tsurumaru standing at the edge of a cliff. He is a living scar on the evil’s and violence of man, and the sins that we commit to others, as you see a blood-red sun set behind him.

Ran was Kurosawa’s last epic film and it was by far his most expensive. At the time, its budget of $12 million made it the most expensive Japanese film in history. Filming of Ran started in 1983. The 1,400 uniforms and suits of armor used for the extras were designed by costume designer Emi Wada and Kurosawa, and were hand-made by master tailors for over more than two years; and the film also used over 200 horses for the battle scenes. Kurosawa loved filming in lush and expansive locations, and most of Ran was shot amidst the mountains and plains of Mount Aso, Japan’s largest active volcano. Kurosawa was also granted permission to shoot at two of the country’s most famous landmarks, the ancient castles at Kumamoto and Himeji. For the castle of Lady Sué’s family, he used the ruins of the Azusa castle. Hidetora’s third castle, which was burned to the ground, was actually a real building which Kurosawa built on the slopes of Mount Fuji. No miniatures were used for that segment, and Tatsuya Nakadai had to do the scene where Hidetora flees from the castle in one take. Legendary critic Roger Ebert agrees, arguing that Ran “may be as much about Kurosawa’s life as Shakespeare’s play.” When Ran was released Roger Ebert awarded the film four out of four stars, writing, Ran is a great, glorious achievement. Kurosawa often must have associated himself with the old lord as he tried to put this film together, but in the end he has triumphed, and the image I have of him, at 75, is of three arrows bundled together.” As Kurosawa grew older, the darkness that was in his earlier work became more apparent. He started showing that pessimistic view of human nature in which was softened in Ikiru and The Seven Samurai. It didn’t matter if you were good or bad whether it was Hidetora, Saburo, Jiro, Taro, Lady Kaede, Lady Sué and Kurogane; everyone sadly perishes at the end of the film besides for Tango and Kyoami. Greed, power, human destruction, past sins and revenge were the many bleak themes in this film which portrays the worst of mankind. After Saburo and Hidetora’s sudden death; Kyoami starts angrily yelling out at the gods blaming them for what had happened. Tango tells him to stop and says to him what I believe the theme of the film is all about. “Do not curse the Gods! It is they who weep. In every age they’ve watched us tread the pain of evil unable to live without killing each other. They can’t save us…from ourselves.” Maybe that’s why the last shot of the film shows Lady Sué’s blind brother Tsurumaru standing at the edge of a cliff. He is a living scar on the evil’s and violence of man, and the sins that we commit to others, as you see a blood-red sun set behind him.