Modern Times (1936)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Modern Times Charlie Chaplin” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]To make a silent film in 1931 with City Lights four years after the first sound film The Jazz Singer, was a challenge. To make another in 1936 with Modern Times nearly a decade after audiences were now used to sound films, appeared downright perverse. Now audiences were used to the rapid dialog sound comedies of the Marx Brothers and W. C. Fields and were no longer interested in silents. Charlie Chaplin’s refusal to get involved in sound was stretching the limits of fan’s dedications to him and of his character the Little Tramp. Modern Times didn’t do so good at the box office, yet it is now considered his greatest achievement, even though at the time it was considered a huge risk for Chaplin and the future of his career. I believe Charlie Chaplin to be the greatest comedian since the invention of the camera and he joins the ranks of other legendary comedians like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, The Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields and even recent comedians like Peter Sellers, Gene Wilder and Bill Murray. Chaplin once told fellow filmmaker Jean Cocteau “that a film was like a tree: when shaken, it shed everything loose and unnecessary, leaving only it’s essential form.” Modern Times is one of his funniest films that explores the political fears of the common man vs the machine. This was Chaplin’s first overtly political-themed film, and its unflattering portrayal of industrial society and the mechanization world crushing the everyday man generated controversy in some quarters upon its initial release. The opening shot of Modern Times sums up exactly what Chaplin is trying to say to his audience, as it shows a herd of sheep and the very next sequence projects a crowd of men walking into a factory; symbolizing on how human beings have become mindless caddle. It then introduces the Tramp as a factory worker employed on an assembly line, as he struggles to survive in the modern, industrialized world. The subtle use of sounds in the factory sequence is quite extraordinary, as audiences hear the sounds of beeps, buttons, wheels and cranks that are being pulled, pushed and spinned. [fsbProduct product_id=’796′ size=’200′ align=’right’]One of the funniest scenes in the film is where the Tramp is subjected to such indignities as being force-fed by a “modern” feeding machine that eventually goes haywire. Modern Times has probably some of the funniest comedic bits in all of Chaplin’s films, as they include such moments as Chaplin behind bars (he probably gets arrested three different moments throughout the film) accidentally ingesting smuggled cocaine originally mistaking it for salt. Then there is the toy department sequence where the Little Tramp decides to roller-skate blindfolded not knowing the floor is under construction and there is a large drop. And finally there is his job as an efficient waiter, though he finds it difficult to tell the difference between the “in” and “out” doors to the kitchen which causes several accidents and spills. Even though sound was already a major part of the cinema in the year 1936, Chaplin insisted The Tramp would never speak because it would destroy the magic of his character. Modern Times was the very last silent film Chaplin would make and the last time he would use the character of the Little Tramp. Near the end of the film Chaplin does have the Tramp speak through song, even though we don’t really understand what he is saying, but I guess Chaplin thought if Garbo finally spoke, why not have the Little Tramp do so too.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Modern Times Charlie Chaplin” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]To make a silent film in 1931 with City Lights four years after the first sound film The Jazz Singer, was a challenge. To make another in 1936 with Modern Times nearly a decade after audiences were now used to sound films, appeared downright perverse. Now audiences were used to the rapid dialog sound comedies of the Marx Brothers and W. C. Fields and were no longer interested in silents. Charlie Chaplin’s refusal to get involved in sound was stretching the limits of fan’s dedications to him and of his character the Little Tramp. Modern Times didn’t do so good at the box office, yet it is now considered his greatest achievement, even though at the time it was considered a huge risk for Chaplin and the future of his career. I believe Charlie Chaplin to be the greatest comedian since the invention of the camera and he joins the ranks of other legendary comedians like Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, The Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields and even recent comedians like Peter Sellers, Gene Wilder and Bill Murray. Chaplin once told fellow filmmaker Jean Cocteau “that a film was like a tree: when shaken, it shed everything loose and unnecessary, leaving only it’s essential form.” Modern Times is one of his funniest films that explores the political fears of the common man vs the machine. This was Chaplin’s first overtly political-themed film, and its unflattering portrayal of industrial society and the mechanization world crushing the everyday man generated controversy in some quarters upon its initial release. The opening shot of Modern Times sums up exactly what Chaplin is trying to say to his audience, as it shows a herd of sheep and the very next sequence projects a crowd of men walking into a factory; symbolizing on how human beings have become mindless caddle. It then introduces the Tramp as a factory worker employed on an assembly line, as he struggles to survive in the modern, industrialized world. The subtle use of sounds in the factory sequence is quite extraordinary, as audiences hear the sounds of beeps, buttons, wheels and cranks that are being pulled, pushed and spinned. [fsbProduct product_id=’796′ size=’200′ align=’right’]One of the funniest scenes in the film is where the Tramp is subjected to such indignities as being force-fed by a “modern” feeding machine that eventually goes haywire. Modern Times has probably some of the funniest comedic bits in all of Chaplin’s films, as they include such moments as Chaplin behind bars (he probably gets arrested three different moments throughout the film) accidentally ingesting smuggled cocaine originally mistaking it for salt. Then there is the toy department sequence where the Little Tramp decides to roller-skate blindfolded not knowing the floor is under construction and there is a large drop. And finally there is his job as an efficient waiter, though he finds it difficult to tell the difference between the “in” and “out” doors to the kitchen which causes several accidents and spills. Even though sound was already a major part of the cinema in the year 1936, Chaplin insisted The Tramp would never speak because it would destroy the magic of his character. Modern Times was the very last silent film Chaplin would make and the last time he would use the character of the Little Tramp. Near the end of the film Chaplin does have the Tramp speak through song, even though we don’t really understand what he is saying, but I guess Chaplin thought if Garbo finally spoke, why not have the Little Tramp do so too.

PLOT/NOTES

The story of Modern Times is technically made up of 4 parts: The Shop, The Jail, The Watchman and The waiter. The opening shot shows a group of sheep running in a herd and the very next shot shows a crowd of men walking into a factory which is symbolism of human being mindless caddle ordered to do a job and leave. It then introduces the Tramp as a factory worker employed on an assembly line making it hard for him to keep up with the fast paced work.

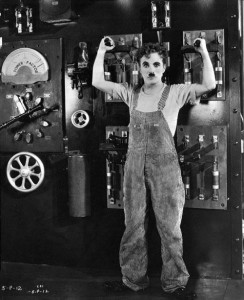

This beginning shot of the film with the Factory portrays the modern world of technology and the slavery like work of it’s workers. The Tramp can’t even use the bathroom to have a short smoke break without his boss watching him from a large TV screen ordering him to get back to work.

One of the funniest scenes in all of film is where the Tramp is subjected to such indignities as being force-fed by a “modern” feeding machine that eventually goes haywire. This scene cannot be described in words and instead must only be scene because of its comedic brilliance. The subtle use of sounds in the scenes with the factory are brilliantly done with sounds of beeps, buttons, wheels and cranks that are being pulled and pushed. The only real speaking you hear is from the boss of the company giving out orders to his co-workers from a large TV screen.

A lot of these scenes of machinery and technology brings to mind the humor and style of Jacques Tati’s work, especially Playtime. Eventually because the Tramp has to screw nuts at an ever-increasing rate onto pieces of machinery, he eventually suffers a mental breakdown that causes him to run amok, throwing the factory into chaos, even continuing to repeat the movements of tightening phantom screws which he attempts on a woman’s behind believing the buttons on her dress are screws. There’s a really neat shot of him actually going inside one of the factory machines and you watch as his body is being carried through all the large gears and eventually going backwards to be pulled back out.

The Tramp is sent to a hospital for having a severe breakdown and following his recovery, the now unemployed Tramp is mistakenly arrested as an instigator in a Communist demonstration. He gets arrested and thrown in jail and accidentally ingests smuggled cocaine, mistaking it for salt. The reference to drugs in this sequence is somewhat daring for the time (since the production code, established in 1930, forbade the depiction of illegal drug use in films.) In his subsequent delirious state he stumbles upon a jailbreak and knocks out the convicts and is hailed a hero and is released.

Outside the jail, he discovers life is harsh, and he gets a new construction job accidentally pulling out a block of wood that was holding a large boat in place which now releases it out into the ocean. He eventually loses that job because of his clumsiness and decides he would rather be in jail because of how hard it is to survive on the outside.

He runs into an orphan and gamine girl, played by Paulette Goddard, who is fleeing the police after stealing a loaf of bread. She herself is trying to support her father and sisters who are also struggling with poverty. To save the girl, and get himself arrested and back to jail the Tramp tells police that he is the thief and ought to be arrested but a witness reveals his deception and he is freed. To get himself arrested again, he decides to go in a cafeteria and eat an enormous amount of food without paying, which eventually does work and he is arrested and put in the back of a paddy wagon.

He meets up with the gamine girl in the paddy wagon, which suddenly crashes, and the girl convinces the reluctant Tramp to escape with her. Dreaming of a better life together, he gets a job as a night watchman at a department store, sneaks the gamine into the store and they decide to go into the toy department and roller-skate. A great scene shows the Tramp deciding to roller-skate blindfolded not knowing the floor is under construction and there is a large drop. Of course before falling after a few close calls the gamine grabs him in time.

Later that evening burglars break in and guns go off which poke holes in several barrels of alcohol which accidentally gets the Tramp drunk. One of the burglars recognizes the Tramp from the last factory job that he worked for and he tells the Tramp that their stealing food to help feed their families. Waking up the next morning in a pile of clothes in the store probably with a hangover, the Tramp is arrested once more. After getting out ten days later, the gamine takes him to a new home—a run-down shack that’s on the verge of collapsing. She admits “it isn’t Buckingham Palace” but will do.

The next morning, the Tramp reads about a new factory job in the paper and quickly runs out and lands a job there. His first day there he gets his boss trapped in the gears of a machine, and when lunch begins the Tramp manages to feed him while still stuck by using a chicken as a funnel to pour hot coffee in his bosses mouth. After eventually getting him out the workers all decide to go on strike.

Accidentally paddling a brick into a policeman, the Tramp is arrested once again. (I think he gets arrested and released three or four times in the film!) Two weeks later, he is released and the gamine is outside waiting for him. She tells him she landed a job as a café dancer and tries to get him a job there as a singer.

His first night at his new job, he becomes an efficient waiter though he finds it difficult to tell the difference between the “in” and “out” doors to the kitchen which causes several accidents and spills and also struggles to successfully deliver a roast duck to a table through a busy dance floor. During his floor show where he is ordered by his boss to sing, he loses a cuff that bears the lyrics of his song, (which is a song by Léo Daniderff’ titled Je cherche après Titine) but he rescues his act by improvising the story using an amalgam of word play, words in (or made up words or parts from) multiple languages and mock sentence structure while pantomiming which proves a hit for the audience.

When police arrive to arrest the gamine for her earlier escape, the Tramp and her both escape from the police. This classic scene of finally hearing the Tramp speak is one of the most memorable scenes of the film. While trying to understand the song which appear to contain words from French and Italian, it seems like a lot of suggested sexual lyrics and Chaplin’s version of this song is most commonly called ‘The Nonsense Song’. I believe this scene was a sort of farewell to the silent era and to the character of The Little Tramp which made Chaplin the most famous man in the world.

At the end of the film when The Tramp and the gamine are both out of a job and find themselves on the street again the gamine says, “What’s the point of trying,”and starts crying. The Tramp tells her to “Buck up. Never say die. We’ll get along.” It’s these touching uplifting moments that make Charlie Chaplin and the character of The Little Tramp always live on in audiences’ heart’s as we see them walking down a road at dawn, towards an uncertain but hopeful future.

ANALYZE

To make a silent film in 1931, four years after The Jazz Singer, was to buck the trend in a film industry rapidly divesting itself of silence. To make another in 1936, nearly a decade after the advent of sound, appeared downright perverse. Charlie Chaplin had once been the paramount icon of modernity, rushing headlong across the screen in a dazzling imitation of the speed and grace of contemporary life. In clinging stubbornly to silence with City Lights, and then (mostly) with Modern Times, however, he was risking seeming, of all things, passé. For audiences accustomed to the rapid-fire patter of the Marx Brothers, W. C. Fields, and Mae West, Chaplin’s refusal was stretching the limits of their dedication to the Little Tramp—Modern Times, especially, suffered at the box office. And yet, when accounts are tallied of Chaplin’s greatest works—the foremost films of the foremost performer in the history of American film—these two era-straddling anomalies are often at the top.

Chaplin once told fellow filmmaker Jean Cocteau that a film was like a tree: when shaken, it shed everything loose and unnecessary, leaving only its essential form. For the man who had created the most beloved film character of all time, spoken dialogue was merely a decorative leaf distracting attention from the sturdy oak of performance. Twirling his cane, tipping his hat with delightful delicacy to a generation of moviegoers, Chaplin’s Tramp had needed no words to communicate. “For years, I have specialized in one type of comedy—strictly pantomime,” Chaplin observed in 1931, the year of City Lights. “I have measured it, gauged it, studied. I have been able to establish exact principles to govern its reactions on audiences. It has a certain pace and tempo. Dialogue, to my way of thinking, always slows action, because action must wait on words.”

Chaplin was afraid of losing what had made him so remarkable by embracing sound, but he also feared irrelevance. “I was obsessed by a depressing fear of being old-fashioned,” he said of his hiatus from filmmaking after City Lights. But how could he modernize without erasing what was unique about him? This was the problem posed and, for the moment, solved by Modern Times. “I forget the words,” the Tramp pantomimes to his love (played by Paulette Goddard), referring to a song, and what is true of the character was true of the artist as well. For the film is not silent, precisely; it is merely without dialogue, while featuring music, sound effects, and a climactic bit of Chaplin’s own singsong gibberish (about which more shortly). It is a recapitulation of his earlier work, the director taking a triumphant final lap around the style he did so much to invent, before reluctantly turning to the new challenges of sound. In it, the Tramp bows one last time to the audience that has loved him so much, before disappearing forever.

We think of Chaplin as such a product of the twentieth century—its technological prowess, its speed, its ready commodification—that it is easy to forget that the man himself was a child of the nineteenth century, born in London in 1889. Chaplin’s childhood was brief, cut short by the tragedies of losing his father to alcoholism-induced dropsy and his mother to the ravages of mental illness. Charlie spent much of his youth in dreary workhouses, interrupted by brief stints with relatives, before setting out on his own at the age of fourteen.

The young Chaplin wheedled his way into a temporary position with Fred Karno’s vaudeville company in 1908. Karno had hired Chaplin’s half brother and protector Sydney two years earlier but soon discovered that it was undoubtedly Charlie who was the star of the family, as he would be of the company. The Karno players toured incessantly, and on one American jaunt, Chaplin was summoned to an attorney’s office for a meeting. He assumed that he was to receive a bequest from a relative, but what was on offer was far more significant: a contract to join Mack Sennett’s Keystone film company in Los Angeles, at $150 a week.

The young Chaplin wheedled his way into a temporary position with Fred Karno’s vaudeville company in 1908. Karno had hired Chaplin’s half brother and protector Sydney two years earlier but soon discovered that it was undoubtedly Charlie who was the star of the family, as he would be of the company. The Karno players toured incessantly, and on one American jaunt, Chaplin was summoned to an attorney’s office for a meeting. He assumed that he was to receive a bequest from a relative, but what was on offer was far more significant: a contract to join Mack Sennett’s Keystone film company in Los Angeles, at $150 a week.

The elements came together rapidly. The costume—too-large pants, too-small jacket, little hat, and big shoes—was grabbed out of Keystone’s wardrobe closet for an early short. The duck-footed waddle was borrowed from a figure Chaplin remembered from his London childhood. The raucous mayhem was the trademark of Sennett, creator of the Keystone Kops, but the jaunty tone of exuberant politesse—the tipped hat and twirled cane—was Chaplin’s own.

Chaplin’s early years in Hollywood were a remarkable blur of improvisatory brilliance and astounding artistic growth. Sennett was an ideal mentor, but Chaplin rapidly outgrew the roughhousing, looking beyond slapstick to something subtler. Shorts like The Rink (1916), One A.M. (1916), and The Immigrant (1917) are perhaps the finest examples of his virtuosic physical gifts, of the unexpected reversals and inversions at the heart of his humor, and of his deft sentimental touch. The Tramp is heroic, and heroically self-serving, and his manipulations of the physical world are magnificently cunning. The films’ plots are the artificial limits placed on Chaplin’s seemingly limitless ingenuity, the net that turns anarchy into a civilized game of tennis.

Chaplin argued, during his one- and two-reel reign in the 1910s, that comedies, by their nature, should be no longer than they already were—that the requirements of the feature film would inevitably distort the charms of the form. The director had, though, been subtly shifting the concept of what a Tramp short could be; the nakedly emotional Easy Street (1917), for example, was hardly the stuff of Keystone comedy. Restless as he was, Chaplin soon saw that he had conquered the ten-to-twenty-minute format. He could go on indefinitely producing variations on 1916’s The Pawnshop (and there are those who claim, not unreasonably, that that was what he did best), but he preferred the uncertainty of a fresh challenge. The emotional tug of late Chaplin shorts like The Immigrant demanded a broader canvas.

Chaplin’s feature-length films are not merely extensions of his shorts; they are translations of his comic technique into a more flexible, emotive form. The shorts are brilliant, but they primarily document the brilliance of the performer; the features allow Chaplin to vary the emotional palette of his work and to engage his skill as a filmmaker. The shorts had made Chaplin a star, but the features made him an artist. The Tramp is no longer just a miraculously energetic scamp but also a fragile soul wounded by a cruel, uncaring world. Chaplin features like The Kid (1921), The Gold Rush (1925), and City Lights (1931) are hardly less astonishingly amusing than his shorts, but they add a dimension of feeling heretofore lacking in his work. Chaplin was adamant that the Tramp would never speak, and given the indubitable genius of his performances in The Gold Rush and City Lights, one sees his point. Modern Times would be the Tramp’s last run.

In his review of Modern Times for the New Republic, Otis Ferguson argued that the film could best be understood as a return to Chaplin’s roots: “It is a feature picture made up of several one- or two-reel shorts, proposed titles being The Shop, The Jailbird, The Watchman, and The Singing Waiter.” And indeed, the film does divide neatly into four segments, of which the one Ferguson dubbed The Shop—wherein the Tramp is seen working the assembly line until he becomes the assembly line—is easily the most memorable, and remembered. (One could argue that all of Jacques Tati’s work springs from this segment of Modern Times.) The structure of the film, that is, reflects a certain nostalgia for Chaplin’s past glories.

But Modern Times also points to a new phase in Chaplin’s life and thinking, to changes in his outlook, personal as well as aesthetic. The film marks the first time that his private political awakening—his most costly transformation, born of his experiences of the previous decade—appears tangibly on the screen. Later, he would be accused of being a communist, but the film’s political symbols (a humbled worker here, what appears to be a red flag there) are mostly subsumed by the humor. Overall, Chaplin seems to be drawing a connection between his awareness of the Tramp’s obsolescence—and, potentially, his own—and fears about the mechanization of modern life and its potential for crushing the common man, whom the Tramp has come to symbolize. His apprehensions are writ large in Modern Times, transmuted from a lone filmmaker to all of humanity: it is the machine that is mankind’s true opponent, deadening the senses and twisting flesh into steel.

Chaplin is in earnest about his concerns, but he successfully translates them into the stuff of superlative comedy. To see the Tramp strapped into an auto-feeding machine, being shoveled a steady diet of metal nuts, or emerging from a shift on the factory line still adjusting phantom screws (even attempting to tighten the buttons on a woman’s dress), is to witness Chaplin’s alchemical gift for transforming anxiety into humor. The Tramp is menaced by technology, and while Chaplin’s revenge is only partial and symbolic, it is essential nonetheless.

Chaplin pits the Tramp’s superhuman improvisational abilities against a soulless mechanical sphere that, he believes, is the negation of our collective humanity. Witness the brilliant scene where the Tramp must feed lunch to his coworker, stuck inside the gears of an enormous machine. Charlie uses a chicken as a funnel to pour hot coffee into his recumbent friend’s mouth. Chaplin is, in essence, placing his own genius in competition with modernity, asking audiences to root for his inventive brilliance over the unthinking dutifulness of the machine.

In Paulette Goddard, with whom he was romantically linked at the time, Chaplin finds his ideal female lead. Modern Times is not his most romantic work—that title unquestionably belongs to City Lights—but after years of limited female costars, Chaplin finally had one whose zest, charm, and energy approximated his own. Their characters’ romance is a painful one, as all of Chaplin’s screen entanglements are, but he grants Goddard the rare privilege of walking off into the distance with him at the film’s end, two wanderers content with the open road—and each other.

Modern Times is actually, secretly, an origin story for the Tramp, just in time for his farewell. When Charlie is hired as a singing waiter and belts out a charming gibberish song composed of jumbled, faux-Italian syllables—Chaplin’s virgin attempt at producing sound, if not speech, on-screen—we are witnessing the birth of an entertainer. All that has passed is mere prologue. But the singing Tramp would not go on.

After Modern Times, Chaplin grew increasingly serious about politics, specifically the threat of fascism. And with the rise of Adolf Hitler and the onset of World War II, he became more outspoken, addressing a war rally in San Francisco on the urgency of Russian war relief, referring to the crowd as “comrades.” What seemed like innocuous patriotic fervor during the war took on, for some, a disturbing red tinge afterward, and fervent anticommunists sought to tar Chaplin as a Soviet fellow traveler. In 1952, as Charlie, his wife, Oona, and their four children traveled by boat to London for the premiere of Limelight, word came by radio that U.S. attorney general James McGranery had invalidated Chaplin’s reentry permit, calling for the INS to hold hearings on his fitness to reside in the country. McGranery hinted at secret documentation that would reveal much about the actor and director’s “unsavory character.” Chaplin and his family resettled in Switzerland. He would not set foot in the United States for another twenty years—when, more than four decades after the Academy had first presented him with an honorary award, for The Circus (1928), he was summoned back from exile to receive a lifetime achievement Oscar.

Whether because of changing political or aesthetic winds, Chaplin’s films after Modern Times never received the universal acclaim of his earlier work. The Great Dictator (1940), which viciously parodied Hitler, was well-liked though criticized by many for preachiness, and later Chaplin efforts like Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Limelight, and A King in New York (1957)—as bitter as they were sweet—were battered by critics, who found them dogmatic.

The unique triumph of Modern Times is that it maintains the playful aura of the early Tramp and the comedic sophistication of The Gold Rush and City Lights, all while carefully balancing the humor with sentiment, charm with political awareness. It is Chaplin before life, and the world of which he was an ever more careful observer, began to weigh him down. With it, he bid a fond farewell to the silent film, and to the character who had made him the most famous man in the world. For Chaplin, it was the end of an era. But for fans of the greatest talent ever to grace the American screen, that era can be retrieved merely by cuing up Modern Times once more.

-Saul Austerlitz

Charlie Chaplin was born in London in 1889 and his childhood was full of hardship with a father who died of alcoholism and a mother who suffered from severe mental illness. Struggling with poverty, Chaplin was sent to a workhouse at seven years old before he finally set out on his own at the age of fourteen. Chaplin’s struggling childhood prompted biographer David Robinson to describe his eventual trajectory as “the most dramatic of all the rags to riches stories ever told.” Maybe Chaplin’s hard childhood propelled him to develop the character of The Little Tramp whose stories focus on poverty, the harshness and cruelty of the outside world, and the contrasts between the rich and the poor.

Chaplin’s early years in Hollywood were a brilliant mixture of improvisation and artistic growth where he moved beyond the form of slapstick comedy and delved into more subtle like humor. Shorts like The Immigrant in 1917 is the best example of his early artistic talents and that’s where he created The Tramp character wearing a costume with too large-sized pants, a little hat, big floppy shoes and a duck footed waddle which was borrowed from a figure Chaplin remembered from his early childhood in London. The personality of the Tramp, the sweetness, love and romantic characteristics with his tipped hat and cane was created by Chaplin himself.

When Chaplin started doing feature-length films it gave him more room to be flexible and extend his comic talents into something deeper and much more grander. In his feature-length films his Little Tramp became not just energetic amusement but also a fragile soul that is wounded by a harsh uncaring world which was during the time of the Great Depression. Thousands of Americans at that time were homeless and were struggling with unemployment and poverty which was something Chaplin could relate to with his early life. His Tramp character doesn’t make light of these harsh situations but made audiences relate to the Tramp’s suffering and hardships he has to endure, and at the same time made them smile with the Tramp’s innocence and sweetness.

His first real masterpiece The Kid in 1921 wasn’t more amusing than his earlier shorts but it added a dimension of tragedy which was lacking in is earlier work. At the time The Kid was released it became a high point for Chaplin’s career where he afterwards created not only some of the greatest comedies but the greatest films ever made with masterpieces like The Gold Rush in 1925; with the classic scene of the Tramp cooking and eating a shoe with a knife and fork and The Circus in 1928. My personal favorite was City Lights in 1931 which to me says everything about the beauty and art of cinema. Sound was already in films at that time and Chaplin insisted The Tramp would never speak because it would destroy the magic of his character and feared it would alienate his fans in non-English speaking territories.

Modern Times in 1936 was the very last silent film he made and the last time he would use the character of the The Little Tramp. Near the end of the film Chaplin does have the Tramp speak through song, even though we don’t really understand what he is saying. I guess Chaplin thought if Garbo finally spoke, why not have the Little Tramp finally speak as well. Chaplin later made other classics as well even though many agree aren’t considered his best compared to his earlier work. He made the controversial film The Great Dictator in 1940 mocking Adolf Hitler even before Americans went to war with Germany which was a big risk at the time. Later on he made films which were darker and more political in tone with Monsieur Verdoux in 1947 and Limelight in 1952.

Chaplin began preparing the film in 1934 as his first “talkie”, and went as far as writing a dialogue script and experimenting with some sound scenes. However, he soon abandoned these attempts and reverted to a silent format with synchronized sound effects, like the sound of gears and buttons and sounds primarily used for comedic effect; like the scene with his stomach growling sitting next to a wealthy wife of a minister. The dialogue experiments confirmed his long-standing conviction that the universal appeal of the Tramp would be lost if the character ever spoke on-screen. Most of the film was shot at “silent speed”, 18 frames per second, which when projected at “sound speed”, 24 frames per second, makes the slapstick action appear even more frenetic. Available prints of the film now correct this. The filming was long, beginning on October 11, 1934 and ending on August 30, 1935.

Modern Times exhibits notable similarities to a 1931 French film directed by René Clair entitled À nous la liberté especially the assembly line sequence. The German film company Tobis Film sued Chaplin following the film’s release to no avail. They sued again after World War II (which was considered revenge for Chaplin’s later anti-Nazi statements in The Great Dictator.) and eventually settled with Chaplin out of court. À nous la liberté’s director Clair was an outspoken admirer of Chaplin, was flattered by the notion that the film icon might imitate him, and was deeply embarrassed that Tobis Film would sue Chaplin and said was never part of the case. There are a lot of strong themes I noticed when watching this film and a major theme is about the everyday American struggling to support themselves and their family. The gamine girl is a tragic American character like the Tramp and after losing custody of her little sisters after the death of her father she becomes homeless and eventually the Tramp and her find each other. Charlie Chaplin is portraying America as a sad dark time during the Great Depression, where even good people commit crimes because of the need to feed their family. He also shows themes of the everyday man struggling to survive in the modern, industrialized world which is politically symbolic of the fears of the common man vs the machine. This was Chaplin’s first overtly political-themed film, and its unflattering portrayal of industrial society and the mechanization world crushing the everyday man generated controversy in some quarters upon its initial release. Modern Times is considered one of the great silent masterpieces of film and one of the greatest films of all time. I believe Charles Chaplin to be one of the greatest of all directors next to Welles, Bergman, Ford, Fellini, Wilder, Lang, Godard, Hawks and Kubrick. The creation of The Tramp is one of the major icon’s of American culture and Chaplin created a character who was tragic, romantic, innocent, sweet and very, very, funny. At the end of the film when The Tramp and the gamine are both out of a job and find themselves on the street again the gamine says, “What’s the point of trying,”and starts crying. The Tramp tells her to “Buck up. Never say die. We’ll get along.” It’s these touching uplifting moments that make Charlie Chaplin and the character of The Little Tramp always live on in audiences’ heart’s as we see them walking down a road at dawn, towards an uncertain but hopeful future.

Modern Times exhibits notable similarities to a 1931 French film directed by René Clair entitled À nous la liberté especially the assembly line sequence. The German film company Tobis Film sued Chaplin following the film’s release to no avail. They sued again after World War II (which was considered revenge for Chaplin’s later anti-Nazi statements in The Great Dictator.) and eventually settled with Chaplin out of court. À nous la liberté’s director Clair was an outspoken admirer of Chaplin, was flattered by the notion that the film icon might imitate him, and was deeply embarrassed that Tobis Film would sue Chaplin and said was never part of the case. There are a lot of strong themes I noticed when watching this film and a major theme is about the everyday American struggling to support themselves and their family. The gamine girl is a tragic American character like the Tramp and after losing custody of her little sisters after the death of her father she becomes homeless and eventually the Tramp and her find each other. Charlie Chaplin is portraying America as a sad dark time during the Great Depression, where even good people commit crimes because of the need to feed their family. He also shows themes of the everyday man struggling to survive in the modern, industrialized world which is politically symbolic of the fears of the common man vs the machine. This was Chaplin’s first overtly political-themed film, and its unflattering portrayal of industrial society and the mechanization world crushing the everyday man generated controversy in some quarters upon its initial release. Modern Times is considered one of the great silent masterpieces of film and one of the greatest films of all time. I believe Charles Chaplin to be one of the greatest of all directors next to Welles, Bergman, Ford, Fellini, Wilder, Lang, Godard, Hawks and Kubrick. The creation of The Tramp is one of the major icon’s of American culture and Chaplin created a character who was tragic, romantic, innocent, sweet and very, very, funny. At the end of the film when The Tramp and the gamine are both out of a job and find themselves on the street again the gamine says, “What’s the point of trying,”and starts crying. The Tramp tells her to “Buck up. Never say die. We’ll get along.” It’s these touching uplifting moments that make Charlie Chaplin and the character of The Little Tramp always live on in audiences’ heart’s as we see them walking down a road at dawn, towards an uncertain but hopeful future.