Man with the Movie Camera (1929)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Man with a Movie Camera Vertov” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Never had I known that these mechanical noises could be arranged to sound so beautiful. Mr. Dziga Vertov is a musician,” stated Charlie Chaplin after he first witnessed Vertov’s early film Enthusiasm in London. And still Vertov took the language of sound to an even greater level when making his masterpiece Man with the Movie Camera (also called Man with a Movie Camera) which is looked at as one of the most revolutionary silent films ever made. It was said that the average film shot length (ASL) was around 11.2 seconds in the year 1929. When Man with the Movie Camera was released it had an ASL of 2.3 seconds, which is four times faster than most films of that time and the speed of the average action film made today. And so when people first laid there eyes on images and edits that were flying passed them at a speed of 2.3 seconds in the year 1929, it must of stunned them. It horrified the author of the New York Times as he wrote in his review of the film, “The producer, Dziga Vertov, does not take into consideration the fact that the human eye fixes for a certain space of time that which holds the attention.” Most films made during this period were stuck into the tradition of simple stage plays, and Vertov wanted to show the world that the cinema could break free from that tradition and move on a much faster speed. Vertov wanted audiences to undergo a free-association process which processes information as fast as our brain and incorporates it with the cinema along with the speed of a passionate musical composition. [fsbProduct product_id=’1487′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Right in the beginning inter-titles Vertov lets the audience know what kind of film to expect. He informs us the film is an experiment in the cinematic communication of visible events, without the aid of inter-titles, without the aid of a scenario and without the aid of a theater. He states the film is simply a series of images that is creating an absolute language of cinema by separating the language from the theater and literature. Man with the Movie Camera has a basic organizing format and a form of structural layout throughout the film. Vertov would open from dusk and close at dawn, a complete 24 hour single day throughout three cities: Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. It took Vertov nearly a total of four years to film this day with the help of his wife Yelizaveta Svilova who supervised the editing which involved nearly 1,7775 separate shots of film; which is a staggering amount of film to edit provided that most of these shots consisted of nearly set-ups.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Man with a Movie Camera Vertov” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Never had I known that these mechanical noises could be arranged to sound so beautiful. Mr. Dziga Vertov is a musician,” stated Charlie Chaplin after he first witnessed Vertov’s early film Enthusiasm in London. And still Vertov took the language of sound to an even greater level when making his masterpiece Man with the Movie Camera (also called Man with a Movie Camera) which is looked at as one of the most revolutionary silent films ever made. It was said that the average film shot length (ASL) was around 11.2 seconds in the year 1929. When Man with the Movie Camera was released it had an ASL of 2.3 seconds, which is four times faster than most films of that time and the speed of the average action film made today. And so when people first laid there eyes on images and edits that were flying passed them at a speed of 2.3 seconds in the year 1929, it must of stunned them. It horrified the author of the New York Times as he wrote in his review of the film, “The producer, Dziga Vertov, does not take into consideration the fact that the human eye fixes for a certain space of time that which holds the attention.” Most films made during this period were stuck into the tradition of simple stage plays, and Vertov wanted to show the world that the cinema could break free from that tradition and move on a much faster speed. Vertov wanted audiences to undergo a free-association process which processes information as fast as our brain and incorporates it with the cinema along with the speed of a passionate musical composition. [fsbProduct product_id=’1487′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Right in the beginning inter-titles Vertov lets the audience know what kind of film to expect. He informs us the film is an experiment in the cinematic communication of visible events, without the aid of inter-titles, without the aid of a scenario and without the aid of a theater. He states the film is simply a series of images that is creating an absolute language of cinema by separating the language from the theater and literature. Man with the Movie Camera has a basic organizing format and a form of structural layout throughout the film. Vertov would open from dusk and close at dawn, a complete 24 hour single day throughout three cities: Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. It took Vertov nearly a total of four years to film this day with the help of his wife Yelizaveta Svilova who supervised the editing which involved nearly 1,7775 separate shots of film; which is a staggering amount of film to edit provided that most of these shots consisted of nearly set-ups.

PLOT/NOTES

Man With the Movie Camera opens brilliantly in the early hours of dawn, presenting an empty city, an empty cinema, and its empty seats as an orchestra stands at attention. The seats eventually swivel down by themselves, and an audiences rushes in to fill its seats. They begin to look at the blank theater screen and right when the film begins to be presented to them, the orchestra begins to play. The film is about this film being made, as the audience in the cinema (which includes us) watches a man with a movie camera present to us how this film got made. He carries a early hand-cracked camera model including its tripod, which looks slightly similar to the one Buster Keaton uses in The Cameraman. The camera and its tripod seems to be light enough for the man to carry around on his shoulder throughout the busy streets, as the audience watches him take extraordinary photography shots of the movie, whether its on the top of a speeding automobile, hanging in a basket over a magnificent waterfall, or stooping low enough through a claustrophobic coal-mine. This man with the movie camera gives us footage of the movement and function of heavy machinery, trolleys, babies, boats, sports, crowds, buildings, production line workers, children, streets, planes, beaches, crowds, hundreds of individual faces and expressions, and thousands of simple daily routines.

But these shots all have an organizing pattern that goes along beautifully with the rhythm of the boosting Alloy Orchestra (Which is included on the Image DVD, Michael Nyman presents the soundtrack for the Kino version) that Vertov has written, composed and accompanies for us. It’s been said that Vertov worked the structure of the film within a Marxist ideology, as he strove to create a futuristic city that would serve as a form of commentary on the existing Soviet ideals with Russian society. These particular ideals were to awaken Soviet citizens and ultimately bring a form of understanding of truth and action to the people of Russia as Vertov’s ‘kino-eye’ aesthetic is viewed by some historians as early modernism within film, with his portrayal of electrification, industrialization, and the achievements of workers through hard labor. Vertov’s revolutionary avante-garde montage of Constructivist and modern architecture makes The Man With the Movie Camera one of the most fascinating and brilliant films to have ever have come out of the movement of Soviet montage.

SOVIET MONTAGE

Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein wrote Battleship Potemkin originally as a revolutionary propaganda film, but also to test his theories of Soviet Montage. Montage is a synonym for a form of editing which was practiced by Soviet filmmakers Lev Kuleshov, Vesvolod Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein around the 1920s at the Kuleshov school of film-making. Each filmmaker incorporated their own forms and ideologues of Soviet Montage differently into their films under the teachings of Lev Kuleshov, placing these ideas into political concepts. Eisenstein called these different forms ‘Cinema of Attractions’ and experimented with a form of film editing which attempted to produce the greatest emotional response in a viewer by conflicting two different shots side created from juxtaposition. Soviet Montagists took the work of editing away from mere exposition and focused on materialization of ideas, motifs, symbols, metaphors, themes, and concepts through editing.

In formal terms, Soviet Montage’s style of editing offers discontinuity in graphic qualities, violations of the 180 degree rule, and the creation of impossible spatial matches. It is not concerned with the depiction of a comprehensible spatial or temporal continuity as is found in the classical Hollywood continuity system. It draws attention to temporal ellipses because changes between shots are obvious, less fluid, and non-seamless.

Eisenstein describes five methods of montage in his introductory essay ‘Word and Image’. These varieties of montage build one upon the other so the higher forms also include the approaches of the “simpler” varieties. In addition, the “lower” types of montage are limited to the complexity of meaning which they can communicate, and as the montage rises in complexity, so will the meaning it is able to communicate (primal emotions to intellectual ideals). It is easiest to understand these as part of a spectrum where, at one end, the image content matters very little, while at the other it determines everything about the choices and combinations of the edited film.

Eisenstein’s montage theories are based on the idea that montage originates in the “collision” between different shots in an illustration of the idea of thesis and antithesis. This basis allowed him to argue that montage is inherently dialectical, thus it should be considered a demonstration of Marxism and Hegelian philosophy. His collisions of shots were based on conflicts of scale, volume, rhythm, motion (speed, as well as direction of movement within the frame), as well as more conceptual values such as class.

- Metric – where the editing follows a specific number of frames (based purely on the physical nature of time), cutting to the next shot no matter what is happening within the image. This montage is used to elicit the most basal and emotional of reactions in the audience.

- Metric montage example from Eisenstein’s October.

- Rhythmic – includes cutting based on continuity, creating visual continuity from edit to edit.

- Rhythmic montage example from The Good The Bad and the Ugly where the protagonist and the two antagonists face off in a three-way duel

- Another rhythmic montage example from The Battleship Potemkin’s “Odessa steps” sequence.

- Tonal – a tonal montage uses the emotional meaning of the shots—not just manipulating the temporal length of the cuts or its rhythmical characteristics—to elicit a reaction from the audience even more complex than from the metric or rhythmic montage. For example, a sleeping baby would emote calmness and relaxation.

- Tonal example from Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin. This is the clip following the death of the revolutionary sailor Vakulinchuk, a martyr for sailors and workers.

- Overtonal/Associational – the overtonal montage is the cumulation of metric, rhythmic, and tonal montage to synthesize its effect on the audience for an even more abstract and complicated effect.

- Overtonal example from Pudovkin’s Mother. In this clip, the men are workers walking towards a confrontation at their factory, and later in the movie, the protagonist uses ice as a means of escape.

- Intellectual – uses shots which, combined, elicit an intellectual meaning.

- Intellectual montage examples from Eisenstein’s October and Strike. In Strike, a shot of striking workers being attacked cut with a shot of a bull being slaughtered creates a film metaphor suggesting that the workers are being treated like cattle. This meaning does not exist in the individual shots; it only arises when they are juxtaposed.

- At the end of Apocalypse Now the execution of Colonel Kurtz is juxtaposed with the villagers’ ritual slaughter of a water buffalo.

Intellectual Montage would make the viewer think more deeply about the connection between two separate images having them form new ideas, metaphors or symbols to the shots. The general trajectory between Intellectual Montage is Perception, Emotion, and Cognition. Eisenstein’s theory was based on a Japanese ideogram in which he created a third meaning within two separate shots which were the sum of all greater parts. For instance, a shot of a bird and a mouth would form a third meaning to the viewer which was to sing. The shots of an eye and water would form meanings of crying and the shots of a baby and a mouth would form the meaning of screaming. Drawn from the Marxist philosophical precept in which Dialectics=Thesis & Antithesis which = Synthesis. For example: Bourgeois/tsarist (thesis)+proletariat (antithesis)=outcome of classless society/revolution (synthesis).

Eisenstein’s style of Intellectual Montage is very similar to Kuleshov’s original theory called the Kuleshov Effect. The Kuleshov Effect was a experiment demonstrated in the 1910s and 20s where filmmaker’s recutted old footage of a close-up of actor Ivan Mozhuchin and repeatedly cut shots of other material like a bowl of soup, a crying baby or a dead woman’s body. Audiences would look at the same footage of Ivan Mozhuchin followed by a different shot and would bring a different conclusion to what they had to say about the scene. Eisenstein’s Intellectual Montage brought the power of editing to an even greater level and not only had the audience create different conclusions on what they saw on the screen, but they would create deeper symbolic meanings and metaphors that went outside the context of the film.

In his later writings, Eisenstein argues that montage, especially intellectual montage, is an alternative system to continuity editing. He argued that “Montage is conflict” (dialectical) where new ideas, emerge from the collision of the montage sequence (synthesis) and where the new emerging ideas are not innate in any of the images of the edited sequence. A new concept explodes into being. His understanding of montage, thus, illustrates Marxist dialectics.

Concepts similar to intellectual montage would arise during the first half of the 20th century, such as Imagism in poetry (specifically Pound’s Ideogrammic Method), or Cubism’s attempt at synthesizing multiple perspectives into one painting. The idea of associated concrete images creating a new (often abstract) image was an important aspect of much early Modernist art.

Eisenstein relates this to non-literary “writing” in pre-literate societies, such as the ancient use of pictures and images in sequence, that are therefore in “conflict”. Because the pictures are relating to each other, their collision creates the meaning of the “writing”. Similarly, he describes this phenomenon as dialectical materialism.

Eisenstein argued that the new meaning that emerged out of conflict is the same phenomenon found in the course of historical events of social and revolutionary change. He used intellectual montage in his feature films (such as Battleship Potemkin and October) to portray the political situation surrounding the Bolshevik Revolution.

He also believed that intellectual montage expresses how everyday thought processes happen. In this sense, the montage will in fact form thoughts in the minds of the viewer, and is therefore a powerful tool for propaganda.

Intellectual montage follows in the tradition of the ideological Russian Proletcult Theatre which was a tool of political agitation. In his film Strike, Eisenstein includes a sequence with cross-cut editing between the slaughter of a bull and police attacking workers. He thereby creates a film metaphor: assaulted workers = slaughtered bull. The effect that he wished to produce was not simply to show images of people’s lives in the film but more importantly to shock the viewer into understanding the reality of their own lives. Therefore, there is a revolutionary thrust to this kind of film making.

Eisenstein discussed how a perfect example of his theory is found in his film October, which contains a sequence where the concept of “God” is connected to class structure, and various images that contain overtones of political authority and divinity are edited together in descending order of impressiveness so that the notion of God eventually becomes associated with a block of wood. He believed that this sequence caused the minds of the viewer to automatically reject all political class structures.

Eisenstein discussed how a perfect example of his theory is found in his film October, which contains a sequence where the concept of “God” is connected to class structure, and various images that contain overtones of political authority and divinity are edited together in descending order of impressiveness so that the notion of God eventually becomes associated with a block of wood. He believed that this sequence caused the minds of the viewer to automatically reject all political class structures.

These five styles of Soviet Montage’s Cinema of Attractions has been influential for several future filmmakers’ as you still see forms of Soviet Montage being used in many present films today, most famously with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Pudovkin’s theory was in support of larger narrative action and of a series of linkage between shots. Vertov focused on rhythm in editing, and celebrated on how the eye of the camera recorded reality in contrast to the human eye. Sergei Eisenstein’s theory of montage is the most complex and most interesting of styles. Eisenstein developed three different forms of Montage. The first was Perceptual Montage which is a way of editing that would shock and affect the viewer. The second was Associational Montage which were comparisons or associations made through the sum of the shots.

One of the basic artistic precedents to the Soviet Montage movement was Russian Constructivism which was an art that fulfilled a clear social function and is not autonomous involving such artistic merits as architecture, graphic design and the theater. Constructivism incorporates the effect of technology and the industry on abstraction of forms such as the craftsman-worker (not genius or visionary.) The purity of geometric shapes such as lines and volumes communicates ideas more sharply, as the art becomes harnessed to social function and abstraction or utility. The artwork as machine within Constructivism counters the notion of art as organic, as art is seen as a synthesis between the dialectic nature and the industry/science which is seen in director Sergei Eisenstein’s writings. Constructivism refutes and challenges the notion of composition of passive decorative elements, which is a more direct construction of materials, or a manipulation of materials, as its component parts are activated and assembled, montage as “putting together.” The basic idea of Russian Constructivism is influenced by French Cubism & Italian Futurism, but these predecessors are not as overtly political as the Constructivist movement.

Russian Constructivism and these theories of Soviet Montages were greatly used in Battleship Potemkin, whether its the furious citizens yelling “Down with the tyrants!” and the shot is cut to clenched fists, or the captain threatening to hang mutineers from the yard, as the scene cuts to ghostly figures hanging from there. But the greatest uses of Soviet Montage are in the infamous Odessa Staircase massacre sequence, as director Sergei Eisenstein cuts between the frightened faces of the unarmed citizens, and then to the faceless troops with weapons, creating a contrasting argument for the people against the tsarist/czarist state. Other examples of this theory can be seen in this sequence whether its the defenseless civilians who are unable to flee and the cut to the citizen without legs, A military boot crushing a child’s lifeless hand and body and the horrifying reaction of the child’s helpless mother, a nurse with a pair of Pince-nez, but when the shot returns back to her the Pince-nez has been pierced by a bullet. And the most famous scene in this sequence (which was homaged most famously in Brian D Palma’s The Untouchables) when a mother is fatally shot while pushing an infant in a baby carriage and slowly falls to the ground pushing the baby carriage down the steps while it cuts to the violent slaughter of its fleeing crowd.

Eisenstein purposely used his editing techniques of Soviet Montage and the linkage and collision of shots as practical weapons as Eisenstein said in his own words: “solve the specific problem of cinema, and challenge audiences to experience ideas, emotions and sensations while being engrossed within a story.” Eisenstein put his techniques to full use with Battleship Potemkin, emotionally manipulating the audience in such a way as to feel sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and a emotional hatred for their cruel overlords. In the manner of most propaganda, the characterization is simple, so that the audience could clearly see with whom they should sympathize. The massacre on the steps, which never took place, was presumably inserted by Eisenstein for dramatic effect and to purposely demonise the Imperial regime.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

Dziga Vertov was born David Abelevich Kaufman and worked under a name meaning ‘spinning top.’ Vertov was an early pioneer in documentary film-making during the late 1920s. He belonged to a movement of filmmakers known as the kinoks, or kino-oki (kino-eyes). Vertov, along with other kinok artists declared it their mission to abolish all non-documentary styles of film-making. This radical approach to movie making led to a slight dismantling of film industry: the very field in which they were working. Most of Vertov’s films were highly controversial, and the kinok movement was despised by many filmmakers of the time. Vertov’s crowning achievement, Man with a Movie Camera, was his response to critics who rejected his previous film, A Sixth Part of the World. His brother, Mikhail Kaufman helped Vertov with the extraordinary cinematography for the film but unfortunately refused to ever work with his brother again after the film. He had another brother, Boris Kaufman, who later immigrated to Hollywood and eventually won an Oscar for filming Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront.

Critics declared that Vertov’s overuse of inter-titles in Man With the Movie Camera was inconsistent with the film-making style the kinoks subscribed to working within that context, and Vertov dealt with much fear in anticipation of the film’s release. He requested a warning to be printed in Soviet central Communist newspaper, Pravda, which spoke directly of the film’s experimental, controversial nature as Vertov was worried that the film would be either destroyed or ignored by the public eye. Because of doubts before the films screening, and great anticipation from Vertov’s pre-screening statements, Man With the Movie Camera gained a lot of interest before it was even shown. Upon the official release of Man with a Movie Camera, Vertov issued a statement at the beginning of the film:

(AN EXCERPT FROM THE DIARY OF A CAMERAMAN.)

FOR VIEWERS ATTENTION

THIS FILM PRESENTS AN EXPERIMENT IN THE CINEMATIC COMMUNICATION OF VISIBLE EVENTS

WITHOUT THE AID OF INTERTITLES

WITHOUT THE AID OF A SCENARIO

WITHOUT THE AID OF THEATER

THE EXPERIMENTAL WORK AIMS AT CREATING A TRULY INTERNATIONAL ABSOLUTE LANGUAGE OF CINEMA BASED ON ITS TOTAL SEPARATION FROM THE LANGUAGE OF THEATER AND LITERATURE.

Vertov’s message about the prevalence and unobtrusiveness of filming was not necessarily true, because cameras might have been able to go anywhere, but it was nearly impossible for them to be hidden and unnoticed, because of their extremely large size, and the noises the equipment made. To get footage using a hidden camera, Vertov and his brother and films co-author Mikhail Kaufman had to distract the subject with something else even louder than the camera filming them. The film also features a few obvious scenes that are staged and rehearsed, as the scene of a woman getting out of bed and getting dressed and the shot of chess pieces being swept to the center of the board which is a shot spliced in backwards so the pieces expand outward and stand in position.

Because some of the sequences were staged with stark experimentation, the film was attacked and criticized possibly as a result of its director’s frequent assailing of fiction film as a new opiate of the masses. And yet the film’s lack of ‘actors’ and ‘sets’ still made for a honest view of the everyday world; as the film is directed toward the creation of a genuine, international, purely cinematic language, entirely distinct from the language of theatre and literature, as Soviet citizens are shown at work and at play, and interacting with the machinery of modern life. To the extent that it can be said to have characters, they are the cameramen of the title, the film editor, and the modern Soviet Union they discover and present in the film.

Vertov’s silent films are mainly remembered for their stunning visuals and yet silents were not only about images alone. Years before Enthusiasm, the kinoks insisted that regardless if of whether you heard it or not, sound was a legitimate factor in editing which was called ‘Radio editing.’ The point of the kinoks theory was pressed as would. When Man With the Movie Camera was released it marked the transition from the ‘Cinema-Eye’ to the ‘Radio-Eye’, which term, as apposed to the ‘Radio-Ear, would signify the future of the two media, not exactly sound cinema, but rather an ideal alloy combining the immediacy of wireless with the visuality of film. As Vertov wanted this trajectory to suggest, the Knoki’s interest in images was giving way to a new interest in sound. This shift in interest responded to the general feeling in the Soviet Union of the late twenties that, politically, cinema was over and radio was in. In its reliance upon the Radio-Ear factor, Man with the Movie Camera invades the territory of sound cinema as far as a silent film can reach.

Some have mistakenly stated that many visual ideas, such as the quick editing, the close-ups of machinery, the store window displays, even the shots of a typewriter keyboard are borrowed from Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, which predates Man with the Movie Camera by two years, but as Vertov wrote to the German press in 1929, these techniques and images had been developed and employed by him in his Kino-Pravda newsreels and documentaries for the last ten years, all of which predate Berlin. Vertov’s pioneering cinematic concepts actually inspired other abstract films by Ruttmann and others.

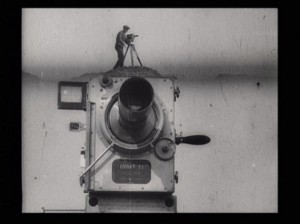

When Dziga Vertof’s Man with the Movie Camera was released in 1929, audiences had never seen a film quite like it. Its technical achievements in style and technique were truly astounding, as it emphasized that the magic of the camera could go anywhere. For instance, the film uses a scene of superimposing a shot of the cameraman setting up his camera tripod on top of a second gigantic camera, it superimposed the cameraman inside a gigantic beer glass, it filmed private voyeuristic moments of a woman getting out of bed and getting dressed, and even filmed such shocking personal moments of a woman giving birth. Many of the sequences in the film present people that seem to change size or appear over or underneath objects.

Vertov was one of the first to be able to find a mid-ground between a narrative media and a database form of media. He shot all the scenes separately, and had no intention of making the film into a regular theatrical movie with a traditional storyline. Instead, he took all these random clips that he photographed and put it in a database, which his wife Svilova later edited. The narrative and editing part of this process was all done by Vertov’s wife, as she had to go and sort through the random clips her husband shot, edit them and put them together in some form of structural order in which would make the most sense. The purpose of this was that Vertov wanted to break the traditional mold of a linear film that the world was comfortable in seeing, which is similar to what Jean-Luc Godard would do in the 60’s and Quentin Tarantino would do again in the 90’s.

Man With the Movie Camera is famous for its groundbreaking cinematic techniques that Vertov either invented, deployed or developed for the film; which ranged from double exposure, fast motion, slow motion, jump cuts, split screens, Dutch angles, extreme close-ups, hidden camera shots, tracking shots, footage played backwards, stop motion animations and a self-reflexive style which at one point features a split screen tracking shot with each sides having opposite Dutch angles. There is even a sequence where the action and the music comes to a halt and the frame freezes. We watch people suddenly stop working and we can hear the light diegetic sounds of the orchestra slowly start to pick up speed, and when the film feels it gathered enough power to continue the story, it suddenly kicks up momentum and the picture continues once again.

With all these revolutionary cinematic techniques, along with its fast moving speed and stylistic use of Soviet Montage and Russian Constructivism, Man With the Movie Camera comes across as a enthralling and slightly surreal like montage rather than a traditional linear motion picture. Many of its visually spectacular sequences of close-ups seem to capture a blend of dramatic aesthetics that could never be fully portrayed with words or in the world of talking pictures. “It stands as a stinging indictment of almost every film made between its release in 1929 and the appearance of Godard’s ‘Breathless‘ 30 years later,” the critic Neil Young wrote, “and Vertov’s dazzling picture seems, today, arguably the fresher of the two.” In the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, film critics voted Man with the Movie Camera the 8th best film ever made. Legendary critic Roger Ebert added it to his ‘Great Movies’ list and describes the editing aesthetics stating, “Most movies strive for what John Ford called “invisible editing” — edits that are at the service at the storytelling, and do not call attention to themselves. Considered as a visual object, Man With the Movie Camera deconstructs this process. It assembles itself in plain view. It is about itself, and folds into and out of itself. Godard is said to have introduced the jump cut, but Vertov’s film is entirely jump cuts.” The Alloy Orchestra presents a unique character of its own within the context of the film, and even though I haven’t heard Michael Nyman’s score for the Kino DVD edition, I doubt it could surpass the brilliance I heard by the Alloy Orchestra, (Which they performed following music instructions written by Dziga Vertov himself). Near the conclusion of its film Man With the Movie Camera builds up enough acceleration, tempo, and speed to reach the peak of its exciting conclusion which feels similar to the exciting peak of a carnival ride. Today Vertov’s Soviet Montage experiment can be now viewed as a historical ride back through time alongside The Man With the Movie Camera, as we become an active participant in seeing, preparing to see, and processing what we have seen, the pre-war years of the everyday Russian people.

With all these revolutionary cinematic techniques, along with its fast moving speed and stylistic use of Soviet Montage and Russian Constructivism, Man With the Movie Camera comes across as a enthralling and slightly surreal like montage rather than a traditional linear motion picture. Many of its visually spectacular sequences of close-ups seem to capture a blend of dramatic aesthetics that could never be fully portrayed with words or in the world of talking pictures. “It stands as a stinging indictment of almost every film made between its release in 1929 and the appearance of Godard’s ‘Breathless‘ 30 years later,” the critic Neil Young wrote, “and Vertov’s dazzling picture seems, today, arguably the fresher of the two.” In the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, film critics voted Man with the Movie Camera the 8th best film ever made. Legendary critic Roger Ebert added it to his ‘Great Movies’ list and describes the editing aesthetics stating, “Most movies strive for what John Ford called “invisible editing” — edits that are at the service at the storytelling, and do not call attention to themselves. Considered as a visual object, Man With the Movie Camera deconstructs this process. It assembles itself in plain view. It is about itself, and folds into and out of itself. Godard is said to have introduced the jump cut, but Vertov’s film is entirely jump cuts.” The Alloy Orchestra presents a unique character of its own within the context of the film, and even though I haven’t heard Michael Nyman’s score for the Kino DVD edition, I doubt it could surpass the brilliance I heard by the Alloy Orchestra, (Which they performed following music instructions written by Dziga Vertov himself). Near the conclusion of its film Man With the Movie Camera builds up enough acceleration, tempo, and speed to reach the peak of its exciting conclusion which feels similar to the exciting peak of a carnival ride. Today Vertov’s Soviet Montage experiment can be now viewed as a historical ride back through time alongside The Man With the Movie Camera, as we become an active participant in seeing, preparing to see, and processing what we have seen, the pre-war years of the everyday Russian people.