M (1931)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”M Fritz Lang” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Legendary director Fritz Lang took a gamble when making M, which tells the story of a child murderer in Berlin, as the film has been credited with forming two different genres: the serial killer movie and the police procedural. Lang’s earlier silent films including Metropolis were all worldwide successes, and by the year 1931, the Nazi Party were on their march in Germany. Lang lived in Berlin where the left-wing showed the plays of Bertolt Brecht, and although the Nazi Party were not yet in full control, Lang’s own wife would eventually become a member. I don’t know what Lang’s personal feelings of Germany were at that time, but the images in M were angry, vile, and extremely grotesque. It was as if Lang knew there was something brewing deep beneath the surface of German society, an evil that he felt he needed to express. Most of the sequences in M are of dirty smoke-filled conference rooms, disgusting dives, and corrupt unmoral men committing secret conspiracies in the shadows. The German people Lang casted in the film were highly unattractive caricatures, as if they were some part of a sick decaying society, greatly reminding me of the demonic faces of the accusing judges in Carl Dreyer’s silent The Passion of Joan of Arc. What I find highly fascinating is how identical the criminal and police worlds look from one another, as their business meetings are both shot in dark dreary rooms, their fat fingers clenching their cigars, creating such thick smoke that it’s difficult to visually make anyone out. Legendary film critic Roger Ebert states, “Certainly M is a portrait of a diseased society, one that seems even more decadent than the other portraits of Berlin in the 1930s; its characters have no virtues and lack even attractive vices. In other stories of the time we see nightclubs, champagne, sex and perversion. When M visits a bar, it is to show close-ups of greasy sausages, spilled beer, rotten cheese and stale cigar butts.” [fsbProduct product_id=’791′ size=’200′ align=’right’]What I get when witnessing these dirty, foul images was a artist who hated the Nazis and hated his country for permitting it to happen. M is supposedly based on the real-life case of serial killer Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf”, whose crimes took place in the 1920s, although Lang denied that he drew from this case. “At the time I decided to use the subject matter of M there were many serial killers terrorizing Germany — Haarmann, Grossmann, Kürten, Denke,” Lang told film historian Gero Gandert in a 1963 interview. M was Lang’s very first sound film and that new instrument is brilliantly put to use right from the very first frame, as you hear on the soundtrack the disturbing chant of a children’s elimination game being played in a Berlin courtyard. That scene is immediately followed by a heartbreaking sequence involving a mother pathetically waiting for her little girl to return home from school, all the while the mother frantically calls out her daughter’s name, while Lang cuts to images of an empty dinner plate, her daughter’s ball rolling through a patch of grass and the balloon that was bought for her ensnared in some telephone lines. Sound is also brilliantly used when implicating the presence of the killer, especially by hearing him compulsively whistling the tune from Peer Gynt over and over again, until the notes stand in for the murders. And yet Lang’s sparingly use of sound has never been better put to use then it had in the thrilling conclusion of the film, when actor Peter Lorre, (In one of his first screen performances) gives one of the greatest speeches in all of film history. M was a film which explored many controversial themes that many artists at that time wouldn’t dare tread, most importantly when asking audiences to try and understand the killer. Not sympathize with him but to understand him, as the child murderer pleads in his own defense, sweating in terror, crying out on how he cannot control or escape the murderous compulsions that consume him.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”M Fritz Lang” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Legendary director Fritz Lang took a gamble when making M, which tells the story of a child murderer in Berlin, as the film has been credited with forming two different genres: the serial killer movie and the police procedural. Lang’s earlier silent films including Metropolis were all worldwide successes, and by the year 1931, the Nazi Party were on their march in Germany. Lang lived in Berlin where the left-wing showed the plays of Bertolt Brecht, and although the Nazi Party were not yet in full control, Lang’s own wife would eventually become a member. I don’t know what Lang’s personal feelings of Germany were at that time, but the images in M were angry, vile, and extremely grotesque. It was as if Lang knew there was something brewing deep beneath the surface of German society, an evil that he felt he needed to express. Most of the sequences in M are of dirty smoke-filled conference rooms, disgusting dives, and corrupt unmoral men committing secret conspiracies in the shadows. The German people Lang casted in the film were highly unattractive caricatures, as if they were some part of a sick decaying society, greatly reminding me of the demonic faces of the accusing judges in Carl Dreyer’s silent The Passion of Joan of Arc. What I find highly fascinating is how identical the criminal and police worlds look from one another, as their business meetings are both shot in dark dreary rooms, their fat fingers clenching their cigars, creating such thick smoke that it’s difficult to visually make anyone out. Legendary film critic Roger Ebert states, “Certainly M is a portrait of a diseased society, one that seems even more decadent than the other portraits of Berlin in the 1930s; its characters have no virtues and lack even attractive vices. In other stories of the time we see nightclubs, champagne, sex and perversion. When M visits a bar, it is to show close-ups of greasy sausages, spilled beer, rotten cheese and stale cigar butts.” [fsbProduct product_id=’791′ size=’200′ align=’right’]What I get when witnessing these dirty, foul images was a artist who hated the Nazis and hated his country for permitting it to happen. M is supposedly based on the real-life case of serial killer Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf”, whose crimes took place in the 1920s, although Lang denied that he drew from this case. “At the time I decided to use the subject matter of M there were many serial killers terrorizing Germany — Haarmann, Grossmann, Kürten, Denke,” Lang told film historian Gero Gandert in a 1963 interview. M was Lang’s very first sound film and that new instrument is brilliantly put to use right from the very first frame, as you hear on the soundtrack the disturbing chant of a children’s elimination game being played in a Berlin courtyard. That scene is immediately followed by a heartbreaking sequence involving a mother pathetically waiting for her little girl to return home from school, all the while the mother frantically calls out her daughter’s name, while Lang cuts to images of an empty dinner plate, her daughter’s ball rolling through a patch of grass and the balloon that was bought for her ensnared in some telephone lines. Sound is also brilliantly used when implicating the presence of the killer, especially by hearing him compulsively whistling the tune from Peer Gynt over and over again, until the notes stand in for the murders. And yet Lang’s sparingly use of sound has never been better put to use then it had in the thrilling conclusion of the film, when actor Peter Lorre, (In one of his first screen performances) gives one of the greatest speeches in all of film history. M was a film which explored many controversial themes that many artists at that time wouldn’t dare tread, most importantly when asking audiences to try and understand the killer. Not sympathize with him but to understand him, as the child murderer pleads in his own defense, sweating in terror, crying out on how he cannot control or escape the murderous compulsions that consume him.

PLOT/NOTES

The story opens with a group of children playing a elimination game in the courtyard of an apartment building in Berlin. The children are singing a song about a child murderer that so far has not been caught and has previously been snatching and murdering children in the area: “Just you wait, it won’t be long. The man in black will soon be here. With his cleaver’s blade so true. He’ll make mincemeat out of you! Your out!”

The camera pans up to the homes of the children as one of the children’s mothers yells out, “I told you to stop singing that awful song! Didn’t you hear me? That same cursed song over and over!”

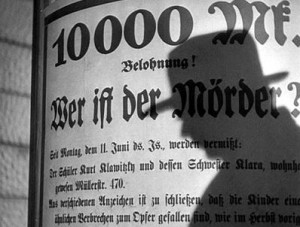

At the same time the scene cuts to one of the children’s mothers who is struggling carrying a heavy basket of laundry up a flight up stairs towards her apartment. While washing her clothes the mother patiently waits for her daughter to come home from school as she glances at the clock. She casually sets the dinner table with silverware. School is finally let out and young Elsie is finally heading home bouncing a ball, but first stops to read a reward’s poster, while bouncing the ball off the poster.

(10,000 marks reward-Who is the murderer?)

Suddenly the poster is overshadowed by a shadow of an adult figure.

“What a pretty ball you have there. Whats your name?”

“Elsie Beckmann.”

Tension gradually builds as her mother waits for Elsie to come home continuously looking at the clock. The next shot shows the suspicious shadow in a faraway shot buying a balloon for young Elsie from a blind street vendor as he whistles ‘In the Hall of the Mountain King’ by Edvard Grieg’ in the presence of the blind man. “Thank you! Thank you”, Elsie says as the two walk away together. When it is starts getting late Elsie’s mother begins to panic and asks the other children who arrive home if they seen Elsie. She slowly starts calling out for her daughter, as each new cry is more excessive and frantic.

“Elsie…Elsie…ELSIE!!!” While you hear the mother’s cries out for her daughter the audience is shown an empty seat at the dinner table where Elsie is supposed to be sitting for dinner, Elsie’s ball rolling through a patch of grass and the balloon that was bought for her ensnared in some telephone lines floating away.

There is no surprise on the identity of the murderer. The audience sees immediately, but his presence is either shot from farther away, showing his back to the camera, or you hear the sound of his whistling, “In the Hall of the Mountain King” by Edvard Grieg.

Right after the first abduction of Elsie it shows the serial killer whose name is Hans Beckert writing a letter to the newspapers and again whistling his trademark song in the privacy of his own apartment. Hans Beckert’s (Peter Lorre) letter writing reminds me of recent serial murderers in America like the Zodiac killer who taunted the public and the media by writing letters to them. His letter reads: “Because the police did not publish my letter, I am writing now directly to the press. Proceed with your investigations. All will soon be confirmed. But I’m not done yet!!”

All the while a newspaper man is outside his window selling newspapers shouting: “Extra! Extra! Who’s the murderer! The terror in our town has found a new victim. Certain evidence leads us to believe that this is the same murderer who has already claimed eight victims from among our city’s children. We must emphasize once again that it is now more than ever, every mother and father’s sacred duty to alert their children to this ever present danger and to the friendly guise it is likely to assume. A little candy, a toy or an apple can suffice to lure a child to his or her doom. Anxiety among the general public is heightened by the police’s failure to apprehend a suspect. But the police are faced with the almost impossible task of catching a criminal who left not the slightest clue behind. Who is the murderer? What does he look like? Where is he hiding? No one knows him, yet he is among us. Anybody sitting next to you could be the murderer.”

The city is in constant fear and everyone is suspect. On the street one child asks an adult what the time is, and the adult who gives her the time asks her where she lives and he is immediately attacked with many residents shouting, “He’s the murderer! Hold him!”

The letter that was written by Beckert reaches the paper and several newspaper’s are worried about scandal. The letters that were written by Beckert are taken to the police and used to extract clues using the new techniques of fingerprinting and handwriting analysis.

Meanwhile Beckert is in his apartment and looks at his reflection in the mirror, making hideous faces trying to form a grotesque monster that reflects how the people describe him on the streets and in the newspaper.

The city of course is full of fear and turmoil, meanwhile, the police, under Inspector Karl Lohmann pursues the killer using state of the art techniques, but seems to struggle with conflicting eye witnesses. He has police comb particular areas, searching homeless shelters and surveillancing railway stations.

“The cops!” Inspector Karl Lohmann starts to stage frequent raids and anyone who doesn’t have their papers in order are ordered to come down to the precinct, while many of the residents and businesses can’t get a moments peace. “Police orders! Nobody is to leave this establishment. Get your papers ready.” The police also begin to question and harass known criminals about their contacts. There’s so many police in the streets a pimp says, “There are more cops on the streets than girls.”

Under mounting pressure from city leaders, the police work around the clock.

All of this is of course disrupting underworld business so badly that Der Schränker (nicknamed The Safecracker) calls a meeting of the city’s top criminal bosses, at the same time as Inspector Lohmann calls a meeting of the commissioner and the top police officers.

Lang cuts from two separate business meetings, which are the cops and the criminals:

Der Schränker says at his criminal business meeting: “An outsider is ruining our business and our reputation. Measures taken by the police and the daily raids to catch this child murderer are hampering our activities to an almost unbearable degree. We can no longer tolerate the fact that we’re not safe now in any hotel, bar, cafe or even private home from the clutches of the police. Things must return to normal or we’ll go under. Our reputation is suffering as well. The police seek the murderer in our fold. Gentlemen, when I run head-on into an officer from the squad, he knows the potential risk and so do I . If either dies in the line of duty, fine. Occupational hazard. But we must draw a line between ourselves and this man they’re looking for! We conduct our business in order to survive but this monster has no right to survive! He must be killed, eliminated, exterminated! Without mercy or compassion. Gentlemen, our members must be able to go about their business again without frantic cops in their way at every turn. We have our connections. What if we put an article in the papers, that our syndicates, I mean, our organization doesn’t wish to be lumped in together with this pig, and that the cops should look for this guy somewhere else. He’s not even a real crook!”

Inspector Lohmann with the commissioner at their business meeting says: “Step up ID checks, comb the entire city, and raids…relentless, ever tougher raids! This man may be when not engaged in the actual act of killing…a harmless upstanding citizen. In his right mind, perhaps he plays marbles with his landlady’s kids or play cards with friends. There is perhaps one other way. I’m quite certain that information on the individual in question must already exist somewhere. Being the severely pathological case that his is, he has no doubt already had some kind of contact with the authorities. That’s why all health care facilities, prisons, clinics and insane asylums must be encouraged to cooperate with us unequivocally. We specifically need information on those released after being deemed harmless to society but who, due to their inclinations, could be the murderer.”

Getting an idea that the killer may have a previous psychiatric record Inspector Lohmann orders the compilation of a list of recently released psychiatric patients from mental asylums with a history of offenses against children and one of them on the list is Beckert.

While the police are doing their job the criminals are doing theirs by enlisting the help of the city’s beggars to divide up the city meter by meter and to keep watch over the children on the streets, to try and catch the murderer themselves. (Mainly so the police will eventually get off their back. Plus the criminals believe it’s disgraceful that the newspapers are lumping this child murderer in with the same group as the organized criminals and giving them a bad name.)

Eventually with police and criminals trying to catch this madman, a race develops between the two on who can find the killer first.

As the police visit the home of each person on the list of recently known psychiatric patients, the officer checking Beckert’s home discovers two clues in the rooms of Beckert, who is out of his apartment at the time. The same cigarette brand that was found next to one of the bodies of the children is found in Beckert’s trash, and the wooden window ledge in Beckert’s apartment with red pencil, is identical to what the killer was using when writing his letters to the newspaper.

Meanwhile Beckert is out on the street looking in a shop window and notices a young girl who appears in the reflection. Following her down the street, he is forced to stop when the girl meets her mother. But he has been aroused and at a café he hurriedly drinks two cognacs, as if to quench the desires he has. When he encounters another young girl, his temptations take over and the face Beckert portrays is a man who has an urge that’s so unstoppable and overwhelming, that it consumes him.

Giving into his temptations, he confronts the girl but Beckert makes the mistake of compulsively whistling his characteristic tune again near the blind street vender who sells balloons. “That’s odd,” the street vender says. “I’ve heard that before. It was…It was…(Interesting enough, Lorre did not know how to whistle so Lang is the one who is heard.) The blind vender remembers that tune from the last incident and alerts one of his beggar friends, who tails the killer with assistance from other beggars he alerts along the way.

While one of the beggars is following Beckert with the young girl, he watches the murderer take the little girl to a candy store. After buying the girl candy the two leave as Beckert takes out a knife to cut open an orange, throwing the orange peel on the ground. To track Beckert, the beggar following him marks a large letter M (Which means Murder) on his hand with chalk and gets it to rub off on the back of Beckert’s coat by pretending to slip on the orange peel that Beckert had just dropped and slapping the murderer’s shoulder. “Are you crazy, throwing orange peels on the ground? A man could fall and break his neck!” the beggar says.

When Beckert finally realizes he is being followed and when seeing the chalk mark of M on his shoulder, he tries to get away, by running from the beggars in the streets and eventually hiding inside a large office building.”We can’t let him get away now! If he slips away!”

After receiving a call from the lookouts, Der Schränker assembles a team of criminals to search the building after all the day workers have left.

Meanwhile Inspector Lohmann and several of his officers wait inside Beckert’s apartment for him to return home to make Beckert’s arrest.

Der Schränker’s men tie up and torture the office building security guard for information, capture the remaining watchmen, then explore the office building where Beckert is hiding, as they search from the coal cellar to the attic. “There he is! The dog!” They finally capture Beckert with seconds to spare after one of the watchmen trips the silent alarm for police, and the crooks narrowly escape with their prisoner before the police arrive.

One, however, is captured and eventually tricked into revealing the purpose of the break-in (nothing was stolen) and the location on where the criminals would be taking Beckert .

The criminals drag Beckert to an abandoned distillery to face a assembled court full of criminals and several victims of the families.

The camera pans across to show all their cold faces looking at Beckert with hate and contempt in complete silence. (Ironically most of the people in this scene were real criminals that Lang used.) Beckert begs to the assembled court, “Gentlemen, I beg of you! I don’t even know what you want with me. I beg you! Let me go! This whole thing must be a mistake!”

The blind vender appears from behind him and grabs Beckert’s shoulder, saying, “No mistake.” He gives Beckert the balloon that he bought the dead Elsie girl and says, “You recognize this? You bought a balloon just like this for little Elsie Beckmann. Just like this one.”

Der Schränker is the man in charge of the assembly and he puts Beckert on a form of trial before he’s put to death. “Where did you bury little Marga Perl, you bastard?” Der Schränker starts showing photographs of all the dead children and Beckert tries to make a run for it but is stopped. “Kill him! The rapid dog!” People in the crowd start yelling for Beckert’s execution.

Beckert is given a lawyer, who gamely argues in his defense but fails to win any sympathy from the jury. “Do you all want to kill me?” Beckert asks the crowd. “You want to just wipe me out?” Der Schränker tells him that they simply want to put him out of commission. Beckert cries, “But you can’t murder me just like that! I demand to be handed over to the police! I demand to be brought before a real court of law!” Everyone in the crowd starts laughing. Der Schränker says:

“You’d like that wouldn’t you? So you can plead insanity and spend the rest of your life being cared for by the state. And then you break out of the asylum or receive a pardon, and your happy as can be, free to kill with impunity, protected by law on grounds of insanity… and your back to chasing little children! You must be taken out of action! You must go!”

“I can’t help it! I can’t…I really can’t…help it! What would you know? What are you talking about? Who are you anyway? Who are you? All of you? Criminals. Probably proud of it too, proud you can crack a safe or sneak into houses or cheat at cards. All of which it seems to me you could just as easily give up if you had learned something useful, or if you had jobs or if you weren’t such lazy pigs. But me? Can I do anything about it? Don’t I have this cursed thing inside me? This fire, this voice, this agony?”

“So you mean to say, you have to kill?”

“I have to roam the streets endlessly, always sensing that someone’s following me. It’s me! I’m shadowing myself! Silently…but I still hear it. Yes, sometimes I feel like I’m tracking myself down. I want to run…run away from myself! But I can’t! I can’t escape from myself! I must take the path that it’s driving me down and run and run down endless streets! I want off! And with me run the ghosts of the mothers and children. They never go away. They’re always there! Always! Always! Except…when I’m doing it…when I…Then I don’t remember a thing. Then I’m standing before a poster, reading what I’ve done. I did that? I don’t remember a thing! But who will believe me? Who knows what it’s like inside me? How it screams and cries out inside me when I have to do it! Don’t want to! Must! Don’t want to! Must! And then a voice cries out, and I can’t listen anymore! Help! I can’t! I can’t!!!”

“The accused have stated that he can’t help himself. In other words, he must commit murder. With that he has pronounced his own death sentence. A man who claims that he’s compelled to destroy the lives of others…such a man must be extinguished like a bonfire! Such a man must be obliterated! Wiped out!”

The lawyer announces that since Beckert is under the very nature of compulsion, that relieves him of responsibility of his actions, and a man cannot be punished for that. “I’m saying that this man is sick, and you turn a sick man over to a doctor, not an executioner.” Der Schränker asks who will guarantee his cure, and if he one day breaks out of the asylum, the murders will start all over again. “No one has a right to kill a man who cannot be held responsible for his crimes!” yells the lawyer.

The crowd laughs and one of the mothers comes forward saying, “You never had kids, huh? Then you never lost any either. But if you wanna know what it’s like when a little child is taken from you, just ask the parents whose kids he took away! Ask ’em about the days and nights not knowing what had happened, and later when they finally found out…Why don’t you ask the mothers? You should ask the mothers! Think you’d get mercy from any of them for murdering their kids! No mercy for the killer!”

The people all yell out, “Kill the monster! Slaughter the bastard! Put the animal to death! Rub him out! Waste him! Get rid of him! Annihilate the monster!” The lawyer says he will not allow a murder to be committed in his presence, demanding that the human being be afforded the same protection under the law rendered the common criminal.

The people don’t listen and are about to charge the murderer, but suddenly stop in their tracks and put their hands up when Inspector Lohmann and the police arrive. They arrest Beckert and take him to trial.

During the trial, a grieving mother says, “This will not bring our children back. One has too keep closer watch over the children…”

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

Much of the style that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari embodied was of German Expressionism, which was one of many creative styles and movements that came out of Germany after their defeat in World War I. UFA studios which was Germany’s principal film studio at that time, decided for the film industry to go private which largely confined Germany and isolated the country from the rest of the world. In 1916, the government had banned any foreign films in the nation, and so the demand from theaters to generate films led to the rise of film production from 24 films released in 1914 to a high 130 films in 1918.

German Expressionism and its aesthetics was first derived from German Romanticism and of architecture, painting, and of the stage, most famously from German set designers Herman Warm, Walter Rorhig, and Walter Reimann. Much of German Expressionism’s style and design expressed interior realities via exterior realities and emotionalism rather than objectivity or realism. Many films of German Expressionism used bizarre set designs with wildly non-realistic, geometrically absurd sets, along with designs painted on walls and floors to represent lights, shadows, and objects. The world that characters inhabit in a German Expressionism film are full of exaggerated landscapes and environments of abstract shapes, angles, shadows and distorted sets. The building architecture is off kilter, jagged and many of the props seem to be geometrically off-balance. This unusual visual look is intentional off course to give the viewer a feeling of inner emotional reality rather than realism. It’s unsettling sets of instability gives the feeling of claustrophobia and space collapsing around the viewer.

The actor’s in German Expressionism films usually wear heavy make-up, their acting is greatly exaggerated and their movements are jerky and unnatural to blend in with the stylistic and abstract environment. German Expressionistic’s odd and distorted style are as unrealistic as the dilution of its main character who’s narrative is a good contrast to its style as it revolves around such themes as psychology, fantasy, madness, betrayal and murder as its creators used extreme distortions in expression to show an inner emotional reality rather than realism or what was on the surface. Most films that helped categorize German Expressionism include several of Fritz Lang’s silent films most importantly Metropolis, M and Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel are also considered landmarks of German Expressionism, with some critics looking at the aesthetics of German Expressionism as the early beginnings of American film-noir.

ANALYZE

In 1931 Weimar Germany, the public was on the verge of hysteria over a series of gruesome murder cases. Though M may now seem almost a parable, at the time it was seen as a “ripped from the headlines” drama. The following article by the filmmaker himself originally appeared in the German newspaper Die Filmwoche on May 20, 1931. It was reprinted in Fritz Lang: His Life and Work.

Striding in seven-league boots, the miracles we experience by the hour in our everyday lives have caught up with the 1,001 tales of Scheherazade and left them behind. Or do you think that any remotely normal Central European who needs to get from Berlin to Paris as fast as possible would choose a winged horse if a racing car were available, or a flying carpet if he could take an airplane? When it comes to surpassing the dreams in Aladdin’s garden, there is no need even to think of Baby Green’s subterranean swimming paradise, with its magnificent displays of coral, glass, gold, and lapis lazuli. The Haus Vaterland at Potsdamer Platz or a Luna Park with a semblance of modern management are quite sufficient in the end. You only have to keep your eyes open for what is around you! All the newspapers report human tragedies and comedies, anomalies and universalities, on a daily basis, and these reports are so fantastic, so accidental and romantic—or whatever else you like to call them—that no dramaturge for a big corporation would dare to suggest such material, lest he be confronted with a resounding chorus of derisive laughter at the improbable, chance, or kitschy conflicts. That’s life. So I thought it fitting to reflect the rhythm of our times, the objectivity of the age in which we are living, and to make a film based entirely on factual reports.

Anyone who makes the effort to closely read the newspaper reports about the major homicide cases of the past few years—e.g., the ghastly double murder of the Fehse siblings in Breslau, the Husmann case, or the case of little Hilde Zäpernick, three crimes that are unsolved to this day—will find a strange similarity of events, circumstances that repeat themselves almost as if natural laws were at work, such as the dreadful psychotic fear of the general public, the self-accusations of the mentally inferior, denunciations unleashing the hate and the jealousy that have built up over years of living side by side, attempts to feed the police investigators false leads, sometimes on malicious grounds and sometimes out of excessive zeal.

Bringing out all these things on the screen, separating them from the incidentals, seems to me to confront a film, a film based on factual reports, with a more substantial responsibility than the artistic reproduction of events: the responsibility of sounding a warning from real events, of educating, and in this way ultimately having a preventive effect. It would go beyond the scope of this brief comment to dwell on the means open to such a film to draw attention to the dangers that, given an incessantly growing crime rate, spell threat and, sadly, all too often, disaster for people at large, children and youngsters in particular; to illuminate the ordinariness and banality with which they announce themselves; to educate; and, most important of all, to have a preventive impact. It hardly needs stating that the artistic reproduction of such a murder case implies not only the presentation of events in concentrated form but also the extraction of typical phenomena and the typification of the killer. For this reason, the film should give the impression at certain points of a moving spotlight, revealing with greatest clarity the thing on which its cone of light is directed at the time: the grotesqueness of an audience infected with a murder psychosis, on the one hand, and the gruesome monotony with which an unknown murderer, armed with a few candies, an apple, a toy, can spell disaster for any child in the street, any child outside the protection of his family or the authorities.

There is one motif used in this case that seems to illustrate particularly well how fantastic real events have become: the idea that the criminal caste, Berlin’s underworld, would take to the streets on its own initiative to seek out the unknown murderer, so as to evade greater police activity, is taken from a factual newspaper report and seemed to me such compelling cinematic material that I lived in constant fear that someone else would exploit this idea before me.

If this film based on factual reports helps to point an admonishing and warning finger at the unknown, lurking threat, the chronic danger emanating from the constant presence among us of compulsively and criminally inclined individuals, forming, so to speak, a latent potential that may devour our lives in flames—and especially the lives of the most helpless among us—and if the film also helps, perhaps, even to avert this danger, then it will have served its highest purpose and drawn the logical conclusion from the quintessential facts assembled in it.

-Fritz Lang

I don’t know what Lang’s personal feelings of Germany were at that time of making M, but the images in M were angry, vile, and extremely grotesque. It was as if Lang knew there was something brewing deep beneath the surface of German society, an evil that he felt he needed to express. Most of the sequences in M are of dirty smoke-filled conference rooms, disgusting dives, and corrupt unmoral men committing secret conspiracies in the shadows. The German people Lang casted in the film were highly unattractive caricatures, as if they were some part of a sick decaying society, greatly reminding me of the demonic faces of the accusing judges in Carl Dreyer’s silent The Passion of Joan of Arc.

What I find highly fascinating is how identical the criminal and police worlds look from one another, as their business meetings are both shot in dark dreary rooms, their fat fingers clenching their cigars, creating such thick smoke that it’s difficult to visually make anyone out. Lang portrays both worlds equally as ugly, that its difficult to tell apart the cops and the criminals. Legendary film critic Roger Ebert states, “Certainly M is a portrait of a diseased society, one that seems even more decadent than the other portraits of Berlin in the 1930s; its characters have no virtues and lack even attractive vices. In other stories of the time we see nightclubs, champagne, sex and perversion. When M visits a bar, it is to show close-ups of greasy sausages, spilled beer, rotten cheese and stale cigar butts.” What I get when witnessing these dirty, foul images was a artist who hated the Nazis and hated his country for permitting it to happen.

Fritz Lang is one of the greatest directors of all time and along with the style of German Expressionism, he developed some of the greatest films in the world. Many of the early silent films Lange created included his thriller Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, and his fantasy epic Die Nibelungen. In 1927 Fritz Lang released the expressionist science-fiction epic Metropolis which was one of the most expensive and influential films of the silent era. Throughout the decades Metropolis as been regarded as the quintessential science-fiction film, and was the first feature length science-fiction film that pioneered the genre. Lang’s next film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in 1933 was a sequel to his famous character Dr. Mabuse in the silent classic The Gambler. This story continued Dr. Mabuse’s story where he’s now in an insane asylum and working his crimes from the inside, but the difference in that film is that the character knows how to brainwash and hypnotize his victims to commit horrible crimes which was unmistakably thought of as Nazism. When Lang released his film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse it was banned in Germany by the censors. When Adolf Hitler acquired power, Joseph Goebbels became minister of the Ministry of Propaganda and offered Lang full control of the nation’s film industry if he would come on board with the Nazis, so Fritz Lang instead fled on a midnight train to America. In an amazing interview with Fritz Lang by William Friedkin on the blu ray Criterion of M, Fritz Lang details the night he fled Germany; which is absolutely spellbinding.

M has been credited with forming two different genres: the serial killer movie and the police procedural. Watching the police go through the many procedures of using state of the art techniques, like finger prints, handwriting comparisons, questioning eye witnesses, taking statements, combing particular checkpoints, committing police raids on homes and businesses, and cutting from two separate business meetings between the cops and the criminals is fascinating, and extremely ahead of its time, especially for 1931.

A lot of people believe M paved its way into film noir in the early 40’s in America, for which I’m not at all surprised since Lang prospered in the states making some of the greatest noir films from the early 40s to the early 50s. Fritz Lang’s best American noir films are You Only Live Once with Henry Fonda, which is slightly based on Bonnie and Clyde, Fury with Spencer Tracy, which similar to the themes of M which explores the ignorance of mob violence and what it can escalate to, Scarlett Street with Edward G. Robinson, who plays a wealthy man being conned by a beautiful woman and his best American film The Big Heat with Glenn Ford, which is about a cop seeking revenge on the murder of his wife.

They’re several themes in M that are still relevant in today’s society, like the force of mob brutality without wanting to use justice in a court of law. But it is also historically relevant on Fritz Lang’s thoughts on the time and place of German society in the early 30’s. It portrays how the German people can easily be brainwashed and manipulated into actually believing that violence is just and moral. Many of these metaphors on violence and mob mentality can be slight foreshadowings on Nazism, in which a mob or a large number of people could influence an individual’s moral decision making and have a person mindlessly go through or carry out something that they could never do alone, but only with others. Critic Roger Ebert made a good point in saying that: “Elsewhere in the film, an innocent old man, suspected of being the killer, is attacked by a mob that forms on the spot. Each of the mob members was presumably capable of telling right from wrong and controlling his actions (as Beckert was not), and yet as a mob they moved with the same compulsion to kill. There is a message there somewhere. Not ‘somewhere’, really, but right up front, where it’s a wonder it escaped the attention of the Nazi censors.”

M was also incredibly groundbreaking and extremely ahead of its time, as it took several risks on discussing the theme of serial killers, at a time when most thought of it as taboo. Most Americans were afraid to discuss a controversial subject like that in the cinema and instead used those fears to create fictional supernatural boogie-men. In the 30’s those fears were created through fantasy creations like the Universal Studio monsters of Dracula and Frankenstein. In the 50’s, the fear of the cold-war, and of nuclear annihilation created more mutated creatures and space aliens like The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Creatures of the Black Lagoon. It wasn’t until 30 years later that the theme of real life serial killers would finally be examined and discussed once again, done by none other than the great Alfred Hitchcock in his horror masterpiece Psycho and also Michael Powell’s in his British voyeuristic classic Peeping Tom. Now serial murderers are a normal subject that is used in Hollywood formulas, which brought us some of our smartest and scariest films like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, The Vanishing, The Silence of the Lambs, Zodiac and Se7en. Not only are these films very scary and highly entertaining but they also explored the intriguing concepts of pathology, and of the human mind.

M is supposedly based on the real-life case of serial killer Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf”, whose crimes took place in the 1920s, although Lang denied that he drew from this case. “At the time I decided to use the subject matter of M there were many serial killers terrorizing Germany — Haarmann, Grossmann, Kürten, Denke,” Lang told film historian Gero Gandert in a 1963 interview. The murders that occur in M are all off-screen, including the heartbreaking opening sequence involving a mother pathetically waiting for her little girl to return home from school, all the while the mother frantically calls out her daughter’s name, while Lang cuts to images of an empty dinner plate, her daughter’s ball rolling through a patch of grass and the balloon that was bought for her ensnared in some telephone lines. Lang did not show any acts of violence or deaths of children on screen and later said by only suggesting violence he forced each individual member of the audience to create the gruesome details of the murder according to his personal imagination. There is no suspense about the murderer’s identity. The killers identity is revealed early in the film as we see Beckert writing letters to the newspapers and in one classic sequence making hideous faces in a mirror by pulling the corners of his mouth, trying to form a grotesque monster that reflects how the people describe him on the streets and in the newspaper.

M was Lang’s very first sound film and that new instrument is brilliantly put to use right from the very first frame, as you hear on the soundtrack the disturbing chant of a children’s elimination game being played in a Berlin courtyard. Many early talkies felt they had to talk all the time, but Lang used this new found technology wisely. Lang purposely left several sequences silent, which made those scenes much more eerie and mysterious. M has a dense and complex soundtrack that includes a narrator, sounds occurring off camera and motivating action and suspenseful moments of silence before sudden noise. Lang allowed his camera to silently prowl through the streets and dives, providing a rat’s-like point of view, and only contributed sound if only to emphasize something. Lang was also able to make fewer cuts in the films editing, since sound effects could now be used to inform the narrative. Sound is brilliantly used when implicating the presence of the killer, especially by hearing him compulsively whistling the tune from Peer Gynt over and over again, (actor Peter Lorre could not whistle, and so it is actually Lang who is heard) until the notes stand in for the murders, and it becomes his usual M.O. One of the film’s most spectacular shots is utterly silent, as the captured killer is dragged into a basement to be confronted by the city’s assembled criminals and families of the victims, and the camera pans across them in complete silence to show all their cold faces looking at Beckert with hate and contempt. (Ironically most of the people in this scene were real criminals that Lang used.). And yet Lang’s sparingly use of sound has never been better put to use then it had in the thrilling conclusion of the film, when actor Peter Lorre gives one of the greatest speeches in all of film history.

M is considered actor Peter Lorre’s first real screen performance and I don’t know if it’s the one he wanted to be truly remembered for but it’s the one that most people acknowledge. Peter Lorre at the time of M was 26, overweight, baby-faced, and portrayed a sweaty nervous expression that gave off a man living a secret life. Like Lang he eventually fled Germany to America and had a great long career staring in some of the greatest American films, (even though for a while he was usually type-cast as the villain) most famously the ones with Humphrey Bogart like Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon and Beat the Devil.

M was restored in 2000 by the Netherlands Film Museum in collaboration with the Munich Film Archive, the Cinemateque Suisse, Kirsch Media and ZDF/ARTE, with Janus Films releasing the 109-minute version as part of its Criterion Collection using prints from the same period from the Cinemateque Suisse and the Netherlands Film Museum. A complete print of the English version with Lorre recording his own voice and selected scenes from the French version were included in the 2010 Criterion Collection blu ray release of the film. Some of the shots in the English version are completely different from the German version which makes for a fascinating viewing and comparison. M was ranked #33 in Empire magazines The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema in 2010, and director Fritz Lang considered M to be his finest work, because of the social criticism in the film. In 1937, he told a reporter that he made the film “to warn mothers about neglecting children.” M is one of the greatest and most influential films of all time and is one of my top 10 favorite films. M was a film which explored many controversial themes that many artists at that time wouldn’t dare tread, (and wouldn’t for another 30 years) most importantly when asking audiences to try and understand the killer. Not sympathize with him but to understand him, as in the end of the film, the child murderer pleads in his own defense, sweating in terror, his wide eyes crying out on how he cannot control or escape the murderous compulsions that consume him. “I can’t help myself! I haven’t any control over this evil thing that’s inside of me! The fire, the voices, the torment! Who knows what it’s like to be me?” I have always believed that in a film it’s more interesting to reveal the villain to the audience early on and have the audience try to understand how they work, think, and feel. Most films make the villain’s identity (especially in horror films) a mystery until the very end, and throughout the story simply label them as a nameless figure with a hockey mask, but I believe that’s a cheap and unintelligent cop-out for a really good story. Some of the best films show the identity of the villain earlier on like in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs or George Sluizer’s The Vanishing, and it’s more interesting to learn why the villain is doing these horrible acts then to make them some one-dimensional faceless killer hiding in the dark with a butcher knife. That’s why films like M, The Silence of the Lambs, and Se7en are more fascinating than most thrillers because you get inside the head of the villain, and you try and figure why they do what they do. I truly believe the reason why most films don’t want to explore the mind of a killer is because people are simply afraid to explore that dark side of the psyche, and learn the unfortunate truth: That these monsters who commit such unthinkable and heinous crimes are people like us, they are our neighbors, our friends and loved ones, which is why we have created the fantastical supernatural characters such as Dracula, Michael Myers, and Lucifer, because to simply label them as ‘monsters’ is much more comforting.

M was restored in 2000 by the Netherlands Film Museum in collaboration with the Munich Film Archive, the Cinemateque Suisse, Kirsch Media and ZDF/ARTE, with Janus Films releasing the 109-minute version as part of its Criterion Collection using prints from the same period from the Cinemateque Suisse and the Netherlands Film Museum. A complete print of the English version with Lorre recording his own voice and selected scenes from the French version were included in the 2010 Criterion Collection blu ray release of the film. Some of the shots in the English version are completely different from the German version which makes for a fascinating viewing and comparison. M was ranked #33 in Empire magazines The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema in 2010, and director Fritz Lang considered M to be his finest work, because of the social criticism in the film. In 1937, he told a reporter that he made the film “to warn mothers about neglecting children.” M is one of the greatest and most influential films of all time and is one of my top 10 favorite films. M was a film which explored many controversial themes that many artists at that time wouldn’t dare tread, (and wouldn’t for another 30 years) most importantly when asking audiences to try and understand the killer. Not sympathize with him but to understand him, as in the end of the film, the child murderer pleads in his own defense, sweating in terror, his wide eyes crying out on how he cannot control or escape the murderous compulsions that consume him. “I can’t help myself! I haven’t any control over this evil thing that’s inside of me! The fire, the voices, the torment! Who knows what it’s like to be me?” I have always believed that in a film it’s more interesting to reveal the villain to the audience early on and have the audience try to understand how they work, think, and feel. Most films make the villain’s identity (especially in horror films) a mystery until the very end, and throughout the story simply label them as a nameless figure with a hockey mask, but I believe that’s a cheap and unintelligent cop-out for a really good story. Some of the best films show the identity of the villain earlier on like in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs or George Sluizer’s The Vanishing, and it’s more interesting to learn why the villain is doing these horrible acts then to make them some one-dimensional faceless killer hiding in the dark with a butcher knife. That’s why films like M, The Silence of the Lambs, and Se7en are more fascinating than most thrillers because you get inside the head of the villain, and you try and figure why they do what they do. I truly believe the reason why most films don’t want to explore the mind of a killer is because people are simply afraid to explore that dark side of the psyche, and learn the unfortunate truth: That these monsters who commit such unthinkable and heinous crimes are people like us, they are our neighbors, our friends and loved ones, which is why we have created the fantastical supernatural characters such as Dracula, Michael Myers, and Lucifer, because to simply label them as ‘monsters’ is much more comforting.