Life of Oharu, The (1952)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Kenji Mizoguchi” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]The film begins on a chill dawn in the dark outskirts of Kyoto, while the heroine named Oharu, her face hidden behind a fan, encounters some of her fellow prostitutes. “It’s hard for 50-year-old women to pass as 20,” she observes. The women ultimately find a friend who has built a fire, and huddle around it. A fellow prostitute says to Oharu, “You used to serve in the imperial courts. Did you ever think you’d end up like this? How did you fall so far?” Oharu ignores the woman and walks away, wandering into a Buddhist temple. One of the images of the Buddha dissolves into the face of a man who was a ‘forbidden love’ during Oharu’s youth; and then a flashback begins which will be the first of many that will explore the life of Oharu. And begins one of the most tragic stories about a woman presented within the cinema, as the legendary Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi uses the experiences of a struggling courtesan to examine the issues of sex, class, and rigid feudal hierarchy in Japanese society during the Edo period. Unfortunately for the protagonist Oharu, things turn out badly for any social role she chooses to assume herself in, whether its court lady, concubine, courtesan, wife, nun, or common prostitute; Oharu can never catch a break under feudal, mercantile, and patriarchal rule. I love Japanese cinema especially the works of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu and the great and most underrated of the three, Kenji Mizoguchi. The young French critics of the Cahiers du cinema were crazy about his work, and they thought Mizoguchi was not only the greatest of Japanese masters, but high in the ranks of the greatest filmmakers who have ever practiced the art. [fsbProduct product_id=’790′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Some critics have questioned Mitzoguchi’s feminism, as many have speculated that he harbored feelings of guilt regarding women and sought their forgiveness through the messages of his films. However that may be, he was a critic of male hierarchy and Japanese society, whose wrongs were for him most evident in the wrongs done to women. Mizoguchi made the subject of prostitution into a frequent theme throughout his work such as in Streets of Shame, Ugetsu, and Sansho the Bailiff, and it has been claimed that The Life of Oharu was one of Mizoguchi’s favorite projects, probably because it drew from roots in his own life. Mizoguchi was known to frequent brothels, not simply to purchase favors, but to socialize with their workers. These brothels made a great impression on the director, and that even his own sister Suzo, who raised him, was ultimately sold by their father as a geisha, which frightfully mirrors the tragic fate of the main protagonist in the film.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Kenji Mizoguchi” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]The film begins on a chill dawn in the dark outskirts of Kyoto, while the heroine named Oharu, her face hidden behind a fan, encounters some of her fellow prostitutes. “It’s hard for 50-year-old women to pass as 20,” she observes. The women ultimately find a friend who has built a fire, and huddle around it. A fellow prostitute says to Oharu, “You used to serve in the imperial courts. Did you ever think you’d end up like this? How did you fall so far?” Oharu ignores the woman and walks away, wandering into a Buddhist temple. One of the images of the Buddha dissolves into the face of a man who was a ‘forbidden love’ during Oharu’s youth; and then a flashback begins which will be the first of many that will explore the life of Oharu. And begins one of the most tragic stories about a woman presented within the cinema, as the legendary Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi uses the experiences of a struggling courtesan to examine the issues of sex, class, and rigid feudal hierarchy in Japanese society during the Edo period. Unfortunately for the protagonist Oharu, things turn out badly for any social role she chooses to assume herself in, whether its court lady, concubine, courtesan, wife, nun, or common prostitute; Oharu can never catch a break under feudal, mercantile, and patriarchal rule. I love Japanese cinema especially the works of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu and the great and most underrated of the three, Kenji Mizoguchi. The young French critics of the Cahiers du cinema were crazy about his work, and they thought Mizoguchi was not only the greatest of Japanese masters, but high in the ranks of the greatest filmmakers who have ever practiced the art. [fsbProduct product_id=’790′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Some critics have questioned Mitzoguchi’s feminism, as many have speculated that he harbored feelings of guilt regarding women and sought their forgiveness through the messages of his films. However that may be, he was a critic of male hierarchy and Japanese society, whose wrongs were for him most evident in the wrongs done to women. Mizoguchi made the subject of prostitution into a frequent theme throughout his work such as in Streets of Shame, Ugetsu, and Sansho the Bailiff, and it has been claimed that The Life of Oharu was one of Mizoguchi’s favorite projects, probably because it drew from roots in his own life. Mizoguchi was known to frequent brothels, not simply to purchase favors, but to socialize with their workers. These brothels made a great impression on the director, and that even his own sister Suzo, who raised him, was ultimately sold by their father as a geisha, which frightfully mirrors the tragic fate of the main protagonist in the film.

PLOT/NOTES

A street-walker named Ohara Ouri (Kinuyo Tanaka) tells another that a woman of 50 can’t make herself look 20 as the group of prostitutes walk towards a warm fire as one of the woman asks Oharu, “You used to serve in the imperial courts. Did you ever think you’d end up like this? How did you fall so far?” Oharu tells her not to speak about the past, as she ultimately wanders into a Buddhist temple and one of the images of the Buddha dissolves into a young man. It than flashes back to events of Oharu’s life.

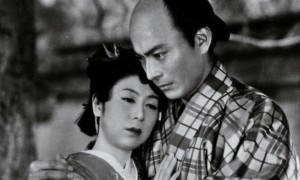

A much younger Oharu is invited to Lord Kiunokoji’s to discuss a certain political matter. She agrees and when arriving his nobleman Lord Katsunosuke (Toshiro Mifune) expresses his love for Oharu, but she turns him down due to their class difference. Katsunosuke wont give up saying, “Lady Oharu, a human being…no, a woman can only be happy if she marries for love. Rank and money don’t mean happiness.” Lord Katsunosuke admits that his Lord isn’t coming, and he only wanted to see Oharu to express his deep love for her. Oharu tells Katsunosuke that the courts and her father would never allow the two of them together and ultimately Oharu gives in to Katsunosuke’s love for her.

When the two lovers are caught together Oharu is taken to the magistrate. Since Oharu violated protocol she is banished from the city of Kyoto and never to return, including sentencing her parents to exile. Her father Lord Shinzaemon blames Oharu for single-handedly destroying his noble family’s honor. “Why is it wrong for a man and woman to fall in love? Why is it immoral” Oharu asks.

Katsunosuke is executed for his punishment as his last words for Oharu are: “Please find a good man and make a happy home. But be sure to marry out of true love.” Katsunosuke yells out his lovers name before being beheaded.

When Oharu hears of her lover’s death she attempts suicide but her mother wrestles the knife away and stops her. Lord Matsudaira from Edo is searching for a concubine and a wife to bear him a son, and after going through the whole village of Edo his messenger finally notices Oharu during singing practice and believes she would be perfect for him.

“Oharu, you redeemed yourself. All is forgotten,” Oharu’s father says when Master Matsudaira’s messenger offers the family a large amount of money to buy his daughter.

Oharu’s new husband Lord Matsudaira takes her to see Bunraku as the play that they are presented with seems to describe the life of Oharu: “Can this be real. Is it her fate. To wither. In the shade. Day and night.”

When Oharu’s duty to bear Lord Matsudaira an heir is done, Oharu is finally happy saying, “I was so unhappy, when I was first brought here. But now that I’ve given birth…I feel for the first time that this is my home.” Unfortunately for Oharu, Lord Matsudaira also falls in love with Oharu and his wife’s jealousy causes Oharu’s dismissal and her to not be allowed to see her son.

When hearing of her giving birth, Oharu’s parents arrive to Lord Matsudaira to congratulate her, only to find that out that Lord Matsudaira had dismissed Oharu sending her back home.

While Oharu had been away her father has worked up quite a bit of debt and ultimately sells his daughter to be a courtesan. After a wealthy customer arrives from Echino, Oharu is rude to him after he throws down coins for the courtesans to grasp like wild animals. Her employer is about to throw Oharu out until the wealthy customer is said to have taken a liken to Oharu. But when the wealthy customer is exposed as a fraud and a counterfeiter, Oharu is again sent home.

Oharu goes to serve the family of a woman who must conceal the fact that she is bald from her husband by wearing elaborate wigs. When one of the woman’s employers recognizes Oharu from the shimabare (red-light district) he makes crude jokes which ultimately reveal Oharu’s past. When the wife discovers that her husband knew of this, which was why Oharu was hired in the first place, she becomes jealous of Oharu and makes her chop off her hair saying, “You plan to use your beautiful hair…to steal my husband away!” The woman grabs Oharu and forcefully cuts her hair. Oharu decides to retaliate and reveal woman’s secret. (She has the family cat run with part of the woman’s fake weave.)

After being dismissed, Oharu a short time later meets and marries a fan maker. Just as it seems things are finally looking up for Oharu, the man is unfortunately killed during a robbery by an employer named Jihei .

Before again returning to her parents, Oharu attempts to become a nun and serve Buddha. One day a man who knew her comes to demand repayment for a gift of cloth she was given, and in a fury she strips off her clothing and hurls it at him. Her nudity is reflected only in the man’s eye, but the discovery of this event leads to her banishment from the temple. (She tries to explain to the nun that the man was trying to rape her, but the nun believes otherwise.)”What kind of person are you? Get out!” The nun shouts.

Oharu is thrown out into the street, and all of this time she dreams of seeing the son she gave birth to, but when this finally happens she is allowed only to get a glimpse of him sweeping past as a grand man, oblivious to her existence.

One day an elderly man (Takashi Shimura) takes Oharu in only to mock her very existence to other young male protégés saying: “Everybody take a good look. You see that? You still want to sleep with women now? You all want happiness in the next world. That’s why you’re on the Thirty-three Temple Pilgrimage. However, if you’d rather steep yourself in the impermanence of earthly life, then follow the example of this goblin cat in human form. Thank you for coming. That will be all.” Oharu furiously makes the notion of a cat as she leaves.

When Oharu hears the news that Lord Masdaira has died and her son has taken his crown she is then recalled to the Lord’s house. Thinking she can finally see her son, Oharu is instead ordered lifetime confinement within the compounds, to keep her secrets of living as a courtesan and a prostitute locked away. “If word of your vulgar behavior would get out, it would besmirch the clan’s name. You must spend day and night repenting for your sins and beseeching the spirit of our late lord for forgiveness.”

Oharu is granted a brief viewing of her son so she can grant him a farewell but must keep her distance. Oharu ends running away, choosing a life of a beggar over the life of in exile. The flashback ends and Oharu leaves the Buddhist temple as a mendicant nun, as the concluding shot follows her as she goes from house to another reciting a prayer for mercy.

Oharu is granted a brief viewing of her son so she can grant him a farewell but must keep her distance. Oharu ends running away, choosing a life of a beggar over the life of in exile. The flashback ends and Oharu leaves the Buddhist temple as a mendicant nun, as the concluding shot follows her as she goes from house to another reciting a prayer for mercy.

ANALYZE

Kenji Mizoguchi was born in Tokyo in 1898, during the Meiji period, when Japan gave up its isolationism and opened to modernization from the West; including, of course, the movies, a line of work Mizoguchi took up as a young man. Of the many films Mizoguchi directed during the 1920s and early 3o’s, little survives. In 1936 his two films Osaka and Sisters of Gion, which told the story of wronged woman in contemporary Japan were breakthroughs. By then he had developed his own unmistakable style, his ‘one scene, one shot’ theory, which avoided close-ups, reverse angels and favored a distant prolonged choreographed takes. A few years after the war, as if to confirm the opinion of critics who were calling him old-fashioned, Mizoguchi turned to classic literature for a series of films that, beginning with The Life of Oharu and continuing with Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff, would win him a top prize at Venice three years in a row and make his reputation in the west, which was then belatedly discovering the cinema of Japan. Some Japanese critics at the time objected to the liberties Mizoguchi took in adapting national classics, but that an artist can take liberties and still remain true to a tradition only attests to its vitality. As a national storyteller, Mizoguchi has few peers among filmmaker’s anywhere. The Life of Oharu was adapted by the director and his regular scriptwriter, Yoshikata Yoda, from Saikaku’s The Life of an Amorous Woman, a novel from the seventeenth century related in the first person by an unnamed woman confessing to her numerous carnal sins, and thereby implicating a whole society.

Mizoguchi’s ‘one scene, one shot’ theory is noticeable right in the beginning frame of The Life of Oharu which is at times comedic, erotic and highly engrossed in melodrama. It opens with the camera steadily following behind an aging street-walker walking in the dark outskirts of Kyoto. The woman’s name is Oharu (Kinuyo Tanaka) and we will follow her through a period of thirty years of her life. The actress Kinuyo Tanaka, appeared in 14 of Mitzoguchi’s films, and one of her strengths in The Life of Oharu is her brilliance at playing the same character throughout this period of thirty years. We watch Oharu make her way in a Buddha temple, and while looking at one of the statues of Buddha’s disciples, she will see the resemblance of her forbidden love, during her youth. The film will than flash back to several pivotal events of Oharu’s life, and like Saikuku’s novel, the protagonist will wander through various ups and downs, most of these moments will be downs; as one after another a accumulation of sorrows will add up to melodrama, fate and tragedy.

Oharu faces some major conflicts of interest as her sole role in 16th Century Japanese society, as her conflict changes while society changes with each new stage that she enters throughout the story. The first stage Oharu is in she belongs to a respectable circle who served in the imperial courts. But when Oharu willfully chooses to love a lowly page, (played by the legendary actor Toshiro Mifune) due to class difference and of breaking protocol, she will fall into disgrace and her entire family will be exiled from the city of Kyoto and never to return, while her young love is executed by beheading. When Oharu hears of her lover’s death she attempts suicide but her mother wrestles the knife away and stops her. Lord Matsudaira from Edo is searching for a concubine and a wife to bear him a son, and because of Oharu’s father never forgiven Oharu for single-handedly destroying his noble family’s honor, he sells his daughter to Lord Matsudaira. When Oharu’s duty to bear Lord Matsudaira an heir is done, Lord Matsudaira unfortunately also falls in love with Oharu, which enrages his wife with jealousy and causes Oharu’s dismissal and her to never be allowed to see her son.

While Oharu had been away her father has worked up quite a bit of debt. This leads Oharu to several occupations, one becoming a courtesan, another a maid who is serving a wealthy family of a woman who must conceal the fact that she is bald from her husband by wearing elaborate wigs. When the wife becomes jealous of Oharu and forces her to chop off all her hair, Oharu decides to retaliate and reveal the woman’s secret to her husband. After being dismissed again, Oharu for a short time later meets and marries a fan maker and is finally at a place in her life where she is happy and content. Just as it seems things are finally looking up for Oharu, the man is unfortunately killed during a robbery, and so Oharu attempts to become a nun and serve Buddha. But the discovery of an attempted rape leads to Oharu’s banishment from the temple. Ultimately the son that Oharu had bore when she was chosen for her beauty as a lord’s concubine has succeeded his father, and as the new lord he finally wants to take his old mother into his care. Once again, Oharu is ceremoniously carried in a palanquin to the lord’s manor, and things at first are looking good for her. But instead Oharu is peremptorily told that she has disgraced the clan by becoming a prostitute and instead will not be allowed to live with her son, or even be able to see him, except briefly, from afar, as she saw him once before in the street while he was a young boy and was passing by with his entourage. The sequence of her trying to get a glimpse of her son in a sunlit garden is tragic, as he and his attendants stride along a veranda, and Oharu fights off his son’s assistances trying her to get a closer view of her only child. Her story ends as it began: the hierarchy that cruelly thwarted the passionate love of her youth now thwarts the old mother’s love for her son. Oharu decides to escape the prohibitive domain and becomes a mendicant nun as the film concluding shot follows her as she goes from one house to another reciting a prayer for mercy.

Kenji Mizoguchi’s other masterpieces include The Crucified Lovers, which is about a wealthy scroll-maker who is falsely accused of having an affair with his best worker, and then their is one of my favorites, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum which tells the story of the son of a famous actor, who is openly praised for his performance on the stage just due to his name. Street of Shame is a film that tells the various stories on the lives of several prostitutes in a brothel. Ugetsu, a romantic ghost story about two men, one who wants to be a samurai, another who wants to be rich; and the tragedy that occurs for the both of them. And last but not least Sansho the Bailiff, which is considered beside Ugetsu as one of his best films and usually is cited as one of the greatest films in the world. It tells the story of a compassionate governor who is sent into exile and his wife and children try to join him, but are taking into slavery camps and suffer beatings and oppression. Sansho the Bailiff is one of my favorite films and is on my top 10 films of all time. Ugetsu is considered along with Sansho the Bailiff as being one of the greatest of all Japanese films.

During the course of her entire life, Oharu in The Life of Oharu is portrayed as having little autonomy, and made to be utterly dependent on male authorities for her social position as well as her personal happiness. Japanese forms of patriarchy are revealed as Oharu is continually objectified as the sexual and domestic property of men as well as women of higher caste, from being chosen for her perfect face and perfect body by the Lord Matsudaira’s servant, to her sole purpose as a concubine of Lord Matsudaira to produce his male heir, to being forced into prostitution by her father. Furthermore, her role in 16th Century Japanese society is greatly strained as she was originally cast aside from her role as a courtesan for choosing her own lover. It is Oharu’s original and later refusals to obey such patriarchal systems of gendered labor through making her own decisions that precipitate her descent through the class system and into depression. A good deal of the film is shot seen from a high-angle view well above eye level, which tends to diminish and objectify the subject, and Oharu increasingly comes to seem less like an autonomous character and more like a subject for study–and pity.

If you would do a poll on the greatest Japanese directors you would get Akira Kurosawa in the far lead with Yasujiro Ozu a distant second and Mizoguchi being unfortunately in the third. And yet Mizoguchi’s films are just as important, poetic and say just as much about Japanese culture than Kurosawa and Ozu, maybe more. Like the others Mizoguchi is considered one of the masters during the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, which occurred during the Allied postwar Occupation of Japan. Like Ozu and Kurosawa, Mizoguchi had his own personal themes that he relished on in each film he made such as the sudden changes in class, oppressive male figures of authority, and the female protagonist who sacrifices everything for others only to have her life ruined. Mizoguchi experienced all of these things at some level as he grew up in Tokyo as a young child, and such events such as the loss of his sister and mother through sale to a geisha house and death, respectively, as well as his father’s inability to take care of his family played a major role in deciding what kind of films Mizoguchi would come to direct. Many critics and scholars have questioned Mizoguchi as a ‘feminist’ director speculating that the director harbored feelings of guilt with regard to women and sought their forgiveness, as most of his films focused on poverty, greed, morality, redemption and a woman’s place in Japanese society. The Occupation and its devastating after-effects also played a role in his later films, revealed through theme or direct content, such as in his last film, Street of Shame which related the period’s sexual violence, proliferating military brothels, and increased poverty, as this particular film was made during the last years of the Occupation. The Life of Oharu sounds like a simple lurid melodrama, but the director brilliantly avoids taking advantage of the sensational aspects of Oharu’s life. Instead the events are expressed as a tragic memory of fate as Mitzoguchi’s gorgeous use of period locations, costumes and culturistic rituals makes Oharu’s experiences more like enactments. Film Critic Roger Ebert added The Life of Oharu to his ‘Great Movies and states: “A great deal of the story’s pathos comes from the fact that no one except Oharu knows the whole of her life history; she is judged from the outside as an immoral and despicable women, and we realize this is no more than the role society has cast her in, and forces her to play.” Mizoguchi makes no attempt to portray any of the male character’s as completely despicable, or an out-right villain. All of the men within the structure of its story are simply behaving within the boundaries that were created for them, and of the traditions and stereotypes that were created by their society. In one of the powerful and heartbreaking sequences I have ever witnessed an elderly man (surprisingly played by actor Takashi Shimura) takes Oharu in at her lowest point, only to mock her very existence to other young male protégés saying such cruel things as: “Everybody take a good look. You see that? You still want to sleep with women now? You all want happiness in the next world. That’s why you’re on the Thirty-three Temple Pilgrimage. However, if you’d rather steep yourself in the impermanence of earthly life, then follow the example of this goblin cat in human form. Thank you for coming. That will be all.” Oharu furiously and pathetically makes the notion of a cat before leaving, while everyone laughs at her; as this sequence will literally tear your heart out. It is unclear what Mizoguchi’s personal opinions were on male hierarchy and of Japanese society during this period in history, but the story of Oharu’s downfall is quite possibly one of the saddest stories on a women I have ever seen presented in the cinema.

If you would do a poll on the greatest Japanese directors you would get Akira Kurosawa in the far lead with Yasujiro Ozu a distant second and Mizoguchi being unfortunately in the third. And yet Mizoguchi’s films are just as important, poetic and say just as much about Japanese culture than Kurosawa and Ozu, maybe more. Like the others Mizoguchi is considered one of the masters during the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, which occurred during the Allied postwar Occupation of Japan. Like Ozu and Kurosawa, Mizoguchi had his own personal themes that he relished on in each film he made such as the sudden changes in class, oppressive male figures of authority, and the female protagonist who sacrifices everything for others only to have her life ruined. Mizoguchi experienced all of these things at some level as he grew up in Tokyo as a young child, and such events such as the loss of his sister and mother through sale to a geisha house and death, respectively, as well as his father’s inability to take care of his family played a major role in deciding what kind of films Mizoguchi would come to direct. Many critics and scholars have questioned Mizoguchi as a ‘feminist’ director speculating that the director harbored feelings of guilt with regard to women and sought their forgiveness, as most of his films focused on poverty, greed, morality, redemption and a woman’s place in Japanese society. The Occupation and its devastating after-effects also played a role in his later films, revealed through theme or direct content, such as in his last film, Street of Shame which related the period’s sexual violence, proliferating military brothels, and increased poverty, as this particular film was made during the last years of the Occupation. The Life of Oharu sounds like a simple lurid melodrama, but the director brilliantly avoids taking advantage of the sensational aspects of Oharu’s life. Instead the events are expressed as a tragic memory of fate as Mitzoguchi’s gorgeous use of period locations, costumes and culturistic rituals makes Oharu’s experiences more like enactments. Film Critic Roger Ebert added The Life of Oharu to his ‘Great Movies and states: “A great deal of the story’s pathos comes from the fact that no one except Oharu knows the whole of her life history; she is judged from the outside as an immoral and despicable women, and we realize this is no more than the role society has cast her in, and forces her to play.” Mizoguchi makes no attempt to portray any of the male character’s as completely despicable, or an out-right villain. All of the men within the structure of its story are simply behaving within the boundaries that were created for them, and of the traditions and stereotypes that were created by their society. In one of the powerful and heartbreaking sequences I have ever witnessed an elderly man (surprisingly played by actor Takashi Shimura) takes Oharu in at her lowest point, only to mock her very existence to other young male protégés saying such cruel things as: “Everybody take a good look. You see that? You still want to sleep with women now? You all want happiness in the next world. That’s why you’re on the Thirty-three Temple Pilgrimage. However, if you’d rather steep yourself in the impermanence of earthly life, then follow the example of this goblin cat in human form. Thank you for coming. That will be all.” Oharu furiously and pathetically makes the notion of a cat before leaving, while everyone laughs at her; as this sequence will literally tear your heart out. It is unclear what Mizoguchi’s personal opinions were on male hierarchy and of Japanese society during this period in history, but the story of Oharu’s downfall is quite possibly one of the saddest stories on a women I have ever seen presented in the cinema.