Ikiru (1952)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Ikiru Akira Kurosawa” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Sometimes I think of my death. I think of ceasing to be…and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.”

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Ikiru Akira Kurosawa” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Sometimes I think of my death. I think of ceasing to be…and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.”

-Akira Kurosawa

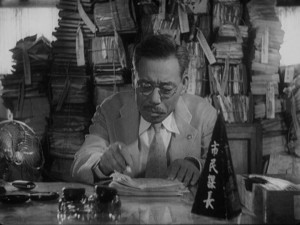

Everyday he sits at his desk with stacks of countless documents, and takes a rubber stamp and presses on each one of those documents over and over again. He’s the Public Affairs Section Chief in City Hall, and his job is to deal with citizen complaints, and yet nothing is ever decided, and instead those complains are simply passed over to other departments. His name is Kanji Watanabe, a middle-aged man who has worked in the same boring bureaucratic position for thirty years, has never missed a day, doing the same work repeatedly not really accomplishing anything. His wife is dead and his son and daughter-in-law live with him in hopes in receiving his retirement pension. Watanabe doesn’t know yet that he has a fatal form of stomach cancer and when he discovers this, he will realize he has less than six months to live. Ikiru is director Akira Kurosawa’s spiritual and life-affirming masterpiece and is one of the most powerful films in the world. Ikiru tells the simple story of a man who knows he is going to die, and yet he finally sees the importance he can bring to himself and other people. Ikiru in Japanese means “To Live” and that’s exactly what this film is about. Takashi Shimura who plays this frail defeated old man has played in several of Kurosawa’s films, most famously as the fearless leader of the seven warriors in his classic epic The Seven Samurai. In Ikiru he plays the exact opposite, an everyman bureaucrat who has lived a life by not really living. He is nicknamed “the Mummy” at work because his character is lifeless, just drifting through life and not really experiencing it. When discovering that he has less then six months to live, he descents into a form of despair and defeat, which will lead him through a series of stages, before arriving to the realization of his own importance which will involve the overcoming of the inertia of bureaucracy, to help the less fortunate.[fsbProduct product_id=’777′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Film professor Richard Brown states, “Ikiru is a cinematic expression of modern existentialist thought. What it says in starkly lucid terms is that ‘life’ is meaningless when everything is said and done; at the same time one man’s life can acquire meaning when he undertakes to perform some task that ‘to him’ is meaningful. What everyone else thinks about that man’s life is utterly beside the point, even ludicrous. The meaning of his life is what he commits the meaning of his life to be. There is nothing else.” In one of the greatest scenes of the film Watanabe asks a complete stranger to help him spend his money on ‘having a good time’, because he doesn’t know how to spend it. The stranger takes him out on the town, to gambling parlors, dance halls and the red light district, and finally to a bar where the piano player calls for requests and Watanabe, still wearing his overcoat and hat, asks for the song ‘Life Is Short Fall in Love, Dear Maiden.’ The piano man says, “Oh, yeah, one of those old ’20s songs,” but when he plays it, Watanabe starts to softly sing to the song, barely moving his lips, and suddenly the bar becomes silent. For just a brief moment, these young drunken men and women are drawn into a deep existential contemplation on just how short and precious their lives really are.

PLOT/NOTES

The very first shot of Ikiru is a X-ray of Watanabe’s chest as a narrator begins the film: “At this point, our protagonist has no idea he has cancer. But it would only be tiresome to meet him now. After all, he’s simply passing time without actually living his life.” The film then goes to city hall as a group of women come in with a complaint, protesting against a pool of mosquito-infested sewage in their neighborhood that’s giving some of their children an awful rash.

Some of the women say, “Can you do something? It would make a great playground if you filled it in.” When an employee takes the complaint to Watanabe who is the Public Affair’s Section Chief he just say’s, “Engineering Section” because he doesn’t really want to deal with the problem, and if he tried it would only bring strain and annoyance on other departments. The unknown narrator starts again by saying, “Ah, here is our protagonist now. But it would only be tiresome to meet him now. After all, he’s simply passing time without actually living his life. In other words, he’s not really even alive.” ‘

During one of his regular work days one of Watanabe’s subordinates laughs at a joke she read during work. When asked to read the joke out loud to everyone, she reads, “I heard you’ve never even taken a vacation. Is that because City Hall couldn’t function without you? No. Because everyone would realize that City Hall doesn’t need me at all.” No one laughs at the joke as the subordinate awkwardly sits back down to work.

The narrator begins again by saying, “Oh, this will never do. He might as well be a corpse. In fact this man has been dead for more than 20 years now. Before that, he did live a little. He even actually tried to do real work. But now, there’s barely a trace of his old passion and ambition. He’s been worn down completely by the minutia of the bureaucratic machine and the meaningless busyness it breeds. Busy always very busy. But in fact, this man does absolutely nothing at all. Other than protecting his own spot. The best way to protect your place in this world is to do nothing at all. Is this really what life is about? Before our friend will take this question seriously, his stomach has to get a lot worse, and he’ll have to waste much, much more time.”

The next day the complaint and proposal for creating a park that was brought in earlier by several women gets taken around to different departments. There is an interesting montage where it shows a series of women being transferred from one office to another with the proposal to eventually come back to where they originally started from in a full circle. “How dare you? Stop giving us the runaround! What a mockery of democracy!” One of the women yells.

Unfortunately for the employees the Section Chief Watanabe has taking the day off. A lot of the employees are curious since Watanabe has never taking a day off because nothing moves unless he stamps it. One of the employees says, “One more month and he’d have broken the record of 30 years without a single absence.” Some of the employees are happy to have him gone with some of them hoping to replace him as soon as he is out as they all gossip on who would be next in line to replace him.

The next scene shows Watanabe leaving the X-Ray Lab as he waits out in the waiting room. While waiting, Watanabe talks to another patient who asks him if there is anything wrong with his stomach. The patient tells Watanabe that one of the men in the waiting room has stomach cancer, because the doctor told him he had an ulcer. The patient tells Watanabe, “And stomach cancer is practically a death sentence. The doc usually says, it’s just a mild ulcer, and that there’s no real need to operate. And that you can eat whatever you want as long as it’s easy to digest. If that’s what he tells you, you’ve got a year, at most.” When the patient starts describing the symptoms you see a sudden fear in Watanabe’s eyes because he is describing the symptoms he is feeling.

When Watanabe is called into the doctor’s office the doctor says that he has a mild ulcer and Watanabe knows the doctor is lying and his expression is a sadness that’s beyond words. Watanabe begs the doctor to admit it’s stomach cancer but he won’t. After Watanabe leaves one of the nurses asks the doctor if Watanabe has a year and the doctor says, “No, I’d give him six months. What would you do if you had only six months left to live, like him?”

After learning he has stomach cancer and less than a year to live, Watanabe quietly walks home in complete silence (the sound is muted) but the silence is broke when he almost walks onto oncoming traffic.

Back at his home Watanabe’s son Mitsuo and his wife come home wondering why the house is completely dark. They both rudely talk about their father’s retirement bonus and his pension not knowing their father is listening to their conversation as he is sitting in the dark. When they find their father sitting in the dark they ask him what is wrong but Watanabe says nothing.

There is a powerful moment when Watanabe looks at a picture of his dead wife as it then flashes back to her funeral when his son Mitsuo was only a young boy. It then flashes back to Mitsuo growing up and Watanabe going to his baseball games; Mitsuo having surgery to get his appendix removed and leaving and joining the military; showing how Watanabe raised his son up on his own. While Watanabe is thinking back to all his memories he keeps repeating his son’s name, “Mitsuo, Mitsuo…” This scene makes you realize how him and his son have grown apart over the last few years.

One of the saddest scenes in the film is Watanabe going to bed and crying himself to sleep under the covers while the camera pans up to a commendation he was awarded after 30 years at his post as Public Affairs Section Chief.

Watanabe doesn’t show up or call for work for five days as an employee is sent to his home to ask where he is. The maid eventually tells Mitsuo’s wife and she call’s Mitsuo at work to let him know his father hasn’t been to work in five days.

Descending into a small dead-end bar Watanabe tries to come in terms with his upcoming death, mourning in defeat and despair. He meets a man there who is an aspiring writer and reveals to him that he just found out he has stomach cancer. The stranger then says, “it’s suicide to drink if you have stomach cancer. It’s seems you’re carrying a heavy load indeed.” Watanabe sadly says how furious he is with himself. He says, “I’d never even bought a drink with my own money. It’s only now that I don’t know how much longer I’ve got to live.” The stranger says he understands but to drink is plain crazy. Watanabe answers “Drinking this expensive sake is like paying myself back with poison for the way I lived all these years.” Watanabe then says to the stranger, “I have 50,000 yen here with me, which I’d like to spend all at once. But embarrassingly enough, I don’t even actually know how.”

The stranger tells him “I understand. But please put your money away. Tonight’s on me. Just leave things to me. Truly fascinating, I realize it’s rude to call you fascinating, but you’re an extremely rare individual. I’m a half-baked fool who writes meaningless novels. You’ve really made me think tonight. Your cancer has opened my eyes to your own life. We humans are so careless. We only realize how beautiful life is when we chance upon death. But few of us are actually able to face death. You were a slave to your own life. Now you will become its master. I’m telling you, it’s our human duty to enjoy life. Wasting it you desecrate God’s great gift. We’ve got to be greedy about living. We learned that greed is a vice, but that’s old. Greed is a virtue. Let’s go. Let us go reclaim the life you have wasted. Tonight it will be my pleasure to act as your Mephistopheles.”

The stranger takes Watanabe on a wild night on the town. Buying him a new white hat to celebrate his new life, they both go to gambling parlors, numerous bars, dance clubs, and the red light district and get totally obliviated. When at a dance club watching a striptease the stranger tells Watanabe while intoxicated, “Striptease. Now, this is what I call art. No…it’s more than art. It’s more direct. In other words that female body gently undulating up there on stage is a juicy steak, a glass of liquor, a bottle of camphor, streptomycin, uranium…”

One of the most touching scenes of the film is when their at a dance hall around several women and the piano player asks for song requests and Watanabe requests ‘Life Is Brief.’ “Oh, that love song from back in the nineteen teens,” the piano man says; but plays it anyways. Once he starts to play, Watanabe, hardly moving his lips quietly starts to sing along with great sadness and suddenly the bar becomes silent. All the drunken men and party girls listen to him sing and for a brief moment they realize how short and precious their young lives really are.

The following day, Watanabe runs into one of his former female subordinates who hardly recognized him in his new white hat. She tells him she recently quit because she couldn’t bare the boredom and repetitiveness of the job no longer and was looking for his home because she needs his approval to quit the civil service. She says, “It’s killing me. Each day is predictable as the last. Nothing new ever happens. Still, I put up with it for a year and a half.” Watanabe is attracted to her love of life and great enthusiasm and fun. His son Mitsuo and daughter in law are wondering why their father has been acting so strangely lately and not been showing up to work for the past five days. When they see him bring home his former subordinate they find the situation awkward and believe that their father is having a relationship with this much younger woman.

When Watanabe takes his young subordinate into his room to approve her paperwork, she reads his commendation award and says, “thirty years in that awful place. It kills me to think of it.” Watanabe tells her that every time he sees that award he remembers the joke she read out to everyone. He says to her,”No, no, that joke hit the nail on the head. No matter how hard I try, I can’t remember a thing I’ve done in that office over the last thirty years. What I mean is…I was just busy and even then I was bored.” Before she leaves he offers to leave with her and because of him earlier noticing her stockings she was wearing are very worn; he offers to take her shopping. She is very grateful for his gift and afterwards tells him, “I’m all dizzy! To buy them myself, I’d have to live on sardines for lunch for three months.”

After shopping together they have lunch at a small restaurant and she tells him all the nicknames that she gave all the bosses at the job and Watanabe starts laughing. When she says she had a nickname for him too she says, “But I’m not going to tell, ’cause I had you all wrong.” But he really wants her to tell him and when she tells him she nicknamed him ‘The Mummy,’ you can see in Watanabe’s eyes that he understands why he was called that.

Watanabe begs her to spend the rest of the day with him as they go play the slots, and then he takes her ice-skating and to the movies (while he dozes off during the picture) and then back to his home for dinner. During dinner Watanabe says, “I had a truly marvelous day today.” She says how he was snoring throughout the movie. He then tells her that his son doesn’t seem to care about the sacrifices he made for him over the years at his job and that’s why he became a mummy. She then says to him, “you can’t blame it all on your son. Not unless he asked you to make a mummy of yourself. Parents are all the same. My mom gives me the same kind of line sometimes. ‘The things I suffered for you.’ And I’m grateful she had me. But it’s not my fault I was born. What’s the matter with you… bad-mouthing your son to me?”

Later that evening Watanabe decides to try to reach out to his son and finally tell him about his cancer but before he can get a word in his son lashes out saying, “Father, we respect your right to freedom of expression, but how dare you bring a young woman like that home. And holding hands with her in your room. I could hardly face the maid.” Watanabe is speechless at his sons accusations and quietly heads to his room without saying another word.

The narrator of the film starts to say once again: “It’s been two weeks now since our protagonist abandoned his spot. During that time various rumors and speculations have swirled around our Watanabe.” The stacks of paperwork on Watanabe’s desk begins to build up since Watanabe hasn’t been to work.

Watanabe’s former subordinate eventually starts questioning Watanabe’s motives when he keeps asking her out again. When Watanabe arrives at her job, he has her reluctantly accept. When out to eat at a restaurant she starts asking him why he wants to always see her; because of their huge difference in age. She says, “I feel badly that you keep treating me, but I’ve had it up to here. Let’s stop doing this. It doesn’t feel right.” It’s hard for Watanabe to get out in words what he wants to say to her but eventually he does, finally telling her everything:

“You see, I’m going to die soon. I’ve got stomach cancer. It’s right here. Can you understand? No matter what I do, I’ve only got six months or a year left. Ever since I’ve known that, the way I feel about you became like…I nearly drowned in a pond once when I was a child. I felt exactly the same way then. Everything seems black. No matter how I struggle and panic, there’s nothing to grab hold of, except you.

“And your son?”

“Don’t talk to me about my son. I have no son. I’m all alone. My son is somewhere far, far, away. Just as my parents were when I was drowning in that pond. It hurts me even to think about him now.”

“But why is anyone like me…so?”

“It’s just that, that, you’re, I mean…when I look at you right here, this old…this old mummy…In other words, you’re like, you seem like my family…No, that’s not right. You’re young and you’re healthy, so that’s why…No, that’s not right. In other words, why are you so incredibly alive? That’s why I’m envious. This old mummy envies you. Before I die, I want to live just one day like you do. Until I’ve done it, I can’t just give up and die. In other words…I just want to do something. But it’s just that, I don’t know what. But you do know.”

She then tells him he can make his life worth living too, he just needs to find something that makes him truly happy. She reveals that her happiness comes from her new job making toys, saying, “making them, I feel like I’m playing with every baby in Japan. Why don’t you try making something too?” Watanabe asks, “What can I possibly make at that office?” She agrees and says the best film for him to do is quit. Suddenly that gives Watanabe an idea and his eyes widen and he says, “I know I can do something there. I just have to find the will.”

He quickly rushes out of the restaurant which at the same time girls in the other room sing ‘Happy Birthday to a friend which in a way are also singing for Watanabe and his new rebirth.

That very next day at work one of Watanabe’s associates right below him is walking into work and tells another employee, “it’s a matter of time before he resigns. His son came yesterday about his pension, which means I’ll finally be section chief.” Suddenly his associate notices Watanabe back at work and sitting in his desk, which is unfortunate for him. Watanabe is now a new man and decides to dedicate his remaining time to accomplishing one worthwhile achievement before his life comes to an end as all his associates watch him pull out piles of old papers.

The group of women in the beginning of the film that were shuttled from one office to another, protesting against a pool of stagnant water in their neighborhood now interests Watanabe and he becomes personally involved in the situation, instead of usually just ignoring it.

When his associates say it is something for engineering; Watanabe says, “No, this is just the sort of matter that Public Affairs must take the lead on. This isn’t just Engineering’s problem. Parks and Sewage also have a responsiblity.” When he gets out of his seat and tells his associates he’s going out to personally survey the site, he tells them to get a report ready. When they tell him that’s a little impossible; Watanabe says, “Not if you put your mind to it.”

He then takes the case from one bureaucrat to another, with complete determination to see that a children’s park is built on that wasteland. He battles with many of the Section Chiefs in these departments and seeing his unrelenting determination in the project; they eventually “OK” his creation of the park. All these tedious meetings back and forth with administration is upsetting Watanabe’s associate. “We been at this for two weeks, at least they could tell us whether or not the funds are there. Administrations just cruel. Doesn’t it make you furious when they walk all over you this way?” Watanabe just calmly replies, “No. I can’t afford to hate people. I don’t have that kind of time.” With all his hard work Watanabe is able to overcome the inertia of bureaucracy and turn a mosquito-infested cesspool into a children’s playground.

The scenes of his efforts in creating the playground do not come in chronological order, but as flashbacks from his funeral service at the last 40 minutes of the film. One of my favorite scenes in the film is where he gets threatened by a mob of men who want to use that sewage space for a business restaurant and tell him to shut his trap. They than threaten him by grabbing him by the coat.”Just shut up and back down. You’re risking your life.” Watanabe when hearing this slowly smiles, knowing they can’t hurt him anymore than whats enviably going to happen to him naturally.

The last third of the film takes place during Watanabe’s wake, as his former co-workers try to figure out what caused such a dramatic change in his behavior. His transformation from lifeless bureaucrat to passionate advocate puzzles them and makes them wonder. The new Section Chief that replaced Watanabe seems to be taking all the credit of the park that Watanabe created and never mentioned his name in a speech that he gave in the opening ceremony of the park. When the press and newspapers arrive to the wake they question his honesty because much of the community has come forward saying the building of the park was Watanabe’s plan and that he had kept the construction of it alive.

Since Watanabe was found frozen to death in the park that he created the press are saying that he committed an act of protest against city officials who were against the creation of the park. The women of Kuroe where the park was created come to give their respects to Watanabe. When they walk in they all start mourning over the death of Watanabe; and while they are mourning you see Mitsuo look over at his wife; probably shocked at what their father had accomplished for many of the residents in the town.

Watanabe’s family and associates all gather to remember him over the next few hours, drinking too much and drunkenly arguing and speaking the truth. And during the wake his co-workers start to speak out on how Watanabe was the real man who was behind the creation of the park.

Near the end of Watanabe’s wake a park officer comes in delivering Watanabe’s white hat (which symbolized Watanabe’s new-rebirth of life) that he found in the park and describes to everyone what he saw the night in the park when Watanabe died. He says, “last night, I was on patrol in the new park when I met him. It was nearly 11:00. He was on the swing and what with all that snow. I just assumed he was some drunk. But he seemed to be perfectly happy. He poured his whole heart into that song of his. His haunting voice…pierced the very depths of my soul…”

In an iconic scene from the film in the last few moments in Watanabe’s life, you see Watanabe sitting on the swing of the park that he had created. As the snow falls, we see Watanabe gazing lovingly over the playground, at peace with himself and the world and finally knowing he can die a happy man. He starts singing ‘Life is Brief’ again and this sequence is one of the most magical and emotional scenes ever in cinema history.

During his fathers wake Mitsuo finds an envelope with his name on it along with his father’s bankbook and forms for expediting his retirement bonus. Mitsuo and his wife now realize their father knew he was dying all along; especially when that young girl that they thought was his lover never did show up to his funeral. When all the co-workers hear the police officers story everyone realizes that Watanabe must have known he was dying of stomach cancer and they all decide to start living their lives with the same dedication and passion as Watanabe did from that day forward.

But unfortunately when back to work the next week they go right back from where they started as mindless drones, passing their problems off to other departments and not going out of their way to accomplish anything.

ANALYZE

“Sometimes I think of my death,” Kurosawa has written: “I think of ceasing to be . . . and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.” The story of a man who knows he is going to die, the film is a search for affirmation. The affirmation is found in the moral message of the film, which, in turn, is contained in the title: Ikiru is the intransitive verb meaning “to live.” This is the affirmation: existence is enough. But the art of simple existence is one of the most difficult to master. When one lives, one must live entirely––and that is the lesson learned by Kanji Watanabe, the petty official whose life and death give the meaning to the film.

“Sometimes I think of my death,” Kurosawa has written: “I think of ceasing to be . . . and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.” The story of a man who knows he is going to die, the film is a search for affirmation. The affirmation is found in the moral message of the film, which, in turn, is contained in the title: Ikiru is the intransitive verb meaning “to live.” This is the affirmation: existence is enough. But the art of simple existence is one of the most difficult to master. When one lives, one must live entirely––and that is the lesson learned by Kanji Watanabe, the petty official whose life and death give the meaning to the film.

As with The Drunken Angel and High and Low, Kurosawa chose to break Ikiru in half. In the 1948 film, the reason was that he was tracing a parallel between doctor and gangster; in the 1963 picture, he was concerned with practice and theory (and illusion and reality) on a very large scale. In Ikiru it is important that the second half becomes posthumous, because much of the irony of the film results from a (wrong) assessment of Watanabe’s actions made by others after his death. Or, to put it another way, we have seen what is real—Watanabe and his reactions to his approaching death. In the second half, we see illusion—the reactions of others, their excuses, their accidental stumblings on the truth, their final rejection of both the truth and of Watanabe.

Perhaps for this reason Kurosawa insists so much upon the “reality” of the first half, and uses all cinematic techniques to make certain that we become absolutely convinced of this reality. Not that he insists upon the literal, far from it. He, along with the writer whom Watanabe meets, knows that “art is not direct.” Rather he uses a variety of styles (expressionistic, impressionistic, etc.) in conjunction with almost all of the techniques of which the camera is capable.

The picture begins with plain lettering, white on black (a bit like that of Citizen Kane, which this film in more than one way resembles but which Kurosawa had not yet seen) and under it is what becomes the main musical theme of the film. It is a fugue or, to be more precise, a ricercare. Whether this (ricercare means to search for again, to hunt for, or to follow) was intentional or not, it was certainly a happy thought because this, after all, is what the film is about. The first scene is a close-up of an x-ray. We are thus shown Watanabe’s inside before we are shown his outside, and we are shown the cancer (literally) as defining the man. In the same way, throughout the first half of the film, we are shown his body and what he does; in the second half the body has disappeared and we are shown––through the conversation of others—his soul, what remains of him.

Like Sartre’s Roquent, like Camus’ “foreigner” (who also knows he is going to die), like Kafka’s Gregor and Doestoevsky’s Prince Myushkin, Watanabe discovers what it means to exist, to be—and the pain is so exquisite that it drives him, it inspires him. He conceives the plan that will save him, though in the simplest of terms it is a form of insurance against having “lived in vain.” He rescues the petition from certain oblivion and turns wasteland into a park. He has flung himself onto this one thing that will keep him afloat. He forces the park into being.

The meaning is that Watanabe has discovered himself through doing. Perhaps without even grasping the profound truth he was acting out, he behaved as though he believed that it is action alone that matters; that a man is not his thoughts, nor his wishes, nor his intentions, but is simply what he does. Watanabe discovered a way to be responsible for others, he found a way to vindicate his death and, more important, his life. He found out what it means to live.

The office-workers (at least when drunk at the wake) seem to believe this. They are loud in their sobs of repentance and their praise of the dead (this wake is not in the slightest overdone—Japanese wakes are always like this: drunk, full of back-biting toward the deceased, to end in an orgy of praise and fellow-feeling around dawn) but––sober––they have forgotten their moment of truth. Only one—the one who first spoke up for Watanabe at the wake—remembers. He is reprimanded. He sits down, and Kurosawa has so placed the camera that he disappears behind his piles of papers as though he were being buried alive. He has—in his way—become Watanabe. And the final scene also suggests this. This clerk is on his way home. It is evening. Below the bridge where he stands is the park that Watanabe made. He stops and looks at the sunset just as Watanabe has in an earlier scene when he stopped, at the same place, looked, and said: “Oh, how lovely––I haven’t seen a sunset for thirty years.” It is as though this single clerk might remember Watanabe’s lesson—a man is what he does.

On the other hand, it is quite possible that Kurosawa would disagree with this interpretation of his picture. He certainly did not think of himself as an existentialist. Still, throughout his films there runs a moral assumption that has much in common with the existential thesis. The same thing occurs in Dostoevsky, a disaffiliate whom the existentialists have claimed, and it is telling that the Russian author should be the director’s favorite.

Of course, one of the fine things about Ikiru is that, like other great films, it is a moral document and part of its greatness lies in the various ways in which it may be interpreted. Here, as in the novels of Dostoevsky, we see layer after layer peeled away until man stands alone––though what the layers mean and what the standing man means may vary with the interpretation. Personally (as I have indicated) I think it means that man is alone, responsible for himself, and responsible to the choice that forever renews itself. This interpretation has never been better put than by Richard Brown, when he wrote:

“Ikiru is a cinematic expression of modern existentialist thought. It consists of a restrained affirmation within the context of a giant negation. What it says in starkly lucid terms is that ‘life’ is meaningless when everything is said and done; at the same time one man’s life can acquire meaning when he undertakes to perform some task that to him is meaningful. What everyone else thinks about that man’s life is utterly beside the point, even ludicrous. The meaning of his life is what he commits the meaning of his life to be. There is nothing else.”

-Donald Richie

In the movies as in life, love and death hold sway, exerting an irresistible attraction on our imagination. Love usually dominates in cinema; we sit entranced for hours as affairs of the heart wax and wane. Death seldom holds the field for so long, but erupts in spectacular finales or provocative opening scenes, functioning as punctuation or plot resolution, hardly ever insisting that we confront our own mortality. Serious films about death are rare, success in this genre even rarer.

Kurosawa challenges this tradition immediately. Ikiru’s first image is an x-ray; a voice reveals the diagnosis is cancer. Kenji Watanabe, we soon learn, has six months to live. Ikiru encompasses these six months; by facing this death Kurosawa fashions an affirmation of life, characteristically clear-headed in its exploration of man’s fate.

Of the origin of Ikiru, Kurosawa has said, “Occasionally I think of my death . . . then I think, how could I ever bear to take a final breath; while living a life like this, how could I leave it?”

But the task for Watanabe, played by Takashi Shimura with almost painful intensity, seems just the opposite of this. Not how to bear leaving a vibrant life, but how to charge empty existence with significance enough that leaving matters. For Watanabe, we are told, has been dead for twenty-five years, buried in a pattern of meaningless routine. We meet him at his desk in City Hall, stamping documents that exist only to be stamped, surrounded by subordinates who will soon be as moribund as he.

Kurosawa affirms the futility of such a life when some women come to request that a playground be built. Shunted heedlessly from office to office, they end where they began, angry and defeated. Sixteen wipes, probably more than one could find in the whole of western cinema in the preceding decade, give point and intensity, rhythm and dynamism to this indictment of Japanese bureaucracy.

At this point Watanabe learns of his death sentence and Ikiru’s unrelenting focus on death becomes a search for meaning in life, presented in two uneven halves. In the first the bustle and energy of contemporary Tokyo provide the setting for Watanabe’s stunned acceptance of his fate, evoking a struggle to awaken to life before he loses it. The second, five months later at Watanabe’s wake, offers a retrospective view of this awakening and its failure to change the life of his colleagues.

Watanabe’s search, accentuated by movement, noise, a flow of people and places, reaches its cinematic peak in the Faustian night-town sequence. Unable to talk to his family, Watanabe confides his despair to a writer encountered in a bar. Though the most serious talk of life and death in the film occurs here, the result is a descent into hell. The writer calls himself Mephistopheles, “but a virtuous one who won’t demand payment”—an ironic virtue, indeed, since the payment, Watanabe’s death, has already been exacted. In response to despair, Mephistopheles offers pleasure, wine, women and song. They plunge into the Tokyo night of surging crowds, blaring western music, glittering reflective surfaces, with Watanabe forever a small knot of bewildered pain in this teeming sea of pleasure. His one instance of solace, the one genuine moment for him, comes as he stolidly sings an old love song, “Life is so short/Fall in love, dear maiden” rather to the horror of those surrounding him. Brilliant and dreadful, this night-town scene perhaps begins Watanabe’s awakening; he learns something: pleasure is not life.

Next, more modestly, he clings to a young former colleague who offers something more comforting than pleasure, human companionship, then finally, the spark that rekindles life, a toy rabbit. Watanabe clutches it and starts down the stairs, his rebirth bright on the soundtrack in the voices from across the room singing “Happy Birthday,” heard through the next scene as, back in his office, Watanabe searches out the petition for a playground and hurries out into the rain—committed to action, free of despair.

Cut to a picture of Watanabe on his funeral altar as the narrator says, “Five months later our hero died.” A new style, static and visually spare, fits this ceremonial gathering of family, colleagues and superiors, in formal dress and formally arranged, but growing progressively more drunk and disorganized as they discuss Watanabe with varying degrees of hypocrisy, misunderstanding and, rarely, sympathy, with the most profound and sincere grief expressed in a brief interruption by women of the playground. Through this long scene in which every word and gesture is significant, a series of flashbacks—without ever showing the crucial moments or decisions—reveal the true story of the playground, ending with one of the most poignant images in cinema: Watanabe in the softly falling snow, swinging slowly in the children’s playground, singing to himself, “Life is so short/Fall in love, dear maiden”—now no mere moment of solace but the inner voice of a life regained and so, worth losing.

Kurosawa’s stature in the West stems primarily from our response to his samurai films, from Rashomon to Ran, filled by exotic characters with familiar emotions, action and conflict and dazzling passages of masterful cinematic creation. By contrast Ikiru is quiet and contemplative, and surely less entertaining. Yet critics both East and West have called it Kurosawa’s greatest achievement—attributing to this one lonely death more weight than that of forty bandits killed with such bravado in Seven Samurai. I am not sure that I agree, but why should an artist be limited to one masterpiece?

-Alexander Sesonske

It isn’t exactly clear or specific who Watanabe touched personally with his actions besides for one of the clerks at his office, who stops below the bridge where Watanabe once stopped and says, “Oh, how lovely…I haven’t seen a sunset for thirty years.” Watanabe effected this young clerk and made him look at the world much differently and realize how precious life is; and how it’s never too late to change. Watanabe’s son Mitsuo and daughter in law probably think differently of their father now; realizing why his behavior was so strange and erratic during the last few months of his life. They probably realized how wrong they were on rudely accusing him of having a relationship with a younger women; especially when they didn’t see her attend his funeral. His former subordinate will always remember Watanabe and the fun times they had together those short few days. She will always know that she was a huge inspiration for him on not only how to be alive and to appreciate life, but of his discovery on a driven purpose and motivation that can make an individual happy.

The last 40 minutes that involve Watanabe’s wake is probably the most experimental and most unusual artistic choices that Kurosawa decided upon when making the film. To eliminate the main character in the last 40 minutes of the story, a character that the audience have stuck beside through the first two hours of the film, is greatly courageous, and highly risky. The wake sequence is brilliantly crafted because Kurosawa has the audience look at Watanabe’s motivations and decisions through eyes of his friends, family and co-worker’s who didn’t have the same perspective that the audience had throughout the first two-hours of the film. Because of doing this, Kurosawa has the audience witness one man’s achievements and motivations and how it can inspire, confuse, anger, and frustrate those who look at it from the outside looking in.

Like High and Low and The Drunken Angel, Kurosawa chose to break Ikiru in two halves. In Ikiru, the second half shows Watanabe’s actions and the results of his actions after his demise. We also see the reaction of everyone else and their thoughts, excuses and projections of the truth on why Watanabe acted the way he did. The first scene of the film shows a close-up x-ray of Watanabe’s fatal cancer and the conclusion of the film has people discussing his soul and what remains of him as a human being.

Akira Kurosawa is considered one of the greatest director’s in the world. He has created so many masterpieces of film along the likes of other masters like Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Stanley Kubrick, Ingmar Bergman, Billy Wilder, Luis Bunuel, Orson Welles, Jean Renoir and Alfred Hitchcock that it’s nearly impossible to pick a favorite of his. Akira Kurosawa is mostly known for his samurai films which became very popular here in the west, which was because of his love of John Ford westerns growing up as a young boy. Kurosawa once wrote in his memoirs, “there is one person, I feel, I would like to resemble as I grow old: The late American film director John Ford.” When he created his groundbreaking masterpiece The Seven Samurai which told a story on about a bunch of farmers being attacked by bandits and who decide to hire seven different samurai’s to protect them; it not only now is considered one of the greatest films ever made but it broke new ground when it came to action adventure films and created a genre of its own about a group of men getting together to complete a mission and destroy an enemy.

He then created another masterpiece called Rashomon which was unique and groundbreaking in its story structure because it not only told a story through several different perspectives of its character’s, but it also questioned the authenticity of its different point of views. Kurosawa’s other samurai films like Throne of Blood, Kagemusha, Yojimbo and The Hidden Fortress were taken on the stories of William Shakespeare and were also very influential for director’s like Sergio Leone and George Lucas who had gotten many of their story ideas from many of Kurosawa’s films. Kurosawa also created films outside the samurai genre like the noir crime film The Drunken Angel and The Bad Sleep Well which was based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. He also created one of the greatest police procedural thriller’s with High and Low, about a rich businessman who is being terrorized by a kidnapper. Red Beard was a film about a town doctor who trains a young intern at a local hospital in 19th century Japan and Kurosawa’s most underrated film was Dersu Uzala which told a story about a Russian explorer who befriends a local hunter throughout several years of his life. When Kurosawa created what many believe to be his last masterpiece Ran which is based on the story of King Lear and was Kurosawa’s goodbye to the samurai genre; he was in his late 70’s and half blind when shooting the film.

Most great films have one great moment that is considered iconic, and Ikiru has at least three of them. The first one that immediately comes to mind is the frightening sequence in the doctor’s office. Watanabe speaks to a patient before going into the doctor and the patient describes to Watanabe the precise symptoms and the doctor’s exact words when attributing it to stomach cancer. Like most of everyone’s worries when seeing the doctor, (I know it’s mine) Watanabe’s fears are unfortunately confirmed when the doctor uses the very words and descriptions that the patient earlier predicted, and the feeling of despair on Watanabe’s face is absolutely tragic. The second sequence is Watanabe when asking a complete stranger to help him spend his money on ‘having a good time’, because he doesn’t know how to spend it. The stranger takes him out on the town, to gambling parlors, dance halls and the red light district, and finally to a bar where the piano player calls for requests and Watanabe, still wearing his overcoat and hat, asks for the song ‘Life Is Short Fall in Love, Dear Maiden.’ The piano man says, “Oh, yeah, one of those old ’20s songs,” but when he plays it, Watanabe starts to softly sing to the song, barely moving his lips, and suddenly the bar becomes silent. For just a brief moment, these young drunken men and women are drawn into a deep existential contemplation on just how short and precious their lives really are. The third sequence is near the end of the film, when the park officer arrives at Watanabe’s wake and describes the last moment that Watanabe’s was seen alive. In an iconic moment in time Watanabe is sitting on a swing in the park, while the snow falls while quietly singing ‘Life is Brief’ while he proudly gazes over the playground he created, finally at peace with himself and the world; knowing he can die a happy man. This sequence is one of the most magical and emotional scenes ever committed to celluloid.

Ikiru for me will always be my personal favorite out of Kurosawa’s films because I can relate to it in many different ways. Every time I see this film again I’m a little older, more wiser and the motivations of Watanabe are much more understandable. For years I was like Watanabe, a man who worked at a corporate company like a mindless drone, just doing the same meaningless work over and over again. It didn’t really matter how much you accomplished because the harder you work, the more work they gave you. Everyone there hated their job and most of them have worked there 30 to 50 years. Most of the workers were bitter, angry and unhappy and a lot of the management there never gave their employeers much respect. It was a grunge job where you were just another body, and the work I was doing didn’t give me any importance or personal satisfaction. It was sad because most of the people there that I’d talk to said if they had to do it all over again they would be working somewhere else or of went back to school. The point I’m trying to get at is most people don’t live truly fulfilling lives. They get married, have several children but many feel there stuck at an unhappy job and are at a point of their life where they feel there’s no way out. Ikiru made me see that being truly happy and living your life to the fullest is the best accomplishment you can give yourself. It’s sad that most people only know Akira Kurosawa because of his samurai action films because he has created some of the greatest most humane films ever with masterpieces like Ikiru, Dersu Uzala and Red Beard. Not only is Ikiru one of the most life affirming films I have ever seen, it also shows you that if you really try at something that you have complete devotion to, you can accomplish your dreams. Roger Ebert included Ikiru in his Great Movies list in 1996 saying “Over the years I have seen Ikiru every five years or so, and each time it has moved me, and made me think. And the older I get, the less Watanabe seems like a pathetic old man, and the more he seems like every one of us,” and even considered it Kurosawa’s greatest film. It is currently ranked as the ninth most spiritually significant film of all time by the Arts and Faith online community. Ikiru ranks 459th on Empire magazine’s 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time and is ranked #44 in Empire magazines “The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema” in 2010. There are many people like Watanabe in this world and most of them either die not really living or they want to change but either are too weak or believe it’s too late to do so. Like the song Watanabe sings, ‘life is brief’, we as people should do our best to make the most of our short lives. Because of watching this film it made me quit my miserable job and find something that I am now happy doing. This film not only inspired me to truly live my life once again, but it also inspired me to create this website; so I can share to others beautiful films like this one.

Ikiru for me will always be my personal favorite out of Kurosawa’s films because I can relate to it in many different ways. Every time I see this film again I’m a little older, more wiser and the motivations of Watanabe are much more understandable. For years I was like Watanabe, a man who worked at a corporate company like a mindless drone, just doing the same meaningless work over and over again. It didn’t really matter how much you accomplished because the harder you work, the more work they gave you. Everyone there hated their job and most of them have worked there 30 to 50 years. Most of the workers were bitter, angry and unhappy and a lot of the management there never gave their employeers much respect. It was a grunge job where you were just another body, and the work I was doing didn’t give me any importance or personal satisfaction. It was sad because most of the people there that I’d talk to said if they had to do it all over again they would be working somewhere else or of went back to school. The point I’m trying to get at is most people don’t live truly fulfilling lives. They get married, have several children but many feel there stuck at an unhappy job and are at a point of their life where they feel there’s no way out. Ikiru made me see that being truly happy and living your life to the fullest is the best accomplishment you can give yourself. It’s sad that most people only know Akira Kurosawa because of his samurai action films because he has created some of the greatest most humane films ever with masterpieces like Ikiru, Dersu Uzala and Red Beard. Not only is Ikiru one of the most life affirming films I have ever seen, it also shows you that if you really try at something that you have complete devotion to, you can accomplish your dreams. Roger Ebert included Ikiru in his Great Movies list in 1996 saying “Over the years I have seen Ikiru every five years or so, and each time it has moved me, and made me think. And the older I get, the less Watanabe seems like a pathetic old man, and the more he seems like every one of us,” and even considered it Kurosawa’s greatest film. It is currently ranked as the ninth most spiritually significant film of all time by the Arts and Faith online community. Ikiru ranks 459th on Empire magazine’s 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time and is ranked #44 in Empire magazines “The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema” in 2010. There are many people like Watanabe in this world and most of them either die not really living or they want to change but either are too weak or believe it’s too late to do so. Like the song Watanabe sings, ‘life is brief’, we as people should do our best to make the most of our short lives. Because of watching this film it made me quit my miserable job and find something that I am now happy doing. This film not only inspired me to truly live my life once again, but it also inspired me to create this website; so I can share to others beautiful films like this one.