Hiroshima mon amour (1959)

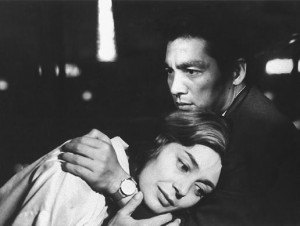

Hiroshima mon amour is one of the great poetic French films of all time that also became the major catalyst for the French New Wave using several innovative techniques such as several flashbacks, documentary footage and it's uniquely non linear storyline. Hiroshima mon amour was directed by the great French director Alain Resnais, and with a remarkable screenplay by Marguerite Duras, (which was nominated for an Academy Award) this film can be looked at as a series of literary conversations on a 36 hour period of a love affair between a married French actress (Emmanuelle Riva), referred to as 'She', and a married Japanese architect (Eiji Okada), referred to as 'He'. This film was made only fourteen years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and when watching this postmodern war film once again there are much deeper themes dwelling underneath the romantic storyline that documents the couples tragic history on their memories and forgetfulness. When the film was first screened, one of the films producers Anatole Dauman said to Resnais, "I've seen all this before, in Citizen Kane, a film which breaks chronology and reverses the flow of time." Resnais replied by saying, "yes, but in my film time is shattered." Hiroshima mon amour in English means 'Hiroshima, My Love', as the two lovers exercise their own scarred memories of love and suffering and how these memories and pain are a contrast to the horrible bombing on Hiroshima. The film uses highly structured repetitive dialogue and scenes, mostly consisting of Her narration, with Him interjecting to say she is wrong, lying, confused, or to deny and contradict her statements with the film's famous line "You are not endowed with memory". [fsbProduct product_id='845' size='200' align='right']Hiroshima mon amour’s reputation as a milestone in the movement of the French New Wave is both a blessing and a curse, as it is a difficult and challenging film for many modern viewers to take in, and its heavy and monumental subject matter can be emotionally draining. Unlike other films of the French New Wave most famously Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless which is much more freewheeling, and accessible to get involved in with its spontaneous edits and quick jump cuts; Hiroshima mon amour, like several of Resnais other films is much more intellectually challenging and emotionally devastating. The early part of Hiroshima mon amour recounts the disturbing aftermath of the bombing on Hiroshima in the style of a documentary as it flashes to news reel footage showing the effects of the Hiroshima bomb, in particular the loss of hair and the remains of some of the victims. The insertion of the documentary footage is interesting because Resnais was originally going to make a short documentary about the atomic bomb, but eventually decided to make it a feature-length film. Hiroshima mon amour in many ways is the story of two separate tragedies, one massive and global, the other small and private. When the film was first released the great French critic and director Eric Rohmer stated in a discussion with the members of the magazine of Cashier du Cinema, "I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty, or thirty years, we will know whether Hiroshima mon amour was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema."

Hiroshima mon amour is one of the great poetic French films of all time that also became the major catalyst for the French New Wave using several innovative techniques such as several flashbacks, documentary footage and it's uniquely non linear storyline. Hiroshima mon amour was directed by the great French director Alain Resnais, and with a remarkable screenplay by Marguerite Duras, (which was nominated for an Academy Award) this film can be looked at as a series of literary conversations on a 36 hour period of a love affair between a married French actress (Emmanuelle Riva), referred to as 'She', and a married Japanese architect (Eiji Okada), referred to as 'He'. This film was made only fourteen years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and when watching this postmodern war film once again there are much deeper themes dwelling underneath the romantic storyline that documents the couples tragic history on their memories and forgetfulness. When the film was first screened, one of the films producers Anatole Dauman said to Resnais, "I've seen all this before, in Citizen Kane, a film which breaks chronology and reverses the flow of time." Resnais replied by saying, "yes, but in my film time is shattered." Hiroshima mon amour in English means 'Hiroshima, My Love', as the two lovers exercise their own scarred memories of love and suffering and how these memories and pain are a contrast to the horrible bombing on Hiroshima. The film uses highly structured repetitive dialogue and scenes, mostly consisting of Her narration, with Him interjecting to say she is wrong, lying, confused, or to deny and contradict her statements with the film's famous line "You are not endowed with memory". [fsbProduct product_id='845' size='200' align='right']Hiroshima mon amour’s reputation as a milestone in the movement of the French New Wave is both a blessing and a curse, as it is a difficult and challenging film for many modern viewers to take in, and its heavy and monumental subject matter can be emotionally draining. Unlike other films of the French New Wave most famously Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless which is much more freewheeling, and accessible to get involved in with its spontaneous edits and quick jump cuts; Hiroshima mon amour, like several of Resnais other films is much more intellectually challenging and emotionally devastating. The early part of Hiroshima mon amour recounts the disturbing aftermath of the bombing on Hiroshima in the style of a documentary as it flashes to news reel footage showing the effects of the Hiroshima bomb, in particular the loss of hair and the remains of some of the victims. The insertion of the documentary footage is interesting because Resnais was originally going to make a short documentary about the atomic bomb, but eventually decided to make it a feature-length film. Hiroshima mon amour in many ways is the story of two separate tragedies, one massive and global, the other small and private. When the film was first released the great French critic and director Eric Rohmer stated in a discussion with the members of the magazine of Cashier du Cinema, "I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty, or thirty years, we will know whether Hiroshima mon amour was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema."

FILM/NOTES

The beautiful opening shot of the film shows arms embracing each other with the feel of ashes and dust coating the bodies as it dissolves with a real life couple holding one another. You hear the man say, "You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing." The woman says, "I saw everything. I saw the hospital...I'm sure of it." The film flashes back to shots of the Hiroshima hospital. "How could I not have seen it?" It shows several of the Japanese patients as they turn away from her. "You didn't see the hospital in Hiroshima. You saw nothing at the hospital in Hiroshima," he says.

"Four times at the museum," she says as the film flashes back to a Japanese museum where tourists are lost in thought and memories looking at photographs, reconstructed models and authentic films showing the bombing of Hiroshima which makes several tourists weep. She says, "I always wept over Hiroshima's fate. Always." The man says, "no. What was there for you to weep over?" She describes how she saw the newsreels of Hiroshima and the film flashes into real newsreel of the victims after the attack and there is frightening shots of young men and women whose faces are being reconstructed after being wounded.

The woman then says, "I saw the survivors too, and those who were in the wombs of the women of Hiroshima. I saw the patience, the innocence, the apparent meekness with which the temporary survivors of Hiroshima adapted to a fate so unjust that the imagination usually so fertile, is silent before it. Women risk giving birth to deformed children, to monsters, but it goes on. Men becoming sterile...but it goes on. Rain causes panic, the rain of ash on the water of the Pacific. The Pacific turns deadly, and its fishermen die. Food becomes an object of fear. An entire city's food is thrown away. The food of entire cities is buried. An entire city rises up in anger. But against whom do they rise up in anger? Like you, I am endowed with memory. I know what it is to forget."

The man says, "no, you are not endowed with memory..." She says, "like you, I struggled with all my might not to forget. Like you, I forgot. Like you, I longed for a memory beyond consolation, a memory of shadows and stone. Like you....I forgot." The flashbacks and documentary reels fade out with the hands of the women touching the back of the man's back with her saying, "you have such beautiful skin." The man laughs as he lays back in bed with her. She asks the man in bed if he is completely Japanese and he says he is. He says that her eyes are green which make her a thousand women in one but she says he thinks that because he doesn't know her. The woman asks if the man was in Hiroshima and he says his family was but he was off fighting the war. "Lucky for you, eh?" she says. "lucky for me too."

She explains to him that she is in Hiroshima because she is acting in a film. She then tells him she is from Paris and before Paris she grew up in a town called Nevers which is in the province of Nievre. He then asks her why she wanted to see everything in Hiroshima. She says, "it interested me. I have my own idea about it. For example, looking closely at things is something...that has to be learned." That next morning the woman is standing outside on the porch looking over at the city and when walking back in she smiles when glancing at her lover still sleeping as a flashback quickly shows her over a dead lover when she was a young girl.

When he wakes up she gets him coffee and asks what he was dreaming but he cannot remember. The next scene shows the both of them in the shower as he tells her how beautiful she is. He tells her when he first saw her she looked bored saying, "you were bored in a way that makes a man want to know a woman." She says that he speaks French well and he tells her he notices she doesn't speak Japanese saying, "have you ever noticed people have a way of noticing what they want?" They sit outside on the porch that over looks the large city of Hiroshima and she tells the man that meeting a lover in Hiroshima doesn't happen every day. "What did Hiroshima mean to you in France?" he asks her. She thinks for a moment and says, "the end of the war...I mean completely. Astonishment that they dared do it...and astonishment that they succeeded. And the beginning of an unknown fear for us as well. And then indifference. And fear of indifference as well."

When he asks where she was at that time of the bombing she tells him she just left Nevers and was living on the streets of Paris. When he says how the word 'Nevers' is a beautiful word she heads inside the apartment. He follows asking if he is the first Japanese in her life and she says yes. He then says, "Hiroshima, the whole world rejoiced, and you rejoiced with it." She asks what he does for a living and he says he is an architect and is involved in politics which is why he speaks French so well. He asks her what kind of film she is in and she says it is a film about peace as she plays a small role as a French nurse. He then says how he wants to see her again, but she tells him she will be on her way back to France the next day.

"That's why you let me come to your room last night." he says. "Because it was your last day in Hiroshima." She says that is not true and he says, "when you speak, I wonder whether you lie or tell the truth." She says, "I lie...and I tell the truth. But I have no reason to lie to you." He again asks to see her again before she leaves but she says no. They both leave the apartment and head outside, and he asks her when she heads back to France if she will go back to Nevers. She says she hasn't been back there since she was very young, because of the pain. She tells him that Nevers is the one city she dreams about the most and thinks about the least. He again asks to see her again but she again says no and when her ride arrives she gets in and takes off.

The next shot is the making of the Hiroshima film as you see props, lighting, cameras and an assistant director. He comes to visit her on the set as she is sitting down next to a white cat. He asks her if the film that she is making is a French film and she tells him it's an international film on peace; and she just has a few more shots to do that involve crowd scenes and then she is finished. He says to her, "here in Hiroshima we don't make fun of films about peace." He tells her that she gives him a tremendous desire to love and in a poignant moment he slowly removes her artificial nurse cap revealing her hair and her real self. She believes it's just a short-lived affair between the two of them but he has never felt anything this strong.

There is an extraordinary shot of the both of them watching a political protest march being filmed as they stand next to an extra who is all made up in makeup to look like one of the Hiroshima victims that were caught in the blast. That shot shows an interesting contrast of a film within a film. The protest march shows people carrying slogans, banners and signs with one of them saying, "Unfortunately man's political intelligence is 100 times less developed than his scientific intelligence, and for that reason he forfeits our respect." He holds her during this and says to her how he thinks he loves her and begs her to come see him once more.

She finally agrees and they head back to the man's home while his wife is in the mountains in Unzen, and wont be back for a few days. She asks what his wife is like and he says, "beautiful. I'm a man who's happy with his wife." She smiles and says, "so am I. I am a woman who is happy with her husband." The two embrace and make love. In bed, he asks her if the man she loved during the war was French. She tells him he was not French as the film flashes back to when she was a young girl in Nevers riding her bike. She tells him that they met secretly at the barns, then among the ruins and eventually in rooms. The man then died when she was 18 and he was 23. The man she had an affair with was a German soldier and because of that she got severely punished for the affair; getting her hair cut off and was imprisoned in a damp and cold cellar. "Why speak of him and not others?" she asks.

He says, "because of Nevers. I'm only just beginning to know you, and from the many thousands of things in your life...I choose Nevers. I somehow understand that it was there that I almost lost you...and ran the risk of never, ever meeting you. I somehow understand that it was there...that you began to be who you are today..." In the early morning when the woman wakes up she shouts "I want to leave this place!" and yet embraces the man knowing she truly doesn't want to leave. Later that morning she has sixteen hours before she has to leave and fly back to France and they both decide to spend her last hours together. The two of them arrive at a tea room and when sitting down, he is still interested in her scarred childhood when living in Nevers; wanting her to reveal more of her mysterious past.

She eventually opens up and goes into complete detail on her hometown in Nevers. She says, "Population 40,000. Built like a capital. A child can walk all the way around it." It then flashes back when she was locked in a cellar when she was 20 and how horrifying the experience was for her. When narrating the story the Japanese man slowly transitions into the German man as he then asks her if he was dead to her when she was locked in the cellar. They hold each others hands as she says, "hands become useless in a cellar. They claw and scrape away at the rocks until they bleed." She describes how her father preferred her punishment and how he was ashamed that she disgraced the family.

In time they released her from the cellar and the family confined her to her bedroom and then returned her back to the cellar because of her hate on her own people. He asks her if the cellar she was locked in was old and damp. She says it was as she describes a black cat roaming in and she says, "afterwards I don't remember anymore." Someone in the tea room plays a record as the woman continues to describe her painful experience in Nevers as she describes her hair eventually growing back after being released from the cellar. The man asks what it was like getting her hair shaved and the film flashes back to show her in a line of other disgraceful women getting her hair forcefully cut off as crowds of people laugh and mock her suffering and pain as she is paraded around town because of her betrayal of sleeping with the enemy.

She then describes how over time she began to forget her love and the memory of him. The film flashes back to her when she was having an affair with her German lover and how they promised to meet at the banks of the Loire at noon. But when she arrived he was shot and slowly bleeding to death as she stayed with his body all day and night as Nevers then became liberated.She says, "the moment of his death actually escapes me, because at that moment and even afterwards...I couldn't find the slightest difference between his dead body and my own. His body and mine seemed to me to be one and the same. You understand? He was my first love!"

He then slaps her back in reality as the customers in the tea room all look over at them. She then tells him that they eventually let her out of the cellar because she became reasonable once again and the hate she once felt on her own people had left her heart. After out of the cellar her mother tells her that she must leave for Paris, giving her money and forces her to leave Nevers on a bicycle during that summer. When she arrived in Paris a few days later Hiroshima was in the papers and her hair grown back to a decent length...and now fourteen years have passed. She then tells him how she doesn't even remember her childhood lover much anymore and can't even remember his hands. She then says how she will one day no longer remember this evening with the Japanese lover as well. She says to him, "tomorrow at this time, I'll be thousands of miles from you."

The man is surprised to learn that her husband doesn't know about the story of her painful childhood in Nevers and that he is the only one she has told that story to, which greatly pleases him. He then says to her, "in a few years, when I have forgotten you, and other adventures like this one will happen to me from sheer force of habit, I'll remember you as the symbol of love's forgetfulness. I'll think of this story as the horror of forgetting."

Admiring all the lights and how alive the city is even in the late night, she tells him how she loves the city of Hiroshima because there is always someone who is awake during all the hours of the day. They both leave the tea room and step outside and she tells him, "sometimes we have to avoid thinking about the problems life presents. Otherwise we'd suffocate. We'll probably die without ever seeing each other again." He says, "yes, probably. Unless, perhaps, one day...a war..."

The two of them then go their separate ways as the woman heads back to her hotel but she is tortured on leaving this lover of hers. "You think you know...but no...never...She starts to talk out loud to herself on how angry she was to openly tell a stranger on her secret love affair of her childhood, and how it's been fourteen years since she had a forbidden love again since Nevers. The woman decides to head to the tea room and sits outside thinking to herself on how she wants to stay in Hiroshima with this man she now loves. Suddenly the Japanese man approaches her and asks her to stay in Hiroshima and she impulsively agrees. She says, "I'm so miserable! I wasn't expecting this at all. You understand?"

She then realizes this is wrong and tells him to go away as she starts walking away. Now it being the early morning, she finds herself walking down the streets of Hiroshima with him not so far behind begging her to stay. While walking past several shops, brothels and restaurants in Hiroshima she thinks to herself, "I meet you. I remember you. This city was tailor-made for love. You fit my body like a glove. Who are you? You're destroying me. I was hungry...hungry for infidelity, for adultery, for lies, and for death. I always had been." She finally comes to her senses and realizes she cannot stay in Hiroshima. When confronting the man again at the tea room she tells him the decision she has come to. He begs her for three more days and she says, "neither time enough to live from it, nor time enough to die from it. So I don't give a damn."

He tells her that he would had prefered she had died in Nevers and she says, "so would I. But I didn't die in Nevers." She then walks off and arrives at a rest spot and sits down on a bench and to the left of her is a little Japanese old lady. The woman thinks to herself, "Nevers, you whom I'd forgotten...tonight I'd like to see you again." Suddenly the man appears and sits down to the right of the elderly lady, with the elderly lady sitting between the two tortured lovers. He then reaches over and offers the woman a cigarette and she thinks, "while my body is still ablaze with the memory of you, I'd like to see Nevers once again. The Loire..." She then thinks back to all the places and memories of Nevers and of her innocence that died there when she was younger. The elderly lady asks the man in Japanese who the woman is and he tells her a French woman who is leaving Japan and is sad they have to leave each other.

When the camera pans back to the woman she is gone as it shows her taking a cab and heading to a night club called the Casablanca and while there she gets hit on by another man while the Japanese man arrives and watches from another table. This scene is interesting because you can tell from the man's expression while watching this other man trying to pick the woman up that he probably did the same exact thing to her 24 hours earlier.

The woman purposely misses her flight home and heads back to her hotel room as the Japanese man comes up because he had to see her, one last time. She starts to cry and screams out, "I'll forget you! I'm forgetting you already! Look how I'm forgetting you! Look at me!" The two of them stare intensely in each other's eyes as she then calls him the only name she identifies him with which is Hiroshima, and he calls her the name that he identifies her with which is Nevers.

FRENCH NEW WAVE

The New Wave was a blanket term coined by critics for a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Although never a formally organized movement, the New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of the literary period pieces being made in France and written by novelists, their spirit of youthful iconoclasm, the desire to shoot more current social issues on location, and their intention of experimenting with the film form. "New Wave" is an example of European art cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm.

Using light-weight portable equipment, hand-held cameras and requiring little or no set up time, the New Wave way of film-making presented a documentary style. The films exhibited direct sounds on film stock that required less light. Filming techniques included fragmented, freeze-frames, discontinuous editing, and long takes. The combination of objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary created a narrative ambiguity in the sense that questions that arise in a film are not answered in the end.

Alexandre Astruc's manifesto, "The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera-Stylo", published in L`Ecran, on 30 March 1948 outlined some of the ideas that were later expanded upon by François Truffaut and the Cahiers du cinéma. It argues that "cinema was in the process of becoming a new mean of expression on the same level as painting and the novel: a form in which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel. This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the 'camera-stylo."

Some of the most prominent pioneers among the group, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, began as critics for the famous film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Cahiers co-founder and theorist André Bazin was a prominent source of influence for the movement. By means of criticism and editorialization, they laid the groundwork for a set of concepts, revolutionary at the time, which the American film critic Andrew Sarris called the 'auteur theory.'

Cahiers du cinéma writers critiqued the classic "Tradition of Quality" style of French Cinema. Bazin and Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, were the dual godfather figures of the movement. These men of cinema valued the expression of the director's personal vision in both the film's style and script.

The 'auteur theory' holds that the director is the "author" of his movies, with a personal signature visible from film to film. They praised movies by Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, and made then-radical cases for the artistic distinction and greatness of Hollywood studio directors such as Orson Welles, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray. The beginning of the New Wave was to some extent an exercise by the Cahiers writers in applying this philosophy to the world by directing movies themselves.

Truffaut, with The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard, with Breathless (1960) had unexpected international successes, both critical and financial, that turned the world's attention to the activities of the New Wave and enabled the movement to flourish. Part of their technique was to portray characters not readily labeled as protagonists in the classic sense of audience identification.

The auteurs of this era owe their popularity to the support they received with their youthful audience. Most of these directors were born in the 1930s and grew up in Paris, relating to how their viewers might be experiencing life. They were considered the first film generation to have a "film education", knowledge of and references to film history. With high concentration in fashion, urban professional life, and all-night parties, the life of France's youth was being exquisitely captured.

The French New Wave was popular roughly between 1958 and 1964, although New Wave work existed as late as 1973. The socio-economic forces at play shortly after World War II strongly influenced the movement. Politically and financially drained, France tended to fall back on the old popular pre-war traditions. One such tradition was straight narrative cinema, specifically classical French film.

The movement has its roots in rebellion against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), criticizing in particular the way these forms could force the audience to submit to a dictatorial plot-line. They were especially against the French "cinema of quality", the type of high-minded, literary period films held in esteem at French film festivals, often regarded as 'untouchable' by criticism.

The movement has its roots in rebellion against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), criticizing in particular the way these forms could force the audience to submit to a dictatorial plot-line. They were especially against the French "cinema of quality", the type of high-minded, literary period films held in esteem at French film festivals, often regarded as 'untouchable' by criticism.

New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what was, to them, a much more comfortable and contemporary form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized. French New Wave were also influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema.

The French New Wave featured unprecedented methods of expression, such as long tracking shots (like the famous traffic jam sequence in Godard's 1967 film Week End). Also, these movies featured existential themes, such as stressing the individual and the acceptance of the absurdity of human existence. Filled with irony and sarcasm, the films also tend to reference other films.

Many of the French New Wave films were produced on tight budgets; often shot in a friend's apartment or yard, using the director's friends as the cast and crew. Directors were also forced to improvise with equipment (for example, using a shopping cart for tracking shots). The cost of film was also a major concern; thus, efforts to save film turned into stylistic innovations. For example, in Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, after being told the film was too long and he must cut it down to one hour and a half he decided (on the suggestion of Jean-Pierre Melville) to remove several scenes from the feature using jump cuts, as they were filmed in one long take. Parts that did not work were simply cut from the middle of the take, a practical decision and also a purposeful stylistic one.

The cinematic stylings of French New Wave brought a fresh look to cinema with improvised dialogue, rapid changes of scene, and shots that go beyond the common 180° axis. The camera was used not to mesmerize the audience with elaborate narrative and illusory images, but to play with the expectations of cinema. The techniques used to shock and awe the audience out of submission and were so bold and direct that Jean-Luc Godard has been accused of having contempt for his audience. His stylistic approach can be seen as a desperate struggle against the mainstream cinema of the time, or a degrading attack on the viewer's supposed naivety. Either way, the challenging awareness represented by this movement remains in cinema today. Effects that now seem either trite or commonplace, such as a character stepping out of their role in order to address the audience directly, were radically innovative at the time.

Classic French cinema adhered to the principles of strong narrative, creating what Godard described as an oppressive and deterministic aesthetic of plot. In contrast, New Wave filmmakers made no attempts to suspend the viewer's disbelief; in fact, they took steps to constantly remind the viewer that a film is just a sequence of moving images, no matter how clever the use of light and shadow. The result is a set of oddly disjointed scenes without attempt at unity; or an actor whose character changes from one scene to the next; or sets in which onlookers accidentally make their way onto camera along with extras, who in fact were hired to do just the same.

At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods, and were inspired by the generation of Italian Neorealists before them. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to the theatre.

Finally, the French New Wave, as the European modern Cinema, is focused on the technique as style itself. A French New Wave film-maker is first of all an author who shows in its film his own eye on the world. On the other hand the film as the object of knowledge challenges the usual transitivity on which all the other cinema was based, "undoing its cornerstones: space and time continuity, narrative and grammatical logics, the self-evidence of the represented worlds." In this way the film-maker passes "the essay attitude, thinking – in a novelist way – on his own way to do essays."

The Left Bank, or Rive Gauche, group is a contingent of filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, first identified as such by Richard Roud. The corresponding "right bank" group is constituted of the more famous and financially successful New Wave directors associated with Cahiers du cinéma. Unlike the Cahiers these directors were older and less movie-crazed. They tended to see cinema akin to other arts, such as literature. However they were similar to the New Wave directors in that they practiced cinematic modernism. Their emergence also came in the 1950s and they also benefited from the youthful audience. The two groups, however, were not in opposition; Cahiers du cinéma advocated Left Bank cinema.

Left Bank directors include Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. Roud described a distinctive "fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking", as well as an identification with the political left. The filmmakers tended to collaborate with one another, Jean-Pierre Melville, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Marguerite Duras are also associated with the group. The nouveau roman movement in literature was also a strong element of the Left Bank style, with authors contributing to many of the films. Left Bank films include La Pointe Courte, Hiroshima mon amour, La jetée, Last Year at Marienbad, and Trans-Europ-Express.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

“I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty, or thirty years, we will know whether Hiroshima mon amour was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema.” That’s Eric Rohmer, in a July 1959 round-table discussion between the members of Cahiers du Cinéma’s editorial staff, devoted to Alain Resnais’ groundbreaking first feature. Rohmer’s remark is in perfect sync with the spirit of the film, which, as he says later in the discussion, “has a very strong sense of the future, particularly the anguish of the future.” Read nearly half a century later, this “anguish of the future” describes the peculiar sensation that runs through all of Resnais’ films, before and after Hiroshima. In fact, it’s the anguish of past, present, and future: the need to understand exactly who and where we are in time, a need that goes perpetually unsatisfied.

Is Rohmer’s query a useful one? Can it even be answered? Many would offer alternative candidates for the first modern film of the sound era—Citizen Kane, perhaps, or Voyage to Italy, or perhaps a dark horse like His Girl Friday or Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. Or, for that matter, Resnais’ own Night and Fog. But it’s possible that Hiroshima mon amour is the first modern sound film in every aspect of its conception and execution—construction, rhythm, dialogue, performance style, philosophical outlook, and even musical score.

Whether or not it’s the most important film since the war is another question altogether, and an oddly poignant one. Because looking for a “most important film since the war” may strike many of us today, in our spectacle-saturated world of capitalism unbound, as a quaint enterprise. Those among us who recognize “the war” as a historical benchmark, without a reminder from Hollywood or the Discovery Channel, are dwindling. In 1959, just fourteen years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Rohmer and his estimable cohorts (including Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Rivette) probably had something quite specific in mind with their quest to find a genuinely modern postwar cinema, one that would respond to the moral imperative of the moment (exemplified by Theodor Adorno’s famous banishment of lyricism after the Holocaust), and then somehow define that moment for all time. A tall order. The fact that Resnais’ unflinching film comes within hailing distance of accomplishing such an impossible task is a tribute to its greatness.

Hiroshima mon amour’s status as a milestone in film history is both a blessing and a curse. It can be hard for new audiences to find their way to the actual movie, buried as it is beneath its own daunting reputation, monumental subject matter, and high cultural pedigree. Unlike Breathless, with its jump cuts and light, spontaneous feel, Hiroshima is deliberate, highly constructed, decidedly grave, and emotionally devastating. Where Godard is loose-limbed, Resnais has a spine of modernist steel. Where the Godard film feels like a free-jazz improvisation, the Resnais feels like a piece of atonal music with the weight of history on its shoulders—Ornette Coleman vs. Anton Webern. Such seriousness of purpose is now considered a high crime in most critical circles. But that’s a passing fad, and no allowances or apologies are needed for the terrible beauty wrought by Resnais and his key collaborator, the great Marguerite Duras.

It’s difficult to quantify the breadth of Hiroshima’s impact. It remains one of the most influential films in the short history of the medium, first of all because it liberated moviemakers from linear construction. Without Hiroshima, many films thereafter would have been unthinkable, from I Fidanzati to The Pawnbroker to Point Blank to Petulia to Don’t Look Now (and almost every other Nicolas Roeg movie) to Out of Sight and The Limey. After he screened the answer print, Anatole Dauman, one of the film’s producers, told Resnais, “I’ve seen all this before, in Citizen Kane, a film which breaks chronology and reverses the flow of time.” To which Resnais replied, “Yes, but in my film time is shattered.” As it is, often for less dramatically compelling and sometimes more fanciful reasons, in many of the above films.

But Hiroshima has also had another kind of impact, one less easy to trace. In laying out the particulars of this wholly new film and its relationship to the “nouveau roman,” Rivette made a very important point. He compared Resnais to novelist Pierre Klossowski : “For Klossowski and for Resnais,” he said, “the problem is to give the readers or the viewers the sensation that what they are going to read or see is not an author’s creation but an element of the real world.” This is, once again, a postwar aspiration, completely in keeping with Adorno’s dictum, which ran through all the arts. In cinema, there had already been many films (such as Citizen Kane) that had used reality effects to enhance the impact of their fictions. In the postwar era, beginning with neorealism, certain key filmmakers worked so that reality might maintain its integrity and declare its presence without having to blend into an artificially constructed fiction. Godard took the road staked out by Roberto Rossellini, dissolving the barriers between film time and real time, fictional space and real space, stories and documentaries. But Resnais worked in a vein more reminiscent of Sergei Eisenstein, erecting a complex, rhythmically precise fictional construction in which pieces of reality are caught and allowed to retain their essential strangeness and ominous neutrality. Resnais has always been recognized as an innovator, but the term has a hollow ring. As a morally responsible artist committed to catching pieces of unaltered reality in a carefully constructed net of fiction, he has paved the way for many filmmakers, from the Francesco Rosi of Salvatore Giuliano to the Dusan Makavejev of WR to the Scorsese of Goodfellas and Casino to the Terrence Malick of The Thin Red Line.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising that Hiroshima mon amour began not as a fiction, but as a documentary. Dauman had successfully pitched the idea of a project about the bomb and its impact to Daiei Studios, and it was to be the first Japanese-French co-production. The title would be Picadon, the “flash” of the A-bomb explosion. It was only after months of reflection that Resnais settled on the idea that Picadon should be a fiction, and that the impact of Hiroshima would be refracted through the viewpoint of a foreign woman. It was Resnais who brought Duras to the project, at the end of the decade when she had achieved literary stardom with Un barrage contre le Pacifique and Moderato Cantabile. It took Duras all of two months to turn out a finished script, all the while working closely with her director. Although Resnais’ links to Eisenstein seem obvious, Griffith’s Intolerance was the film he and Duras had in their heads. “Marguerite Duras and I had this idea of working in two tenses,” he told Parisian journalist Joan Dupont in a recent interview. “The present and the past coexist, but the past shouldn’t be in flashback…. You might even imagine that everything the Emmanuelle Riva character narrated was false; there’s no proof that the story she recites really happened. On a formal level, I found that ambiguity interesting.”

It’s often been said that Resnais is not an auteur in the proper sense, since the presence of his writers—Duras, Robbe-Grillet, Jorge Semprun, David Mercer, Jacques Sternberg, Jean Gruault, Jules Feiffer—is so deeply embedded in the finished products. But Resnais’ relationship with his writers is not very different from the relationship between, say, Howard Hawks and Jules Furthman. Only the sensibilities differ. “I’m always in search of special nonrealistic language that has musicality,” Resnais told Dupont, and he has gone out of his way to find writers with distinctively musical voices, many of them with little if any previous experience in movies . In a sense, Resnais could be thought of as the Pierre Boulez of cinema, a brilliant impresario with a mission to attune our eyes and ears to the sights and sounds of modernism (that would be Boulez the conductor, not the composer). But this “conductor” has always worked closely with his “composers” on shaping an object of which they are finally the co-creators. Resnais’ imagination is obviously sparked by sound, by music and words, and the music of words. The musical speech of memory that emanates from Duras’ characters sets a dominant tone against which the jagged ruptures in time and visual rhythm—sometimes like cut crystal, sometimes like rushing water—form a precise, often mysterious, always dynamic counterpoint.

Is Hiroshima mon amour the story of a woman? Or is it the story of a place where a tragedy has occurred? Or of two places, housing two separate tragedies, one massive and the other private? In a sense, these questions belong to the film itself. The fact that Hiroshima continues to resist a comforting sense of definition almost fifty years after its release may help to account for Resnais’ nervousness when he set off for the shoot in Japan. He was convinced that his film was going to fall apart, but the irony is that he and Duras had never meant for it to come together in the first place. What they created, with the greatest delicacy and emotional and physical precision, was an anxious aesthetic object, as unsettled over its own identity and sense of direction as the world was unsettled over how to go about its business after the cataclysmic horror of World War II. With its narrative of an actress going to Hiroshima (to play a part in a film “about peace”) expecting to erase her tragic past, only to see her memories magnified by the greater collective memory of atomic destruction, Hiroshima never locates a fixed point toward which emotion, morality and ethics gravitate. The magnificent Emmanuelle Riva is less the “star” of the film than its primary “soloist,” to extend the musical metaphor––in comparison, Eiji Okada’s architect-lover is more of a first violin type. There is a dominant motif, which is the sense of being overpowered, ravished, taken––a French woman who wants to be overpowered by her Japanese lover (“Take me. Deform me, make me ugly”), an Asian man who is consumed by his Western lover’s beauty and unknowability, a fictional peace rally overwhelmed by its real-life antecedent, everyday reality drowned out by a flood of memories, a city devastated by nuclear force.

“Hi-ro-shi-ma. That’s your name.” “That’s my name. Yes. Your name is Nevers. Ne-vers in France.” Appropriately for a film about the anxiety of irresolution, the end doesn’t tie up loose ends as much as it suggests a new and sober starting point. It’s a moment of realization that feels neither tragic nor affirmative, just crushingly exact. But there is another endpoint, a spiritual one, and it comes early—the final statement of the film’s famous and eternally alarming opening section. We are looking at shots of a rebuilt Hiroshima, a tourist attraction less than fifteen years after it had been levelled, probably filled with people like Riva’s actress, unconsciously and mistakenly expecting to see their own personal tragedies rendered insignificant in the shadow of a monumental tragedy. Resnais’ beautifully calibrated images move in sinuous counterpoint to Duras’––and Riva’s––verbal music. And we hear the actress’ sad voice carefully reciting the words that still ring true today, and probably always will:

“Listen to me. I know something else. It will begin all over again. Two hundred thousand dead. Eighty thousand wounded. In nine seconds. These figures are official. It will begin all over again. It will be ten thousand degrees on the earth. Ten thousand suns, they will say. The asphalt will burn. Chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised from the earth and fall back in ashes….”

-Kent Jones

Alain Resnais film Hiroshima mon amour is a very difficult and challenging film for many modern viewers to take in. It's a very deep film with a heavy and monumental subject matter that is highly constructed and emotionally draining. Unlike other films of the French New Wave like Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless which is much more freewheeling, and accessible to get involved in with its quick jump cuts and hip spontaneous feel; Hiroshima mon amour, like several of Resnais other films are much more intellectually challenging. The non linear storyline construction that was introduced in Hiroshima was very groundbreaking and influential for the medium of film which influenced most obviously the films of Nicolas Roeg.

When the film was first screened, one of the films producers Anatole Dauman said to Resnais, "I've seen all this before, in Citizen Kane, a film which breaks chronology and reverses the flow of time." Resnais replied by saying, "yes, but in my film time is shattered." Film director and critic Jacques Rivette made an interesting comparison to the dialog of this film to the novelist of Pierre Klossowski saying, "For Klossowski and for Resnais, the problem is to give the readers or the viewers the sensation that what they are going to read or see is not an author's creation but an element of the real world." Resnais has always been looked at as an innovator of his films who influenced the work of Francesco Rosi and Dusan Makavejev.

What's interesting is how the idea of Hiroshima mon amour first came about. It was first conceived as a documentary short which was going to be about the A-bomb explosion and was even titled Picadon. After several months of thinking the idea over, Resnais realized that Picadon should be a story of fiction and that the impact of Hiroshima would be reflected through the eyes of a French woman. Resnais style has always been linked with the great Russian silent director Sergei Eisenstein but it was D.W. Griffith's intolerance that Resnais had in his mind when making the film. Resnais had Marguerite Duras join the project and write the script and Resnais said in an interview, "Marguerite Duras and I had this idea of working in two tenses. The present and the past coexist, but the past shouldn't be in flashback...you might even imagine that everything the Emmanuelle Riva character narrated was false; there's no proof that the story she recites really happened. On a formal level, I found that ambiguity interesting."

Alain Resnais is one of the most creative French directors of all time. He started out directing a lot of political films and documentaries in the beginning of his career; most importantly Night in Fog which is considered not only one of the greatest documentaries of all time but the most crucial for everyone to see. It was one of the first documentaries that went inside Nazi Germany’s death camps; and is a very disturbing but historically important film. Last Year at Marienbad is Resnais's masterpiece as it is an ambiguous story of a man and a woman who may or may not have met Last Year at Marienbad; and the themes of memory, flashbacks and dreams are very similar to Hiroshima mon amour. The characters like the characters in Hiroshima mon amour are nameless as well and are identified as A, X, and M. Then Resnais made Providence; a film starring Dirk Bogarde and Ellen Burstyn, which tells the story of a bitter man who spends one tormenting night in his bed suffering from health problems and thinking up a story based on his relatives. Muriel tells the story of a town in Boulogne where a woman sells antique furniture, living with her step-son, Bernard, who’s back from military duty in Algiers. Mon Oncle D’ Amerique is about a professor who uses the stories of the lives of three people to discuss behaviorist theories of survival, combat, rewards and punishment.

Resnais had a personal love for cats and in this film two different cats make an appearance in the story. The first cat is white and shows up when the woman is filming the Hiroshima film which she says is an international film on peace which might reflect the cat being white. When one of her flashbacks of her being confined in a cellar as a young girl for sleeping with a German officer, a black cat emerges which could symbolize the theme of death and decay. In his book on Resnais, James Monaco ends his chapter on Hiroshima mon amour by claiming that the film contains a reference to the classic 1942 film Casablanca which is the nightclub that he and she enter in the early morning. He describes how the film is like the story of the 1942 classic where it's about an impossible love between two people struggling with the war and where it's a fight for love and glory. The film tells two stories: one that is massive and global and one that is small and private. An underlying theme of the film is how war can affect people in different ways. For instance, the French woman will never know what the real horror of Hiroshima felt like and will always just be a tourist who sees Hiroshima as a tourist attraction through miniature models and black and white photographs. And yet she uses the Hiroshima tragedy as a way to see her own personal tragedies of her sad and scarring childhood. In some ways her affair and childhood trauma, even if completely different from the monumental tragedy of Hiroshima makes for an interesting parallel, with her wanting to obliviate the affair knowing the tragic consequences that will eventually come about; similar to the obliviatation of the Japanese people with the bomb which also brought tragic consequences. The most obvious one though is the loss of her hair when she was a young women which is a contrast to the loss of thousands of victims hair in the horrific aftermath of the bombing. Even though she experienced things much more different from the victims of Hiroshima; she still is haunted by that tragic day with the loss of her true love; but her memories and feelings are completely different. Memory is a large theme that is brought up through out the film from time to time and when the two lovers ask each other what they were doing on the day of the Hiroshima bombing; they can both remember it clearly. I of course am to young to have lived through Hiroshima but when the horrific attacks of the two towers on September 11th occurred I can remember exactly what I was doing like it was yesterday; and I'll probably never forget it. Like a lot of Resnais' work the ending in Hiroshima mon amour is left ambiguous and the ending doesn't really tie up loose ends. Does she decide to stay in Hiroshima and not return to her husband? Does he decide to leave his wife to be with her? That last scene of the film, the two nameless characters refer to each other as 'Hiroshima' and 'Nevers.' Even though the fate of these characters are left unknown these two lovers use the names of these tragic incidences and merge them with each other as it seems is the only way for the two of them to acknowledge one another and is a way they will remember each other. Hiroshima mon amour is a very poetic and powerful art film and one of the comments the woman makes in the film is still very relevant today and always will be: "Listen to me. I know something else. It will begin all over again. Two hundred thousand dead. Eighty thousand wounded. In nine seconds. These figures are official. It will begin all over again. It will be ten thousand degrees on the earth. Ten thousand suns, they will say. The asphalt will burn. Chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised from the earth and fall back in ashes..."

Resnais had a personal love for cats and in this film two different cats make an appearance in the story. The first cat is white and shows up when the woman is filming the Hiroshima film which she says is an international film on peace which might reflect the cat being white. When one of her flashbacks of her being confined in a cellar as a young girl for sleeping with a German officer, a black cat emerges which could symbolize the theme of death and decay. In his book on Resnais, James Monaco ends his chapter on Hiroshima mon amour by claiming that the film contains a reference to the classic 1942 film Casablanca which is the nightclub that he and she enter in the early morning. He describes how the film is like the story of the 1942 classic where it's about an impossible love between two people struggling with the war and where it's a fight for love and glory. The film tells two stories: one that is massive and global and one that is small and private. An underlying theme of the film is how war can affect people in different ways. For instance, the French woman will never know what the real horror of Hiroshima felt like and will always just be a tourist who sees Hiroshima as a tourist attraction through miniature models and black and white photographs. And yet she uses the Hiroshima tragedy as a way to see her own personal tragedies of her sad and scarring childhood. In some ways her affair and childhood trauma, even if completely different from the monumental tragedy of Hiroshima makes for an interesting parallel, with her wanting to obliviate the affair knowing the tragic consequences that will eventually come about; similar to the obliviatation of the Japanese people with the bomb which also brought tragic consequences. The most obvious one though is the loss of her hair when she was a young women which is a contrast to the loss of thousands of victims hair in the horrific aftermath of the bombing. Even though she experienced things much more different from the victims of Hiroshima; she still is haunted by that tragic day with the loss of her true love; but her memories and feelings are completely different. Memory is a large theme that is brought up through out the film from time to time and when the two lovers ask each other what they were doing on the day of the Hiroshima bombing; they can both remember it clearly. I of course am to young to have lived through Hiroshima but when the horrific attacks of the two towers on September 11th occurred I can remember exactly what I was doing like it was yesterday; and I'll probably never forget it. Like a lot of Resnais' work the ending in Hiroshima mon amour is left ambiguous and the ending doesn't really tie up loose ends. Does she decide to stay in Hiroshima and not return to her husband? Does he decide to leave his wife to be with her? That last scene of the film, the two nameless characters refer to each other as 'Hiroshima' and 'Nevers.' Even though the fate of these characters are left unknown these two lovers use the names of these tragic incidences and merge them with each other as it seems is the only way for the two of them to acknowledge one another and is a way they will remember each other. Hiroshima mon amour is a very poetic and powerful art film and one of the comments the woman makes in the film is still very relevant today and always will be: "Listen to me. I know something else. It will begin all over again. Two hundred thousand dead. Eighty thousand wounded. In nine seconds. These figures are official. It will begin all over again. It will be ten thousand degrees on the earth. Ten thousand suns, they will say. The asphalt will burn. Chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised from the earth and fall back in ashes..."