Gospel According to St. Matthew, The (1964)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Gospel According to St. Matthew 1964″ num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Only Pier Paolo Pasolini, an artist who was an atheist, a Marxist, and a homosexual could have made such an authentic and effective film on the life and death of Jesus Christ. Perhaps it was because the story was adapted by a nonbeliever who did not preach, glorify, sentimentalize or romanticize the famous story; and instead did his best to simply record it. According to Barth David Schwartz’s book Pasolini Requiem the impetus for the film took place in 1962. Pasolini had accepted Pope John XXIII’s invitation for a new dialogue with non-Catholic artists, and subsequently visited the town of Assisi to attend a seminar at a Franciscan monastery there. The papal visit caused traffic jams in the town, leaving Pasolini confined to his hotel room; there, he came across a copy of the New Testament. Pasolini read all four Gospels straight through, and he claimed that adapting a film from one of them “threw in the shade all the other ideas for work I had in my head.” The result was his film The Gospel According to St. Matthew which was filmed mostly in the poor, desolate Italian district of Basilicata, and its capital city, Matera. (Mel Gibson would film The Passion of the Christ on the very same locations forty years later.) Unlike previous cinematic depictions of Jesus’ life, Pasolini’s film does not embellish the biblical account with any literary or dramatic inventions, nor does it present an amalgam of the four Gospels. Pasolini stated that he decided to remake the Gospel by analogy and the film’s sparse dialogue all comes directly from the Gospel of Matthew, as Pasolini felt that “images could never reach the poetic heights of the text.” He reportedly chose Matthew’s Gospel over the others because he had decided that “John was too mystical, Mark too vulgar, and Luke too sentimental.” Pasolini’s Christ is played by Enrique Irazoqui, a Spanish economics student who had never acted before, and simply arrived to talk to Pasolini about his work. For his other roles, Pasolini cast local peasants, shopkeepers, factory workers, truck drivers, and for the role of Mary at the time of the Crucifixion, Pasolini casted his own mother. The shooting of non-actors, on real locations followed the style of the Italian Neorealist movement, which was a style that attempted to give a new degree of realism to the cinema. This was certainly the case with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, which chronicles the life of Christ as if a documentarian on a low budget had been following him from birth. First and foremost [fsbProduct product_id=’772′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Pasolini considered himself a poet, painter, philosopher, and political journalist before a film director, as all of his films are built of images, expressions and words that sometimes function more as language than as dialogue. While his work remains controversial to this day, Pasolini has come to be valued by many as a visionary thinker and a major figure in Italian literature and art. He had directed about 25 films and also contributed to the screenplays of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and Nights of Cabiria, before unfortunately being murdered on the beach at Ostia, near Rome in 1975. When originally released The Gospel According to St. Matthew won the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Festival, but the Right-wing Catholic groups picketed it. The film won the first prize of the International Catholic Office of the Cinema, which screened the film inside Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris; but the French left was as outraged as the Italian right, and Sartre met with Pasolini, telling him somewhat obscurely, “Stalin rehabilitated Ivan the Terrible; Christ is not yet rehabilitated by Marxists.” To view The Gospel According to St. Matthew is to understand that there is no ‘one version’ of the story, and like all great art, the life and death of Christ is a classic story that can be interpreted and explored by several different people, from several different faiths, throughout all different parts of the world.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Gospel According to St. Matthew 1964″ num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Only Pier Paolo Pasolini, an artist who was an atheist, a Marxist, and a homosexual could have made such an authentic and effective film on the life and death of Jesus Christ. Perhaps it was because the story was adapted by a nonbeliever who did not preach, glorify, sentimentalize or romanticize the famous story; and instead did his best to simply record it. According to Barth David Schwartz’s book Pasolini Requiem the impetus for the film took place in 1962. Pasolini had accepted Pope John XXIII’s invitation for a new dialogue with non-Catholic artists, and subsequently visited the town of Assisi to attend a seminar at a Franciscan monastery there. The papal visit caused traffic jams in the town, leaving Pasolini confined to his hotel room; there, he came across a copy of the New Testament. Pasolini read all four Gospels straight through, and he claimed that adapting a film from one of them “threw in the shade all the other ideas for work I had in my head.” The result was his film The Gospel According to St. Matthew which was filmed mostly in the poor, desolate Italian district of Basilicata, and its capital city, Matera. (Mel Gibson would film The Passion of the Christ on the very same locations forty years later.) Unlike previous cinematic depictions of Jesus’ life, Pasolini’s film does not embellish the biblical account with any literary or dramatic inventions, nor does it present an amalgam of the four Gospels. Pasolini stated that he decided to remake the Gospel by analogy and the film’s sparse dialogue all comes directly from the Gospel of Matthew, as Pasolini felt that “images could never reach the poetic heights of the text.” He reportedly chose Matthew’s Gospel over the others because he had decided that “John was too mystical, Mark too vulgar, and Luke too sentimental.” Pasolini’s Christ is played by Enrique Irazoqui, a Spanish economics student who had never acted before, and simply arrived to talk to Pasolini about his work. For his other roles, Pasolini cast local peasants, shopkeepers, factory workers, truck drivers, and for the role of Mary at the time of the Crucifixion, Pasolini casted his own mother. The shooting of non-actors, on real locations followed the style of the Italian Neorealist movement, which was a style that attempted to give a new degree of realism to the cinema. This was certainly the case with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, which chronicles the life of Christ as if a documentarian on a low budget had been following him from birth. First and foremost [fsbProduct product_id=’772′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Pasolini considered himself a poet, painter, philosopher, and political journalist before a film director, as all of his films are built of images, expressions and words that sometimes function more as language than as dialogue. While his work remains controversial to this day, Pasolini has come to be valued by many as a visionary thinker and a major figure in Italian literature and art. He had directed about 25 films and also contributed to the screenplays of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and Nights of Cabiria, before unfortunately being murdered on the beach at Ostia, near Rome in 1975. When originally released The Gospel According to St. Matthew won the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Festival, but the Right-wing Catholic groups picketed it. The film won the first prize of the International Catholic Office of the Cinema, which screened the film inside Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris; but the French left was as outraged as the Italian right, and Sartre met with Pasolini, telling him somewhat obscurely, “Stalin rehabilitated Ivan the Terrible; Christ is not yet rehabilitated by Marxists.” To view The Gospel According to St. Matthew is to understand that there is no ‘one version’ of the story, and like all great art, the life and death of Christ is a classic story that can be interpreted and explored by several different people, from several different faiths, throughout all different parts of the world.

PLOT/NOTES

In Palestine during the Roman Empire, Jesus Christ of Nazareth is born and travels around the country with his disciples creating miracles and preaching to the people about God and salvation of their souls. He is the son of God and the prophesized messiah, but not everyone believes his tale. He is arrested by the Romans and crucified. He rises from the dead after three days.

NEOREALISM

Italian Neorealism came about as World War II ended and Benito Mussolini’s government fell, causing the Italian film industry to lose its center. Neorealism was a sign of cultural change and social progress in Italy. Its films presented contemporary stories and ideas, and were often shot in the streets because the film studios had been damaged significantly during the war.

The neorealist style was developed by a circle of film critics that revolved around the magazine Cinema, including Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini, Giuseppe De Santis and Pietro Ingrao. Largely prevented from writing about politics (the editor-in-chief of the magazine was Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito Mussolini), the critics attacked the white telephone films that dominated the industry at the time. As a counter to the popular mainstream films, including the so-called “White Telephone” films, some critics felt that Italian cinema should turn to the realist writers from the turn of 20th century.

Both Antonioni and Visconti had worked closely with Jean Renoir. In addition, many of the filmmakers involved in neorealism developed their skills working on calligraphist films (though the short-lived movement was markedly different from neorealism). In the Spring of 1945, Mussolini was executed and Italy was liberated from German occupation. This period, known as the “Italian Spring,” was a break from old ways and an entrance to a more realistic approach when making films. Italian cinema went from utilizing elaborate studio sets to shooting on location in the countryside and city streets in the realist style.

The first neorealist film is generally thought to be Ossessione by Luchino Visconti in 1943. Neorealism became famous globally in 1946 with Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, when it won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival as the first major film produced in Italy after the war.

Most neorealism films are generally filmed with nonprofessional actors–although, in a number of cases, well known actors were cast in leading roles, playing strongly against their normal character types in front of a background populated by local people rather than extras brought in for the film.

They are shot almost exclusively on location, mostly in run-down cities as well as rural areas due to its forming during the post-war era, no longer being constrained to studio sets. The topic involves the idea of what it is like to live among the poor and the lower working class. The focus is on a simple social order of survival in rural, everyday life. Performances are mostly constructed from scenes of people performing fairly mundane and quotidian activities, devoid of the self-consciousness that amateur acting usually entails. Neorealist films often feature children in major roles, though their characters are frequently more observational than participatory.

Open City established several of the principles of neorealism, depicting clearly the struggle of normal Italian people to live from day to day under the extraordinary difficulties of the German occupation of Rome, consciously doing what they can to resist the occupation. The children play a key role in this, and their presence at the end of the film is indicative of their role in neorealism as a whole: as observers of the difficulties of today who hold the key to the future.

Many of the films involved Post-synch sound/dubbing employing conversational speech, and local dialects. They also included funtional rather than ostentatious editing that would draw attention to itself, as shots were organized loosely. Many neorealism films involved stories that were episodic, elliptical, or organic in structure. Plot were preferable not a tight framework of cause and effect, but a more fluid relationship between scenes which approximated how events would occur in real life.

Many of the films had a sense of a documentary impulse & immediacy in filming, shifting away from the pretense of studio stories. It wanted to be a cinema that attended to the details and trials of everyday life, of the material experience of average people in difficult situations. It also had a concern with the lives of working-class people and a social commitment and humanist point of view to contemporary stories that spoke to the historical present. Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 film Bicycle Thieves is also representative of the genre, with non-professional actors, and a story of a ‘everyday man’ and his hardships of working-class life after the war.

Italian Neorealism rapidly declined in the early 1950s. Liberal and socialist parties were having a hard time presenting their message. Levels of income were gradually starting to rise and the first positive effects of the Ricostruzione period began to show. As a consequence, most Italians favored the optimism shown in many American movies of the time. The vision of the existing poverty and despair, presented by the neorealist films, was demoralizing a nation anxious for prosperity and change. The views of the postwar Italian government of the time were also far from positive, and the remark of Giulio Andreotti, who was then a vice-minister in the De Gasperi cabinet, characterized the official view of the movement: Neorealism is “dirty laundry that shouldn’t be washed and hung to dry in the open.”

Italy’s move from individual concern with neorealism to the tragic frailty of the human condition can be seen through Federico Fellini’s films. His early works Il bidone and La Strada are transitional movies. The larger social concerns of humanity, treated by neorealists, gave way to the exploration of individuals. Their needs, their alienation from society and their tragic failure to communicate became the main focal point in the Italian films to follow in the 1960s. Similarly, Antonioni’s Red Desert and Blow-up take the neo-realist trappings and internalize them in the suffering and search for knowledge brought out by Italy’s post-war economic and political climate.

Neorealism screenwriter Cesare Zavattini said, “film should address not ‘historical man’ but the ‘man without a label.’ I dare to think that other peoples, even after the war, have what they continued to consider man as a historical subject, as historical material with determined almost inevitable actions…For them everything continued, for us, everything began. For them the war had been just another war, for us, it had been the last war…The reality of buried under the myths slowly reflowered. the cinema began its creation of the world. Here was a tree, here, an old man, here, a house, here a man eating, sleeping, a man crying…The cinema should accept unconditionally, what is contemporary. Today, today, today.”

French film critic Andre Bazin on neorealism: “No more actors, no more story, no more sets, which is to say that the perfect aesthetic illusion of reality, there is no more cinema.”

In the period from 1944–1950, many neorealist filmmakers drifted away from pure neorealism and into a period of “rosy neorealism” of Italian films of the 1950’s. Some directors explored allegorical fantasy, such as de Sica’s Miracle in Milan, and historical spectacle, like Senso by Visconti. This was also the time period when a more upbeat neorealism emerged, which produced films that melded working-class characters with 1930s-style populist comedy, as seen in de Sica’s Umberto D.

There are different debates on when the Neorealist period began and ended. Some claimed it ended in 1948, with the shift in power from the left to the centrist Christian Democrat Party and with the inclusion of Italy in the Marshall Plan, which began to subsidize the film industry once more. Many claimed that the cycle ended with De Sica’s Umberto D in 1952.

Robert Kolker suggests a useful way of thinking about “two Neorealisms. 1) on the one hand a group of films made between 1945 & 1955, and 2) on the other Neorealism as an idea, an aesthetic, a politics…both a form of praxis and an ideal to aspire to.”

Irrelevant Actions were an aesthetic that neorealism provided. Andre Bazin essay on Umberto D saying, “the most beautiful sequence in the film, the awaking of the little maid, rigorously avoids and dramatic italicizing. The young girl gets up, comes and goes in the kitchen, hunts down ants, grinds the coffee…and all these ‘irrelevant’ actions are reported to us with meticulous temporal continuity.”

More contemporary theorists of Italian Neorealism characterize it less as a consistent set of stylistic characteristics and more as the relationship between film practice and the social reality of post-war Italy. Millicent Marcus delineates the lack of consistent film styles of Neorealist film. Peter Brunette and Marcia Landy both deconstruct the use of reworked cinematic forms in Rossellini’s Open City. Using psychoanalysis, Vincent Rocchi characterizes neorealist film as consistently engendering the structure of anxiety into the structure of the plot itself.

-Wikipedia

PRODUCTION NOTES

In 1963, Pier Paolo Pasolini had depicted the life of Christ in his short film La ricotta, included in the omnibus film RoGoPaG, which lead to controversy and a jail sentence for the allegedly blasphemous and obscene content in the film. According to Barth David Schwartz’s book Pasolini Requiem (1992), the impetus for the film took place in 1962. Pasolini had accepted Pope John XXIII’s invitation for a new dialogue with non-Catholic artists, and subsequently visited the town of Assisi to attend a seminar at a Franciscan monastery there. The papal visit caused traffic jams in the town, leaving Pasolini confined to his hotel room; there, he came across a copy of the New Testament. Pasolini read all four Gospels straight through, and he claimed that adapting a film from one of them “threw in the shade all the other ideas for work I had in my head.” Unlike previous cinematic depictions of Jesus’ life, Pasolini’s film does not embellish the biblical account with any literary or dramatic inventions, nor does it present an amalgam of the four Gospels (subsequent films which would adhere as closely as possible to one Gospel account are 1979’s Jesus, based on the Gospel of Luke, and 2003’s The Gospel of John). Pasolini stated that he decided to “remake the Gospel by analogy” and the film’s sparse dialogue all comes directly from the Bible.

Given Pasolini’s well-known reputation as an atheist, a homosexual, and a Marxist, the reverential nature of his film was surprising, especially after the controversy of La ricotta. At a press conference in 1966, Pasolini was asked why he, an unbeliever, had made a film which dealt with religious themes; his response was, “If you know that I am an unbeliever, then you know me better than I do myself. I may be an unbeliever, but I am an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for a belief.” The film begins with an announcement that it is “dedicato alla cara, lieta, familiare memoria di Giovanni XXIII” (“dedicated to the dear, joyous, familiar memory of Pope John XXIII”), as John XXIII was indirectly responsible for the film’s creation, but had died before its completion.

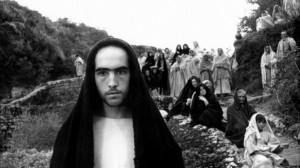

Pasolini employed some of the techniques of Italian neorealism in the making of his film. Most of the actors he hired were non-professionals. Enrique Irazoqui (Jesus) was a 19-year-old economics student from Spain, and the rest of the cast were mainly locals from Barile, Matera, and Massafra, where the film was shot (Pasolini visited the Holy Land but found the locations unsuitable and “commercialized”). Pasolini cast his own mother, Susanna, as the elderly mother of Jesus. The cast also included noted intellectuals such as writers Enzo Siciliano and Alfonso Gatto, poets Natalia Ginzburg and Juan Rodolfo Wilcock, and philosopher Giorgio Agamben. In addition to the original biblical source, Pasolini used references to “2,000 years of Christian painting and sculptures” throughout the film. The look of the characters is also eclectic and, in some cases, anachronistic, resembling artistic depictions of different eras (the costumes of the Roman soldiers and the Pharisees, for example, are influenced by Renaissance art, whereas Jesus has been likened to Byzantine art as well as the work of Expressionist artist Georges Rouault). Pasolini later described the film as “the life of Christ plus 2,000 years of storytelling about the life of Christ.”

Pasolini employed some of the techniques of Italian neorealism in the making of his film. Most of the actors he hired were non-professionals. Enrique Irazoqui (Jesus) was a 19-year-old economics student from Spain, and the rest of the cast were mainly locals from Barile, Matera, and Massafra, where the film was shot (Pasolini visited the Holy Land but found the locations unsuitable and “commercialized”). Pasolini cast his own mother, Susanna, as the elderly mother of Jesus. The cast also included noted intellectuals such as writers Enzo Siciliano and Alfonso Gatto, poets Natalia Ginzburg and Juan Rodolfo Wilcock, and philosopher Giorgio Agamben. In addition to the original biblical source, Pasolini used references to “2,000 years of Christian painting and sculptures” throughout the film. The look of the characters is also eclectic and, in some cases, anachronistic, resembling artistic depictions of different eras (the costumes of the Roman soldiers and the Pharisees, for example, are influenced by Renaissance art, whereas Jesus has been likened to Byzantine art as well as the work of Expressionist artist Georges Rouault). Pasolini later described the film as “the life of Christ plus 2,000 years of storytelling about the life of Christ.”

Pasolini described his experience filming The Gospel According to St. Matthew as much different than his previous films. He stated that while his shooting style on his previous film Accattone was “reverential,” when his shooting style was applied to a biblical source it “came out rhetorical. … And then when I was shooting the baptism scene near Viterbo I threw over all my technical preconceptions. I started using the zoom, I used new camera movements, new frames which were not reverential, but almost documentary combining an almost classical severity with the moments that are almost Godardian, for example in the two trials of Christ shot like “cinema verite.” … The Point is that … I, a non-believer, was telling the story through the eyes of a believer. The mixture at the narrative level produced the mixture stylistically.”

The score of the film is eclectic, ranging from Johann Sebastian Bach (e.g. Mass in B Minor and St Matthew Passion) to Odetta (“Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”) and the “Gloria” from the Congolese Missa Luba. Pasolini stated that all of the film’s music was of a sacred or religious nature from all parts of the world and multiple cultures or belief systems.

The film received mostly good reviews from critics, including several Christian critics. Philip French called it “a noble film,” and Alexander Walker said that “it grips the historical and psychological imagination like no other religious film I have seen. And for all its apparent simplicity, it is visually rich and contains strange, disturbing hints and undertones about Christ and his mission.”

Some Marxist film critics gave the film poor reviews. Oswald Stack criticized the films “abject concessions to reactionary ideology.” In response to criticism from the far left, Pasolini admitted that in his opinion “there are some horrible moments I am ashamed of. … The Miracle of the loaves and the fishes and Christ walking on water are disgusting Pietism.” He also stated that the film was “a reaction against the conformity of Marxism. The mystery of life and death and of suffering — and particularly of religion … is something that Marxists do not want to consider. But these are and have always been questions of great importance for human beings.”

The Gospel According to St. Matthew was ranked number 10 (in 2010) and number 7 (in 2011) in the Arts and Faith website’s Top 100 Films, also is in the Vatican’s list of 45 great films.

The film currently has an approval rating of 94% on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, as legendary critic Roger Ebert added it to his ‘Great Movies’ list. At the 1964 Venice Film Festival, The Gospel According to St. Matthew was screened in competition for the Golden Lion, and won the OCIC Award and the Special Jury Prize. At the film’s premiere, a crowd gathered to boo Pasolini but cheered him after the film was over. The film later won the Grand Prize at the International Catholic Film Office.

The Gospel According to St. Matthew was released in the United States in 1966 and was nominated for three Academy Awards: Art Direction (Luigi Scaccianoce), Costume Design (Danilo Donati), and Score.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

Only Pier Paolo Pasolini, an artist who was an atheist, a Marxist, and a homosexual could have made such an authentic and effective film on the life and death of Jesus Christ. Perhaps it was because the story was adapted by a nonbeliever who did not preach, glorify, sentimentalize or romanticize the famous story; and instead did his best to simply record it. According to Barth David Schwartz’s book Pasolini Requiem the impetus for the film took place in 1962. Pasolini had accepted Pope John XXIII’s invitation for a new dialogue with non-Catholic artists, and subsequently visited the town of Assisi to attend a seminar at a Franciscan monastery there. The papal visit caused traffic jams in the town, leaving Pasolini confined to his hotel room; there, he came across a copy of the New Testament. Pasolini read all four Gospels straight through, and he claimed that adapting a film from one of them “threw in the shade all the other ideas for work I had in my head.” Unlike previous cinematic depictions of Jesus’ life, Pasolini’s film does not embellish the biblical account with any literary or dramatic inventions, nor does it present an amalgam of the four Gospels. Pasolini stated that he decided to remake the Gospel by analogy and the film’s sparse dialogue all comes directly from the Gospel of Matthew, as Pasolini felt that “images could never reach the poetic heights of the text.” He reportedly chose Matthew’s Gospel over the others because he had decided that “John was too mystical, Mark too vulgar, and Luke too sentimental.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew is one of the most powerful and complex films that explore the life and death of Jesus Christ. The shooting was mostly in the poor, desolate Italian district of Basilicata, and its capital city, Matera which were the very same locations director Mel Gibson would film The Passion of the Christ forty years later. The film was created following the style of the Italian Neorealist movement, which was a style that attempted to give a new degree of realism to the cinema. Neorealism, as a term, can mean several things; it often refers to films of working class life and of the struggles and social conditions of people set in the culture of poverty. Italian Neorealism was a revolutionary breakthrough, not just for its technical style and raw film-making, but for the gritty realism of its story and poignant naturalism of its characters. The aesthetics of Neorealism included films that were mostly shot on a very low-budget and on real locations not using any stages or props. It was also a style which casted non professional actors because it brought a sense of reality to the characters, where the acting seemed more natural and real. After decades of Hollywood gloss, real people instead of actors were startling to audiences. This was certainly the case with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, which chronicles the life of Christ as if a documentarian on a low budget had been following him from birth. Neorealism’s gritty, low-budget and provocative style not only set the perfect tone for the bleak landscape to tell Jesus story, but the stark urban images projects a powerful understanding of its place and time within Post World War II history.

Pasolini’s Christ was played by Enrique Irazoqui, a Spanish economics student who had never acted before, and simply arrived to talk to Pasolini about his work. Schwartz quoted Pasolini: “Even before we had started talking, I said ‘Excuse me, but would you act in one of my films’?” Schwartz describes Irazoqui as the “son of a Basque father and a Jewish mother…thin, stoop-shouldered, heavy-browed, anything but the muscular Christ of Michelangelo.” For his other roles, Pasolini cast local peasants, shopkeepers, factory workers, truck drivers, and for the role of Mary at the time of the Crucifixion, Pasolini casted his own mother. The portrayal of Jesus that Pasolini gives us is much different from all the other portrayals of Jesus in the past. This version of Jesus wears his hair short, is unshaven but not bearded, and most of the time he is under a hooded robe so that his face is often hidden in the shadows. No glowing white aura exudes from his robes, and no angelic halo floats above his head. Even his attire is ragged, not white and pure like many Jesus figures, but rough and awful like the peasants he visits; a characteristic that shows Jesus is one like his people. Pasolini’s Jesus is a much more aggressive figure in tone and spirit, and when he preaches his word he always tends to shout, claiming not necessarily that he is bringing peace to his people, but instead a sword. All the dialogue that is used throughout the film is used from the book of Matthew, and much of Jesus’ preaching is heard through several long shots where it is quite difficult to see his lips moving. His personal style is sometimes gentle, as during the Sermon on the Mount, or debating with the elders in the temple, but more often he speaks with a righteous anger, like a union organizer or a war protester. The fact that Pasolini shows Jesus more as a avant-garde teacher and does not focus as much on the miraculous elements of scripture, makes the reactions of his followers much more personal than many other Jesus films.

Presented in an almost-documentary style, the depiction of Jesus can be looked at as more a close reflection on the director’s own self-image, more as a revolutionary and an outsider as opposed to the typical mysticism that is usually found in modern TV biblical adaptations. The film also embodies the spirit of a Catholic-Marxist world, making this version of the life of Jesus one of most artistic and certainly the most audacious. The film is cinematically interesting being one of the first religious films to portray the life and death of Jesus in a gritty realistic sense, focusing on the authenticity of the content instead of the more fantastical elements that are usually thrown in other adaptations. This style is something very different from what modern audiences are used to seeing and it serves a great purpose in this film. Being shadowed by Marxist ideas, a concept based on class structure and power struggles, a problem synonymous with the people in the time of scripture, an idea of reality is important. The film is noted for its sense of newsreel like realism, and this style brings that to life on a more fundamental level below its attention to scripture and theological relevance.

Aesthetically, the score is brilliantly powerful and perfectly controlled to help establish the mood in particular sequences. The heavy beat found during scenes of public praise creates an atmosphere of excitement; while the mellow Bach score under the scene of Peter realizing he denied Jesus three times fills a visually basic scene with an aching intensity. The relationship between the diagetic sound and silence is what sets the mood of the entire film. Other small directorial choices work in the film to further Jesus’ ideas and humanity, such as Jesus smiling only when curious children are around, and the well-lit way women are often shot, and rarely speak, as if to be icons of purity.

The movie is quite literally sensitive to the gospel sources. Being a film, it of course has to omit particular scenes for cinematic purposes, but the ones Pasolini chose to omit, he chose well. The parts of the gospel story that remain in the film are the most identifiable by audiences, as well as the most helpful in portraying Jesus in the way he was meant to be seen in the film. Pasolini focused on the human elements of Jesus, and his omissions help further that image. Scripture is used carefully, and the Jesus character very seldom quotes parable. However, the structure and path of the gospel sources found in the film are loyal to the path of the text. Pasolini’s only real difference from gospel comes in its presentation, which goes back to his method of portrayal. For example, his image of the angel appearing as a person, not through dreams but as a physical being, is an avoidance of divinity that concentrates on his own image of Jesus the human. The fact that Pasolini used all amateur actors for the roles of his disciples was almost literally satisfying decision in itself, as Jesus chose the twelve apostles seemingly at random as well.

Among concepts that were omitted are Jesus’ genealogy, the transfiguration scene, and apocalyptic prophecy. But these things either would have been unnecessary for the story, or were omitted to keep with Jesus’ image. The important aspect in adapting scripture is not so much taking things out, because that obviously needs done, but the fact that nothing fictional is added. And that is what Pasolini is best at when it comes to the literary translation. He respectfully sticks to gospel, only removing unnecessary scenes, adding nothing.

The Gospel According to St. Matthew perfectly sums up the theology by being honest and sincere to the text, while showing Jesus in a light unique to many other films. Pasolini clearly used the Jesus story to not only humanize a person so often identified by mysterious divinity, but to elicit a social commentary of his own ideas and motifs. There are a few historical improbabilities depicted in the film, but even they are sensitive to the gospel text. Historical improbabilities exist throughout the Bible. The film does a great job at accurately representing the bible text, and therefore these literal improbabilities become improbabilities in the film as well. For example, Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey on Palm Sunday, among audiences of people laying the path with cloths is not something that would have happened during that time. However, this scene is described in scripture very similarly to how Pasolini showed it on film, making its improbability not unique to the film. Additionally, early films such as this one, and modern films alike, have always enjoyed showing Jesus carrying the full cross on his back while walking up the mountain to be crucified. The gospel of Matthew does not say whether or not Jesus was carrying the entire cross, and it is likely that he wouldn’t have been, and therefore is an inaccuracy that exists in an incredible amount of film, artwork and writing. The gospel does say the cross was being carried, but what amount of it is not specified. A third improbability is Jesus’ removal from the cross after crucifixion. It was not custom to ever remove a body from a cross, rather they were just left to hang until the body was picked over by nature. The removal of Jesus has been questioned for some time – yet the scripture says it is done, so that is another inaccuracy in both text and film, not unique to Pasolini’s movie.

The film shot in black and white, is told with stark simplicity. The opening scene we see Mary in closeup. We then see Joseph in closeup. We see Mary in long shot, and that she is pregnant. We see Joseph regarding this fact. The film later follows Joseph as he leaves his home and falls asleep against a boulder. He is suddenly awakened by an angel who takes the form of a normal peasant girl. The angel tells him that Mary will bear the son of God, but the angel later warns them to flee to Egypt before Herod orders the killing of the first-born.

The massacre of the babies is a brief scene, and seems more disturbing because Pasolini does not show explicit closeups of the violence. The miracles that are shown in the film are extremely low-key and subtle and don’t draw much attention to themselves, which make the miracles all the more effective. For instance, the cure of a leper with a large tumor on his face first shows the leper walk up to Jesus begging for his help. The shot cuts to Jesus and quickly back to the leper whose tumor has now miraculously disappeared. The miracles of the loaves and fishes and the walking on the water are treated in a much similar fashion. Christ tells his disciples to depart in their boat, and without any fancy camera effects, heightened dramatic music, or the waving of hands, Pasolini quite simply just shows a figure walking on water.

First and foremost director Pier Paolo Pasolini considered himself a poet, painter, philosopher, and political journalist before a film director, as all of his films are built of images, expressions and words that sometimes function more as language than as dialogue. While his work remains controversial to this day, Pasolini has come to be valued by many as a visionary thinker and a major figure in Italian literature and art. He had directed about 25 films and also contributed to the screenplays of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and Nights of Cabiria. Mama Roma was one of Pasolini’s great earlier neo realism film, which tells the story of a middle-aged whore in Rome (played by the great Italian actress Anna Magnani) trying to win back her only son. Besides The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Pasolini is mostly known for his last film Salo: 120 Days of Sodom which presents Four fascist libertines who round up 9 teenage boys and girls and subject them to 120 days of physical, mental and sexual torture. Salo: 120 Days of Sodom not only was considered one of the most disturbing and depraved films ever made, but it generated so much controversy that Pasolini was brutally murdered before its release while on the beach at Ostia, near Rome in 1975.

Unfortunately many people today look at Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ as the definitive movie on the life and death of Jesus. The trial of Jesus in The Gospel According to St. Matthew, as in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ places much of the blame on the Jewish high priests, as Matthew does, but the large difference in Pasolini’s version is that the high priests seem to be less hateful and spiteful, and are also much less anti-Semitic in tone. I always respected Gibson’s bold approach on the material without shying a way from the realistic violence and torture that Jesus had endured, but in many ways I believe that he focused too much on it. The crucifixion in Pasolini’s version brings equally the same amount of raw emotion and power into each sequence as the Gibson version brings. Pasolini’s version is not anymore softened or dramatized in the style of Hollywood biblical epics, but the director decides to rely on the power of words and not simply on the power of violence. Jesus was a man of extraordinary wisdom, and I believe the power of his story is more on the inspirational speeches he made to his people and not simply on the torture of his crucifixion. By having Gibson rely simply on his torture and to ignore the inspirational words that this great man had spoken of seems to slightly cheapen his film to the likes of mere torture porn, with the heightened violence and gore being somewhat exploited by senseless sensationalism. Surely, many of those violent sequences would have been just as equally as powerful or even more so if Gibson simply alluded or suggested them. And yet Gibson clearly had a different intent than Pasolini did with the story, and for him to change it would be for him to change his artistic intentions. (Pasolini would go on to do Salo: 120 Days of Sodom several years later anyway which would be a film that would push the boundaries on violence, torture and gore, and its themes of exploited violence can be looked at as much more sensational and unnecessarily than all of Gibson’s films put together.) To view The Gospel According to St. Matthew is to understand that there is no ‘one version’ of the story, and like all great art, the life and death of Christ is a classic story that can be interpreted and explored by several different people, from several different faiths, throughout all different parts of the world.

Unfortunately many people today look at Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ as the definitive movie on the life and death of Jesus. The trial of Jesus in The Gospel According to St. Matthew, as in Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ places much of the blame on the Jewish high priests, as Matthew does, but the large difference in Pasolini’s version is that the high priests seem to be less hateful and spiteful, and are also much less anti-Semitic in tone. I always respected Gibson’s bold approach on the material without shying a way from the realistic violence and torture that Jesus had endured, but in many ways I believe that he focused too much on it. The crucifixion in Pasolini’s version brings equally the same amount of raw emotion and power into each sequence as the Gibson version brings. Pasolini’s version is not anymore softened or dramatized in the style of Hollywood biblical epics, but the director decides to rely on the power of words and not simply on the power of violence. Jesus was a man of extraordinary wisdom, and I believe the power of his story is more on the inspirational speeches he made to his people and not simply on the torture of his crucifixion. By having Gibson rely simply on his torture and to ignore the inspirational words that this great man had spoken of seems to slightly cheapen his film to the likes of mere torture porn, with the heightened violence and gore being somewhat exploited by senseless sensationalism. Surely, many of those violent sequences would have been just as equally as powerful or even more so if Gibson simply alluded or suggested them. And yet Gibson clearly had a different intent than Pasolini did with the story, and for him to change it would be for him to change his artistic intentions. (Pasolini would go on to do Salo: 120 Days of Sodom several years later anyway which would be a film that would push the boundaries on violence, torture and gore, and its themes of exploited violence can be looked at as much more sensational and unnecessarily than all of Gibson’s films put together.) To view The Gospel According to St. Matthew is to understand that there is no ‘one version’ of the story, and like all great art, the life and death of Christ is a classic story that can be interpreted and explored by several different people, from several different faiths, throughout all different parts of the world.