Contempt (1963)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Contempt Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Jean-Luc Godard’s poetic masterpiece Contempt is a like a haunting three-act Greek tragedy, in which a French playwright gets hired by a seedy and corrupt American film producer to rewrite a movie script of a direct to film adaptation of The Odyssey, which is being directed by the legendary German director Fritz Lang (playing himself). When the producer is told that in 1933 Goebbel asked Lang to be head of the German film industry, and that very same night Lang fled to America, the producer says, “But that was ’33, this is ’63…and he will direct whatever was written, just as I know you are going to write it.” Through a series of misunderstandings between husband and wife, Camille believes her husband is selling out his writing talents, all the while allowing the all powerful and predatory producer to flirt with her; which is what begins the slow deterioration of their marriage. Contempt exists as a string of metaphors, connecting its historical layers of art imitating life, which include Prokosch’s red Alfa Romeo which sweeps in like Zeus’ chariot; Prokosch hurling a film canister in disgust imitating a Greek discus thrower, the bath towel being worn suggesting a Roman toga; and the classic opening sequence in which the CinemaScope camera (Which Lang proudly hates) tilts down to look at the audience, similar to a one-eyed Polyphemus. The tension between artist and corporatism run parallel to Godard and the problems he had with his producers, especially when viewing a early rough cut of the film in which there was not one nude scene of actress Brigitte Bardot. Godard says, “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?” Besides Fritz Lang (who Godard idolized) everyone on the set seemed to be extremely miserable especially actor Jack Palance because of Godard refusing to consider any of his ideas, which led Palance to call his agent in America trying to have him get him off the picture. [fsbProduct product_id=’753′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Contempt can be looked at as a form of apology as cinematographer Raoul Coutard calls the film Godard’s “love letter to his wife,” because of them not getting along during the shooting, and at one point in the film Godard seems to dress Bardot to resemble her, as Bardot dons a black wig which closely resembles the iconic hair-style of Anna Karina. (Is it mere coincidence that Godard originally wanted Kim Novak for the role, the actress who starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, who was also a character who suffered in being molded and formed to resemble the woman of the director’s dreams?) Raoul Coutard’s gorgeous cinematography and lush primary colors add to the films poetic grandeur, but its the masterful soundtrack by George Delerue that really sets the tone for the entire film. The score gives Contempt its full haunting effect as it has a tragic and sad underlining to the music that really represents the tragic relationship that is slowly unfolding. Contempt is one of the greatest meditations on self-criticism and of the creative process of movie-making in which the gods of male artists analyze their self vanities and sexism while the women in their lives are destroyed in the process.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Contempt Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Jean-Luc Godard’s poetic masterpiece Contempt is a like a haunting three-act Greek tragedy, in which a French playwright gets hired by a seedy and corrupt American film producer to rewrite a movie script of a direct to film adaptation of The Odyssey, which is being directed by the legendary German director Fritz Lang (playing himself). When the producer is told that in 1933 Goebbel asked Lang to be head of the German film industry, and that very same night Lang fled to America, the producer says, “But that was ’33, this is ’63…and he will direct whatever was written, just as I know you are going to write it.” Through a series of misunderstandings between husband and wife, Camille believes her husband is selling out his writing talents, all the while allowing the all powerful and predatory producer to flirt with her; which is what begins the slow deterioration of their marriage. Contempt exists as a string of metaphors, connecting its historical layers of art imitating life, which include Prokosch’s red Alfa Romeo which sweeps in like Zeus’ chariot; Prokosch hurling a film canister in disgust imitating a Greek discus thrower, the bath towel being worn suggesting a Roman toga; and the classic opening sequence in which the CinemaScope camera (Which Lang proudly hates) tilts down to look at the audience, similar to a one-eyed Polyphemus. The tension between artist and corporatism run parallel to Godard and the problems he had with his producers, especially when viewing a early rough cut of the film in which there was not one nude scene of actress Brigitte Bardot. Godard says, “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?” Besides Fritz Lang (who Godard idolized) everyone on the set seemed to be extremely miserable especially actor Jack Palance because of Godard refusing to consider any of his ideas, which led Palance to call his agent in America trying to have him get him off the picture. [fsbProduct product_id=’753′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Contempt can be looked at as a form of apology as cinematographer Raoul Coutard calls the film Godard’s “love letter to his wife,” because of them not getting along during the shooting, and at one point in the film Godard seems to dress Bardot to resemble her, as Bardot dons a black wig which closely resembles the iconic hair-style of Anna Karina. (Is it mere coincidence that Godard originally wanted Kim Novak for the role, the actress who starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, who was also a character who suffered in being molded and formed to resemble the woman of the director’s dreams?) Raoul Coutard’s gorgeous cinematography and lush primary colors add to the films poetic grandeur, but its the masterful soundtrack by George Delerue that really sets the tone for the entire film. The score gives Contempt its full haunting effect as it has a tragic and sad underlining to the music that really represents the tragic relationship that is slowly unfolding. Contempt is one of the greatest meditations on self-criticism and of the creative process of movie-making in which the gods of male artists analyze their self vanities and sexism while the women in their lives are destroyed in the process.

PLOT/NOTES

From the words of Andre Bazin: “The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires. Contempt is a story of that world.”

As you hear the narrator you see a cameraman filming a scene of the character of Francesca on the Cinecittà studios slowly across a dolly. The camera turns and then dollies up and pivots looking straight towards the camera.

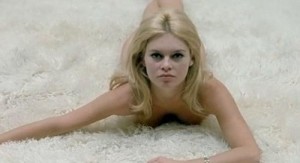

The opening sequence goes directly inside writer Paul Javal’s (Michel Piccoli) apartment as he’s in bed with his beautiful wife Camille Javal (Brigitte Bardot). The films color tone is completely red as it shifts back and forth to several different color filters while Camille is laying completely nude face down, asking her husband if her body parts are beautiful. “See my feet in the mirror? Think they’re pretty? You like my ankles? And my knees too? And my thighs? See my behind in the mirror? Do you think I have a cute ass? And my breasts. You like them? Which do you like better, my breasts or my nipples? And my face? All of it? My mouth, my eyes, ,my nose, my ears? Then you love me totally?” Her husband responds by saying, “I love you totally…tenderly…tragically.” Camille talks about seeing her mother tomorrow, and Paul tells her he has to see an American film producer named Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance) about a screenwriting position the next morning so he decides to get some sleep.

That next morning at the Rome’s Cinecittà studios Paul meets Francesca Vanini (Giorgia Moll), Prokosch’s secretary and translator who will help translate English and French since neither Prokosch nor Paul know each other’s language. Paul asks where everyone is because the studio looks so abandoned and Francesca says that Prokosch fired everyone because Italian cinema is in trouble. Suddenly Prokosch comes out of the studio and loudly states, “Only yesterday their were kings here. Kings and Queens, liars and lovers. All kinds of real human beings.” Prokosch is a very dominating, arrogant, egotistical producer who has been very prosperous in the past on making successful pictures. He tells Paul that he is doing a direct film adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey and that he needs a German director, because everyone knows a German discovered Troy.

Prokosch wants Paul to write some new scenes for The Odyssey. He has a “Hercules” style ripoff in mind, but unfortunately his director wants to make an art film, and that’s not what he wants. Paul says that Producers do not know what they want. Prokosch pulls out a little red book and reads: “To know the one that not knows is the gift of the superior spirit. Not to know but think that one does know is a mistake.” says Prokosch. When Paul is told from Francesca that it is Fritz Lang directing Paul says, “In ’33 Goebbel asked Lang to head the German film industry. That night, Lang left Germany.” Prokosch interrupts by saying, “But that was ’33, this is ’63…and he will direct whatever was written, just as I know you are going to write it.”

Paul and Francesca then follow him to the screening room on foot while Prokosch gets in his red Alfa Romeo and drives there. Before they walk into the screening room Paul asks Prokosch why he wants to him to rewrite the film on the and Odyssey Prokosch says its because he knows he needs the money. Prokosch says to Paul, “”Someone told me you have a very beautiful wife,” which is the foreshadowing of Prokosch’s predatory intentions later in the film. When they get into the screening room Fritz Lang (played of course by the great Fritz Lang himself) is already there watching early shots of the rushes which are of full of shots containing several Greek statues and of the actors and actresses swimming in the waters of Capre, Italy in Casa Malaparte.

While watching it Prokosch says, “I like gods. I like them very much. I know exactly how they feel – exactly.” Fritz Lang replies, “Jerry, don’t forget. The gods have not created man. Man has created gods.” When Paul says that he likes CinemaScope, Lang gives a classic responds by saying, “Oh, it wasn’t meant for human beings. Just for snakes – and funerals” (Which is ironic since this film is shot in CinemaScope.) Prokosch is unsatisfied with what is on the screen believing audiences won’t understand it and throws a tantrum by throwing film reels everywhere. “That’s what I think about that stuff up there. You’ve cheated me, Fritz. That’s not what is in that script,” Prokosch says. Fritz says,”It is!” Paul states, “Get the script, Francesca. Yes, it’s in the script. But it’s not what you have on that screen.”Fritz says, “Naturally, because in the script it is written, and on the screen it’s pictures. Motion picture, it’s called.”

When Prokosch throws another film disc in the form of a famous Greek statue Lang says sarcastically, “finally you get the feel of Greek culture.” Prokosch than says, “Whenever I hear the word ‘culture,’ I bring out my checkbook.” Prokosch then writes a check out and gives it to Paul and offers him the job to rewrite the script. Paul accepts and takes the check. Lang again sarcastically responds, “Some years ago – some horrible years ago – the Nazis used to take out a pistol instead of a checkbook.” Lang goes over some Hölderlin’s poetry with Francesca saying, “is no longer about God’s presence. It’s God’s absence that reassures Man.”

After they leave the screening room Paul’s wife arrives right when Prokosch pulls up in his red Alfa Romeo. Paul introduces Camille to Lang telling his wife Lang was the one who did that western with Dietrich. Lang says, “I prefer M.” Camille says that she caught it on TV and really liked it. Camille looks at Prokosch’s flashy red Alf Romeo as he asks her to have a drink at his home. Francesca translates for Camille but she says she doesn’t know. Prokosch opens his passenger door and asks Camille in telling Paul he won’t be comfortable in the back so he’d probably be better if he got a taxi. Paul accepts knowing clearly that Prokosch is interested in his wife and that his wife feels uncomfortable and it hurts Camille that Paul would use her like that; which is the starting point on the collapse of the relationship.

The next shot circles around a Greek statue of Ulysses and in several dramatic points in the film the film will go back to that statue which symbolizes the story of The Odyssey and the parallel of the story of Paul and Camille. When Paul finally shows up late to Prokosch’s home his wife is being very distant with him. When Prokosch asks Paul what took so long Paul looks at his wife and asks what he is saying and Camille says she knows as much English as Paul does. “We’ve been waiting a half hour. What happened?” Paul explains he was in a cab and ran into an accident. Camille is upset and decides to ignore Paul distancing herself from him and says, “Anyway, I don’t give a damn. I’m not interested in your story,” and angrily goes for a walk as Camille flashes back to earlier moments of her and Paul. When Prokosch and Francesca as Paul asks his wife what she was doing before he arrived. Paul them asks, “Why? Did he hit on you,” as Paul slightly snickers which irritates his wife even more. He decides to go into Prokosch home to wash his hands.

When Paul walks into Prokosch’s large extravagant home, he starts to flirt with Francesca by touching her hair, and starts asking about her boss Prokosch but she doesn’t want to talk about it. “It’s a drag to be so cute and so sad,” he tells her. “Haven’t you have anything more amusing to say?” She asks. Paul tries telling Prokosch a joke and even grabs her behind right when Camille walks in. “Call that washing your hands,” Camille asks Paul. Prokosch hands Paul a book of Roman paintings and invites them to stay for dinner but Camille tells her husband she wants to leave. Prokosch says to Francesca, “I want the money and his wife.” Prokosch invites them to the filming of The Odyssey in Capri where Prokosch has a villa. Prokosch asks Camille if she’s coming and Camille turns to Paul and says, “It’s my husband who decides.” Prokosch pulls out his little red book once again and reads: “The wise man does not suppress others with his superiority.”

While leaving through the gates of Prokosch Camille says, “He’s crazy! See that? He kicked her!” Paul says, “You change your mind fast. Monday you though he was terrific.” Walking back to their new apartment Camille says, “Now I think he’s a jerk. I have a right to change my mind.” Paul seems to have taking the job just for the money, (and for the flat that his wife so wanted) and because of that Paul seems to have lost some stature in his wife’s eyes. Paul knows something is upsetting Camille and so he asks her what had happened in the last hour and Camille says, “Nothing. If your happy, I’m happy.” Paul suggest seeing a movie, maybe Rio Bravo or Nicholas Ray’s Bigger than Life, (which Paul says he wrote) but Camille is not interested. To two walk to their new apartment and admire it, knowing Paul is getting six million lire for the script and he can now finish paying off the flat.

Like the bedroom seen in Godard’s Breathless, the thirty minute apartment sequence is one of the most fascinating parts of the film.

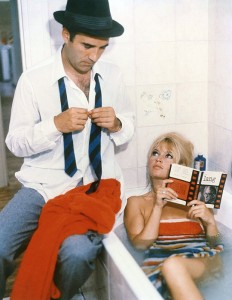

It’s an amazing sequence of ‘real-time’ everyday realism as the camera follows the married couple around the apartment through their casual moves of sitting on the toilet, doing some writing, opening a soda, laying on the couch, taking a bath and talking and walking away in the middle of a sentence. Mostly Paul is trying to have Camille reveal what has been bothering her because she hasn’t been tender towards him since that morning, and now seems to be more colder, contemptuous and distant. Paul asks if she wants them to go to Prokosch’s villa in Capri and she says, “I won’t say no, but I won’t say yes either.” She tells him that Prokosch invited Paul anyways and not her. While Paul is sitting in the tub he tells his wife that they were both invited.

Camille walks into the bathroom wearing a black wig and Paul says that he prefers her as a blond. She says, “And I prefer you without a hat and cigar.” He tells her he is trying to resemble Dean Martin in Some Came Running. Camille tells him that he looks more like Dean Martin’s ass, and when she tries to explain it through a story, Paul doesn’t understand and insults her saying, “You’re a complete idiot, why did I marry a twenty-eight year old typist.” When she continues to be aloof to Paul he asks, “You’ve been acting weird today. What’s wrong?” He asks if it was that girl Francesca and when she calls him an ass again he smacks her. “You frighten me Paul, its not the first time,” she says. “Go to Capri if you want, but I don’t want to.” Camille wraps herself in a hot orange towel and sits on the toilet smoking a cigarette. Paul asks why the thoughtful air and she says, “Maybe because I’m thinking of something. That surprise you?”

When Camille’s mother calls Paul answers and questions her if Camille really went out to eat with her earlier. He then lies and says Camille isn’t there and when Camille catches him she is furious. After getting off the phone with her mother Camille says, “You’re out of your mind old man. Try that again and I’ll divorce you.” Camille is angry knowing he was questioning her mother to see if Camille really went out to eat with her the other day. Camille grabs the bed-sheets and says she will be sleeping on the couch from now on, saying the draft from the open window keeps her awake. “Your so mean all of a sudden,” Paul says. Camille tells Paul that he is the one that has changed saying, “Ever since you’ve been with movie people. You used to write crime novels. We didn’t have much money, but everything was fine.”

“I’m working for you!” Paul yells. “This place is for you, not just for me.” Paul scans through the Greek mythology book that Prokosch gave him and tells his wife he isn’t going to the Capri. He tells her he took this job out of love for her but now she doesn’t love him anymore. “Something makes you think I’ve stopped loving you?” She asked. Paul says it was the way she has been talking to him. Camille has now moved to the bath as she is reading a book on Fritz Lang and Paul sits on the edge of the bath and says, “It’s the way you look at me, too.” Camille peers up over the book she is reading to look at Paul. Camille starts to read passages of the book out-loud and Paul asked why she is going to start sleeping on the couch knowing her saying that the window open keeps her awake isn’t the real reason.

“I want to sleep alone from now on.”

“You don’t want to make love?”

“Listen to the jerk.”

“Is that a mocking smile or tender smile.”

“Tender smile.”

“So, answer me!”

“If it were true, I’d tell you. A woman can always find an excuse not to make love.But you’re a jerk.”

“Vulgar language doesn’t suit you.”

“It doesn’t suit me? Listen to this: Asshole. Cunt. Shit. Christ almighty. Craphole. Son of a bitch. Goddamn. So, still think it doesn’t suit me? ”

“Why don’t you want to make love anymore?”

“All right. Let’s do it, but fast.”

The two lovers narrate their own personal thoughts and feelings that they are not honesty telling one another with repeats in dialogue and flashbacks and flash-forwards of the story.

“I’d been thinking Camille could leave me. I thought of it as a possible disaster. Now the disaster has happened.”

“We used to live in a cloud of unawareness, in delicious complicity. Things happened with sudden, wild, enchanted recklessness. I’d end up in Paul’s arms, hardly aware of what had happened. ”

“This recklessness was now absent in Camille, and thus in me. Could I now, prey to my excited senses, observe her coldly, as she could undoubtedly observe me?”

“I deliberately made that remark with a secret feeling of revenge.”

“She seemed aware that a lie could settle things. For a while, at least. She was clearly tempted to lie. But on second thought, she decided not to.”

“Paul hurt me so much. It was my turn now, by referring to what I’d seen, without really being specific.”

“At heart I was wrong. She wasn’t unfaithful or she only seemed to be. The truth remained to be proven despite appearances.“I’ve noticed the more we doubt, the more we cling to a false lucidity, in the hope of rationalizing what have made murky.”

They eventually forgive each other for a short period with Camille reassuring Paul that she does indeed still love him and he should continue with this movie script job. That is until Paul gets a phone call and they are both supposed to meet Prokosch and Lang at a movie theater where they want to see a singer in the show. Things get to a darker point as Paul says that going to this show might give him ideas and Camille criticizes his work by saying “Why not look for ideas in your head, instead of stealing them?” Paul says, “Since I said yes to Prokosch, so long tenderness!” Camilla says, “Right, no more caresses.” Paul asks if there is something between her and Prokosch and Camille says he is pathetic. Paul believes she lied shortly ago about her love to him just to keep the flat.

The two sit down with a lamp separating the two as the camera pans back and forth and Camille says, “It’s true. I don’t love you anymore. There’s nothing to explain. I don’t love you.” She says that she loved him yesterday but not no more. Paul knows there is a reason and he keeps trying to pry out what the reason is, bringing Francesca up again and of him patting her behind. “Let’s say it was that. Now its over, let’s not talk about it,” Camille says. When he explains his reasoning for her not loving him anymore she says, “You’re crazy, but you’re smart.” When things get physical and she slaps him she starts to leave and says, “I despise you. That’s why loves gone. I despise you. And you disgust me when you touch me.” Paul eventually grabs a stashed revolver before running out and catching a cab with Camille. “Forget what I said, Paul,” she says. “Act as though nothing happened.”

They meet everyone at a auditioning of The Odyssey at the theatre. What I find interesting about this scene is that no one is really interested in any of the actresses performing on the stage and they look extremely bored. Prokosch says that he reread the Odyssey the other night and finally found something he was looking for for a long time, something that is as indispensable to the movies as it is to real life…poetry. Prokosch asks Paul if he remembers what he told him on the phone. Paul says, “They say Ulysses came home to Penelope; but maybe Ulysses had been fed up with Penelope. She went off to the Trojan war and since he didn’t feel like going home, he kept traveling as long as he could.” (Sounds parallel to Paul and Camille current’s predicament.)

As they all walk out Lang says a ballad by Bertolt Brecht, “Each morning, to earn my bread to go to the market where lies are sold, and , hopeful, I get in line with the other seller.”‘ Lang tells Paul about the idea of Odysseus. “Homer’s world is a real world. And the poet belonged to a civilization that grew in harmony, not in opposition with nature. The beauty of the Odyssey lies precisely in this belief in reality as it is.” Prokosch asks Camille why she doesn’t say something. The theater lights go out and you hear her say, “Because I have nothing to say.”

Everyone leaves to head to the location shooting in Capri. When Francesca and Prokosch leave Lang says, “Producers are something I can easily do without.” After Lang leaves Paul says to Camille that they don’t have to go to the Capri and that he’s not forcing her. Camille just replies sadly, “It’s not you that’s forcing me…It’s life.”

The next shot is a beautiful shot of Camille sitting with the blue clear ocean behind her watching the camera men setting up a shot of The Odyssey film. Paul asks his wife why she is sitting all alone, and that he agrees with Prokosch’s theory of The Odyssey saying, “That Ulysses loves his wife, but she doesn’t love him.” Paul watches the actresses get nude for the movie and says, “Aren’t’ movies great! You see women in dresses, in movies you see their asses!” Prokosch asks Camille to come up to the villa with him and leave her husband down their to talk with Lang. Camille asks her husband what she should do (you can see she’s begging for him to not have her go with him) and he tells her to go along with Prokosch.

Capri is beautifully shot in lush primary colors showing the landscapes of the ocean and the islands and there is one extraordinary shot of Paul at the very edge of the frame viewing out at the gorgeous scenery. While Lang and Paul are talking Lang says, “A producer can be a friend to a director. But Prokosch isn’t a real producer. He’s a dictator. Lang doesn’t believe in changing the character of Ulysses, believing he’s not a neurotic but a simple, clever and robust man. Paul believes the character is slightly illogical and that he used the Trojan war to get away from his wife. Paul and Lang debate the dramatic parts characteristics of Ulysses and Penelope’s relationship and to why Penelope had an affair with his suitors causing Ulysses to murder them. After some time, Paul is searching for his wife on Prokosch’s villa and there is an interesting angle of him looking down from the roof catching Camille kissing Prokosch in a window.

Later on inside before dinner Paul starts going off on an angry tangent in front of everyone trying to prove a point to his wife that he isn’t spineless and that he didn’t take the job just for the money; saying how he no longer wants to write the script. “I’m a playwright. Not a screenwriter. Even if its a fine script…I’m being frank. We all have an ideal. Mine’s writing plays. I can’t. Why? In today’s world, we have to accept what others want. Why does money matter so much in what we do, in what we are, in what we become? Even in our relationships with those we love.” Francesca translates it all to Prokosch and Lang and Camilla sit quietly by.

Prokosch becomes angry because of Paul’s remarks and Francesca says to Paul, “You may be right, but when it comes to making movies, dreams aren’t enough.” In his last attempt at trying to save his marriage Paul sacrifices his job which of course greatly angers Prokosch as Prokosch order Lang in that he wants to talk to him alone. Lang responds by asking, “Is that an order or a request?” Before he leaves the room Lang says to Paul, “one has to suffer,” which shows Lang probably had to suffer many of his creative intentions through studios and producers over the years.

Paul later confronts Camille sun tanning on the roof of the villa with a book covering her bottom. Camilla tells Paul that it was foolish of him to quit saying, “I don’t get you! You always said you loved the script.Now you tell the producer that you did it for the money and your ideal’s the theater. He’s no fool. Next time he’ll think twice before asking you.” Camille says that Paul will still take the job because she knows him. Paul says he’ll only take it for her, and to pay for the flat. Paul says he’ll let Camille decide if he does the script or not and he again asks her why she stopped loving him and despises. “I’ll never tell you, even if I was dying,” Camille tells Paul and she begins to walk away and make her way down the steep steps. Camille says that she loved him so much but not anymore as she know looks at him differently.

There’s a really nice shot of her removing yellow her robe off-screen but throwing her robe in the shot of the frame and jumping off-screen into the ocean. Paul is trying his most to make amends pointing out that he knows the taxi situation the other day and earlier on the boat in which he let Camille go off with Prokosch was wrong. She says she will never for forgive him saying, “I hate you because you’re incapable of moving me.’ Paul says that they are going to pack up and leave but his wife ignores Paul and continues to head down near the water. Paul realizes it is now too late to save their relationship. “I don’t love you anymore. There’s no way I’ll ever love you again,” Camille says to him right before she jumps in the water while off-screen. She reappears in the frame swimming in the ocean.

The next scene Camille leaves a letter for Paul that reads: “Dear Paul. I found your revolver and took the bullets out. If you wont leave I will. Since Prokosch has to return to Rome, I’m going with him. Then I’ll probably move in a hotel alone. Take care. Farewell. Camille.” The next sequence shows Camille and Prokosch stopping at a gas station as Camille says to Prokosch (the best she can since either of them know each other’s language) that she will try to find a job as a typist when in Rome, and Prokosch believes she is crazy.

The two get killed suddenly in a fatal car accident (which is shown off-screen) as you just hear the accident while you see the close-up of Camille’s good-bye note to her husband; most importantly the words ‘farewell’ and ‘Camille.’ Paul says good-bye to Francesca and Lang saying he will head back to Rome and finish his play while Lang will finish the film says, “Always finish what you start.” The last shot ends with Fritz Lang filming a sequence of The Odyssey which the scene of Ulysses gaze when he first sees his homeland again, as the camera pans past the film crew and into the ocean as you hear director Fritz Lang yell “silence!” off-screen.

ANALYZE

Contempt, one of Jean-Luc Godard’s greatest masterpieces, has a stately air that breaks with the filmmaker’s earlier, throwaway, hit-and-run manner, as though he were this time allowing himself to aim for cinematic sublimity. It is both his richest study of human relations, and a film very much about a tortured kind of movie love. The film has inspired passionate praise—Sight & Sound critic Colin MacCabe may have gone slightly overboard in dubbing Contempt “the greatest work of art produced in post-war Europe,” but I would say it belongs in the running. It has certainly influenced a generation of filmmakers, including R.W. Fassbinder, Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese (who paid his own homage by quoting from the Godard film’s stark, plangent musical score in Casino, and cosponsoring its re-release). Scorsese has called Contempt “brilliant, romantic and genuinely tragic,” adding that “It’s also one of the greatest films ever made about the actual process of film-making.”

In 1963, film buffs were drooling over the improbable news that Godard—renowned for his hit-and-run, art house bricolages such as Breathless and My Life to Live—was shooting a big CinemaScope color movie with Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance, based on an Alberto Moravia novel, The Ghost at Noon. It sounded almost too good to be true. Then word leaked out that Godard was having problems with his producers, Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine (the distributor of Hercules and other schlock), who were upset that the rough cut was so chaste. Not a single nude scene with B.B.—not even a sexy costume! Godard obliged by adding a prologue of husband and wife (Michel Piccoli and Bardot) in bed, which takes inventory of that sumptuous figure through color filters, while foreshadowing the couple’s fragility: when she asks for reassurance about each part of her body, he reassures her ominously, “I love you totally, tenderly, tragically.”

Beyond that “compromise,” Godard refused to budge, saying: “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?”

Ironically, Contempt itself dealt with a conflict between a European director (Fritz Lang playing himself) and a crude American producer, Jerry Prokosch (performed with animal energy by Palance), over a remake of Homer’s Odyssey. Prokosch hires a French screenwriter, Paul (Michel Piccoli), to rewrite Lang’s script. Paul takes the job partly to buy an apartment for his wife, the lovely Camille (Bardot); but in selling his talents, he loses stature in her eyes. Through a series of partial misunderstandings, Camille also thinks her husband is allowing the powerful, predatory Prokosch to flirt with her—or at least has not sufficiently shielded her from that danger. Piccoli, in the performance that made him a star, registers with every nuance the defensive cockiness of an intellectual-turned-hack who feels himself outmanned.

According to Pascal Aubier, a filmmaker who served as Godard’s assistant on Contempt and many of his other sixties pictures, “It was a very tormented production.” Godard, unused to working on such a large scale, was annoyed at the circus atmosphere generated by the paparazzi who followed Brigitte Bardot to Capri. B.B., then at the height of her celebrity, arrived with her latest boyfriend, actor Sami Frey, which further irritated Godard, who liked to have the full attention of his leading ladies. The filmmaker was also not getting along with his wife (and usual star) Anna Karina, and seemed very lonely on the shoot, remembers Aubier; “but then, that’s not unusual for him. Godard also has a knack for making people around him feel awkward, and then using that to bring out tensions in the script.” He antagonized Jack Palance by refusing to consider the actor’s ideas, giving him only physical instructions: three steps to the left, look up. Palance, miserable, kept phoning his agent in America to get him off the picture. The only one Godard got on well with was Fritz Lang, whom he idolized. But Lang was not feeling well, and had to cut short his participation.

According to Pascal Aubier, a filmmaker who served as Godard’s assistant on Contempt and many of his other sixties pictures, “It was a very tormented production.” Godard, unused to working on such a large scale, was annoyed at the circus atmosphere generated by the paparazzi who followed Brigitte Bardot to Capri. B.B., then at the height of her celebrity, arrived with her latest boyfriend, actor Sami Frey, which further irritated Godard, who liked to have the full attention of his leading ladies. The filmmaker was also not getting along with his wife (and usual star) Anna Karina, and seemed very lonely on the shoot, remembers Aubier; “but then, that’s not unusual for him. Godard also has a knack for making people around him feel awkward, and then using that to bring out tensions in the script.” He antagonized Jack Palance by refusing to consider the actor’s ideas, giving him only physical instructions: three steps to the left, look up. Palance, miserable, kept phoning his agent in America to get him off the picture. The only one Godard got on well with was Fritz Lang, whom he idolized. But Lang was not feeling well, and had to cut short his participation.

No sign of the shooting problems mars the implacable smoothness of the finished product. Godard famously stated that “a movie should have a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order.” Contempt, however, adheres to the traditional order: it is built like a well-made three-act tragedy. The first part takes place on the deserted back lots of Rome’s Cinecittà studios and at the producer’s house. The second part—the heart of the film—is an extraordinary, lengthy sequence in the couple’s apartment: a tour de force of psychological realism, as the camera tracks the married couple in their casual moves, opening a Coke, sitting on the john, taking a bath in the other’s presence, doing a bit of work, walking away in the middle of a sentence. (This physical casualness is mimicked by a patient, mobile camera that gives the artful impression of operating in real time.) Meanwhile, they circle around their wound: Paul feels that Camille’s love has changed since that morning—grown colder and contemptuous. She is indeed irritated by him, but still loves him. With the devastating force of an Ibsen play, they keep arguing, retreating, making up, picking the scab, until they find themselves in a darker, more intransigently hostile space.

The third part moves to Capri—the dazzling Casa Malaparte, stepped like a Mayan temple by a disciple of Le Corbusier—for a holiday plus some Odyssey location shooting. Capri is an insidious, “no exit” Elysium where luxury, caprice and natural beauty all converge to shatter the marriage and bring about the inevitable tragedy.

Part of Contempt’s special character is that it exists both as a realistic story and a string of iconic metaphors, connecting its historical layers. Palance’s red Alfa Romeo sweeps in like Zeus’ chariot; when he hurls a film can in disgust, he becomes a discus thrower (“At last you have a feeling for Greek culture,” Lang observes dryly); Bardot donning a black wig seems a temporary stand-in for both Penelope and Anna Karina; Piccoli’s character wears a hat in the bathtub to imitate Dean Martin in Some Came Running (though it makes him resemble Godard himself); Piccoli’s bath towel suggests a Roman toga; Lang is a walking emblem of cinema’s golden age and the survival of catastrophe, his anecdotes invoking Dietrich and run-ins with Goebbels; the Casa Malaparte is both temple and prison. Meanwhile, the CinemaScope camera observes all; approaching on a dolly in the opening shot, it tilts down and toward us like a one-eyed Polyphemus. Or is it Lang’s monocle? (“The eye of the gods has been replaced by cinema,” observes Lang.) Primary colors are intentionally used as shorthand for themes. Bardot in her lush yellow robe on the balcony in Capri incarnates all of paradise about to be lost.

What makes Contempt so unique a viewing experience today, even more than in 1963, is the way it stimulates an audience’s intelligence as well as its senses. Complex and dense, it unapologetically accommodates discussions about Homer, Dante, and German Romantic poetry, meditations on the role of the gods in modern life, the creative process, the deployment of CinemaScope ) Lang sneers that it is only good for showing “snakes and funerals,” but the background-hungry, color-saturated beauty of cinematographer Raoul Coutard’s compositions believes this).

It is also a film about language, as English, French, Italian and German speakers fling their words against an interpreter, Francesca (admirably played by Georgia Moll), in a jai alai of idioms which presciently conveys life in the new global economy, while making an acerbic political comment on power relations between the United States and Europe in the Pax America. (More practically, the polyglot sound track was a strategy to prevent the producers from dubbing the film.)

“Godard is the first filmmaker to bristle with the effort of digesting all previous cinema and to make cinema itself his subject,” wrote critic David Thomson. Certainly Contempt is shot through with film buff references, and it gains veracity and authority from Godard’s familiarity with the business of moviemaking. But far from being a

smarty-pants, self-referential piece about films, it moves us because it is essentially the story of a marriage. Godard makes us care about two likable people who love each other but seem determined to throw their chances for happiness away.

Godard is said to have originally wanted Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak for the husband and wife. Some of Novak’s musing, as-you-desire-me quality in Vertigo adheres to Bardot. In her best acting performance, she is utterly convincing as the tentative, demure ex-secretary pulled into a larger world of glamour by her husband. Despite Godard’s claim that he took Bardot as “a package deal,” and that he “did not try to make Bardot into Camille, but Camille into Bardot,” he actually tampered with the B.B. persona in several ways. First he toyed with having her play the entire film in a brunette wig—depriving her of her trademark blondeness—but eventually settled for using the dark wig as a significant prop. More crucial was Godard’s intuition to suppress the sex kitten of And God Created Woman or Mamzelle Striptease, and to draw on a more modest, prudishly French-bourgeois side of Bardot for the character of Camille. In her proper matching blue sweater and headband, she seems a solemn, reticent, provincial type, not entirely at ease with the shock of her beauty.

When she puts on her brunette wig in the apartment scene, she may be trying to get Paul to regard her as more intelligent than he customarily does—to escape the blond bimbo stereotype. (Her foil, Francesca, the dark-haired interpreter, speaks four languages and discusses Hölderlin’s poetry with Lang.) At one point Paul asks Camille, “Why are you looking so pensive?” and she answers, “Believe it or not I’m thinking. Does that surprise you?” The inequalities in their marriage are painfully exposed: he sees himself as the brain and breadwinner, and her as a sexy trophy. Whatever her new-found contemptuous feelings may be, his own condescension seems to have always been close to the surface. “You’re a complete idiot,” he says when they are alone in Prokosch’s house, and later tellingly blurts out, “Why did I marry a stupid twenty-eight-year-old typist?”

On the face of it, her suspicion that Paul had acted as her “pander” by leaving her with his lecherous employer seems patently unjust. Clearly he had told her to get into Prokosch’s two-seat sports car because he did not want to appear foolishly, uxoriously jealous in the producer’s eyes; and we can only assume he is telling the truth when he says his arrival at Prokosch’s house was delayed by a taxi accident. Still, underneath the unfairness of her (implicit) accusation is a legitimate complaint: he would not have acted so cavalierly if he were not also a little bored with her, and willing to take her for granted. Certainly he is not particularly interested in what she has to say about the minutiae of domesticity: the drapes, lunch with her mother. All this he takes in as a tax paid for marrying a beautiful but undereducated younger woman. Her claims to possessing a mind (when she reads aloud from the Fritz Lang interview book in the tub) only irritate him, and he becomes significantly most enraged when she has the audacity to criticize him for filching other men’s ideas (after he proposes going to a movie for screenwriting inspiration).

Camille also says she liked him better when he was writing detective fiction and they were poor, before he fell in with that “film crowd.” His script work does put him in a more self-abasing position, since screenwriting is nothing if not a school for humiliation. We see this in the way Paul, having watched Prokosch carry on like an ass in the projection room, nevertheless pockets the producer’s personal check, after a moment’s hesitation. (It is precisely at this moment in a Hollywood film that the hero would say: Take your check and shove it!) Paul compounds the problem by seeming to blame her for turning hack, saying he is only taking on the job so that they can finish paying for the apartment. It is important to remember that we are not watching the story of an idealistic writer selling out his literary aspirations, since “detective fiction” is not so elevated a genre to begin with, and since Paul’s last screenplay was some junky-sounding movie called Toto Contra Hercules (a dig at Joseph E. Levine), so that, if anything, the chance to adapt Homer for Fritz Lang is a step up.

More important than issues of work compromise is that Camille has come to despise her husband’s presumption that he can analyze her mind. Not only is this unromantic, suggesting she holds no further mystery, but insultingly, reductive. She is outraged at his speculation that she’s making peace for reasons of self-interest—to keep the apartment. As the camera tracks from one to the other, pausing at a lamp in between, Paul guesses aloud that she is angry at him because she’s seen him patting Francesca’s bottom. Here the lamp is important, not only as an inspired bit of cinematic stylization, but as a means of hiding each from the other, if not from the audience. Camille shakes her head in an astonished no at Paul’s misinterpretation, then catches herself. She scornfully accepts his demeaning reading of her as jealous, saying, “Okay, let’s admit that it’s that. Good, now we’re finished, we don’t have to talk about it anymore.”

After he speculates that she no longer loves him because of his dealings with Prokosch, she tells him: “You’re crazy but…you’re intelligent.” “Then it’s true?” he presses, like a prosecutor. “I didn’t say that…I said you were intelligent,” she repeats, as if to link his “craziness” with his intellectual pride, as the thing responsible for his distorted perceptions.

More than anything, the middle section traces the building of a mood. When Paul demands irritably, “ What’s wrong with you? What’s been bothering you all afternoon?” he seems both to want to confront the problem (admirably), and to bully her out of her sullenness (reprehensibly). At first she evades with a characteristically feminine defense: “I’ve got a right to change my mind.” We see what he doesn’t—the experimental, tentative quality of her hostility: she is “trying on” anger and contempt, not knowing exactly where it will go. Her grudge has a tinge of playacting, as though she fully expects to spring back to affection at any moment. She even makes various conciliating moves, assuring him she loves him, but , because of his insecurities, he refuses this comfort. Paul is a man worrying a canker sore. Whenever Camille begins to forgive, to be tender again, he won’t accept it: he keeps asking her why she no longer loves him, until the hypothesis becomes a reality. Paul is more interested in having his worst nightmares confirmed than in rehabilitating the damage.

Perhaps we can understand this Godardian dynamic better by referring to a little-known but key short of his, “Le nouveau monde,” which he shot in 1962 as part of the compilation film ROGOPAG. The protagonist goes to sleep and wakes up to find everything looking the same but subtly different. Pedestrians pop pills nervously, his girlfriend tells him she no longer loves him—just like that. “The New World” has a sci-fi component: while our hero slept, an atomic device was exploded above Paris, which may account for his girlfriend’s spooky, affectless indifference. But the short is also a dry run for Contempt: one day you wake up and love has magically disappeared.

All through the sixties, Godard was fascinated with the beautiful woman who betrays (Jean Seberg in Breathless), withdraws her love (Chantal Goya in Masculin–Féminin), runs away (Anna Karina in Pierrot le Fou) or is faithless (Bardot in Contempt). What makes Contempt an advance over this somewhat misogynistic obsession with the femme fatale is that here, Godard seems perfectly aware how much at fault his male character is for the loss of the woman’s love.

The film’s psychology shows a rich understanding of the mutual complicities inherent in contempt, along with the fact that trying to alter another person’s contemptuous opinion of yourself is like fighting in quicksand: the more you struggle, the farther in you sink. As William Ian Miller wrote in his book The Anatomy of Disgust: “Another’s contempt for or disgust with us will generate shame and humiliation in us if we concur with the judgment of our compatibility, that is, if we feel the contempt is justified, and will guarantee indignation and even vengeful fury if we feel it is unjustified.” Paul responds both ways to his wife’s harsh judgment: 1) he agrees with her, perhaps out of the intellectual’s constant stock of self-hatred, 2) he considers her totally unjust, which leads him to lash out with fury. He even slaps her—further damaging her shaky esteem for him. In any film today, a man slapping a woman would end the scene (spousal abuse, case closed); but in Contempt we have to keep watching the sequence for twenty-five more minutes, as the ramifications of and adjustments to that slap are digested.

In assessing the film, much depends on whether one regards the director’s sympathies as balanced between the couple, or as one-sidedly male. Some women friends of mine, feminists, report that they can only see the male point of view in Contempt: they regard Bardot’s Camille as scarcely a character, only a projection of male desire and mistrust. I see Godard’s viewpoint as more balanced. True, Piccoli’s edgy performance draws a lot of sympathy to Paul; even when he is being an ass, he seems interesting. But Camille also displays striking insights; her efforts to patch things up endear her to us; and her hurt is palpable.

Pascal Aubier told me point-blank: Godard was on Camille’s side.” In that sense, Contempt can be seen as a form of self-criticism: a male artist analyzing the vanities and self-deceptions of the male ego. (And perhaps, too, an apology: what cinematographer Coutard meant when he called the film Godard’s “love letter to his wife,” Anna Karina.)

Still, it can’t be denied that in the end Camille does betray Paul with the vilely virile Jerry Prokosch. It has been Prokosch’s thesis all along that Homer’s Penelope was faithless. Lang, and Godard by extension, reject this theory as anachronistic sensationalism. Godard, you might say, builds the strongest possible case for Camille through the first two acts, but in Act III this Penelope proves faithless.

Bardot’s Camille is a conventionally subservient woman, brought up to defer to her man. “My husband makes the decisions,” she answers Prokosch when he invites her over for a drink. Later she tells Paul, “If you’re happy, I’m happy.” It is her tragedy that, in experiencing a glimpse of independent selfhood—brought about through the mechanism of contempt, which allows her to distance herself from her husband’s domination—she assumes she has no choice but to flee into the arms of another, more powerful man.

Contempt is an ironic retelling of Homer’s Odyssey. At one point Camille wryly summarizes the Greek epic as “the story of that guy who’s always traveling.” But Paul’s restlessness is internal, making him ill at ease everywhere. In modern life, implies Godard, there is no homecoming, we remain chronically homeless, in barely furnished apartments where the red drapes never arrive. Paul’s Odysseus and Camille’s Penelope keep advancing toward and retreating from each other: never arriving at port.

But the film also resembles another Greek tale, OedipusRex. Paul is infantilely enraged at the threatened removal of the nurturing breast, and jealous of a more powerful male figure who must be battled for the woman’s love. The way he keeps pressing to uncover a truth he would be better off leaving alone is Oedipal, too. His insistent demand to know why Camille has stopped loving him (even after she denies this is the case) helps solidify a tentative role-playing on her part into an objective reality (“You’re right, I no longer love you”). Anxious for reassurance, he will nevertheless only accept negative testimony which corroborates his fears, because only the nightmare has the brutal air of truth, and only touching bottom feels real.

Even in Capri, when the game is up, Paul demands one last time: “Why do you have contempt for me?” She answers: “That I’ll never tell you, even if I were dying.” To this he responds, with his old intellectual vanity, that he knows already. By this point, the reason is truly unimportant. She will never tell him, not because it is such a secret, but because she was already moved beyond dissection of emotions to action: she is leaving him.

Godard spoke uncharitably about Alberto Moravia’s The Ghost at Noon, the novel he adapted for Contempt, calling it “a nice, vulgar read for a train journey.” In fact, he took a good deal of the psychology, characters and plot lines from Moravia—a decent storyteller, now neglected, who was once regarded as a major European writer. Perhaps Godard’s ungenerosity toward Moravia reflects an embarrassment at this debt, or a knee-jerk need to apologize to his avant-garde fans.

The exigencies of making a movie with a comparatively large budget and stars, based on a well-known writer’s novel, limited the experimental-collage side of Godard and forced him to focus on getting across a linear narrative. In the process he was “freed” or “obliged” (depending on one’s point of view) to draw more psychologically shaded, complex characters, whose emotional lives rested on overt causalities and motivations, more so than he had ever demonstrated before or since. Godard himself admitted that he considered Paul the first fully developed character he had gotten on film. Godardians regard Contempt as an anomaly, the master’s most “orthodox” movie. The paradox is that it may also be his finest. Pierrot le Fou has more epic expansiveness, Breathless and Masculin–Féminin more cinematic invention, but in Contempt Godard was able to strike his deepest human chords.

If the film records the process of disenchantment, it is also a seductive bouquet of enthrallments: Bardot’s beauty, primary colors, luxury objects, nature. Contempt marked the first time that Godard went beyond the jolie–laide poetry of cities and revealed his romantic, unironic love of landscapes. The cypresses on Prokosch’s estate exquisitely frame Bardot and Piccoli. Capri sits in the Mediterranean like a jewel in a turquoise setting. The last word in the film is Lang’s assistant director (played by Godard himself) calling out “Silence!” to the crew, after which the camera pans to a tranquilly static ocean. The serene classicism of sea and sky refutes the thrashings of men.

-Phillip Lopate

Contempt is one of my favorite Godard films besides Breathless and Vivre sa Vie and I believe it to be one of his most poetic and riches character studies. It’s ironic on how the characters of Ulysses, Penelope and Poseidon all are parallels to the characters in the story who are Paul, Camille and Prokosch. And ironically those character’s parallel director Jean-Luc Godard, his wife Anna Karina (his original choice of female lead), and Joseph E. Levine, the film’s distributor. In one point the film’s lead actress Brigitte Bardot dons a black wig which gives her a resemblance to Anna Karina and Michel Piccoli is said to have bear some resemblance to Brigitte Bardot’s ex-husband, the filmmaker Roger Vadim.

Godard was really annoyed by the paparazzi because of the fame of the beautiful actress Brigitte Bardot who followed them to Capri while he was filming the last third of the film. Godard was not used to large-scale productions so he was not used to all the press which greatly aggravated him. Godard was also not getting along with his wife and usual star of his films Anna Karina and he was very lonely on the shoot. He antagonized Jack Palance and never considered his ideas to his character and only gave him physical instructions. Palance was miserable on the set and even called his agent in America to try to get him off the film. The only one Godard got along very well with was Fritz Lang because he idolized him. Lang was very sick at the time and unfortunately had to cut short his participation with the film. Godard famously said, “a movie should have a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order.”

The film is actually made into three huge parts: The first is in Rome’s Cincecitta studios and at Prokosch’s house. The middle section is in Paul and Camille’s apartment and the third part moves to Capri. There are several metaphors to the story of The Odyssey, like Prokosch speeding in with his red Alfa Romeo like he’s speeding in Zeus’ chariot. Paul’s towel in the bathroom looks like a Roman toga and Fritz Lang is a symbol of the golden age of cinema and a survivor of the horrors of war. “The eye of the gods has been replaced by cinema,” Lang says as the beginning of the film you see a dolly shot that points right at us, the audience which greatly look like a one-eyed Polyphemus.

There are several lush bright colors used in the film, one for instance is Camille wearing a lush yellow robe standing on a balcony in Capri knowing the paradise of her marriage is lost. The story of The Odyssey is about a man who on his long journey home after the fall of Troy, finds out his suitors slept with his wife and has them all executed. That story mirrors what is happening to Paul and Camille. Prokosch is flirting trying to get with Paul’s wife and later in the film when Paul and Camille head to Capri he brings a revolver. Of course it’s never used but Godard purposely adds that in the story to give the film more tension and add some suspense. I personally believe he brought it the sub-plot of the gun as a slight homage to the predictable American thriller, and also as a tease by purposely not using it.

Camille believes her husband is allowing the predatory Prokosch to flirt with her and even at moments purposely leaves Prokosch alone with her even though it is obvious she isn’t comfortable. In some ways this can look like Paul is sort of pimping off his wife as a prostitute for the sake of his job. Because of this, she loses the love she once felt for him, and for selling out his theatre writing talents in now writing for a greedy film company. It seems Paul treats Camille more as a trophy than his actual wife, as a lot of men seem to do when they have money. Camille was once an ex secretary typist and now is pulled into the large world of hollywood and glamour and is struggling to get used to it. Camille admits that she liked Paul better when they were poor and where he was just writing detective novels because he didn’t fall into that snobby wealthy Hollywood crowd, and now is being seduced by money and fame.

Paul seems to insult Camille all the time and treat her like she’s unintelligent. There’s even one point where Paul admits that he prefers her more as a blonde and even states, “You’re a complete idiot, why did I marry a twenty-eight year old typist.” There’s a scene in the apartment where she puts on a black wig. A lot of people claim it was an attempt for Godard to have her look like his wife Anna Karina but I also believe it’s an attempt on the character to look more intelligent to her husband and not the typical ‘blonde bimbo.’ She even says in the film when Paul asks why she is being quite, “Believe it or not I’m thinking.”

I do believe Camille is being rather hard on Paul as well because he would have appeared rather rude or jealous if he didn’t OK Prokosch when Prokosch asked him if his wife could ride with him. I also think he’s telling the truth when he said he was late getting to Prokosch’s house because of a car accident (why would he lie and where would he go?) which let Prokosch have more time to be alone with his wife. However, I do believe he is clearly bored with her because of his flirting with Francesca and patting her on the behind, and he never seems to listen to his wife or care when she’s talking about her mother or simple domestic things about the new apartment that they bough. And when she does try to talk smart or intelligently it seems to anger, like when she’s reading a book on Fritz Lang and especially when she starts to criticize his own writing.

In the apartment scene when he’s questioning Camille he asks her questions trying to sound concerned like, “Whats wrong with you?” or “What’s been bothering you?” when he knows what’s bothering her but he’s to stubborn to come out and admit it. (He also thinks she’s too stupid to not see that he is obviously faking on being clueless and dumb about the situation.) It even sounds like he’s bullying her into coming out with an answer on her irritable behavior. In some ways I think he truly wants her to not love him because he keeps pressing her throughout the film about whether she does or doesn’t and when she does try to forgive he pulls away and doesn’t accept it. Only until his hypothesis becomes real it seems he truly cares. Paul is more interested in having his fears confirmed then trying to prevent them from happening in the first place.

I also find it interesting that he always tries to figure out what his wife is thinking and why she does things, while she is always telling him why he will do things and what he will not do. There’s some interesting asymmetry there, that his wife knows him better than he knows her and even himself. In some ways he does sell his soul to the Hollywood producer Prokosch after taking a check from him in the screening room right after he sees Prokosch make a ridiculous fit of angrily throwing film cans around the room. Lang isn’t very amused and not at all surprised at this behavior, probably because he’s seen the worst of the worst, when it comes to shady and corrupt dealings in Hollywood, especially during the pre-war days in Germany.

Godard is clearly stating his ‘contempt’ and distain for Hollywood studios and producers with this film, probably because Godard had his fair share of problems not only getting this film made, but all his other films in the past. It’s because of seedy business men like Prokosch who only care about making money within the film industry and who have tried holding back Godard and other artists on their attended visions. He purposely writes Lang’s character (who Godard believes is the embodied of a true film artist) as a person who does not get along well with Prokosch and even has him say in the film, “Producers are something I can easily do without.”

Language is another important theme in Contempt as you see many English, French, Italian and German speakers speak through a translator; Francesca. It shows how languages and culture merge with the political comment on power relations in the film industry with The United States and Europe; and shows the relationship distance with character’s that don’t speak the same language. I find it funny that several of the phrases, insults and sarcastic comments mostly by Lang thrown at Prokosch aren’t translated very well and Prokosch never seems to catch them. Prokosch isn’t a very bright person and he’s the type of rich businessman that gets rich on buying ideas from creative people.

Originally Italian film producer Carlo Ponti approached Jean Luc Godard to discuss a possible collaboration; Godard suggested an adaptation of Moravia’s novel Il disprezzo (originally translated into English with the title A Ghost at Noon) in which he saw Kim Novak and Frank Sinatra as the leads; and they refused. Ponti suggested Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, whom Godard refused. Finally, Bardot was chosen, because of the producer’s insistence that the profits might be increased by displaying her famously sensual body. Producers Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine were upset that the rough cut was so tame so Godard abliged to add in the prologue of the husband and wife in bed and shot Bardot nude with color filters. The film’s opening scene, filmed by Godard is a purposeful typical mockery of the cinema business. Beyond that compromise Godard refused to budge saying, “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?” In the film, Godard cast himself as Lang’s assistant director, and characteristically has Lang expound many of Godard’s New Wave theories and opinions. The soundtrack to Contempt is masterful and is one of the main true powers of the film. It’s plays all throughout the story and it’s one of those rare scores that sticks with you long after watching the movie. It has a tragic and sad underlining to the music that really represents the tragic relationship that is slowly unfolding. The music was done by George Delerue and it really shows how music can set the feel and the tone of the film, and is one of my favorite film scores of all time. Contempt was filmed in and occurs entirely in Italy, with location shooting at the Cinecittà studios in Rome and the Casa Malaparte on Capri island. In the infamous apartment sequence with the two main characters wandering through their apartment alternately arguing and reconciling, Godard filmed the scene as an extended series of tracking shots, in natural light and in near real-time. The extraordinary cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, shot some of the seminal films of the Nouvelle Vague, including Godard’s masterpiece Breathless. One of the most notable reviews for Contempt is Sight & Sound critic Colin MacCabe calling it “the greatest work of art produced in postwar Europe.” Contempt has influenced a generation of filmmakers including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese who made his own homage by using the Godard films beautiful musical score in the movie Casino. Scorsese called Contempt, “brilliant, romantic and genuinely tragic, and also one of the greatest films made about the actual process of filmmaking.” Contempt‘s ending is tragic but expected, because the story has to end tragically to parallel the tragic story of The Odyssey. Art represents life, which does occur when Camille decides to leave Capri with Prokosch. And yet, why does Camille leave with him in the end if she despised him all throughout the film? I think it was more of a payback to Paul and I doubt she left with him to truly be with him. She leaves a letter for Paul that reads: “Dear Paul. I found your revolver and took the bullets out. If you wont leave I will. Since Prokosch has to return to Rome, I’m going with him. Then I’ll probably move in a hotel alone. Take care. Farewell. Camille.” I find it interesting that the fatal car accident that Prokosch and Camille get into is not shown which makes the ending seem much more surreal. You only hear the accident while Godard shows the close-up of her writings of the note that she left for Paul; most importantly the words ‘farewell’ and ‘Camille.’ Even when Godard shows the aftermath of the accident it doesn’t look very realistic, and the blood looks like bright red paint (which looks similar to the surreal like violence in his film Pierrot le fou. I believe what Godard is trying to do with this film is show the audience that this story is as fictional as the story of The Odyssey. The last shot ends on a beautiful note with Fritz Lang finishing up his filming of The Odyssey as the camera pans past the film crew and into the ocean with just hearing Lang yell “silence!” off-screen. I would place Contempt up along-side other classics like Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, Frances Truffaut’s Day of Night, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, and Robert Altman’s The Player as one of the greatest films to portray the business and personal sides of movie making. It’s also a tragic portrait of an artists slow deteriorating integrity and marriage, which sadly symbolizes a paradise…now lost.

Originally Italian film producer Carlo Ponti approached Jean Luc Godard to discuss a possible collaboration; Godard suggested an adaptation of Moravia’s novel Il disprezzo (originally translated into English with the title A Ghost at Noon) in which he saw Kim Novak and Frank Sinatra as the leads; and they refused. Ponti suggested Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, whom Godard refused. Finally, Bardot was chosen, because of the producer’s insistence that the profits might be increased by displaying her famously sensual body. Producers Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine were upset that the rough cut was so tame so Godard abliged to add in the prologue of the husband and wife in bed and shot Bardot nude with color filters. The film’s opening scene, filmed by Godard is a purposeful typical mockery of the cinema business. Beyond that compromise Godard refused to budge saying, “Hadn’t they ever bothered to see a Godard film?” In the film, Godard cast himself as Lang’s assistant director, and characteristically has Lang expound many of Godard’s New Wave theories and opinions. The soundtrack to Contempt is masterful and is one of the main true powers of the film. It’s plays all throughout the story and it’s one of those rare scores that sticks with you long after watching the movie. It has a tragic and sad underlining to the music that really represents the tragic relationship that is slowly unfolding. The music was done by George Delerue and it really shows how music can set the feel and the tone of the film, and is one of my favorite film scores of all time. Contempt was filmed in and occurs entirely in Italy, with location shooting at the Cinecittà studios in Rome and the Casa Malaparte on Capri island. In the infamous apartment sequence with the two main characters wandering through their apartment alternately arguing and reconciling, Godard filmed the scene as an extended series of tracking shots, in natural light and in near real-time. The extraordinary cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, shot some of the seminal films of the Nouvelle Vague, including Godard’s masterpiece Breathless. One of the most notable reviews for Contempt is Sight & Sound critic Colin MacCabe calling it “the greatest work of art produced in postwar Europe.” Contempt has influenced a generation of filmmakers including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese who made his own homage by using the Godard films beautiful musical score in the movie Casino. Scorsese called Contempt, “brilliant, romantic and genuinely tragic, and also one of the greatest films made about the actual process of filmmaking.” Contempt‘s ending is tragic but expected, because the story has to end tragically to parallel the tragic story of The Odyssey. Art represents life, which does occur when Camille decides to leave Capri with Prokosch. And yet, why does Camille leave with him in the end if she despised him all throughout the film? I think it was more of a payback to Paul and I doubt she left with him to truly be with him. She leaves a letter for Paul that reads: “Dear Paul. I found your revolver and took the bullets out. If you wont leave I will. Since Prokosch has to return to Rome, I’m going with him. Then I’ll probably move in a hotel alone. Take care. Farewell. Camille.” I find it interesting that the fatal car accident that Prokosch and Camille get into is not shown which makes the ending seem much more surreal. You only hear the accident while Godard shows the close-up of her writings of the note that she left for Paul; most importantly the words ‘farewell’ and ‘Camille.’ Even when Godard shows the aftermath of the accident it doesn’t look very realistic, and the blood looks like bright red paint (which looks similar to the surreal like violence in his film Pierrot le fou. I believe what Godard is trying to do with this film is show the audience that this story is as fictional as the story of The Odyssey. The last shot ends on a beautiful note with Fritz Lang finishing up his filming of The Odyssey as the camera pans past the film crew and into the ocean with just hearing Lang yell “silence!” off-screen. I would place Contempt up along-side other classics like Federico Fellini’s 8 ½, Frances Truffaut’s Day of Night, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, and Robert Altman’s The Player as one of the greatest films to portray the business and personal sides of movie making. It’s also a tragic portrait of an artists slow deteriorating integrity and marriage, which sadly symbolizes a paradise…now lost.