Breathless (1960)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Breathless Jean Luc Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]In its opening shots a girlie tabloid slips down to reveal the face of a man, a cigarette dangling on his lips as his eyes suspiciously survey’s the area under his jaunty cocked hat that is obviously too large for his head. He turns and he rubs those lips with the edge of his thumb; and he is ready for action. At a signal from a female accomplice across the street he hot-wires a big Oldsmobile just parked by an American tourist. The girl begs to be taken along, but the man coldly abandons her, and quickly drives off, as the audience feels an exhaling rush of outlaw freedom letting loose in this opening sequence, a Hollywood crime genre set in overdrive. The film irregularly jump-cuts within continuous movement or dialogue, trying no attempts at all to make them match, as bursts of pop music and sound effects occur in the background, and you hear the man spout off spontaneous dialogue which are directed towards the camera, towards us. “If you don’t like the sea… if you don’t like the mountains…if you don’t like the city… then get stuffed!” Ladies and gentlemen, this is the film that started it all. All the modern movies started here with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. There hasn’t been a film début so influential, so groundbreaking and so changed the fundamental rules of film since Orson Welles Citizen Kane. Every music video that you have seen on MTV, every popcorn action flick that you watch in the theatre and every movie with throwaway film references wouldn’t have begun if it wasn’t for Breathless. It was also the radical technique of jump cuts which became a huge breakthrough in the way films were conceived and constructed, which was a very startling innovation for audiences to witness at the time Breathless was released, with critic Andrew Sarris stating, “the meaninglessness of the time interval between moral decisions.” [fsbProduct product_id=’744′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Breathless became the quintessential film of the French New Wave which was a movement that rejected the traditional French cinema and embraced a rougher, more freewheeling style of film-making, often choosing to shoot on location, using natural lighting and hand-held cameras which added a personal and experimental feel for the films. Many of the New Wavers were critics for the anti-establishment magazine Cahiers du Cinema which included Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette and some were even working on Breathless, including not only Godard’s direction but an original story written by Francois Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol as the production designer. (Jean-Pierre Melville, plays the classic novelist interviewed by Patricia at Orly, in which he explains his own theories on life, sex and women). And yet what makes Breathless extremely pivotal was the cool detachment of narcissistic characters who were selfish, obsessed with themselves and oblivious to society and of the outside world. Michel, the main character in Breathless is a rebellious and arrogant youth who believes he is invincible to the brutal realities of the law and pretends to be as tough as the movie stars he sees in the movies. These anti-heroes in the cinema was a direct response to the anti-establishment of authority figures and of the rebellious youth in the late 1960’s, which would start a trend that would be created and expanded upon again in again in America with new and fresh upcoming stars like Robert Deniro, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman Dennis Hopper, and Robert Duvall during Hollywood’s 1967-1974 Golden-Age.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Breathless Jean Luc Godard” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]In its opening shots a girlie tabloid slips down to reveal the face of a man, a cigarette dangling on his lips as his eyes suspiciously survey’s the area under his jaunty cocked hat that is obviously too large for his head. He turns and he rubs those lips with the edge of his thumb; and he is ready for action. At a signal from a female accomplice across the street he hot-wires a big Oldsmobile just parked by an American tourist. The girl begs to be taken along, but the man coldly abandons her, and quickly drives off, as the audience feels an exhaling rush of outlaw freedom letting loose in this opening sequence, a Hollywood crime genre set in overdrive. The film irregularly jump-cuts within continuous movement or dialogue, trying no attempts at all to make them match, as bursts of pop music and sound effects occur in the background, and you hear the man spout off spontaneous dialogue which are directed towards the camera, towards us. “If you don’t like the sea… if you don’t like the mountains…if you don’t like the city… then get stuffed!” Ladies and gentlemen, this is the film that started it all. All the modern movies started here with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. There hasn’t been a film début so influential, so groundbreaking and so changed the fundamental rules of film since Orson Welles Citizen Kane. Every music video that you have seen on MTV, every popcorn action flick that you watch in the theatre and every movie with throwaway film references wouldn’t have begun if it wasn’t for Breathless. It was also the radical technique of jump cuts which became a huge breakthrough in the way films were conceived and constructed, which was a very startling innovation for audiences to witness at the time Breathless was released, with critic Andrew Sarris stating, “the meaninglessness of the time interval between moral decisions.” [fsbProduct product_id=’744′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Breathless became the quintessential film of the French New Wave which was a movement that rejected the traditional French cinema and embraced a rougher, more freewheeling style of film-making, often choosing to shoot on location, using natural lighting and hand-held cameras which added a personal and experimental feel for the films. Many of the New Wavers were critics for the anti-establishment magazine Cahiers du Cinema which included Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette and some were even working on Breathless, including not only Godard’s direction but an original story written by Francois Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol as the production designer. (Jean-Pierre Melville, plays the classic novelist interviewed by Patricia at Orly, in which he explains his own theories on life, sex and women). And yet what makes Breathless extremely pivotal was the cool detachment of narcissistic characters who were selfish, obsessed with themselves and oblivious to society and of the outside world. Michel, the main character in Breathless is a rebellious and arrogant youth who believes he is invincible to the brutal realities of the law and pretends to be as tough as the movie stars he sees in the movies. These anti-heroes in the cinema was a direct response to the anti-establishment of authority figures and of the rebellious youth in the late 1960’s, which would start a trend that would be created and expanded upon again in again in America with new and fresh upcoming stars like Robert Deniro, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman Dennis Hopper, and Robert Duvall during Hollywood’s 1967-1974 Golden-Age.

PLOT/NOTES

The film opens as a young man named Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is staring at a car parked near a sidewalk café at the bottom of the Cannebiere, but at the same time is pretending to read a girlie tabloid. “After all, I’m an asshole,” Michel says. “After all, yes, I’ve got to. I’ve got to!” A girl signals Michel across the street that the owners went into the café without locking the doors. This man is wearing an overcoat and a hat that obviously is to large for his head. He has a cigarette in his mouth (where most characters in this film always either are smoking or lighting up another one. )

Michel hot wires the car and calmly gets in as if he has done this several times before. The girl who signaled him walks across the street towards him and asks to take her with him but he refuses and quickly takes off. While he is on the highway driving this stolen car he starts to sing as he passes cars that he feels are driving to slow on the road. “I collect the dough. I ask Patricia if its yes or no, and then…” He slows down along side two young girls who are hitchhiking. He checks them out but then quickly drives off again saying, “Oh, hell, they’re both dogs.” He says a lot of thing out loud which include his current projects and motivations. Some of the remarks he makes says to the audience, and at one point even acknowledges the camera by looking into it and saying, “If you don’t like the sea… if you don’t like the mountains…if you don’t like the city… then get stuffed!”

After stealing the car, his goal is to head to Paris to receive some money that he believes is owed to him because of some past shady deals. We never really find out what kind of work he does, nor as an audience we don’t really care because were more taken into this exciting and reckless lifestyle and we have no idea where it will all lead to next. Michel wants to head to Paris to also meet up with an American girl who he ‘believes’ he loves, so they can go abroad together.

Of course his plans get more complicated when he gets annoyed because of being caught behind a slow moving vehicle and decides to speed to pass around them. Suddenly a motorcycle cop catches him and signals him to stop and pull over, but Michel being in a stolen car tries to outrun him and hides in a cul-de-sac. His car dies pulling over and after finding a handgun in the glove compartment of the vehicle, the motorcycle cop eventually finds him and Lucien impulsively shoots him with that gun. Everything happens all at once before Michel even realizes it. He is furious with himself because the last thing he needs is something like this on his record.

Michel of course flees and seems to hitchhike a cab which drops him off towards the Seine early the next morning. He is now wearing only his shirt stupidly leaving his jacket in the stolen car. Michel goes into a telephone booth, then changes his mind and hangs up without making a call. He looks at a morning France-soir but there is no news yet of the murder. During this morning he goes to a residential hotel on the Seine asking if Miss Patrica Franchini is there. When he is told she is out he steals her door key when the door man’s not looking. He enters Patricia’s room and notices her bed has not been slept in. After searching around the room he finds some change in a drawer but they are American coins, and leaves. “Girls never have cash,” he says.

Later on that day we follow him enter the Royle Saint-Germaine and ask for a price of eggs, counting his change and realizes he only has enough for one. Michel goes and buys a afternoon France-soirto see if the murder has yet been reported but he still sees nothing, and so he uses the paper to clean his shoes. Michel crosses the street boulevard Saint-Germain and enters a courtyard of apartments. We then see him enter a apartment complex and a girl in pajama bottoms lets him in right away noticing him without a jacket. We don’t learn much about Michel and the girl except we discover she is an assistant as a script girl. Michel asks if he can borrow money, but she only offers him 500 calling him rotten. He turns down her 500 and she turns down his offer for breakfast. While she isn’t looking Michel seems to steal all her money from her bag and soon takes off.

Michel enters a travel agency and asks the front desk for a man named Antonio but the employee tells him he will arrive back around 11:00. Michel asks for the directions of the New York Herald Tribune. When entering the New York Herald Tribune Michel he asks for Miss Patricia Franchini, and he is told she should be on the Champs-Elysees selling papers. Michel leaves and walks down the Champs-Elysees looking for Miss Patricia Franchini, and a girl points her out on the other side of the sidewalk.

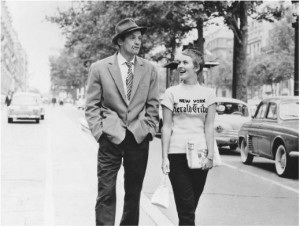

He then approaches Patricia on the Champs-Esyees street selling newspapers shouting “New York Herald Tribune!” He shouts out to Patricia to get her attention saying, “Come with me to Rome? It’s crazy, but I love you.” Patricia is surprised to see Michel because she thought he hated Paris. Michel tells her he has enemies in Paris and asks her again to come to Rome with him. Patricia who is an American working for the New York Tribune is waiting to enroll at the Sorbonneand. Patricia thought Michel was in Monto Corlo. When he tells her he arrived in Paris for business we learn from their conversation that they lived together some weeks ago in Cote d Azur where Patricia was spending her holiday and she left without saying goodbye. He then again asks if Patricia would leave with him to Italy. She doesn’t yes or no to Michel and says she’ll have to see. She must register at the Sorbonne and will perhaps be writing some articles for the New York Herald. They arrange to meet later that evening at a café on the Boulevards where she will be and Patricia kisses Michel goodbye after he purchases a paper (not from her). There is a funny moment when leaving where a student selling newspapers confronts Michel and asks him he has anything against youth. Michel snubs her and replies, “Sure do. I prefer old people.”

We follow Michel again as he heads towards the same travel agency as before. On a small street in front of the Biarritz he witnesses a fatal motor accident, where it looks a man on a motor scooter was hit by a car (which has Michel recall the cop he killed earlier). Inside the Agency he finds Antonio who this time is there. Antonio hands him an envelope and says everything will be settled with their dealer but Michel is angry because he expected cash not a check; worse yet, it is for deposit only. Antonio insists he knows nothing about the deal Michel has made, and is only making a transfer, advising Michel should see Berruti, who he saw in Montparnasse last night. Michel uses a phone to telephone Berruti, who is not in. Michel informs Antonio that he plans on leaving to Rome with an American.

Right after Michel leaves two detectives enter and arrive at the front desk. They ask if anyone has seen Michel Poiccard and question Antonio knowing Antonio has ratted before and will eventually rat again. Antonio doesn’t say anything and when the front desk woman says that Michel just came in five minutes before the detectives quickly run out to try to find him but Michel already got away getting using the metro. When the detectives drop down into the metro, Michel reappears coming back up and entering the cinema next door which is advertising the movie The Harder They Fall starring Humphrey Bogart. Michel stops and lingers in front of the poster of Bogart for several moments, with a cigarette dangling on his lips as he rubs those lips with the edge of his thumb.”Bogey…” he says.

That evening Michel and Patricia rejoin outside on the Boulevards to go out to eat as they planned. Before leaving to a restaurant Michel has to leave for a second to make a phone-call, (he really is broke and realizes he has to steal some cash). Patricia says when he leaves, “The French always say one second when they mean five minutes.” To get some cash Michel decides to knock unconscious a bathroom attendee and drag his body into the stall, robbing him. Michel hurries to meet up with Patricia telling her of a story he read of a bus conductor saying, “He stole five million to seduce a girl, posing as a rich impresario. He took her to the Riviera. They blew the wad in three days. The guy didn’t cop out, he told her, ‘It’s stolen money. I’m a hood, but I like you.’ What is great is that she stuck by him.”

They are going to eat at a restaurant but suddenly Patricia remembers that she has to see one of editors at the New York Herald who promised to have some articles for her. Tomorrow there is a novelist to interview and the woman who usually does the interviews is not there so there might be a spot open for her to replace the woman at the press conference to interview him. Michel asks if she sleeps with her editor but Patricia tells him its none of his business. She asks Michel to escort her to the appointment, and Michel agrees.

They get into Michel’s stolen car and Michel starts to ramble saying, “Woe is me! I love a girl with a pretty neck, pretty breasts, a pretty voice, pretty wrists, a pretty forehead, and pretty knees…” and while Michel goes on with his spontaneous ramblings the camera irregularly jump-cuts within continuous movement and dialogue that clearly does not match-up. Michel forbids Patricia to see her editor but she just ignores him. Michel leaves Patricia off in front of the Pergola café at the top of the Champs-Elyees and angrily says, “I never want to see you again. Get lost! You make me want to puke.”

The camera stays with Patricia as she goes up the escalator and meets up with her editor on the second floor. Patricia says to her editor, “If I could dig a hole to hide in, I would.” The editor says, “Do like elephants do. When they’re sad…they vanish.” She then says, “I don’t know if I’m unhappy because I’m not free, or I’m not free because I’m unhappy.” After chatting a little (changing from French to English) and getting the instructions for the upcoming press conference tomorrow Patricia leaves and with the editor as Michel follows. The two walk down the Champs-Elysses, where the editor is parked. Michel buys another paper while watching Patricia and the editor. Michel unhappily catches the two of them as they romantically kiss, and Patricia gets in the editor’s car and spends the night at his place.

The next morning Patricia returns home on foot, and admires herself in a store window before realizing her apartment key is not at the front desk. “What the heck!” she says when catching Michel in her apartment sleeping in her bed. He explains that all the hotels are full of tourists. Patricia is somewhat annoyed and Michel tells her to stop making a face. When she asks him what ‘making a face’ means in French Michel shows Patricia his three forms of facial expressions, the happy face, sad face, and angry face. “It suits me just fine,” she says. Michel asks Patricia what she is thinking and she says, “I’d like to think about something but I can’t seem to.”

Michel continues to ask if she will leave to Rome with him, and follows that question with many others like “if she is sleeping with her editor,” or “if she will sleep with him.” Patricia says she didn’t sleep with her editor, (I highly doubt it) as the two start to chat about nonsensical things. This bedroom sequence is a long character study full of dialog and simple banter between the two of them as they chat about everyday unimportant topics. Michel keeps pressing Patricia on about sex but she isn’t sure if she wants to sleep with him yet, even though it’s obvious they have done it before. Michel says “Women will never do in eight seconds what they would gladly agree do in eight days. It gets me down.” He starts to tease her and lightly takes her neck, “All right, I’ll count to 8, and if you haven’t smiled, I’ll strangle you.” When given the opportunity Michel grabs Patricia’s bottom, in which she slaps him which he so happily enjoys.

Patricia sees Michel’s passport and Michel lies saying it is his brothers, and when she sees that the last name says Kovacs he lies again and says his brother is adopted. While Michel rambles on while sitting below a Picasso poster of a man holding a mask, Patricia is roaming around the room trying to figure out where to place a poster she has in her apartment. Michel asks why she earlier slapped him for grabbing her legs. She tells him it wasn’t her legs and Michel tells her its all the same thing as he lightly caresses her. Patricia says, “The French always say things are the same when they’re not at all.” Michel says some classic dialogue like his opinions on catching a liar (which he obviously is, and a bad one at that), “It’s like with poker. It’s better to tell the truth. The others think you’re bluffing, and that’s how you win.” and “I always get interested in girls who aren’t right for me.”

There’s a neat little shot where Patricia wraps the poster up and peers through it like a telescope looking at Michel. He tries to pose like Bogart holding his cigarette up to his mouth. Patricia poses in front of a Renoir poster, and asks who is prettier and at one point Patricia even says she is pregnant with Michel’s child, but has to see the doctor again to be sure. Michel doesn’t seem to really take what Patricia is saying too seriously (or he just doesn’t care) as he makes a phone-call and tries again to get in touch with Berruti. Not getting any luck he says to Patricia, “Some idea, having a kid!” Patricia says she’s not too sure and wanted to see what Michel would say. One minute Michel says he loves Patricia and the next minute he insults her by saying, “You Americans are so dumb. You adore Lafayette and Maurice Chevalier. And they’re the dumbest French!”

Patricia tries to talk about things like music and literature which Michel seems to know nothing about and is more focused on just getting into Patricia’s pants, and gets slapped once again. Michel playfully hides himself under the blanket and at one moment Patricia sits beside Michel and puts on his large hat. Michel keeps pushing sex on Patricia, as the two continue to discuss various different topics like love, music, death, age, fears, love, poetry, jobs, sex and how many partners they each had. Patricia asks him if he knows William Faulkner and he says, “No, who’s he? Someone you slept with?” She then quotes to him Faulkner saying “Between grief and nothing, I will take grief.” Michel thinks for a moment (If you consider he actually thinks) and then says “Grief’s stupid. I’d choose nothing. Its not better but griefs a compromise. I want all or nothing.” Patricia describes when she closes her eyes they are never entirely black. Throughout this whole bedroom sequence, the two keep lighting up cigarettes and discarding them out her apartment window as they chat about a little of everything with a few arguments in between and a make up which eventually leads to sex.

After sex and a little nap Patricia gets ready for her press conference with the novelist for the paper which is located at Orly. Patricia waits for Michel as he lies and says he is going to pick up his car at the garage, in which he has precisely the right amount of time to find a care and steal it. He locates one, a Ford Thunder and the driver gets out and enters an apartment building. Michel follows him, getting in the elevator with him and watches him go into a office. Immediately, Michel dashes back down, hot-wires the car, and takes off to pick up Patricia at the sidewalk cafe. While driving Patricia to her interview in Orly Michel buys the evening France-soir and finds his picture is on the front page in which the headline reads: “Police killer still at large.” A pedestrian reading the France-soirto (which is Godard) notices Michel from the photo and immediately seeks a police officer on the street after Michel drives off. During Patricia’s press conference with the famous novelist (played by film director Jean-Pierre Melville) the writer dissects the issues on life, death, woman and sex. There’s some classic comments his character gives to several of his reporter’s questions:

“Which is more moral: an unfaithful woman or a man who walks out?”

“An unfaithful woman.”“Two things matter in life. For men, its women, and for women, money.”

“Are French women romantically different from American women?”

“French women are totally unlike American women. The American woman dominates the man. The French woman doesn’t dominate him.”

“If you see a pretty girl with a rich man, you know she’s nice and he’s a bastard.

“What’s your greatest ambition?”

“To become immortal… and then die.”

While Patricia attends the press conference, Michel tries to sell the Ford Thunder in the suburbs. He has trouble with the used car-dealer when the dealer promises Michel he will pay him later in cash for the vehicle. The dealer recognizes Michel from the wanted photo in the France-soirto. He is quite willing to buy Michel’s stolen car but won’t give him the money for several days. When making a phone call to the New York Herald and asking if Patricia is there (Michel’s making sure the conference is finished) the car-dealer overhears this and removes the distributor cap on the Thunder-bird making the vehicle not able to start. When Michel realizes this he attacks the car-dealer and steals what money he has on him for a quick cab right back in the city to pick Patricia up.

He lies and tells Patricia the Thunder-bird is in the shop after an accident and harasses the cap driver to drive faster. Patricia points to a pedestrian with a short dress and talks about her disgust for Parisian women and how they rely on rich men, wearing tasteless short dresses that the wealthy men buy for them. Michel describes wanting to run behind those women and lift up their short dresses and at one point even shows Patricia his sexist point by having the cab driver pull over and Michel runs out on the street and lifts up a unsuspecting pedestrian’s dress.

Michel waits across the street for Patricia as she walks in the the New York Herald to bring her article to the editorial department. Because of the car-dealer the two detectives arrive to speak to Patricia and show her the photo of Michel in the France-soir. Patricia calmly says to them that she in fact has gone out with Michel five or six times but doesn’t know where to find him. The detectives give her their telephone number and to call if she sees him again. She leaves and is aware that one of the detectives is following her and signals for Michel across the street to follow the detective while the detective follows her.

Patricia runs into a movie theater and escapes using the restroom backdoor losing the detective and reuniting with Michel. The two decide to go watch a western and after the movie they pick up a France-soir and look for a hotel to spend the night. Patricia reads in the France-soir that a public manhunt is out for Michel as it also says that Michel is married. Michel lies again saying, “that was ages ago. She was a wacko. She dumped me,” Patricia stupidly accepts it and says she is fond of Michel. She is excited to be in a stolen vehicle and with a fugitive wanted from the police for killing a police officer. Patricia is curious how the detectives knew she was with him and Michel says that someone must have informed. She believes informers are horrible and Michel says, “No, its normal. Informers, inform, burglars burglar, Murderers murder, lovers love.”

Michel even more desperately looks for Berruti, to have him cash his check. Michel runs into various people in various quarters (a girl at Strasbourg, and a bar owner near the Saint-Germain.) Knowing they have to switch vehicles, Michel shows Patricia the ‘garage scam.’ Which is, they drive the car into a parking garage that only has a single, aged attendant. He leaves it on the third level and takes another. He has Patricia, whom he had told to hide when they drove in, take the wheel of the car. The old man, seeing a pretty woman driving an impressive car, says nothing when they leave.

Finally, Michel gets in touch with Berruti, who has been hanging around Montparnasse with Antonio; Berruti promises to help Michel. Perhaps as soon as tomorrow he will be able to cash his check. In the meantime Michel explains his problems to Berruti, who gives him the address of a model who is never home, saying Patricia and him can spend the night there, (meanwhile Patricia runs into her editor and he informs her that he gave their boss her interview.) Michel and Patricia arrive at the model’s studio which is near the end of a photo-shoot. When everyone leaves Patricia and Michel alone, Patricia puts on a record of The Clarinet Concerto by Mozart. Patricia says, “Want to go to bed? Sleeping’s so sad. We have to separate. You say ‘sleep together,’ but you don’t.”

The next morning Patricia goes to purchase milk and a France-soir. She then for whatever reason betrays Michel and calls the investigator’s phone number that he earlier gave her and gives him their address. When returning to the studio Michel tells Patricia that Antonio’s coming with the money. “We’re going to Italy, kid,” says Michel. Patricia tells Michel that she can’t go and reveals that she called the police and they’re on their way. “I don’t want to be in love with you,” Patricia says roaming around the studio. “That’s why I called the police. I stayed with you to make sure I was in love with you. Or that I wasn’t. And since I’m being mean to you, it proves I’m not in love with you.” While she reveals all this Michel angrily says, “You’re like the girl who sleeps with everyone, except the one who loves her…saying it’s because she sleeps with everyone.” She asks why he doesn’t leave and what Michel’s waiting for. Michel says that he is staying, and that he prefers prison.

Antonio arrives outside with the cash and Michel tells him that the American girl turned him in. Michel says he is fed up and he is staying because he is tired. Antonio gives him his pistol but he doesn’t want it. When the cops arrive Antonio throws Michel the pistol and when Michel picks it up he is shot in the streets. Michel injured, runs for a little bit but eventually collapses in the middle of the street.

Patricia arrives by Michel’s side and Michel shows Patricia his three forms of facial expressions, the happy face, sad face, and angry face; which he did earlier in the apartment. He then says to her, “Makes me want to puke” and dies. Patricia asks the detective what Michel said and the detective translates it for her. “What that mean, ‘puke’?” she asks while she rubs her lips with the edge of her thumb. Ironically the final lines of dialogue in the film confused English-speaking audiences as well. In some translations, it is unclear whether Michel is condemning Patricia, or alternatively condemning the world in general.

FRENCH NEW WAVE

The New Wave was a blanket term coined by critics for a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Although never a formally organized movement, the New Wave filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of the literary period pieces being made in France and written by novelists, their spirit of youthful iconoclasm, the desire to shoot more current social issues on location, and their intention of experimenting with the film form. “New Wave” is an example of European art cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm.

Using light-weight portable equipment, hand-held cameras and requiring little or no set up time, the New Wave way of film-making presented a documentary style. The films exhibited direct sounds on film stock that required less light. Filming techniques included fragmented, freeze-frames, discontinuous editing, and long takes. The combination of objective realism, subjective realism, and authorial commentary created a narrative ambiguity in the sense that questions that arise in a film are not answered in the end.

Alexandre Astruc’s manifesto, “The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera-Stylo”, published in L`Ecran, on 30 March 1948 outlined some of the ideas that were later expanded upon by François Truffaut and the Cahiers du cinéma. It argues that “cinema was in the process of becoming a new mean of expression on the same level as painting and the novel: a form in which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel. This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the ‘camera-stylo.”

Some of the most prominent pioneers among the group, including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, began as critics for the famous film magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Cahiers co-founder and theorist André Bazin was a prominent source of influence for the movement. By means of criticism and editorialization, they laid the groundwork for a set of concepts, revolutionary at the time, which the American film critic Andrew Sarris called the ‘auteur theory.’

Cahiers du cinéma writers critiqued the classic “Tradition of Quality” style of French Cinema. Bazin and Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, were the dual godfather figures of the movement. These men of cinema valued the expression of the director’s personal vision in both the film’s style and script.

The ‘auteur theory’ holds that the director is the “author” of his movies, with a personal signature visible from film to film. They praised movies by Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, and made then-radical cases for the artistic distinction and greatness of Hollywood studio directors such as Orson Welles, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray. The beginning of the New Wave was to some extent an exercise by the Cahiers writers in applying this philosophy to the world by directing movies themselves.

Truffaut, with The 400 Blows (1959) and Godard, with Breathless (1960) had unexpected international successes, both critical and financial, that turned the world’s attention to the activities of the New Wave and enabled the movement to flourish. Part of their technique was to portray characters not readily labeled as protagonists in the classic sense of audience identification.

The auteurs of this era owe their popularity to the support they received with their youthful audience. Most of these directors were born in the 1930s and grew up in Paris, relating to how their viewers might be experiencing life. They were considered the first film generation to have a “film education”, knowledge of and references to film history. With high concentration in fashion, urban professional life, and all-night parties, the life of France’s youth was being exquisitely captured.

The French New Wave was popular roughly between 1958 and 1964, although New Wave work existed as late as 1973. The socio-economic forces at play shortly after World War II strongly influenced the movement. Politically and financially drained, France tended to fall back on the old popular pre-war traditions. One such tradition was straight narrative cinema, specifically classical French film.

The movement has its roots in rebellion against the reliance on past forms (often adapted from traditional novelistic structures), criticizing in particular the way these forms could force the audience to submit to a dictatorial plot-line. They were especially against the French “cinema of quality”, the type of high-minded, literary period films held in esteem at French film festivals, often regarded as ‘untouchable’ by criticism.

New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what was, to them, a much more comfortable and contemporary form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized. French New Wave were also influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema.

The French New Wave featured unprecedented methods of expression, such as long tracking shots (like the famous traffic jam sequence in Godard’s 1967 film Week End). Also, these movies featured existential themes, such as stressing the individual and the acceptance of the absurdity of human existence. Filled with irony and sarcasm, the films also tend to reference other films.

Many of the French New Wave films were produced on tight budgets; often shot in a friend’s apartment or yard, using the director’s friends as the cast and crew. Directors were also forced to improvise with equipment (for example, using a shopping cart for tracking shots). The cost of film was also a major concern; thus, efforts to save film turned into stylistic innovations. For example, in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, after being told the film was too long and he must cut it down to one hour and a half he decided (on the suggestion of Jean-Pierre Melville) to remove several scenes from the feature using jump cuts, as they were filmed in one long take. Parts that did not work were simply cut from the middle of the take, a practical decision and also a purposeful stylistic one.

The cinematic stylings of French New Wave brought a fresh look to cinema with improvised dialogue, rapid changes of scene, and shots that go beyond the common 180° axis. The camera was used not to mesmerize the audience with elaborate narrative and illusory images, but to play with the expectations of cinema. The techniques used to shock and awe the audience out of submission and were so bold and direct that Jean-Luc Godard has been accused of having contempt for his audience. His stylistic approach can be seen as a desperate struggle against the mainstream cinema of the time, or a degrading attack on the viewer’s supposed naivety. Either way, the challenging awareness represented by this movement remains in cinema today. Effects that now seem either trite or commonplace, such as a character stepping out of their role in order to address the audience directly, were radically innovative at the time.

Classic French cinema adhered to the principles of strong narrative, creating what Godard described as an oppressive and deterministic aesthetic of plot. In contrast, New Wave filmmakers made no attempts to suspend the viewer’s disbelief; in fact, they took steps to constantly remind the viewer that a film is just a sequence of moving images, no matter how clever the use of light and shadow. The result is a set of oddly disjointed scenes without attempt at unity; or an actor whose character changes from one scene to the next; or sets in which onlookers accidentally make their way onto camera along with extras, who in fact were hired to do just the same.

At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods, and were inspired by the generation of Italian Neorealists before them. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to the theatre.

At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods, and were inspired by the generation of Italian Neorealists before them. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to the theatre.

Finally, the French New Wave, as the European modern Cinema, is focused on the technique as style itself. A French New Wave film-maker is first of all an author who shows in its film his own eye on the world. On the other hand the film as the object of knowledge challenges the usual transitivity on which all the other cinema was based, “undoing its cornerstones: space and time continuity, narrative and grammatical logics, the self-evidence of the represented worlds.” In this way the film-maker passes “the essay attitude, thinking – in a novelist way – on his own way to do essays.”

The Left Bank, or Rive Gauche, group is a contingent of filmmakers associated with the French New Wave, first identified as such by Richard Roud. The corresponding “right bank” group is constituted of the more famous and financially successful New Wave directors associated with Cahiers du cinéma. Unlike the Cahiers these directors were older and less movie-crazed. They tended to see cinema akin to other arts, such as literature. However they were similar to the New Wave directors in that they practiced cinematic modernism. Their emergence also came in the 1950s and they also benefited from the youthful audience. The two groups, however, were not in opposition; Cahiers du cinéma advocated Left Bank cinema.

Left Bank directors include Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. Roud described a distinctive “fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking”, as well as an identification with the political left. The filmmakers tended to collaborate with one another, Jean-Pierre Melville, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and Marguerite Duras are also associated with the group. The nouveau roman movement in literature was also a strong element of the Left Bank style, with authors contributing to many of the films. Left Bank films include La Pointe Courte, Hiroshima mon amour, La jetée, Last Year at Marienbad, and Trans-Europ-Express.

-Wikipedia

PRODUCTION NOTES

Breathless was loosely based on a newspaper article that Truffaut read in The News in Brief. The real-life Michel Poiccard is based on Michel Portail and his American girlfriend and journalist Beverly Lynette. In November 1952 Portail stole a car to visit his sick mother in La Harve and ended up killing a motorcycle cop named Grimberg.

Truffaut worked on a treatment for the story with Chabrol, but they ended up dropping the idea when they could not agree on the story structure. Godard had read and liked the treatment and wanted to make the film. While working as a Press Agent at 20th Century Fox, Godard met producer Georges de Beauregard and told him that latest film was shit. De Beauregard hired Godard to work on the script for Pêcheur d’Islands. After six weeks Godard became bored with the script and suggested making Breathless instead. Chabrol and Truffaut agreed to give Godard their treatment and wrote de Beauregard a letter from the Cannes Film Festival in May 1959 agreeing to work on the film if Godard directed it. Truffaut and Chabrol had recently become star directors and their names secured financing for the film. Truffaut was credited as the original writer and Chabrol as the technical adviser. Chabrol later claimed that he only visited the set twice and Truffaut’s biggest contribution was convincing Godard to cast Liliane David in a minor role.

Godard wrote the script as he went along. Along with the real life Michel Portail, Godard based the main character on screenwriter Paul Gégauff, who was known as a swaggering seducer of women. Godard also named several characters after people he had known earlier in his life when he lived in Geneva.

Jean-Paul Belmondo had already appeared in a few feature films prior to Breathless, but he had no name recognition outside of France at the time Godard was planning the film. In order to broaden the film’s commercial appeal, Godard sought out a prominent leading lady who would be willing to work in his low-budget film. He came to Jean Seberg through her then-husband, Francois Moreuil, with whom he had been acquainted. Seberg agreed to appear in the film on June 8, 1959 for $15,000, which was one-sixth of the film’s budget. Godard ended up giving Seberg’s husband a small part in the film. During the production, Seberg privately questioned Godard’s style and wondered if the film would be commercially viable. After the film’s success, she collaborated with Godard again on the short Le grand escroc, which revived her Breathless character.

Godard had initially wanted cinematographer Michel Latouche to shoot the film after having worked with him on his first short films. De Beauregard hired Raoul Coutard instead, who was under contract to him.

Godard envisaged Breathless as a reportage (documentary), and tasked cinematographer Raoul Coutard to shoot the entire film on a hand-held camera, with next to no lighting. In order to shoot under low light levels, Coutard had to use Ilford HPS film, which was not available as motion picture film stock at the time. He therefore took 18 metre lengths of HPS film sold for 35mm still cameras and spliced them together to 120 metre rolls. During development he pushed the negative one stop from 400 ASA to 800 ASA. The size of the sprocket holes in the photographic film was different than the sprocket holes for motion picture film and the Cameflex camera was the only camera that would work for the film used.

The production was filmed on location in Paris during the months of August and September in 1959, using an Eclair Cameflex. Almost the whole film had to be dubbed in post-production because of the noisiness of the Cameflex camera and because the Cameflex was incapable of synchronized sound.

Filming began on August 17, 1959. Godard met his crew at the Notre Dame cafe near the Hôtel de Suède and shot for two hours until he ran out of ideas. Coutard has stated that the film was virtually improvised on the spot, with Godard writing lines of dialogue in an exercise book that no one else was allowed to look at. Godard would give the lines to Belmondo and Seberg while having a few brief rehearsals on scenes involved, then filming them. No permission was received to shoot the film in its various locations (mainly the side streets and boulevards of Paris) either, adding to the spontaneous feel that Godard was aiming for. However all locations were picked out before shooting began and Assistant Director Pierre Rissient has described the shoot as very organized. Actor Richard Balducci has stated that shooting days ranged from 15 minutes to 12 hours, depending on how many ideas Godard had that day. Producer Georges de Beauregard wrote a letter to the entire crew complaining about the erratic shooting schedule. Coutard claims that on a day that Godard had called in sick de Beauregard bumped into the director at a cafe and the two got into a fist fight.

Godard shot most of the film chronologically, with the exception of the first sequence which was shot towards the end of the shoot. Filming at the Hôtel de Suède for the lengthy bedroom scene between Michel and Patricia included a minimal crew and no lights. This location was difficult to secure, but Godard was determined to shoot there after having lived at the hotel after returning from South America in the early 1950s. Instead of renting a dolly with complicated and time-consuming tracks to lay, Godard and Coutard rented a wheelchair for the film that Godard often pushed himself. For certain street scenes Coutard would hide in a postal cart with a hole in it for the lens and stamped packages piled on top of him. Shooting lasted for 23 days and ended on September 12, 1959. The final scene where Michel is shot in the street was filmed on the rue Campagne-Premiere in Paris.

Breathless was processed and edited at GTC Labs in Joinville with lead editor Cécile Decugis and assistant editor Lila Herman. Decugis has said that the film had a bad reputation before its premiere as the worst film of the year.

Coutard said that “there was a panache in the way it was edited that didn’t match at all the way it was shot. The editing gave it a very different tone than the films we were used to seeing. The film’s use of jump cuts has been called innovative. Andrew Sarris analyzed it as existentially representing “the meaninglessness of the time interval between moral decisions.” Rissient said that the jump cut style was not intended during the film’s shooting or the initial stages of editing.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

The opening of Breathless is “unprecedented,” in that we never learn what route brought Michel Poiccard to the Vieux Port of Marseille, where he surveys the future from the very edge of France. This first shot strikes a match to touch off an oil fire that will race through the film’s incidents and images, indeed through the New Wave altogether. A girlie tabloid filling the screen slips down to reveal the face of Jean-Paul Belmondo, cigarette dangling from his lips, as he looks out from under his rakishly cocked hat. His head swivels, and he rubs those lips with his thumb; he is ready for action. At a signal from a female accomplice, he hot-wires a big Oldsmobile just parked by an American military man touring with his wife. Abandoning the girl, who begs to be taken along, Poiccard drives off, exhaling in the flush of freedom, “Maintenant je fonce, Alphonse!” We can feel Godard’s own outlaw freedom in this sequence, carjacking a Hollywood genre and putting it into drive. The film lurches forward as he shifts up with wild shot changes; it charges ahead (il fonce) on bursts of music and sound effects, and on Belmondo’s spontaneous speeches, directed right to the camera, to us. Character and auteur will gun down the French authorities when stopped for questioning. From Marseille, Poiccard makes his way to Paris, to the Cathedral of Notre Dame and the Latin Quarter, then to the Champs-Élysées and its movie theaters (right under the offices of Cahiers du cinéma), where he shares the street with the crowds cheering Charles de Gaulle, head of the brand-new Fifth Republic. He will wind up in Montparnasse, on the rue Campagne-Première, the legendary street where Kiki hung out, as did Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Yves Klein. Breathless brings anarchy into the heart of Paris.

Auteur will meet character midway through the film, when Godard comes out into the open. Playing a concerned citizen, he exchanges suspicious glances with Poiccard, both from behind their newspapers and sunglasses. The filmmaker then reroutes the action by literally directing the police to the quarry that has eluded them. As Poiccard’s stolen car pulls out of frame, ominous music rises and an iris closes around Godard, who is seen fingering his hero to the cops. Genre will have its revenge in the final third of the film. And so we must ask: did Godard take himself to be an anarchic force, working his way from the outside into Paris, where he would flout the rules for the fun of it, or did he play the conscience of the art form, the critic who would reinvent the cinema by channeling the original energy of D. W. Griffith, Abel Gance, and Monogram Pictures that he plugged into at the Cinémathèque?

Either way, the verdict, rendered immediately, still holds: Breathless is the definitive manifesto of the New Wave. The movement was well under way when Godard made his entrée. In a much-discussed 1957 inquest, the popular weekly L’express had dubbed the ascendant generation “la nouvelle vague.” That generation’s pleasures, mores, and anxieties had been elaborated in the juicy novels of Françoise Sagan, particularly Bonjour tristesse, the best seller she wrote as a teenager, adapted by Otto Preminger in 1958 and starring Jean Seberg. As for the cinema, Godard was the very last of the notorious five Cahiers du cinéma critics to start a feature. Claude Chabrol had come out with two successes even before the triumph of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour at Cannes in spring 1959. But Breathless sealed the movement, defining it as simultaneously aggressive and nonchalant, adolescent and sophisticated. It did so through the behavior of its characters and its style, which, I insist, are linked.

Every criminal leaves traces of a style, a signature, as does every strong filmmaker. In Breathless, Belmondo gave to his character an engaging, if despicable, insouciance that resonated with Godard’s unapologetic way of making the film. Subject and style amplified each other. Belmondo provided calculated gestures—the thumb on the lips, the grimaces—and impulsive acts, such as shooting the cop or jumping out of a cab so he can win a sexist point by flipping the skirt of an unsuspecting pedestrian. He flips Seberg’s skirt too, just to provoke a reaction, enjoying her slap on his face. To these correspond the nervous jump cuts with which Godard gooses many of the film’s sequences, startling the audience each time. But the film’s audacious novelty is equally due to its superlong takes. Excessive especially by fifties standards, these decelerate the restless pace and make us watch for whatever may or may not happen next. Some shots last two, even three minutes. Not only does this match Poiccard’s impatient situation, waiting for acquaintances to show up for rendezvous, or for Patricia to get off work, or for phone calls from intermediaries; it also expresses his fundamental moral sloth, his fatigue, his death drive. Composer Martial Solal perfectly caught this bipolar aesthetic with two distinctive leitmotifs. And in repeating each theme close to a dozen times, Godard effectively detached the music from the plot, making it instead a palpable part of the film’s overall layout, its structure. Breathless absorbs the viewer not because it represents an engrossing story but because of the way it plays out that story. Thus Michel Poiccard fascinates us less than does Belmondo the irrepressible young actor coming into such a role. And Jean Seberg, though a well-known ingenue (particularly at Cahiers du cinéma, on whose cover she appeared in February 1958), likewise plays at finding her character—perhaps at finding herself, an American in Paris—as she adopts pose after pose for close-ups that come to make up 20 percent of the film. Similarly, the editing and music constitute elements as well as signifiers of tone and rhythm, visually and aurally structuring our experience.

When the turmoil conveyed by his young actors is insufficient to express the anxiety at the film’s core, Godard reveals his ambition, expressed in some of his earliest essays, to change the standard relation of editing to mise-en-scène, involving both cutting in the traditional sense and percussive effects within continuous takes. In a remarkable review late in 1958, he praised Alexandre Astruc’s Une vie for overturning, indeed for outrunning, standard expressions of violence created through “premeditated” editing, of the sort that whenever “a shot changed, a door opened, a glass shattered, a face turned.” Instead, in Une vie, even within its long tracking shots “the effect becomes almost the cause. The beauty is not so much in [Christian] Marquand’s dragging Maria Schell out of the château but in the abruptness with which he does it. This abruptness of gesture, which gives a fresh impulse to the suspense every few minutes, this discontinuity latent in continuity, might be called the telltale heart of Une vie.” Godard had already internalized the feeling, the drive, he would impart to Breathless.

As was the case with the similarly heralded Citizen Kane, Breathless’s audacious intervention in film history depended not just on the novelty or ambition of its debutant director but on his and his cast and crew’s technical genius. Take Martial Solal: his reputation in Paris jazz circles had led Jean-Pierre Melville to sign him on just a year earlier for Two Men in Manhattan, and he used him again in 1961 for Léon Morin, prêtre (starring Belmondo). Between these Solal worked simultaneously on Breathless and Jean Cocteau’s Testament of Orpheus, a film mentioned by Melville’s character during the Orly interview with Seberg in Breathless. Godard knew that in Solal he had a world-class pianist, and so, during editing, he asked him for improvisations. Along with the Chopin that Patricia puts on the record player, these piano elements are interspersed through the lengthy hotel room scene for the range and rhythm they help structure. Or take Belmondo. How comfortable he is with Godard’s tempo as he shows off his tics and playfulness (the shadowboxing). Raoul Coutard’s camera trains itself on him and Seberg during the long takes in the cramped hotel, when the subject is nothing other than time passing between two people. Coutard, relatively new to feature films himself, immediately became Godard’s prosthetic hand and eye, remaining so for more than twenty years and fourteen films. Working as a Paris match war photographer in Indochina throughout the fifties, he had learned to capture his target, no matter what the conditions, and to do so without trampling on the subject. For Breathless, he was ingenious, feeding countless rolls of still-camera negative into magazines for the Éclair Caméflex, concocting a new developer to double the sensitivity of the film, rigging makeshift dollies for the candid-camera tracking shots on Paris thoroughfares, manipulating available light to give Godard and his actors range and immediacy.

Other first films (including many of today’s indies) exude the sparkling joy of filmmaking that one feels in Breathless, but how many can boast its sure-handedness? It is said that Godard never betrayed indecision on the set, even if he may sometimes have scribbled or shouted dialogue at the moment of shooting. He had prepared himself for a decade, during his so-called amateur phase. First of all through criticism, an activity that he has always maintained was a way of making films without a camera. Then he had helped his Cahiers du cinéma colleagues on their short films and watched them move into features, playing bit roles for Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette. He had made one industrial film on commission, along with several shorts of his own. In the late fifties, he edited animal documentaries and travelogues and was hired to write dialogue for features. While serving as Fox’s Paris press agent and promoter, he met producer Georges de Beauregard, who was impressed enough with him to put him to work. De Beauregard would soon give him the chance he begged for, picking the brief story outline of Breathless from among several projects Godard put before him. It surely helped that Truffaut, who had just caused a sensation at Cannes with The 400 Blows, was the source of the idea for Breathless and that Chabrol agreed to serve as technical adviser. De Beauregard could take a chance on his haughty assistant because the laws governing subsidy had recently changed, and first-time directors were eligible to receive funds. Moreover, they were cheap and now carried a certain cachet. Godard seethed at having to use the names of his friends, even though they both understood he was on his own. He considered himself so experienced in the industry that he would scorch it with his first feature.

It took the pretentiousness of youth to flaunt the idea of a revivified cinema in the stone face of an even more pretentious establishment. Godard’s writings have always sounded brash and pugnacious, yet his earliest articles often sang the purity of artistic expression. Poe, Baudelaire, and Rimbaud were his models. He could write without irony, “What is difficult is to advance into unknown lands, to be aware of the danger, to take risks, to be afraid.” Breathless announces this as its principal theme early on, when Poiccard passes a movie poster advertising Robert Aldrich’s Ten Seconds to Hell: “Live Dangerously Until the End!” Godard believed that the powerful writers of the past (Stendhal, for instance, who provided the epigraph for Godard’s scenario) would surely have been auteurs of cinema in the mid-twentieth century. Long before Gilles Deleuze, Godard called on popular genres—the musical, the western, and of course the film noir—to address the philosophical issues of his day. Sartre, after all, had worked in film, as had Malraux, now minister of culture and the man who lent his personal support to get The 400 Blows to Cannes. In blaring the triumph of that film, Godard compared the dangerous gleam in the eye of Antoine Doinel to that in the eye of Tchen, the suicidal terrorist who opens Malraux’s La condition humaine, as he plunges his knife into a sleeping body. Merciless and intrepid, Godard took himself to be a loner even within the Cahiers du cinéma clan, tying genuine art to courage and solitude. “The cinema is not a craft. It is an art. It does not mean teamwork. One is always alone on the set as before the blank page. And to be alone?.?.?. means to ask questions. And to make films means to answer them. Nothing could be more classically romantic.”

The “authenticity” demanded by Godard’s existentialist ardor he found in the three filmmakers who were his principal models: Nicholas Ray, Roberto Rossellini, and Jean Rouch. Ray embodied that “classically romantic” soul at war in Hollywood. “If the cinema no longer existed,” Godard wrote, “Nicholas Ray alone gives the impression of being capable of reinventing it, and what is more, of wanting to.” Ray’s first marvelous effort, They Live by Night, sets moments of unforgiving documentary technique alongside the fresh and painfully sensitive faces of Cathy O’Donnell and a young Farley Granger, who, like Belmondo, is gunned down in the final scene. Ray came to Paris in the late fifties and, when interviewed by Cahiers du cinéma, played right into Godard’s rhetoric: “My personal trademark has always been ‘I’m a stranger here myself’ . . . The quest for a fulfilled life is, I think, paradoxically solitary.” Breathless tries on such full-out romanticism, and likes the feel of it here and there; nevertheless, glancing at itself too often in the mirror, the film stares down this sentiment, and indeed itself, with irony.

Rossellini had been introduced to the Cahiers du cinéma équipe by André Bazin, and although it was Truffaut who served as the Italian filmmaker’s assistant from 1954 to 1957, Godard did discuss projects with him too. Breathless has been compared to Rossellini’s Rome Open City as a star-driven melodrama checked by its director’s tough urban neorealism. But I would highlight Machine to Kill Bad People, for its disorienting mixture of tones, its offhand cultural citations, and its direct reflections on cinema and death. Finally, Voyage to Italy, the masterpiece whose themes Godard would reprise in Contempt, can already be felt in Poiccard’s desire to take Patricia to Italy in a big car. But beyond film references, Rossellini inspired Godard to shoot quickly, to interrupt shooting when inspiration flagged, to use notes rather than a script, and to devise cheap technical solutions to logistical problems. Godard had originally slated Rossellini instead of Melville to play Parvulesco. And two years later, Godard would use Rossellini’s incendiary theater piece Les carabiniers as the basis for his film of that name.

The Godard-Rouch connection is increasingly obvious today. Just two months before he pitched Breathless to de Beauregard, Godard wrote, “Moi, un noir is the most daring and humblest of films . . . less perfect as cinema than many other current films . . . [yet] it makes all of them not only useless but almost odious . . . In calling his film Moi, un noir, Jean Rouch, who is white like Rimbaud, is saying like him, ‘I is Another.’ Thus his film is an open sesame to poetry.” Godard would immediately adopt Rouch’s crude aesthetic of handheld ethnographic camera, dubbed soundtrack, stories told by characters, throwaway film references (characters called Lemmy Caution, Dorothy Lamour, and Edgar G. Robinson), and an overall smart-aleck tone in which cinephilia meets up with documentary. Breathless could almost be called Chronicle of a Summer, the title Rouch would give his Paris essay filmed on many of the same streets and in the same manner twelve months later.

Uncomfortable with himself and allergic to much of postwar life, especially cinema, Godard would produce in Breathless the kind of aesthetic friction he felt in Ray, Rossellini, and Rouch, a friction that spilled over into their intransigent relations with producers and the larger public. All four were taken as difficult and disagreeable, representing the acerbic side of modernism, its refusal to please (or at least to do so easily). Breathless is indeed a hallmark of modernist cinema, as well as of modernism tout court. Godard forced the kind of confrontation between high and popular culture that energized the art world (Yves Klein, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein). Ingeniously, he scripted a chiasmus where an American girl is left to guard traditional artistic values (Bach, Chopin, Mozart, Renoir, Matisse, Picasso, Faulkner) while the Frenchman, a reader only of newspapers, is a connoisseur of cars, particularly American ones. Cinematic modernism reaches a plateau when, while a crowd cheers Eisenhower and de Gaulle along the Champs-Élysées, the characters give the slip to the cops by hiding out in a movie theater that is playing Budd Boetticher’s Westbound. Michel and Patricia tenderly kiss in the dark against the violent sounds of the movie, but with Godard himself reciting a love poem by Louis Aragon as if it were Boetticher’s dialogue. The dramatic heat produced when distinct national cultures (both high and low) rub up against each other energized not just this corrosive movie but an entire movement, vigorous and critical: the nouvelle vague.

With Breathless, Godard forged to the front of this New Wave, which over the following half dozen years he would push beyond the breaking point, until he abandoned all vestiges of commercial filmmaking in the climate that produced the events of 1968. In his subsequent Dziga Vertov Group period, he recanted the aesthetic libertarianism that had made Breathless complicit, he intimated, with Michel Poiccard’s right-wing anarchism, and thus unwittingly an effect of bourgeois capitalist ideology. In 1975, having emerged from his most militant Maoist phase, Godard talked de Beauregard into helping underwrite a new project, Numéro 2: À bout de souffle. Ostensibly to commemorate their triumph fifteen years earlier, they determined, as a gimmick, that the new film’s budget would match that of its inexpensive predecessor. Godard referred to it as his “second first film,” completing what came to be called simply Numéro deux with Anne-Marie Miéville, for their company Sonimage. Despite the essay format it adopts instead of a plot, and despite the extensive use of video technology, Godard would continue to claim it as a remake of Breathless, if only to provoke viewers into interrogating both films. Although historian Michel Marie writes that their cost is the only thing that Breathless and Numéro deux share, I would claim that the latter abstracts the gender and media oppositions that gave Breathless such energy and pertinence.

More recently, Godard honored his first feature by making it an index of the century’s middle period. In a brief video essay that he put together in 2000 and called L’origine du XXIème siècle, Godard superimposed disturbing newsreel footage and clips from fiction films, in a time line broken into intervals of fifteen years. He grouped an extended montage of horrors around the title card “1975” and an equally ample series after “1945.” Between these he inserted but a single shot to stand for the period designated “1960”: Jean Seberg, nearly catatonic, thumb against lips, asks no one in particular, or asks us: “Qu’est-ce que c’est ‘dégueulasse’?” (the final line of Breathless). A symptom that he refuses to disown, Breathless is also a film and a stage that Godard and history have gone beyond. Yet even in his complex later works, Godard returns to the contradictions he fixed so indelibly in 1960, though increasingly through the lens of memory-images and historiography. Breathless is one of Godard’s (and our culture’s) reflex images, so acute and apt that it remains sharply in focus for anyone who cares about the cinema, about the West in 1960, or about ourselves at the onset of the twenty-first century.

-Dudley Andrew

What makes the bedroom sequence scene brilliant and revolutionary is the dialog between these two lovers because it feels so fresh and natural and it flows so smoothly. The banter between them, even though is pointless and rather idiotic is so spontaneous and feels organic and unrehearsed that you can see why this film probably related to a lot of younger people. The way it portrays the narcissistic youth who are obsessed with themselves and oblivious to the real world is something that no one had ever witnessed in cinema before. Yet it is all relatable and interesting because this is how many young people speak to each other (I sure didn’t) and you can see where director Quentin Tarantino developed his style of pointless banter between characters who were also oblivious to what was going on outside their criminal lifestyle. In this bedroom scene and throughout the film, Godard uses jump cuts, cuts within continuous movement or dialogue, trying no attempts at all to make them match. The technique “was a little more accidental than political,” writes the Australian critic Jonathan Dawson. The finished film was 30 minutes longer then Godard wanted, and rather than cut out whole scenes or sequences, Godard elected to trim within the scene, creating the jagged cutting style still so beloved of current action filmmakers. Godard just went at the film with the scissors, cutting out anything he thought boring.

Godard’s cinematographer in Breathless was Raoul Coutard and the methods he used became as groundbreaking as the methods that D.W. Griffith developed in The Birth of a Nation. Since this was a low-budget independent film they couldn’t afford tracks for a tracking shot so instead Coutard held the camera and was pushed in a wheelchair. He developed hand-held techniques before lightweight cameras were even invented, and made the film look grainy which other filmmakers followed to make their films look more realistic. Film critic Roger Ebert said, “He even created newly developed lighting techniques and there is a classic back-lit of Belmondo in bed and Seberg sitting beside the bed, both smoking, the light from the window enveloping them in a cloud.”

Breathless and the iconic character of Michel is what made Jean-Paul Belmondo become an international star and he became the biggest French star between Jean Gabin and Gerard Depardieu. Michel is a cocky arrogant fool who has yet got his comeuppance, which is exactly what his character needs to wake up and see the real world for what it is. (I guess you can say he does receive it in the end.) Michel tries to front this touch-guy exterior which resembles the movie stars he sees in the movies, but all he comes off being is a scared, weak and desperate young man. His macho persona is a performance to conceal a lost soul who sadly doesn’t even know himself. Michel’s shootout with the cops and death in the street is more of an homage to the American classic gangster films, and in many ways Michel gets an ending that he has always dreamed of. There’s a scene outside of a theatre where Michel is looking at a poster of actor Humphrey Bogart, adoring his idol and blowing smoke at the poster while rubbing his lips with his thumb. In one sequence Michel exaggeratingly knocks a man unconscious to steal his cash, obviously trying to reenact one of the many movies he so adores. Michel clearly has seen too many Hollywood American films and this dilluted thinking is what eventually leads him to an early grave.

Jean Seberg who plays the character of Patricia was restarting her career in Europe after failing in America. She fled to Europe, where she was only 21 where she happened upon Jean-Luc Godard who luckly decided to cast her for Breathless which made her an immediate star. I will never really understand the character of Patricia and what she could possibly see in a person like Michel. Michel is easy to read because he isn’t very bright, but Patricia is a smart educated young woman who likes the work of Picasso and Faulkner. Even when she finds out Michel is wanted for the murder of a police officer, has more than one name and that is still currently married, she still continues to stay with him, and you start to wonder what she could possibly be thinking to want to be around a man like that. When Patricia decides to betray Michel and finally alerts the authorities, she does it not because it’s the right thing to do, but because she wants to test herself to see if she truly loves him or not. She bravely informs Michel that she betrayed him, (which is stupid knowing Michel is capable of murder) which of course angers Michel; now knowing he has to get his money and flee the city. Critic Roger Ebert describes Patricia by saying, “It is remarkable that the reviews of this movie do not describe her as a monster–more evil, because she’s less deluded, than Michel.” There’s a moment in the film where Patricia is fleeing from a detective who is following her and she runs into a movie theatre and escapes through a back exit. This scene is a scene directly quoted in Bonnie and Clyde, where the movie that’s playing in the theatre directly reflects the film that were watching. In Bonnie and Clyde we hear “we’re in the money,” from the 30’s classic musical Golddiggers of 1933. In Breathless we hear the dialogue about a woman “covering up for a cheap parasite,” in Budd Boetticher’s Westboud. Is it merely a coincidence that Bonnie and Clyde was influenced by the French New Wave movement and not only is known to be the iconic film that started the rebellious youth culture of the late 60’s, but also was a film that both Godard and Truffaut were once asked to direct as well? When Breathless reached its 50th anniversary the New York Times stated, “Breathless is both a pop artifact and a daring work of art and even at 50, still cool, still new, still – hip after all this time! – a bulletin from the future of movies”. Breathless ranked as the No. 15 best film of all time in the British Film Institute’s 2002 Sight and Sound Critics’ Poll. Jean-Luc Godard is considered one of the most important filmmakers in the world and when most people think of his films they think of Breathless. Other masterpieces he created over the years was a film called Contempt which is about a writer involved in the movie industry ordered to write a screenplay of Ulysses, (where Fritz Lang makes a cameo playing himself.) Alphaville is a neo noir sci-fi thriller and then there’s Vivre Sa Vie, where Anna Karina plays a woman who slowly descents into prostitution. Band of Outsiders is considered somewhat a companion piece to Breathless; which involves a memorable dance sequence and Pierrot Le Fou was Godard’s colorful farewell to the gangster genre and yet mixes in several other genres as well. Godard later on started making films which were more political essays and full of collage like images that were very philosophical like in Masculine Feminin, 2 or 3 Things I know about Her and his abstract surreal film Weekend. Breathless had a sensational reception when released and it was safe to say that the cinema was permanently changed. When Breathless became a commercial success several young directors saw it as a chance to finally abandon the traditional studio and start making movies from the beginning. It was like Godard and all the young French filmmakers from the ‘Cahiers du cinema’ magazine threw out the ‘How to make a movie’ pamphlet and started from scratch, rewriting and redesigning fresh new ways to construct a movie and to tell a great story. These new invented film techniques occur very rarely in the history of film and it started in the early 1900’s with the films from D.W. Griffith which then led to Welles in the 40’s, Godard in the 60’s and now what Tarantino did when making Pulp Fiction in the 90’s.