Battleship Potemkin (1925)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Battleship Potemkin Sergei Eisenstein” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Sergei Eisenstein’s revolutionary propaganda film Battleship Potemkin is one of the fundamental landmarks in the history of the cinema. Critics, film scholars and movie directors over the years have endlessly quoted and referenced the film, that most younger viewers most likely have seen the parody before seeing the original. Upon its original release Battleship Potemkin was banned in it’s native Soviet Union and throughout several countries because many believed the power of its images would actually incite audiences to real political violence. The movie was even ordered up by the Russian revolutionary leadership for its 20th anniversary of the Potemkin uprising, which Lenin had hailed as the first proof that troops could be counted on to join the proletariat in overthrowing the old order. Unfortunately when watching the film today much of that original power doesn’t seem to be as effective, as film critic Roger Ebert points out, “probably because its shocking images have warn out its element of surprise…that, like the 23rd Psalm or Beethoven’s Fifth, it has become so familiar we cannot perceive it for what it is.” Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein was a student of the Kuleshov school of film-making and advocate of the theories of Soviet montage, which were a series of shots that formed conflict, collision and shock, which he believed was much more effective in emotionally affecting the viewer. Doing this Eisenstein would manipulate the viewer in feeling sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and hatred for their cruel overlords. Eisenstein also experimented with a theory called Intellectual Montage which was considered a style of editing that could form a relation or meaning between two separate images created from juxtaposition, and have them form new ideas, metaphors or symbols to the shots. These theories were greatly used in the infamous Odessa Staircase massacre sequence, as he cuts between the frightened faces of the unarmed citizens, to the faceless troops with weapons, creating an contrasting argument for the people against the tyranny of the tsarist/czarist state. [fsbProduct product_id=’738′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Since its release in 1925, Battleship Potemkin has often been cited as one of the finest propaganda films ever made and considered amongst the greatest films in the world, usually listed besides such acclaimed films as Vittoria De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, Orson Welles Citizen Kane, Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, and Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. Even today, when viewing The Odessa Staircase massacre sequence with its chaotic use of editing and rhythm, it is still an emotionally draining experience for the viewer. Eisenstein’s brilliant use of Soviet Montage barely gives the viewer a chance to step back and breathe, as they watch in horror as a boy is horrifically trampled to death by of a fleeing mob of people, and soon afterwards his mother is brutally executed after begging for her son’s life. This violent and intense sequence can also be looked at as the aesthetic starting point which inevitably led to other thrilling sequences whether its Alfred Hitchcock’s shower sequence in Psycho or Sam Peckinpah’s bloody shoot-out in The Wild Bunch. Not only is Battleship Potemkin a brilliant example on the techniques of editing and propaganda, but it can give younger audiences a historical perspective on just how dangerous and controlling cinema can be as a medium.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Battleship Potemkin Sergei Eisenstein” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Sergei Eisenstein’s revolutionary propaganda film Battleship Potemkin is one of the fundamental landmarks in the history of the cinema. Critics, film scholars and movie directors over the years have endlessly quoted and referenced the film, that most younger viewers most likely have seen the parody before seeing the original. Upon its original release Battleship Potemkin was banned in it’s native Soviet Union and throughout several countries because many believed the power of its images would actually incite audiences to real political violence. The movie was even ordered up by the Russian revolutionary leadership for its 20th anniversary of the Potemkin uprising, which Lenin had hailed as the first proof that troops could be counted on to join the proletariat in overthrowing the old order. Unfortunately when watching the film today much of that original power doesn’t seem to be as effective, as film critic Roger Ebert points out, “probably because its shocking images have warn out its element of surprise…that, like the 23rd Psalm or Beethoven’s Fifth, it has become so familiar we cannot perceive it for what it is.” Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein was a student of the Kuleshov school of film-making and advocate of the theories of Soviet montage, which were a series of shots that formed conflict, collision and shock, which he believed was much more effective in emotionally affecting the viewer. Doing this Eisenstein would manipulate the viewer in feeling sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and hatred for their cruel overlords. Eisenstein also experimented with a theory called Intellectual Montage which was considered a style of editing that could form a relation or meaning between two separate images created from juxtaposition, and have them form new ideas, metaphors or symbols to the shots. These theories were greatly used in the infamous Odessa Staircase massacre sequence, as he cuts between the frightened faces of the unarmed citizens, to the faceless troops with weapons, creating an contrasting argument for the people against the tyranny of the tsarist/czarist state. [fsbProduct product_id=’738′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Since its release in 1925, Battleship Potemkin has often been cited as one of the finest propaganda films ever made and considered amongst the greatest films in the world, usually listed besides such acclaimed films as Vittoria De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, Orson Welles Citizen Kane, Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, and Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. Even today, when viewing The Odessa Staircase massacre sequence with its chaotic use of editing and rhythm, it is still an emotionally draining experience for the viewer. Eisenstein’s brilliant use of Soviet Montage barely gives the viewer a chance to step back and breathe, as they watch in horror as a boy is horrifically trampled to death by of a fleeing mob of people, and soon afterwards his mother is brutally executed after begging for her son’s life. This violent and intense sequence can also be looked at as the aesthetic starting point which inevitably led to other thrilling sequences whether its Alfred Hitchcock’s shower sequence in Psycho or Sam Peckinpah’s bloody shoot-out in The Wild Bunch. Not only is Battleship Potemkin a brilliant example on the techniques of editing and propaganda, but it can give younger audiences a historical perspective on just how dangerous and controlling cinema can be as a medium.

PLOT/NOTES

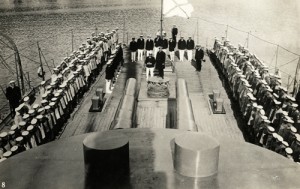

The film celebrates the dramatized true story of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin rebelled against their officers of the Tsarist regime.

The film is composed of five episodes:

- “Men and Maggots”, in which the sailors protest at having to eat rotten meat;

- “Drama on the Deck”, in which the sailors mutiny and their leader, Vakulinchuk, is killed;

- “A Dead Man Calls for Justice”, in which Vakulinchuk’s body is mourned over by the people of Odessa;

- “The Odessa Staircase”, in which Tsarist soldiers massacre the Odessans.

- “The Rendez-Vous with a Squadron”, in which the squadron tasked with intercepting the Potemkin instead declines to engage, lowering their guns, its sailors cheer on the rebellious battleship and join the mutiny.

The film opens as the crew members of the battleship, cruise the Black Sea after returning from the war with Japan. Sailors on the battleship are given maggot-infested food to eat. There is a disgusting close-up of their breakfast meat, crawling with maggots and dead larvae as the ship doctor examines it. “We’ve had enough rotten meat! Even a dog wouldn’t eat it,” shouts one of the sailors saying that Russian prisoners in Japan are fed better than them. Senior Officer Giliarovsky orders all the workers up on deck and announces: “Whoever is satisfied with the borscht take two steps forward! You’re free to go! I’ll hang the rest on the yard!”

There is an interesting shot where the convicted soldiers look up and imagine ghostly figures hanging from the yard. The firing squad raises there guns and is about to follow Officer Giliarovsky’s orders until a firebrand named Vakulinchuk steps forward and cries out, “Brothers! Who are you shooting at?” The firing squad lowers their guns, and when an officer unwisely tries to enforce his command, full-blown suddenly mutiny takes over the ship. The sailors attack the officers and gain control of the ship, although Vakulinchuk is killed by a senior officer.

Onshore, news of the uprising reaches citizens who have long suffered under czarist repression. They send food and water out to the battleship in a flotilla of skiffs. The sailors decide to take Vakulinchuk to the port city of Odessa, where his body serves as a heroic symbol of those who would give their lives for the revolution. Citizens come out to pay respect and offer their support for the Potemkin, as there is an extraordinary shot of the camera panning up to reveal a line of hundreds of people.

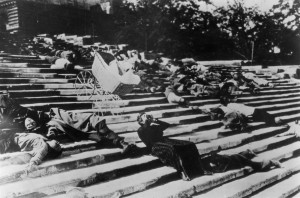

Then, in one of the most famous sequences ever put on film, czarist militia arrive in white tunics and march down the Odessa Steps (also known as the Primorsky or Potemkin Stairs), which is a long a seemingly endless flight of steps in a rhythmic, machine-like fashion, firing into the crowds of citizens who flee before them in a terrified tide. A separate detachment of mounted Cossacks also are charging the crowd at the bottom of the stairs. The whole massacre is summed up with iconic victims which include a nurse wearing Pince-nez, a young boy with his mother, a student in uniform and a teenage schoolgirl. A mother trying to protect her infant in a baby carriage is also shot dead and falls to the ground and the carriage rolls and bounces down the steps amidst the fleeing out of control crowd.

News of the uprising reaches the Russian fleet, and so the battleship responds by speeding toward Odessa to fire at the headquarters of the tsarist generals who are located onshore nearby. A squadron destroyer which is commanded by the tsarist’s is sent out to stop the Potemkin and so the Potemkin decide to sail out and face it. Eisenstein creates slow rising tension by cutting between the approach fleet, the brave Potemkin, and details of the on-board preparation as the Potemkin readies their cannons and gets in firing position.

At the last moment, the two battleships approach one another and the men of the Potemkin signal their comrades in the fleet to join them: “Don’t fight us…join us.” On the verge of a oncoming battle a title card suddenly reads, “Brothers!” and sailor on both ships unite and celebrate as the Potemkin steams pass without a shot being fired and now with added support among the oncoming ships without a shot being fired at it, the rebellious battle-ship passed through the rows of the squadron.

SOVIET MONTAGE

Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein wrote Battleship Potemkin originally as a revolutionary propaganda film, but also to test his theories of Soviet Montage. Montage is a synonym for a form of editing which was practiced by Soviet filmmakers Lev Kuleshov, Vesvolod Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein around the 1920s at the Kuleshov school of film-making. Each filmmaker incorporated their own forms and ideologues of Soviet Montage differently into their films under the teachings of Lev Kuleshov, placing these ideas into political concepts. Eisenstein called these different forms ‘Cinema of Attractions’ and experimented with a form of film editing which attempted to produce the greatest emotional response in a viewer by conflicting two different shots side created from juxtaposition. Soviet Montagists took the work of editing away from mere exposition and focused on materialization of ideas, motifs, symbols, metaphors, themes, and concepts through editing.

In formal terms, Soviet Montage’s style of editing offers discontinuity in graphic qualities, violations of the 180 degree rule, and the creation of impossible spatial matches. It is not concerned with the depiction of a comprehensible spatial or temporal continuity as is found in the classical Hollywood continuity system. It draws attention to temporal ellipses because changes between shots are obvious, less fluid, and non-seamless.

Eisenstein describes five methods of montage in his introductory essay ‘Word and Image’. These varieties of montage build one upon the other so the higher forms also include the approaches of the “simpler” varieties. In addition, the “lower” types of montage are limited to the complexity of meaning which they can communicate, and as the montage rises in complexity, so will the meaning it is able to communicate (primal emotions to intellectual ideals). It is easiest to understand these as part of a spectrum where, at one end, the image content matters very little, while at the other it determines everything about the choices and combinations of the edited film.

Eisenstein’s montage theories are based on the idea that montage originates in the “collision” between different shots in an illustration of the idea of thesis and antithesis. This basis allowed him to argue that montage is inherently dialectical, thus it should be considered a demonstration of Marxism and Hegelian philosophy. His collisions of shots were based on conflicts of scale, volume, rhythm, motion (speed, as well as direction of movement within the frame), as well as more conceptual values such as class.

- Metric – where the editing follows a specific number of frames (based purely on the physical nature of time), cutting to the next shot no matter what is happening within the image. This montage is used to elicit the most basal and emotional of reactions in the audience.

- Metric montage example from Eisenstein’s October.

- Rhythmic – includes cutting based on continuity, creating visual continuity from edit to edit.

- Rhythmic montage example from The Good The Bad and the Ugly where the protagonist and the two antagonists face off in a three-way duel

- Another rhythmic montage example from The Battleship Potemkin’s “Odessa steps” sequence.

- Tonal – a tonal montage uses the emotional meaning of the shots—not just manipulating the temporal length of the cuts or its rhythmical characteristics—to elicit a reaction from the audience even more complex than from the metric or rhythmic montage. For example, a sleeping baby would emote calmness and relaxation.

- Tonal example from Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin. This is the clip following the death of the revolutionary sailor Vakulinchuk, a martyr for sailors and workers.

- Overtonal/Associational – the overtonal montage is the cumulation of metric, rhythmic, and tonal montage to synthesize its effect on the audience for an even more abstract and complicated effect.

- Overtonal example from Pudovkin’s Mother. In this clip, the men are workers walking towards a confrontation at their factory, and later in the movie, the protagonist uses ice as a means of escape.

- Intellectual – uses shots which, combined, elicit an intellectual meaning.

- Intellectual montage examples from Eisenstein’s October and Strike. In Strike, a shot of striking workers being attacked cut with a shot of a bull being slaughtered creates a film metaphor suggesting that the workers are being treated like cattle. This meaning does not exist in the individual shots; it only arises when they are juxtaposed.

- At the end of Apocalypse Now the execution of Colonel Kurtz is juxtaposed with the villagers’ ritual slaughter of a water buffalo.

Intellectual Montage would make the viewer think more deeply about the connection between two separate images having them form new ideas, metaphors or symbols to the shots. The general trajectory between Intellectual Montage is Perception, Emotion, and Cognition. Eisenstein’s theory was based on a Japanese ideogram in which he created a third meaning within two separate shots which were the sum of all greater parts. For instance, a shot of a bird and a mouth would form a third meaning to the viewer which was to sing. The shots of an eye and water would form meanings of crying and the shots of a baby and a mouth would form the meaning of screaming. Drawn from the Marxist philosophical precept in which Dialectics=Thesis & Antithesis which = Synthesis. For example: Bourgeois/tsarist (thesis)+proletariat (antithesis)=outcome of classless society/revolution (synthesis).

Eisenstein’s style of Intellectual Montage is very similar to Kuleshov’s original theory called the Kuleshov Effect. The Kuleshov Effect was a experiment demonstrated in the 1910s and 20s where filmmaker’s recutted old footage of a close-up of actor Ivan Mozhuchin and repeatedly cut shots of other material like a bowl of soup, a crying baby or a dead woman’s body. Audiences would look at the same footage of Ivan Mozhuchin followed by a different shot and would bring a different conclusion to what they had to say about the scene. Eisenstein’s Intellectual Montage brought the power of editing to an even greater level and not only had the audience create different conclusions on what they saw on the screen, but they would create deeper symbolic meanings and metaphors that went outside the context of the film.

In his later writings, Eisenstein argues that montage, especially intellectual montage, is an alternative system to continuity editing. He argued that “Montage is conflict” (dialectical) where new ideas, emerge from the collision of the montage sequence (synthesis) and where the new emerging ideas are not innate in any of the images of the edited sequence. A new concept explodes into being. His understanding of montage, thus, illustrates Marxist dialectics.

Concepts similar to intellectual montage would arise during the first half of the 20th century, such as Imagism in poetry (specifically Pound’s Ideogrammic Method), or Cubism’s attempt at synthesizing multiple perspectives into one painting. The idea of associated concrete images creating a new (often abstract) image was an important aspect of much early Modernist art.

Concepts similar to intellectual montage would arise during the first half of the 20th century, such as Imagism in poetry (specifically Pound’s Ideogrammic Method), or Cubism’s attempt at synthesizing multiple perspectives into one painting. The idea of associated concrete images creating a new (often abstract) image was an important aspect of much early Modernist art.

Eisenstein relates this to non-literary “writing” in pre-literate societies, such as the ancient use of pictures and images in sequence, that are therefore in “conflict”. Because the pictures are relating to each other, their collision creates the meaning of the “writing”. Similarly, he describes this phenomenon as dialectical materialism.

Eisenstein argued that the new meaning that emerged out of conflict is the same phenomenon found in the course of historical events of social and revolutionary change. He used intellectual montage in his feature films (such as Battleship Potemkin and October) to portray the political situation surrounding the Bolshevik Revolution.

He also believed that intellectual montage expresses how everyday thought processes happen. In this sense, the montage will in fact form thoughts in the minds of the viewer, and is therefore a powerful tool for propaganda.

Intellectual montage follows in the tradition of the ideological Russian Proletcult Theatre which was a tool of political agitation. In his film Strike, Eisenstein includes a sequence with cross-cut editing between the slaughter of a bull and police attacking workers. He thereby creates a film metaphor: assaulted workers = slaughtered bull. The effect that he wished to produce was not simply to show images of people’s lives in the film but more importantly to shock the viewer into understanding the reality of their own lives. Therefore, there is a revolutionary thrust to this kind of film making.

Eisenstein discussed how a perfect example of his theory is found in his film October, which contains a sequence where the concept of “God” is connected to class structure, and various images that contain overtones of political authority and divinity are edited together in descending order of impressiveness so that the notion of God eventually becomes associated with a block of wood. He believed that this sequence caused the minds of the viewer to automatically reject all political class structures.

These five styles of Soviet Montage’s Cinema of Attractions has been influential for several future filmmakers’ as you still see forms of Soviet Montage being used in many present films today, most famously with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Pudovkin’s theory was in support of larger narrative action and of a series of linkage between shots. Vertov focused on rhythm in editing, and celebrated on how the eye of the camera recorded reality in contrast to the human eye. Sergei Eisenstein’s theory of montage is the most complex and most interesting of styles. Eisenstein developed three different forms of Montage. The first was Perceptual Montage which is a way of editing that would shock and affect the viewer. The second was Associational Montage which were comparisons or associations made through the sum of the shots.

One of the basic artistic precedents to the Soviet Montage movement was Russian Constructivism which was an art that fulfilled a clear social function and is not autonomous involving such artistic merits as architecture, graphic design and the theater. Constructivism incorporates the effect of technology and the industry on abstraction of forms such as the craftsman-worker (not genius or visionary.) The purity of geometric shapes such as lines and volumes communicates ideas more sharply, as the art becomes harnessed to social function and abstraction or utility. The artwork as machine within Constructivism counters the notion of art as organic, as art is seen as a synthesis between the dialectic nature and the industry/science which is seen in director Sergei Eisenstein’s writings. Constructivism refutes and challenges the notion of composition of passive decorative elements, which is a more direct construction of materials, or a manipulation of materials, as its component parts are activated and assembled, montage as “putting together.” The basic idea of Russian Constructivism is influenced by French Cubism & Italian Futurism, but these predecessors are not as overtly political as the Constructivist movement.

Russian Constructivism and these theories of Soviet Montages were greatly used in Battleship Potemkin, whether its the furious citizens yelling “Down with the tyrants!” and the shot is cut to clenched fists, or the captain threatening to hang mutineers from the yard, as the scene cuts to ghostly figures hanging from there. But the greatest uses of Soviet Montage are in the infamous Odessa Staircase massacre sequence, as director Sergei Eisenstein cuts between the frightened faces of the unarmed citizens, and then to the faceless troops with weapons, creating a contrasting argument for the people against the tsarist/czarist state. Other examples of this theory can be seen in this sequence whether its the defenseless civilians who are unable to flee and the cut to the citizen without legs, A military boot crushing a child’s lifeless hand and body and the horrifying reaction of the child’s helpless mother, a nurse with a pair of Pince-nez, but when the shot returns back to her the Pince-nez has been pierced by a bullet. And the most famous scene in this sequence (which was homaged most famously in Brian D Palma’s The Untouchables) when a mother is fatally shot while pushing an infant in a baby carriage and slowly falls to the ground pushing the baby carriage down the steps while it cuts to the violent slaughter of its fleeing crowd.

Eisenstein purposely used his editing techniques of Soviet Montage and the linkage and collision of shots as practical weapons as Eisenstein said in his own words: “solve the specific problem of cinema, and challenge audiences to experience ideas, emotions and sensations while being engrossed within a story.” Eisenstein put his techniques to full use with Battleship Potemkin, emotionally manipulating the audience in such a way as to feel sympathy for the rebellious sailors of the Battleship Potemkin and a emotional hatred for their cruel overlords. In the manner of most propaganda, the characterization is simple, so that the audience could clearly see with whom they should sympathize. The massacre on the steps, which never took place, was presumably inserted by Eisenstein for dramatic effect and to purposely demonise the Imperial regime.

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

In both the Soviet Union and overseas, Battle Potemkin shocked audiences, but not so much for its political statements as for its use of violence, which was considered graphic by the standards of the time. Battleship Potemkin’s premiere in December 1925 (the first time a film was ever shown in Moscow’s famed Opera and Ballet venue) was a great success. An invited audience of party officials and the veterans of the failed 1905 revolution during which the real Potemkin revolt took place broke into spontaneous applause throughout the film, particularly the classic moment when the Potemkin’s crew raised the red Communist flag (which was shot with a white flag and hand tinted on the print itself.) Eisenstein, his cinematographer Eduard Tisse, and his assistants all took the stage at the screening’s conclusion and received a thunderous ovation with one Moscow paper stating, “Everything is alive in the hands of these superb masters of the screen.”

After its premiere in the Soviet Union, Potemkin was shown in the United States with the help from actor Douglas Fairbanks who stated: “Battleship Potemkin was the most powerful and the most profound emotional experience in my life,” after attending the Berlin premiere with actress Mary Pickford. Unfortunately the popularity of the film inspired widespread demonstrations in the area where Eisenstein filmed the classic Odessa Steps sequence, which sparked off the arrival of the Potemkin in Odessa Harbour, and both The Times of London and the resident British Consul reported that troops fired on the crowds with accompanying loss of life (the actual number of casualties is unrecorded) as Roger Ebert writes, “That there was, in fact, no czarist massacre on the Odessa Steps scarcely diminishes the power of the scene … It is ironic that Eisenstein did it so well that today, the bloodshed on the Odessa steps is often referred to as if it really happened.”

The film’s potential to influence political violence through emotional response was noted by Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, who called Potemkin “a marvelous film without equal in the cinema … anyone who had no firm political conviction could become a Bolshevik after seeing the film.” The film was not banned in Nazi Germany, although Himmler issued a directive prohibiting SS members from attending screenings, as he deemed the movie inappropriate for the troops. German military and police officials fought to have the film banned prior to the films scheduled premiere in the German capital, as Wiemar Government feared that the film might create an ideological foothold for Bolshevism in Germany.

It was shown in an edited form in Germany, with some scenes of extreme violence edited out by its German distributors with the character of Vakulinchuk even changed and reworked to not be the tragic martyr he originally symbolized. A written introduction by Leon Trotsky was cut from Soviet prints after he ran foul of Joseph Stalin and the film was banned in West Germany and Britain until 1954; and was given an X-rated until 1978. The emotionally and artistic impact that Potemkin originally created unfortunately led to its destructive censorship, and of its alteration of Eisenstein’s original image as decades of re-cuts, re-translations and public domain versions have distorted its original power and intensity.

Sergei Eisenstein is looked at today as the “Father of Montage” and along with F.W. Murnau and D.W. Griffith, is considered one of the greatest and most important silent directors of all time. Eisenstein pioneered the Soviet Montage movement and his masterpiece Battleship Potemkin is looked at as the film in which he perfected his technique. Eisenstein’s feature film was a 1925 film titled Strike which depicts a strike in 1903 by the workers of a factory in pre-revolutionary Russia, and their subsequent suppression. The film is most famous for his Montage sequence near the end of the film in which the violent suppression of the strike is cross-cut with footage of cattle being slaughtered, (in which the idea is again used decades later in Frances Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now) as Eisenstein is known for using animals as political metaphors. Eisenstein later became renown for his historical sound epics Alexander Nevsky, and his two-part Ivan the Terrible which are now looked at as masterpieces of Russian cinema. Part 1 was released in 1944 but Part 2 was not released until 1958 due to political censorship. The films were originally planned as part of a trilogy, but unfortunately Eisenstein died before filming of the third part could be finished.

-Bruce Bennett

Like most Propaganda films, Eisenstein deliberately avoids creating any human three-dimensional character’s throughout the story of Battleship Potemkin. Vakulinchuk who probably has the most memorable character in the film is only used merely as a symbol, and is there purely to give the sailors motive for their uprising. Within Soviet Montage most character’s are made up of non-actors as a form of typage so they could simply represent archetypes instead of real three-dimensional characters, like for example: the sailor, the peasant, the mother, the nurse, the schoolgirl, the baby, the Tsarist, and the soldier. Most of the people of Odessa are seen less as individual people and more as a large mass that represents a political symbol. Causality and individual stories weren’t as important as large scale events that impacted large masses of men and women who moved in a form of unison. Even the dialogue is limited to simple expressions like anger and fear, and there is no personal human drama to counterbalance the larger political message of the story. Eisenstein felt that montage should proceed more from rhythm and of its linkage of shots, and less involve itself with the story and characters. Shots are purposely cut when they lead up to a certain point and don’t linger on because that would result in the audience to develop a personal interest in the story and to its individual characters. Since its release, Battleship Potemkin has often been cited as one of the finest propaganda films ever made and considered amongst the greatest films in the world. The film was named the greatest film of all time at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958 and similarly, in 1952. Sight & Sound magazine cited The Battleship Potemkin as the fourth greatest film of all time and has been voted within the top ten in the magazine’s five subsequent decennial polls, dropping to number 11 in the 2012 poll. It ranked #3 in Empire’s The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema in 2010 and in April of 2011, Battleship Potemkin was re-released in UK cinemas, distributed by the British Film Institute with Total Film magazine giving the film a five-star review, stating, “…nearly 90 years on, Eisenstein’s masterpiece is still guaranteed to get the pulse racing.” In 2004, Kino Lorber released a glorious restored DVD and blu ray of the film with many of the scenes of violence restored, as well as the original written introduction by Trotsky. The previous titles, which had toned down the mutinous sailors revolutionary rhetoric, were corrected so that they would now be an accurate translation of the original Russian titles in the film. The Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum fur Film und Fernsehen, commissioned a re-recording of the original Edmund Meisel score, performed by the Babelsberg Orchestra and conducted by Helmut Imig. (To retain its relevance as a propaganda film for each new generation, Eisenstein hoped the score would be rewritten every 20 years as the original score was composed by Edmund Meisel.) Battleship Potemkin’s fatal flaw as a film is a flaw that every film has that is made purely for propaganda purposes; The power of its message suffers and can looked upon by many as dated, when taken away from its original historical context. And yet with the right audience, the film can still be appreciated for its shocking and revolutionary images of violence and remarkable and groundbreaking achievements in editing and cinematography.