Battle of Algiers, The (1966)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Battle of Algiers Gillo Pontecorvo” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Isn’t it cowardly to use your women’s baskets to carry bombs, which have taken so many innocent lives?

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Battle of Algiers Gillo Pontecorvo” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]”Isn’t it cowardly to use your women’s baskets to carry bombs, which have taken so many innocent lives?

“Isn’t it even more cowardly to attack defenseless villages with napalm bombs that kill many thousands of times more? Obviously, planes would make things easier for us. Give us your bombers, sir, and you can have our baskets.”

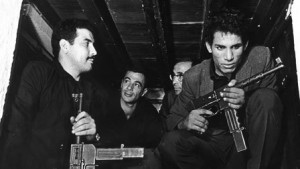

Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers is one of the most powerful political films about terrorism and guerrilla warfare and its political themes and ideologies are frighteningly still relevant in today’s universal headlines. The Battle of Algiers was a film that was made in 1965 but released in late 1967 as it tells the fights and emerging tactics in Algeria between the years of 1954 and 1962, where France tried and failed to contain a nationalist uprising, and as its methods were successful in Algeria they would later be adapted by the Cubans, the Palestinians, the Viet Cong, the IRA and South African militants, and the United States of America. For The Battle of Algiers, Gillo Pontecorvo and cinematographer Marcello Gatti took from the cinematic masters of Soviet Montage and Italian neorealism and experimented with various styles and techniques including shooting in stark black and white cinematography, casting non-actors in the roles of its Algerians, and shooting everything live and on location including Algiers and in the European quarters of Casbah; all which would help create an authentic look of newsreel and documentary like footage. When the film was released this effect convinced audiences into believing they were watching real life war footage and so Americans released a disclaimer for the film that said “Not one foot of newsreel was used.” In a film that was cast almost entirely with non-actors, Pontecorvo decided to use a Paris stage actor to play Col. Mathieu, a commander of the paratroopers sent in to back up the French police. Mathieu, himself a member of the French resistance to the Nazis, is calm, analytical, strategic in his thinking, and considers the FLN to be the enemy, not a malevolent force. Pontecorvo brilliantly cuts back and forth between Col. Mathieu and a raggedy band of FLN fighters, most importantly Ali la Pointe, a petty criminal who converted to the FLN after witnessing a beheading in prison. [fsbProduct product_id=’737′ size=’200′ align=’right’]And yet The Battle of Algiers is legendary in its explicit documentary-like detail of its iconography of police shootings, terrorist bombings, child martyrs, interrogation rooms, general strikes, torture chambers, security breaches, riot demonstrations, and violent reprisals, which supposedly adapted the film into a training manuel for the Black Panthers, Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front. Because of that The Battle of Algiers gained a reputation for inspiring political violence with France banning it for five years and Jimmy Breslin declaring on TV in 1968, “The Battle of Algiers is a training film for urban guerrillas.” Even today, The Battle of Algiers is still a cinematically important and crucial film, and as of recently in September 2003 the New York Times reported that the movie was being shown in the Pentagon to military and civilian experts, regarding it as a useful illustration of the problems faced in Iraq. One of the most unforgettable moments in the film is the sequence in which three Algerian women masquerading as upscale French women, plant bombs at various public hangouts in the French quarter. We then get vivid snapshots of teenagers dancing, men sipping drinks and a toddler licking his ice cream cone, all before its unenviable explosion. This disturbing act of terrorism followed by the powerful and unsentimental score by Ennio Morricone is still relatable to us all as it is a frightening and prophetic parallel to the bombings in Israel, the U.K., Iraq, and of the tragic 2001 September 11th attacks in the United States of America.

PLOT/NOTES

It first begins in 1957 in Alger as French officers finally get a FLN member to talk after hours of beatings and torture. “Couldn’t you have talked sooner? It would’ve gone easier for you.” says one of the paratroopers. The story begins and ends from the perspective of Ali la Pointe who is the last remaining FLN fighter who is surrounded by the French military in Casbah after one of his men reveals his location. It shows Ali and a group of people hiding within the walls of one of the apartment buildings keeping quite. “Maybe they don’t know were here…” whispers one of them. The French then announce,”Ali La Pointe, the house is surrounded. It’s useless. Listen good! You’re the last one. It’s all over. The organization’s finished. Everyone’s dead or in prison.”

It then flashes back 3 years earlier to Alger in 1954 where it portrays Ali as nothing but a petty criminal and while in prison for a small crime he watches a respected FLN fighter get executed outside the prison grounds but not before yelling to everyone in the prison “long live Algeria!!’ While in prison Ali is politically radicalized and 5 months later when out is recruited to the FLN. His first job in Casbah is handed to him by a boy named Petit Omar, a street FLN messenger who gives him a note to shoot a policeman who meets daily with an Algerian informer at a local café in Casbah. (Ali of course has Omar read the note since it seems he can’t read.) The note informs Ali that a woman will be standing outside a café, will hand him a gun and he is to then shoot the officer in the back.

Before shooting the officer Ali decides to make a huge scene by confronting him with the gun and saying before shooting, “So your afraid now! Look how the organization deals with traitors.” When he pulls the trigger he realizes it is not loaded. He luckily gets away and catches the woman who handed him the gun saying, “you bitch! You set me up!” They both run out of site from the police and she takes him to meet her contact who set this up.

The contact is El-hadi Jafar who is the leader of the FLN and Jafar says to him, “What if you were a traitor? We had to be sure. Say you’d been a police spy, the FLN contacts you in prison, you pretend to be for the cause, and the French let you escape. You escape, go to the address the FLN gives you in prison, and infiltrate us.”Jafar then tells Ali they told him to shoot the cop instead of the informer because if he was working for the French we wouldn’t have objected shooting a civilian but would have objected shooting a French police officer. Since Ali did pull the trigger, he has symbolically committed a murder which makes him earn their trust and entrance into the FLN. “We need to get organized, Jafar says, “and secure our hideouts. Then we can take action. The organization’s getting stronger, but there are still too many drunks, whores, junkies, people who talk too much, people ready to sell us out. We must win them over or eliminate them.”

Over time around April 1956 Jafar and Ali recruit several other members into the FLN which are mostly younger impressionable boys by telling them to join the FLN because “they our the future of cleaning up Casbah.” They have them intimidate people that they believe are traitors or a threat to their cause. There is a scene of a large group of kids attacking an adult and dragging him in the streets. Ali is in the town of Casbah trying to rid it of all drugs and crime and is looking for Hassan El-Blidi. When finally confronting him he tells him he is sentenced to death and shoots him down. He tells El-Blidi’s men, “Don’t try it! Take a good look. Things will change in the Casbah! We’ll clean this place up.”

When the French police get involved in Casbah with what the FLN is trying to do it starts a sudden war, especially when the French governor puts Algiers under tight police control, by closing off streets. There is a disturbing montage of planned out assassinations of French officers by the FLN which usually involves two people: one to place the weapon in a hidden area and another to walk up and take it at a certain time and shoot the enemy. There is a scene where a boy is following a French soldier from behind and because of looking suspicious is stopped by the officer. “What are you up to?” The boy just says, “I’m meeting friends at the beach and this is my route.” The French officer tells him to beat it and right when the boy reaches the location of the hidden gun in a street garbage can, he takes the gun out and shoots the officer in the back.

While the kid takes off French police are driving down the streets looking for the shooter and people are standing outside their homes watching the hysteria. The people start pointing fingers at a homeless man in the streets and automatically believe he is the suspect yelling, “Filthy Arab! Stop him!” Because of all these French shootings the French start setting up roadblocks and checkpoints between the Casbah and the European quarter, which lead to French officers checking everyone’s ID’s at each checkpoint before they can let civilians go through.

There are two very powerful scenes of both sides committing horrible atrocities to not only their enemies but to innocent civilians and women and children who are unfortunately caught in the middle. One powerful scene is a high-class Frenchman leaving a social gathering with another and they both drive down and get through the Casbah security roadblock by of course showing their government I’D’s. While in the inner city of Casbah outside of civilian homes he and his partner get out of the car and set a bomb near one of the civilian buildings and take off. The bomb explodes and there is a horrific scene with a haunting score by Ennio Morricone which becomes mournful as survivors pick through the debris and the wreckage showing the several women and children who were killed during the blast.

Now angering the FLN because of the horrifying acts of the French, Ali and a group of FLN members want to confront the French officers with guns chanting, “murderers!!!” Before confronting the French Ali is told by Omar that Jaffar wants him to not confront the French officers this way because they will get slaughtered and to get their revenge a different way. Ali yells “Halt!” Jafar comes out and yells, “Stay calm! The FLN will avenge you!”

The second powerful scene, and probably the most memorable scene of the film shows three Algierian woman cutting their hair, dyeing their hair color, applying make-up and wearing fancy dresses to look as close as they can as upscale loose-living French women. When Jafar walks in and observes these women one doesn’t look very convincing to get through the French roadblock. “I’ll use my son,” she says. “It will work.” Jafar says “Okay, but use the rue du Divan checkpoint. It’s easier there.” He then tells the three of them, “Good luck.” They each get handed handbags with timed bombs inside, and have only 30 minutes to place them in there specific locations. While getting pass the checkpoint’s which include several French security, two of the younger more attractive women flirt their way with the French officers to be let through while the older one uses her son which makes her look less threatening.

Pontecorvo shoots the tension simultaneously as all three woman go to the three public places in the French quarters and casually put down their handbag baskets knowing they have only 30 minutes to do so and leave. One of the women as she walks into a dance club is offered a seat by a man at the bar and when sitting she casually places her handbag on the floor and uses her feet to push it under another person’s chair while looking up at the clock. One striking shot is all the Algier women slowly observing all the victims before leaving their locations. The one in the night club watches all the young French teenagers happily dancing to music, sipping on drinks and while the other woman in the café observes a innocent little boy eating an ice-cream. Once the first explosion occurs in the café the people in the dance club hear it and go out and see what the sound was. The people think a propane tank must have exploded, think nothing of it and go back into the bar to continue dancing. Suddenly the bomb in the dance club goes off, and the haunting score by Ennio Morricone occurs once again as you see the wreckage and deaths of all the victims in the dance club. While the injured are carrying the body’s out of the wreckage you then hear the third bomb go off off-screen.

Eventually because of these horrific terrorist attacks, in January 1957 the French government gets involved and Col. Mathieu, commander of paratroopers is sent in to back up the police, as they arrive with the French happily welcoming them. One great speech he tells his men about the enemy they are fighting is something the American military leaders probably told their troops when fighting in Afghanistan:

“We have an average of 4.2 attacks a day. We have 400,000 Arabs in Algiers. Are they all are enemies? We know their not. It’s a faceless enemy unrecognizable, blending in with hundreds of others. It is everywhere. In cafes, in the alleys of the Casbah, or in the very streets of the European quarter. Among all these Arab men and women are the perpetrators. But who are they? How can we recognize them? ID checks are ludicrous if anyone’s papers are in order, it’s the terrorists. We have to start from scratch. The only information we have concerns the organization’s structure. Let’s start from there. It’s a pyramid organization made up of a series of sections. These sections, in turn, are made up of triangles. No.1 finds two others: No 2. and no. 3. This makes up the first triangle. Now no. 2 and no. 3 each select two men: 4, 5, 6, 7. The reason for these geometrics is that each organization member knows only three other members: The one who chose him and the two he himself chose. Contact is made only in writing. That’s why we don’t know are adversaries, because in point of fact, they don’t know each other. To know them is to eliminate them.”

After two years of fighting the United Nations will now openly debate on the Algerian question and because of that the FLN is calling a week-long strike. Col. Mathieu has a close eye on the FLN and does believe the people will listen and go on strike.

Jafar arrives at Ali’s apartment and Ali shows him a hole he made inside the wall of his place to hide if the apartment is searched by French police. Jafar orders Ali to take Si Ben M’Hidi a respected FLN leader to the mosque. When alone M’Hidi asks Ali what he thinks of the strike. Ali believes it will work but the French will try everything to break it. M’Hidi says, “they’ll do more than that, because we’ve given them an opportunity. Every strike will be a recognizable enemy. The French will take the offensive. Jafar says you weren’t in favor of the strike.” Ali says, “No, I wasn’t. Because we were ordered not to use arms.” M’Hidi says, “Acts of violence don’t win wars. Neither wars nor revolutions. Terrorism is useful as a start. But then, the people themselves must act. That’s the rationale behind the strike. To mobilize all Algerians to gather our strength. It’s hard enough to start a revolution…even harder to sustain it…and hardest of all to win it. But it’s only afterwards once we’ve won, that the real difficulties begin.”

The French suddenly one morning come through the houses of the people of Casbah knocking down doors and pulling people out yelling, “You bastards! We’ll tell you to strike!” The French soldiers bully the civilians and the ones who aren’t working are believed to be working for the FLN. When the media gets ahold of Col. Mathieu and they question his sudden ruthless strategies while Col. Matheu informs them hes assessing the situation. One of the reporters tells him the strike the Algerians were doing seemed successful and might convince the UN. Col. Mathieu says the U.N is too far away to care. One reporter asks Col. Mathieu if he likes Sartre. He says, “No, but I like him even less as a foe.”

Over the next few days following the continuing strike the French are telling the people in Casbah that the FLN are condemning them from poverty work and the closing of their businesses speaking to them through a microphone; to get the people to talk and reveal the identities of the FLN. A young boy grabs the microphone while the French aren’t near it and speaks to the people of Casbah saying, “Algerians! Brothers! Take heart! The FLN tells you not to be afraid! Don’t worry! Were winning! The FLN is on your side!” In the final day of the strike the French officers are tearing down businesses and beating civilians of Casbah to get them to break and speak up. Col. Mathieu tells his troops the end of the strike means nothing and to keep at it in Casbah. He then gives one of the best speeches of the film saying to his men: “Any of you ever suffer from tapeworm? It’s a worm that can grow infinitely. You can destroy its thousands of segments but as long as the head remains it rebuilds and proliferates. The FLN is similarly organized. The head is the Executive Bureau. Several persons. As long as they’re not eliminated, we’re back to zero.”

He then shows the four main heads of the group which are Si Murad, Ramel, Jafar and Ali la Pointe. Some French soldiers come to Ali’s place and ask for him as the three main leaders hide in his hole in the wall he built. They then hear the paratroopers announcing lies to the people in Casbah informing them that Si Murad, Ramel, Jafar and Ali were caught and killed; to make the people come out and speak. Jafar decides to have the four of them split up in different hideouts and reestablish their contacts. They escape by disguising themselves as women but when caught by a few French guards they quickly shoot them down and run off as Jafar and Ali are helped by a neighbor who lets them hide in her well. Eventually M’ Hidi was caught and arrested and after a bombing that occurs at a large French sporting event a French journalist asks Ben M’ Hidi:

“Mr. Ben M’ Hidi, isn’t it cowardly to use your women’s baskets to carry bombs, which have taken so many innocent lives?

“Isn’t it even more cowardly to attack defenseless villages with napalm bombs that kill many thousands of times more? Obviously, planes would make things easier for us. Give us your bombers, sir, and you can have our baskets.”

Weeks later M’Hidi hangs himself in his cell as the reporter’s question Col. Mathieu on his way of torture to make his prisoners talk. Col. Mathieu says, “The word ‘torture’ isn’t used in our orders. What form of questioning must we adopt? Civil law procedures which take months for a mere misdemeanor? No gentlemen, believe me. It’s a vicious circle.” In a disturbing montage you then see Col. Mathieu’s men use tactics that resort to discriminating and intimidating the Algier civilians to have them talk out of fear. The methods the French use to interrogate and get answers from them are hideous tortures including torches and electroshock equipment that also have been used by the Palestinians, the Nazi Gestapo, Fidel Castro, the Viet Cong, the IRA and South African military. These gruesome tactics are used to release information and have the Algiers betray the names of their co conspirators which eventually leads to many arrests of the FLN.

This off course gets worse for the French with the FLN fighting back when they start doing drive by shootings on French civilians; in which leads to a fatal accident. Eventually the French catch and arrest Ramel and now surround Si Murad’s hideout. Col. Mathieu announces if Si Murad gives himself up he won’t be harmed as long as he brings down his guns first. Si Murad instead takes a bomb and sets it to go off in thirty seconds and places that in a basket which is being lowered down towards the French troops; with them believing it to be his guns. When the bomb goes off it kills several of Col Mathieu’s men including Si Murad.

This off course gets worse for the French with the FLN fighting back when they start doing drive by shootings on French civilians; in which leads to a fatal accident. Eventually the French catch and arrest Ramel and now surround Si Murad’s hideout. Col. Mathieu announces if Si Murad gives himself up he won’t be harmed as long as he brings down his guns first. Si Murad instead takes a bomb and sets it to go off in thirty seconds and places that in a basket which is being lowered down towards the French troops; with them believing it to be his guns. When the bomb goes off it kills several of Col Mathieu’s men including Si Murad.

The next scene is Col. Mathieu and his troops now surrounding Jafar’s hideout. Jafar is ordered to come out or they will blow up the building. Eventually Jafar decides to give himself up right before they blow down the building; which is ironic since he as the leader won’t give up his life for his cause, but all of the followers that joined him gladly did. When arrested Col. Mathieu says to Jafar on his way to prison, “I’d have hated to blow you all up. Your picture and your file have been on my desk for months. I have the feeling I know you a bit.”

The climax of the film is where the film first opened; with Ali who is now the last member of the FLN hiding in the wall of his apartment with several others; while Co. Mathieu and his men evacuate his place. Knowing he and several others are hiding within the wall Col. Mathieu tells him to let the others out, or they will all be blown up. “You have another 30 seconds. What are you hoping for?” Yells Col. Mathieu. Of course Ali and the others don’t budge as everyone in Casbah are watching and waiting for the French to blow up the apartment. When the bomb is set everyone stands back as Ali and the others get killed in the blast; with the civilians crying watching from their homes. “The tapeworms headless now,” says one of Col. Mathieu’s men. “Yes, we’ll hear no more of it…for the time being.”

The last shot of the film shows the Algerians fighting back again two years later; with thousands protesting in the street with flags. After several riots and murders the Algerians finally win their independence from the French on July 2nd 1962.

ANALYZE

Legend has it that an American moneyman agreed to finance Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 neorealist classic Bicycle Thieves with one stipulation—that the role of the common laborer whose meager capital is stolen be played by Cary Grant. Apocryphal or not, that stroke of casting would have utterly—even chemically—transformed the film. De Sica chose instead to hire a metalworker off the street, because anonymity was of the very essence in describing a world where ordinary people are casually ground down by a machinery beyond their knowledge or control. An equally aberrant proposal sowed the seed for one of the great incendiary epics in film history, Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 The Battle of Algiers. The director and his coscreenwriter, Franco Solinas, wanted to commemorate the popular uprising that had succeeded in ousting the French from Algeria in July 1962. That event triggered a seismic wave of anticolonial movements across the Third World, serving both as a millennial image of freedom and a more practical lesson in the violent means deemed necessary to win it. The Battle of Algiers would itself help to galvanize those struggles by uniting the revolutionary prerequisites of a cool head and a blazing heart. No other political movie of the past fifty years bears the same power to lift you from your seat with the incandescent fervor of its commitment. And none before or since has anchored that passion in so lucid a diagnosis of the fault lines separating exploiter and exploited. Pontecorvo’s work can now be recognized as an absolute pinnacle of countercinema—the ne plus ultra of a mode that seeks to intervene strategically in the war for social change. Still, the filmmakers initially developed their project with Paul Newman in mind.

He would portray a handsome bon vivant, once a paratrooper in Indochina, now a magazine reporter assigned to cover France’s latest imperial adventure in the Casbah. We can purely speculate on the rest—how our hero’s journalistic sangfroid might have crumbled before the worst Gaullist outrages, his vanity and complacency challenged by self-scrutiny, doubt, and progressive awareness of guilt. Then he would, perhaps, have experienced the birth of consciousness and a final, ardent dedication to the rebel cause. Whether Pontecorvo and Solinas held these or other cards up their sleeves, the resulting movie would almost certainly have been a compromise. You can understand the logic. A “difficult” subject demands the warranty of a box-office name to pacify backers and entice a wide audience, who will hopefully learn a thing or two. But the fact remains that Parà (the title of Solinas’s original treatment) is a story about Newman’s inner turmoil and only secondarily relates the far more ponderable misery of the Algerian people. That was the trenchant critique posed by Salah Baazi, a representative of the exiled Front de Libération Nationale, when he arrived in Italy to discuss the script. FLN military chief Saadi Yacef had envisaged his own revolutionary epic and, with Baazi, was now shopping around for a suitable director. The Italian collaborators had sidelined the independence movement in dramatizing its impact on a single European (to be played by an American). Baazi submitted an alternative script, written by Yacef, which Pontecorvo rejected in turn as “sickeningly propagandistic.” Clearly, a new approach was needed that would avoid the reciprocal snares of well-meaning foreign patronage and indigenous saber rattling—bring the anger and grim resolve of the combatants viscerally close but preserve a critical distance. In short, a creative synergy between First and Third Worlds.

Pontecorvo and Solinas laid the foundation with meticulous spadework, traveling to Algiers and Paris, interviewing eyewitnesses, compiling dossiers, studying and pondering. In due course, a game plan started to emerge. They wouldn’t repeat their previous mistake of individualizing the conflict as a speedway to emotional involvement. Psychology was a red herring. The Algerians had, after all, waged a political campaign in response to a collective experience of injustice. The revised film would chronicle nothing less than the battle of an entire nation for selfhood, though putatively by focusing on the FLN—the muscle and brains of the resistance. The problem was how to outflank normal viewing habits and solicit identification with a group hero; luckily, there were precedents. Among the 1920s Soviet masters, Vsevolod Pudovkin and, especially, Sergei Eisenstein had torpedoed the revolutionary proletariat across the screen into dialectical collision with Cossacks, kulaks, and fat-cat bourgeoisie. It was sensational agitprop melodrama, the contending factions typed as monumental cartoons of nobility and depravity, the propulsive editing rhythms allowing the audience scant opportunity to think or even breathe. “Smashing skulls with kino fists” was the way Eisenstein picturesquely put it. If that policy seemed excessively strong-armed, there was the homegrown tradition of neorealism—in particular, Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946, the film that emboldened Pontecorvo to pick up a camera in the first place). Restaging the Italian liberation and its aftermath with the stark immediacy of a newsreel, Rossellini fostered the careful illusion that events were unfolding voluntarily, their horror, beauty, and ulterior significance waiting to be seized.

Pontecorvo and Solinas knew that every artistic decision is simultaneously an ethical one. Though as Westerners, and fellow-traveling Marxists, they hoped to forge solidarity with the Algerian underclass and honor the integrity of its suffering. Neither motive would be best served by a glossy professionalism that effectively pulled rank on the victims—or worse, reduced them to mouthwatering local color. Again, neorealism, with its democratic ideal (often finessed in practice) of placing nonactors in their vernacular setting, was the indispensable compass. Pontecorvo recruited his amateurs (almost one hundred and fifty of them, including Saadi Yacef as El-hadi Jaffar, a thinly fictionalized version of himself) more for their physical verisimilitude than their innate ability. He admitted one exception: stage veteran Jean Martin, whose dry, punctilious performance as the French military chief Colonel Mathieu sheds irony over the whole imperialist enterprise. But the Italian school hadn’t always shunned cheap pathos, and further austerity was called for. The filmmakers found it in a genre long associated with seriousness, social engagement, and plain truth—documentary. The Battle of Algiers would emulate the on-the-hoof aesthetic of 1960s cinema verité. Pontecorvo duly flung himself into the breach with a handheld camera that wobbled, zoomed, and reframed as though excitedly clawing at the action. What matter if the riots and atrocities were minutely orchestrated or if Marcello Gatti’s grainy, high-contrast cinematography was synthesized with negative dupes? Pontecorvo also knew that realism can’t be achieved without artifice.

But documentary in itself wasn’t enough. Raw actuality (or its cunning double) functions as an abrasive in the movie, scrubbing away any tendency toward spurious glamour and romanticism. All the same, The Battle of Algiers was conceived as the saga of a proud citizenry throwing off its chains, so that romanticism must be made to creep quietly, almost subliminally, back in. Ennio Morricone’s score isn’t the symphonic flattening of your tympanum by which Hollywood dependably celebrates momentous occasions. Its themes, percussive and elegiac, appear sparingly, but with a ritual inevitability that suggests hidden, antithetical forces sweeping the characters along. The blunt yet measured editing; the concatenated procession of episodes relentlessly ticking down; the repeated shots of a community waiting or mourning, seen from high above; the leitmotif of the Muslim women’s dreadful war whoops, echoing over the Casbah—all contribute to the impression of flowing like a vast, unstoppable tide.

That tide is history, of course. The main part of the narrative treats the escalating tactics—police shootings, terrorist bombings, a general strike—that the FLN deployed against the French from 1954 until the movement’s (temporary) defeat in 1957. The details are so explicit that The Battle of Algiers was adapted into a training manual by the Black Panthers and the IRA—even screened (for a more cautionary purpose, one assumes) at the Pentagon. Pontecorvo and Solinas observe the endless chain of actions and reprisals like scientists confirming the invariability of some natural law. The strict formal symmetry of assassinations, bombs, and vengeful mobs on either side has led liberal-minded critics to the comfortable opinion that the movie is balanced—essentially declaring a pox on both houses. But the objectivity belongs to history alone, weaving its secret design, indifferently crushing its pawns, ever rolling on. As for the filmmakers, they view colonialism as an unmitigated evil and join hands with the weak against the strong. In the sole sequence expressing a degree of ambivalence, the FLN announces a purity crusade to rid the district of counterrevolutionary riffraff. Later, we watch aghast as Muslim street children swarm around a harmless drunk, then drag him down the stairs to who knows what nightmarish fate. That may be an example of sectarian “fanaticism,” but it’s also undeniable that the Algerians require dignity and discipline to advance their fight. Otherwise, Pontecorvo stands firm in the insurgent camp and aims to bring the viewer over. In most earlier films about colonialism, the natives were depicted as aloof, menacing, treacherous, if sometimes ravishingly exotic. Pontecorvo’s natives retain these attributes, but the director cleverly reverses their intention. Here, it’s the French who appear remote—pale, anemic, and corporate in their army fatigues or police uniforms. Apart from the sardonic Colonel Mathieu, they’re denied the least spark of personality and systematically refused close-ups. The Algerians, by contrast, are given flesh, sensuality, bodies, and, above all, faces. Pontecorvo doesn’t press the point with brutal caricature, in the manner of Eisenstein. The Europeans are shown as just doing their jobs, while the “poetry” of the Africans is glimpsed in passing, never italicized.

No doubt we are aligned the more surely with the seditionists by the unconscious nature of the appeal. The acid test of this comes in the unforgettable sequence where three Algerian women plant bombs at various crowded hangouts in the French quarter. Masquerading as loose-living Europeans, carrying mortality in a shopping basket, they would be sinister femmes fatales in another context. But we have been made to collude with their perspective and look through their eyes at the innocents about to be slaughtered. For once, the French settlers are particularized—in vivid snapshots of teenagers dancing, men sipping drinks and idly chattering, a toddler licking an ice cream cone. The women take no pleasure in their mission and shoulder full responsibility for its appalling consequences. But history has spoken. If we can accept the grievous necessity of these deaths, then we consent to everything. Pontecorvo has penetrated our Western self-absorption and let in the harsh light of reality. If not, the movie at any rate offers iconography—checkpoints, child martyrs, interrogation rooms, torture chambers—that has become timely again and worth meditating on. “It is the moment of the boomerang,” Jean-Paul Sartre wrote of the Third World rebellions in his introduction to Frantz Fanon’s 1961 The Wretched of the Earth (a book that Pontecorvo and Solinas read avidly). The Battle of Algiers offers an indelible image of how that boomerang pitilessly returns, which we ignore at our peril.

For Fanon, violence is endemic to colonial rule, tightening its grip over decades and centuries, finally leaving no option save bloody payment in kind. Pontecorvo follows this intransigent thesis to the letter, and few artists have risked their necks so forthrightly. That may explain why a movie universally acknowledged as a radical touchstone has spawned only a tiny handful of imitators. Perhaps the most immediate beneficiary was Constantin Costa-Gavras, whose 1969 Z and 1973 State of Siege (cowritten by Solinas) investigate the paranoid mechanisms through which nominally legal governments snuff out subversion, real or fantasized. While the Greek director borrowed freely from Pontecorvo’s quasidocumentary technique, he siphoned it off into the accessible mold of conspiracy thrillers merely trimmed with dissident ideas. The rebranding of militancy as nail-biting entertainment spelled the beginning of the end for political cinema. In recent times, the pugilistic Oliver Stone has built a durable career on attacking icons and institutions with a sledgehammer. Briton Ken Loach continues to hoist the red flag in works (such as 1995’s Land and Freedom) that combine emotional intensity and hard-nosed materialist rigor. But the true heirs of The Battle of Algiers have been numberless filmmakers from Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, Senegal, Mali, Tunisia, Morocco, Palestine, and Algeria itself—inspired by Pontecorvo’s supreme empathy to tell their own stories of nationalist striving. Still, history moves on, and world cinema reflects market forces in an increasingly smooth, prettified style. The hour is more than ripe for The Battle of Algiers to renew its fire.

-Peter Matthews

For The Battle of Algiers, Pontecorvo and cinematographer Marcello Gatti filmed in black and white and experimented with various techniques to give the film the look of newsreel and documentary film. The effect was convincing enough that American releases carried a disclaimer that “not one foot” of newsreel was used. Although The Battle of Algiers is considered to be realistic in style, one might consider the film to not completely follow traditional documentary aesthetics. The film is quite heavily processed in some sequences, with image contrast being brought up for key dramatic moments, such as assassination sequences. The film is also mostly shot with a locked-off camera, meaning no dolly movements or complicated set-ups, but also no hand-held shots which would be more typical for the appearance of a modern documentary.

Pontecorvo chose to cast from non-professional Algerians he met, picking them mainly on appearance and emotional effect (as a consequence, many of their lines were dubbed). The sole professional actor of the movie was Jean Martin who played Col. Mathieu; Martin was a French actor who had worked primarily in theatre. Pontecorvo wanted a professional actor, but one with whom audiences wouldn’t be too familiar, which could have interfered with the movie’s intended realism. Martin had been dismissed several years earlier from the Théâtre National Populaire for signing the manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian War. Martin had also served in a paratroop regiment during the Indochina War as well as the French Resistance thus giving his character an autobiographical element. The working relationship between Martin and Pontecorvo was not always easy, as the director, unsure that Martin’s professional acting style wouldn’t contrast too much with that of the non-professionals, kept arguing with his acting choices.

Both music and effects performs as important functions for the movie. Indigenous Algerian drumming, rather than dialogue, is heard during a scene in which female FLN militants prepare for a bombing. In addition, Pontecorvo used the sounds of gunfire, helicopters and truck engines to symbolize the French methods of battle, while bomb blasts, ululation, wailing and chanting symbolize the Algerian methods. Gillo Pontecorvo had written the music for The Battle of Algiers, but because he was classed as a “melodist-composer” in Italy, it required him to work with another composer which was undertaken by his good friend Ennio Morricone

In 2003, the film again made the news after the Directorate for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict offered a screening of the film at The Pentagon in Washington D. C. on August 27, regarding it as a useful illustration of the problems faced in Iraq. A flyer for the screening read: “How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas. Children shoot soldiers at point-blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically. To understand why, come to a rare showing of this film.” Times reporter Michael Kaufman wrote that Pentagon audiences were “urged to consider and discuss the implicit issues at the core of the film, the problematic but alluring efficacy of brutal and repressive means in fighting clandestine terrorists in places like Algeria and Iraq.”

-Wikipedia

Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers was released in 1967 which was the peak of anti-war sentiment in the United States, and had a surprising box-office success for which it played for 14 weeks in Chicago. It was described at the time as impartial, between the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) and the French police and paratroopers both assigned to destroy it. The film’s essential fair-mindedness between both sides is perhaps its most striking and skillful feature as The Battle of Algiers when on to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and became nominated for three Academy Awards (in non-consecutive years) including Best Screenplay and Best Director in 1969 and Best Foreign Language Film in 1967. I believe Pontecorvo’s sympathies were slightly towards the FLN, and its answer relies on his choices when using Ennio Morricone’s powerful score. When the resistance is openly shooting down French police officers, or bombing police strongholds Pontecorvo’s chooses to withhold any use of Ennio Morricone’s score. And yet when the French police respond by killing the home of a terrorist, by blowing it up, the score becomes mournful as you tragically watch survivors picking up bodies through the debris. Even though Pontecorvo seems to have sided with the FLN, he portrays Col. Mathieu in a fair light. Col. Mathieu is a respectable man who was a member of the French resistance to the Nazis, and a veteran of the French defeat in Indochina who knows a lot of about dealing with urban warfare. He is calm, analytical, strategic in his thinking, and considers the FLN to be the enemy, not a malevolent force. Interestingly enough, in a film that has all non-actors, Pontecorvo decided to use a Paris stage actor for the character of Col. Mathieu. In 2010, the film was ranked #6 in Empire magazines The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema. The Battle of Algiers is one of the greatest political films ever alongside Costa Gavras’s 1969 French masterpiece Z. What is quite striking about this film is that it tries to portray both sides of the war in near equal light with the French and FLN committing horrendous atrocities of murder and yet portraying both their reasons for committing them. After we finally pulled our troops out of Iraq it was said during our 8 years there it cost billions of dollars and many thousands of lives. In August 2010, when the last US combat troops left, 4,421 had been killed and almost 32,000 had been wounded in action. The Iraqi casualty figure is hard to determine but is said to be around 109,032 deaths including 66,081 civilian deaths. What can a film like The Battle of Algiers today bring to the modern audience? I believe like all forms of art it depends on the person and what they personally would want to take away from it. Pontecorvo perfected in portraying the inner realities of guerrilla war-making so effectively, which is why their have spawned so many imitators throughout the years. In recent times it has been Oliver Stone who is highly known for attacking political themes and ideologies but the true heirs of The Battle of Algiers are the filmmakers all over the world. Still, history moves on, and world cinema continues.