Andrei Rublev (1966)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Andrei Rublev Andrei Tarkovsky” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]The great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the most difficult directors to grasp. A lot of people proclaim his films are too slow, too long and need extensive trimming in several scenes. But I believe his films which include long philosophical and existential dialogue and extensive and sinuous tracking shots, have audiences slow down, relax, and enter his world of complete meditation. When he allows a sequence to continue for what seems like an unreasonable length, he gives audiences a choice: We can either be restless and bored or we can give our mind a time to consolidate what we’ve just seen, what we’ve just heard, and what we’ve just witnessed. It gives us a chance to process our thoughts and feelings in terms of our own reflections. Many viewers who aren’t used to the works of Ingmar Bergman, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Robert Bresson or Yasujiro Ozu and are going into a Andrei Tarkovsky film wouldn’t stand a chance of sitting through it. Tarkovsky had a profound undercurrent of spirituality and consciously embodied the idea of a Great Filmmaker, making works that were uncompromisingly serious and ambitious, with no regard whatever for the audience, what the audience wanted or box office records. Andrei Tarkovsky is considered the greatest director to have emerged from Russia since the great director Sergei Eisenstein, and the reason that his films are not as widely known is because they are the most abstract, exhaustive, metaphysical, and intellectual, films that stem closest to the literary definition of art. All throughout his film-making career, Tarkovsky, having to deal with the constant struggles with the conservative Soviet regime, could make only a handful of movies, each of which can serve to be a live thesis on spiritualism and theology, all the while mastering the use of time and space, expressing what many would think would be inexpressible in the cinema. Andrei Rublev was considered the most historically audacious and controversial production in the twenty-odd years since Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and even though it was only Tarkovsky’s second feature, it is looked at as being his greatest achievement, and one of the greatest art films about the life of an artist ever made. [fsbProduct product_id=’732′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Andrei Rublev which Tarkovsky called a “film of the earth,” is set against the background of 14th century Russia, as the film is only loosely based on the life of the great icon painter, and seeks to depict a bleak and violent portrait of medieval Russia. Tarkovsky wanted to create a film that shows the artist as a world-historic figure, as its story is about the essence of art and the importance of faith, showing an artist who tries to find the appropriate response to the tragedies of his time. Too experimental, too frightening, too gory, and too politically complicated, it was not allowed to be released domestically in the officially atheist and authoritarian Soviet Union for years after it was completed, except for a single screening in Moscow. The film projects a sense of an entire world, a harsh and brutal force trying to assault ones senses while one views the naturalistic images Tarkovsky puts on the screen, including the composition of a cat walking across a corpse-filled church, wild geese fluttered over a savaged city, the slow decomposition of a ravaged swan, and a horse’s hooves on the surface of a turbid river (To Tarkovsky horses were a symbol for life). The films brutal depiction of violence, torture and cruelty toward animals, quickly gained controversy and gotten Tarkovsky into trouble with Soviet authorities, almost driving him into exile. Most of these disturbing sequences take place during the violent Tatar raid of Vladimir, showing for example such shocking images of a cow being set on fire and the stabbing death of a horse.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Andrei Rublev Andrei Tarkovsky” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]The great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the most difficult directors to grasp. A lot of people proclaim his films are too slow, too long and need extensive trimming in several scenes. But I believe his films which include long philosophical and existential dialogue and extensive and sinuous tracking shots, have audiences slow down, relax, and enter his world of complete meditation. When he allows a sequence to continue for what seems like an unreasonable length, he gives audiences a choice: We can either be restless and bored or we can give our mind a time to consolidate what we’ve just seen, what we’ve just heard, and what we’ve just witnessed. It gives us a chance to process our thoughts and feelings in terms of our own reflections. Many viewers who aren’t used to the works of Ingmar Bergman, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Robert Bresson or Yasujiro Ozu and are going into a Andrei Tarkovsky film wouldn’t stand a chance of sitting through it. Tarkovsky had a profound undercurrent of spirituality and consciously embodied the idea of a Great Filmmaker, making works that were uncompromisingly serious and ambitious, with no regard whatever for the audience, what the audience wanted or box office records. Andrei Tarkovsky is considered the greatest director to have emerged from Russia since the great director Sergei Eisenstein, and the reason that his films are not as widely known is because they are the most abstract, exhaustive, metaphysical, and intellectual, films that stem closest to the literary definition of art. All throughout his film-making career, Tarkovsky, having to deal with the constant struggles with the conservative Soviet regime, could make only a handful of movies, each of which can serve to be a live thesis on spiritualism and theology, all the while mastering the use of time and space, expressing what many would think would be inexpressible in the cinema. Andrei Rublev was considered the most historically audacious and controversial production in the twenty-odd years since Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and even though it was only Tarkovsky’s second feature, it is looked at as being his greatest achievement, and one of the greatest art films about the life of an artist ever made. [fsbProduct product_id=’732′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Andrei Rublev which Tarkovsky called a “film of the earth,” is set against the background of 14th century Russia, as the film is only loosely based on the life of the great icon painter, and seeks to depict a bleak and violent portrait of medieval Russia. Tarkovsky wanted to create a film that shows the artist as a world-historic figure, as its story is about the essence of art and the importance of faith, showing an artist who tries to find the appropriate response to the tragedies of his time. Too experimental, too frightening, too gory, and too politically complicated, it was not allowed to be released domestically in the officially atheist and authoritarian Soviet Union for years after it was completed, except for a single screening in Moscow. The film projects a sense of an entire world, a harsh and brutal force trying to assault ones senses while one views the naturalistic images Tarkovsky puts on the screen, including the composition of a cat walking across a corpse-filled church, wild geese fluttered over a savaged city, the slow decomposition of a ravaged swan, and a horse’s hooves on the surface of a turbid river (To Tarkovsky horses were a symbol for life). The films brutal depiction of violence, torture and cruelty toward animals, quickly gained controversy and gotten Tarkovsky into trouble with Soviet authorities, almost driving him into exile. Most of these disturbing sequences take place during the violent Tatar raid of Vladimir, showing for example such shocking images of a cow being set on fire and the stabbing death of a horse.

PLOT/NOTES

Prologue:

The film’s opening shows the preparations for a hot air balloon ride. The balloon takes off from the roof of a church, with a man named Yefim roped beneath the balloon, at the very moment of arrival of an ignorant mob trying to thwart the flight. The man is highly delighted by the sight from the air, entranced by the beautiful flight of being above the world, but can not prevent a crash landing. Yefim is the first of several creative characters, representing the daring escapist, whose hopes are easily crushed. After the crash, a horse is seen lolling by a pond in slow motion, a symbol of life — one of many horses in the movie.

The Jester, Summer 1400:

Andrei (Anatoli Solonitsyn), Danil and Kirill are wandering monks, looking for work. The three represent different creative characters. Andrei is the observer, a humanistic artist who searches for the good in people and wants to inspire and not frighten. Danil is withdrawn and resigned, and not as bent on creativity as on self-realization. Kirill lacks talent, yet strives to achieve prominence. He is jealous, self-righteous, very intelligent and perceptive. The three have just left the Andronikov Monastery, where they have lived many years, heading to Moscow. When leaving Danil says, “I passed this birch every day and never noticed it. When you know you’ll never see it again, it means something.”

During a heavy rain they seek shelter in a barn, where a group of villagers are being entertained by a jester. The jester, or skomorokh, is a bitterly sarcastic enemy of the state and the Church, who is earning a living with his scathing and obscene social commentary and by making fun of the Boyars. He ridicules the monks as they come in, and after some time Kirill leaves unnoticed. “God sent priests but the Devil sent Jesters,” says Danil. Shortly after, the skomorokh is picked up by a group of soldiers, who knock him out headfirst against a tree and take him away while the soldiers destroy his musical instruments.

Theophanes the Greek, Summer-Winter-Spring-Summer 1405–1406:

Kirill arrives at the Theophanes the Greek’s workshop, where Theophanes the Greek, a prominent and well-recognized master, is working on another of his icons. Theophanes the Greek is portrayed as a complex character: an established artist even better than Andrei, humanistic and God-fearing in his views yet somewhat cynical, regarding his art more as a craft and a chore in his disillusion with other people. His young apprentices have all run away to the town square, where a convicted criminal is about to be tortured and executed in public. Kirill talks to Theophanes, and the artist, impressed by his erudition, invites him to work as an apprentice on the decoration of Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow. Kirill refuses at first, because of self-doubt. “In these paintings there is simplicity without gaudiness.” Theophanes says, “I see you are wise.” Kirill responds, “if one is ignorant they are better to be guided by ones heart.” Theophanes says, “In much wisdom there is much grief and he who increases knowledge increases sorrow.”

Eventually Kirill accepts his offer on the only condition that Theophanes will personally come to the Andronikov Monastery and invite Kirill to work with him in view of all the fraternity and especially in front of Andrei Rublev. The three monks are back at the Andronikov Monastery. Theophanes the Greek sends a messenger to Andrei to ask him for his assistance in decorating Cathedral of the Annunciation. Both Danil and Kirill are agitated by the recognition Andrei experiences. Danil refuses to accompany Andrei and reproaches him for accepting Theophanes’s offer without considering his fellows, but soon repents of his temper and wishes Andrei well. Kirill is jealous and in great anger, and he leaves the monastery for the secular world, throwing the accusations of greed in the face of the monks. Andrei leaves for Moscow with his young apprentice Foma. Foma is another creative character, representing the light-hearted and practical-minded commercial artist.

The Passion According to Andrei, 1406:

While walking in the woods, Andrei and Foma have a conversation about Foma’s faults, especially lying. While Foma has talent as an artist, he is less concerned with the deeper meaning of his work and more concerned with practical aspects of the job, like perfecting his azure, a color which in painting was often considered unstable to mix. They encounter Theophanes in the forest, and the old master sends Foma away. During their religious discussion Foma dabs his paint brush in the river as the shot beautifully follows the ink drifting with the waves of the water. We cut to a conversation between Andrei and Theophanes, this time set on a beautiful shot of a stream bank, filled with visuals of water snakes, crawling ants and decomposing swans. Theophanes argues that the ignorance of the Russian people is due to stupidity, while Andrei says that he doesn’t understand how he can be a painter and maintain such views.

“I’d have taken vows of schema long ago and settled down in a cave for good,” says Andrei. In one of my favorite scenes of the film Andrei goes on about the evils of men while it shows a section that contains a reenactment of Christ’s Atonement, which plays as Andrei recounts the story and expresses his faith. “It’s never to late to repent. Of course people are evil, but you cannot blame them altogether. Judas sold the Christ, and remember who bought him. People. We must remind people more often they are people. Russian of the same blood, of the same land. Evil is everywhere. Someone will always sell you thirty pieces of silver. How can God not forgive him of his ignorance?”

The Feast, 1408:

During a nightly walk Andrei encounters a group of naked pagans, whose celebration implies sensuality and lust. Andrei feels attracted by the rituals he witnesses. He is caught spying by the pagans and tied to a cross, and threatens them saying, “Heaven’s fire will consume you! The last judgment awaits!” The pagans decide to drown him in the morning. A woman named Marfa, only dressed with a mantle approaches Andrei. “Why did you threaten us with fire and heaven?” Andrei replies, “It is a sin to go naked and do what you do.” Marfa smiles and says, “What sin? Tonight is for lovemaking. Is sin a love? You might call that the monks who would force us to accept your faith. Do you think it’s easy to live in fear?” She drops her mantle, kisses him and then frees him.

The next morning as Andrei leaves a group of soldiers arrive and round-up the pagans. Marfa escapes by running into the river naked trying to escape by swimming away past Andrei’s boat. “Don’t look, there is nothing to look at”, Andrei tells the others. He and his fellow monks look away in shame as Marfa is slowly fighting for her life.

The Last Judgment, Summer 1408:

Andrei and Danil are working on the decoration of a church in Vladimir. Over months, work is not progressing, as Andrei is doubting himself. He confides to Danil that his task disgusts him and that he is unable to paint a subject such as the Last Judgement, as he doesn’t want to terrify people. He comes to the conclusion that he has lost the ease of mind that an artist needs for his work.

Andrei has a flashback during which he remembers his time working for the Grand Prince, who put out the eyes of artisans to prevent them from reproducing their beautiful work for someone else. That scene is a frightening and disturbing sequence where young Andrei watches these great artists who now become pathetic, blind and helpless. As the flashback ends, Durochka, a mute holy fool wanders into the church. Her feeble-mindedness and innocence leads Andrei to the idea to paint a feast, which finally gives him the idea to finish his painting.

The Raid, Autumn 1408:

While the Grand Prince is away in Lithuania, the Grand Prince’s brother and a group of Tatars raid Vladimir. “The Tatars are coming!!” The invasion and the resulting carnage is shown in great detail. One famous scene shows a horse falling from a flight of stairs and being stabbed by a spear. Another famous scene shows a cow set on fire. The Tatars enter the church. One man is tortured and eventually his face is burned by flames. Andrei prevents the rape of Durochka by a Russian by slaying the perpetrator.

Foma tries to get away but in a heartbreaking scene is shot by an arrow and collapses. Shaken by this horrific event of death and slaughter, Andrei falls into self-doubt and decides to give up painting and takes a vow of silence. He has a dream with the now deceased Theophanes and says what Theophanes said earlier to him was true. Theophanes tells him, “So what if I said it then, you are wrong now, I was wrong than. Through our sins, evil has assumed human form. Encroaching evil means encroaching humanity.”

The Silence, Winter 1412:

Andrei is once again at the Andronikov Monastery. He neither paints nor speaks and keeps Durochka with him. After several years of absence, Kirill shows up at the monastery and asks to be taken in. The father superior allows him to return, but requires him to copy the scriptures fifteen times.

One day, Tatars stop at the monastery while traveling through. One of the Tatars takes Durochka away as his eighth wife, and as much as Andrei tries to stop her from going she resists. He is told by Kirill that, “they wouldn’t dare hurt a holy fool.”

The Bell, Spring-Summer-Winter-Spring 1423–1424:

Andrei’s life turns around when he witnesses the casting of a bell for the Grand Prince. As the bellmaker has died, his son Boriska tells the Prince’s men that he is the only one who possesses his father’s secret of casting a bell. Boriska is another creative character. He is aware of his own importance and the difficult task at hand. He is able to create through a combination of natural skill and pure faith. Boriska supervises the digging of the pit, the selection of the clay, the type of mold, the firing of the furnaces and the hoisting of the bell. During the process the bell-making endeavor grows into a large, costly effort with many workers and Boriska’s making several risky decisions, guided by his instinct. At one point, he privately asks God for help. Andrei watches this young man and is impressed by his strong artistic heart. Halfway through the sequence the skomorokh from the first sequence makes a reappearance and threatens to kill Andrei, whom he mistakes for the man who denounced him years earlier. Kirill steps in and intervenes on behalf of the silent Andrei. Later Kirill confesses privately to Andrei that his sinful envy of Andrei’s talent dissipated once he heard Andrei had abandoned painting and that it was he who denounced the skomorokh.

In the last hour of the film, Boriska, a young inspiring and daring artist is ordering the Grand Prince’s men how to build a church bell from the secrets of his great father. The last scene of the film when the bell-making proceeds toward its end Boriska’s decisive confidence slowly transforms into a stunned, detached disbelief that he’s succeeded at the task. The work crew takes over as Boriska makes repeated, nervous attempts to fade into the background of the activity. Once the bell has been hoisted into its bell tower the Grand Prince and his entourage arrive for the inaugural ceremony.

As the bell is ready to be rung the royal entourage is overhead discussing its doubts that the bell will ring. It’s revealed that Boriska and the work crew know if the bell fails to ring the Grand Prince will have them all beheaded. (We also overhear that the Grand Prince had his brother, who raided Vladimir in The Raid sequence, beheaded.)There is a quiet, agonizing tension as the foreman slowly coaxes the bell’s clapper back and forth, nudging it closer to the lip of the bell with each swing. We pan across the assembly and see Durochka, robed in white leading a horse (preceded by a boy, presumably her son) as she walks through the crowd. At the critical moment the bell rings perfectly she smiles.

After the ceremony Andrei finds Boriska collapsed on the ground, sobbing as he finally admits that “his father never really told him the secret of casting a bell.” Andrei sees this and comforts him, finally breaking his vow of silence. “You see, it’s turned out very well. Lets go together you and I. You’ll cast bells. I’ll paint icons. You’ve brought them such joy and your crying. Come on…come on…”

PRODUCTION NOTES

In 1961, while working on his first feature film Ivan’s Childhood, Tarkovsky made a proposal to Mosfilm for a film on the life of Russia’s greatest icon painter, Andrei Rublev. The contract was signed in 1962 and the first treatment was approved in December 1963. Tarkovsky and his co-screenwriter Andrei Konchalovsky worked for more than two years on the script, studying medieval writings and chronicles and books on medieval history and art. In April 1964 the script was approved and Tarkovsky began working on the film. At the same time the script was published in the influential film magazine Iskusstvo Kino, and was widely discussed among historians, film critics and ordinary readers.

The discussion on Andrei Rublev centered on the sociopolitical and historical, and not the artistic aspects of the film. According to Tarkovsky, the original idea for a film about the life of Andrei Rublev was due to the film actor Vasily Livanov. Livanov proposed to write a screenplay together to Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky while they were strolling through a forest on the outskirts of Moscow. He also mentioned that he would love to play Andrei Rublev. Tarkovsky did not intend the film to be a historical or a biographical film about Andrei Rublev. Instead, he was motivated by the idea of showing the connection between a creative character’s personality and the times through which he lives. He wanted to show an artist’s maturing and the development of his talent. He chose Andrei Rublev for his importance in the history of Russian culture. Tarkovsky cast Anatoli Solonitsyn for the role of Andrei Rublev. At this time Solonitsyn was an unknown actor at a theater in Sverdlovsk. According to Tarkovsky everybody had a different image of the historical figure of Andrei Rublev, thus casting an unknown actor who would not remind viewers of other roles was his favoured approach.

Solonitsyn, who had read the film script in the film magazine Iskusstvo Kino, was very enthusiastic about the role, traveled to Moscow at his own expense to meet Tarkovsky and even declared that no one could play this role better than him. Tarkovsky felt the same, saying that “with Solonitsyn I simply got lucky”. For the role of Andrei Rublev he required “a face with great expressive power in which one could see a demoniacal single-mindedness”. To Tarkovsky, Solonitsyn provided the right physical appearance and the talent of showing complex psychological processes.

Tarkovsky chose to shoot the main film in black and white and the epilogue, showing some of Andrei Rublev’s icons, in color. In an interview he motivated his choice with the claim that in everyday life one does not consciously notice colors. Consequently Rublev’s life is in black and white, whereas his art is in color. The film was thus able express the co-dependence of an artist’s art and his personal life. The color sequence of Rublev’s icons begins with showing only selected details, climaxing in Rublev’s most famous icon, The Trinity. One reason for including this color final was, according to Tarkovsky, to give the viewer some rest and to allow him to detach himself from Rublev’s life and to reflect. The film finally ends with the image of horses at river in the rain. To Tarkovsky horses symbolized life, and including horses in the final scene (and in many other scenes in the film) meant that life was the source of all of Rublev’s art

Filming did not begin until April 1965, one year after approval of the script. The initial budget was 1.6 million Rubles, but it was cut several times to one million Rubles. As a result of the budget restrictions several scenes from the script were cut, including an opening scene showing the Battle of Kulikovo. Other scenes that were cut from the script are a hunting scene, where the younger brother of the Grand Prince hunts swans, and a scene showing peasants helping Durochka giving birth to her Russian-Tatar child. In the end the film cost 1.3 million Rubles, with the cost overrun due to heavy snowfall, which disrupted shooting from November 1965 until April 1966. The film was shot on location, on the Nerl River and the historical places of Vladimir/Suzdal, Pskov, Izborsk and Pechory.

Filming did not begin until April 1965, one year after approval of the script. The initial budget was 1.6 million Rubles, but it was cut several times to one million Rubles. As a result of the budget restrictions several scenes from the script were cut, including an opening scene showing the Battle of Kulikovo. Other scenes that were cut from the script are a hunting scene, where the younger brother of the Grand Prince hunts swans, and a scene showing peasants helping Durochka giving birth to her Russian-Tatar child. In the end the film cost 1.3 million Rubles, with the cost overrun due to heavy snowfall, which disrupted shooting from November 1965 until April 1966. The film was shot on location, on the Nerl River and the historical places of Vladimir/Suzdal, Pskov, Izborsk and Pechory.

Several scenes within the film depict violence, torture and cruelty toward animals, leading to controversy and censorship attempts upon completion of the film. Most of these scenes took place during the raid of Vladimir, showing for example the blinding and the torture of a peasant. Most of the scenes involving cruelty toward animals were simulated. For example, during the Tatar raid of Vladimir a cow is set on fire. In reality the cow had an asbestos-covered coat and was not physically harmed; however, one scene depicts the real death of a horse. The horse falls from a flight of stairs and is then stabbed by a spear. To produce this image, Tarkovsky injured the horse by shooting it in the neck and then pushed it from the stairs, causing the animal to falter and fall down the flight of stairs. From there, the camera pans off the horse onto some soldiers to the left and then pans back right onto the horse, and we see the horse struggling to get its footing having fallen over on its back before being stabbed by the spear. The animal was then shot in the head afterward off camera. This was done to avoid the possibility of harming what was considered a lesser expendable, highly-prized stunt horse. The horse was brought in from a slaughterhouse, killed on set, and then returned to the abattoir for commercial consumption.

In a 1967 interview for Literaturnoe obozrenie, interviewer Aleksandr Lipkov suggested to Tarkovsky that “the cruelty in the film is shown precisely to shock and stun the viewers. And this may even repel them.” In an attempt to downplay the cruelty Tarkovsky responded: “No, I don’t agree. This does not hinder viewer perception. Moreover we did all this quite sensitively. I can name films that show much more cruel things, compared to which ours looks quite modest.”

The first cut of the film was completed in July 1966 and was named The Passion According to Andrei and ran 205 minutes. Goskino demanded cuts to the film, citing its length, negativity, violence, and nudity. After Tarkovsky completed this first version, it would be five years before the film was officially released in the Soviet Union. The ministry’s demands for cuts first resulted in a 190-minute version. Despite Tarkovsky’s objections expressed in a letter to Alexey Romanov, the chairman of Goskino, the ministry demanded further cuts, and Tarkovsky trimmed the length to 186 minutes. The film premiered with a single screening at the Dom Kino in Moscow in 1966 for film professionals. Audience reaction was enthusiastic, despite some criticism of the film’s naturalistic depiction of violence. In February 1967, Tarkovsky and Alexei Romanov complained that the film was not yet approved for an official release and refused to cut further scenes from the film. Tarkovsky’s refusal resulted in Andrei Rublev not being released for years, despite being a topic of discussion at the top level of Mosfilm, Goskino and even during a meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Andrei Rublev was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1967 as part of a planned retrospective of Soviet film on occasion of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. The official answer was that the film was not yet completed and could not be shown at the film festival. A second invitation was made by the organizers of the Cannes Film Festival in 1969. Soviet officials accepted this invitation, but they only allowed the film to screen at the festival out of competition, and it was screened just once at 4 A.M. on the final day of the festival. Audience response nevertheless was enthusiastic, and the film won the FIPRESCI prize. Soviet officials tried to prevent the official release of the film in France and other countries, but were not successful as the French distributor had legally acquired the rights in 1969.

In the Soviet Union, influential admirers of Tarkovsky’s work—including the film director Grigori Kozintsev, the composer Dmitri Shostakovich and Yevgeny Surkov, the editor of Iskusstvo Kino began pressuring for the release of Andrei Rublev. Tarkovsky and his second wife, Larisa Tarkovskaya wrote letters to other influential personalities in support of the film’s release, and Larisa Tarkovskaya even went with the film to Alexei Kosygin then the Premier of the Soviet Union.

Despite Tarkovsky’s refusal to make further cuts, Andrei Rublev finally was released on December 24, 1971 in the 186-minute 1966 version. The film was released in 277 prints and sold 2.98 million tickets. When the film was released, Tarkovsky complained in his diary that in the entire city not a single poster for the film could be seen but that all theaters were sold out.

Despite the cuts having originated with Goskino’s demands, Tarkovsky ultimately endorsed the 186-minute cut the film over the original 205-minute version: “Nobody has ever cut anything from Andrei Rublev. Nobody except me. I made some cuts myself. In the first version the film was 3 hours 20 minutes long. In the second — 3 hours 15 minutes. I shortened the final version to 3 hours 6 minutes. I am convinced the latest version is the best, the most successful. And I only cut certain overly long scenes. The viewer doesn’t even notice their absence. The cuts have in no way changed neither the subject matter nor what was for us important in the film. In other words, we removed overly long scenes which had no significance. We shortened certain scenes of brutality in order to induce psychological shock in viewers, as opposed to a mere unpleasant impression which would only destroy our intent. All my friends and colleagues who during long discussions were advising me to make those cuts turned out right in the end. It took me some time to understand it. At first I got the impression they were attempting to pressure my creative individuality. Later I understood that this final version of the film more than fulfils my requirements for it. And I do not regret at all that the film has been shortened to its present length.”

And yet in 1973, the film was shown on Soviet television in a 101-minute version that Tarkovsky did not authorize. Notable scenes that were cut from this version were the raid of the Tartars and the scene showing naked pagans. The epilogue showing details of Andrei Rublev’s icons was in black and white as the Soviet Union had not yet fully transitioned to color TV. In 1987, when Andrei Rublev was once again shown on Soviet TV, the epilogue was once again in black and white, despite the Soviet Union having completely transitioned to color TV.

Another difference from the original version of the film was the inclusion of a short explanatory note at the beginning of the film, detailing the life of Andrei Rublev and the historical background.When the film was released in the U.S. and other countries in 1973, the distributor Columbia Pictures cut it by an additional 20 minutes, making the film an incoherent mess in the eyes of many critics and leading to unfavorable reviews. Finally in 1999, Criterion Collection released the original, 205-minute version of Andrei Rublev. (Criterion advertises this version as the “director’s cut,”despite Tarkovsky’s stated preference for the 186-minute version.)

-Wikipedia

ANALYZE

Andrei Rublev which Tarkovsky called a “film of the earth,” is set against the background of 14th century Russia, as the film is only loosely based on the life of the great icon painter, and seeks to depict a bleak and violent portrait of medieval Russia. Tarkovsky wanted to create a film that shows the artist as a world-historic figure as its story is about the essence of art and the importance of faith, showing an artist who tries to find the appropriate response to the tragedies of his time. Too experimental, too frightening, too gory, and too politically complicated, it was not allowed to be released domestically in the officially atheist and authoritarian Soviet Union for years after it was completed except for a single screening in Moscow.

When Andrei Tarkovsky’s dark, startling Andrei Rublev first materialized on the international scene in the late 1960s, it was an apparent anomaly—a pre-Soviet theater of cruelty charged with resurgent Slavic mysticism. Today, Tarkovsky’s second feature seems to prophesy the impending storm. Its greatness as moviemaking immediately evident, Andrei Rublev was the most historically audacious production in the twenty-odd years since Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible. Tarkovsky’s epic—and largely invented—biography of Russia’s greatest icon painter, Andrei Rublev (c. 1360–1430), was a superproduction gone ideologically berserk. Violent, even gory, for a Soviet film, Andrei Rublev is set against the carnage of the Tatar invasions and takes the form of a chronologically discontinuous pageant. The otherworldly hero wanders across a landscape of forlorn splendor—observing suffering peasants, hallucinating the scriptures, working for brutal nobles until, having killed a man in the sack of Vladimir, he takes a vow of silence and gives up painting.

At once humble and cosmic, Tarkovsky called Rublev a “film of the earth.” Shot in widescreen and sharply defined black and white, the movie is supremely tactile—the four elements appearing as mist, mud, guttering candles, and snow. A 360-degree pan around a primitive stable conveys the wonder of existence. Such long, sinuous takes are like expressionist brush strokes; the result is a kind of narrative impasto. From a close-up recording the impact of a horse’s hooves on the surface of a turbid river, Tarkovsky’s camera swivels to reveal a Tatar regiment sweeping across a barren hill. Other times, the camera hovers like an angel over the suffering terrain. The film’s brilliant, never-explained prologue has some medieval Daedalus braving an angry crowd to storm the heavens. Having climbed a church tower, he takes flight in a primitive hot-air balloon—an exhilarating panorama—before crashing to earth.

Tarkovsky began shooting Andrei Rublev in September 1964, two years after his first feature, My Name Is Ivan, won the Golden Lion at Venice and two months before Nikita Khrushchev was deposed. By the time he wrapped in November 1965, the cultural thaw had frozen over. When Rublev was finally completed in August 1966, the ministry demanded deep cuts. The film was too negative, too harsh, too experimental, too frightening, too filled with nudity, and too politically complicated to be released—especially on the eve of the Revolution’s 50th anniversary.

After a single screening in Moscow (the Dom Kino supposedly ringed with mounted police), Rublev was shelved. Trimmed by a quarter of an hour, a cut Tarkovsky would later endorse, Andrei Rublev was scheduled for the 1968 Cannes Film Festival only to be yanked by the Soviets at the last minute. (As the ’68 festival would be disrupted and shut down by French militants, this move was not altogether irrational.) The following year, thanks in part to the agitation of the French Communist Party, Rublev was shown at Cannes, albeit out of competition. Although screened at 4 A.M. on the festival’s last day, it was neverthelessawarded the International Critics’ Prize. Soviet authorities were infuriated; Leonid Brezhnev reportedly demanded a private screening and walked out mid-film.

With questionable legality and over strenuous objections by the Soviet Embassy, Andrei Rublev opened in Paris in late ’69. Ultimately, the Soviet cultural bureaucracy relented, releasing the film domestically in 1971. Two years later, Rublev surfaced at the New York Film Festival, cut another 20 minutes by its American distributor, Columbia Pictures. Time compared the movie unfavorably to Dr. Zhivago; those other New York reviewers who took note begged off explication, citing Rublev’s apparent truncation.

What was there to say? The artist Rublev is introduced, along with two brother monks, taking refuge from a storm in a stable where the peasants are being entertained by a bawdy jester. Such buffoons, one monk observes, are made by the devil; the sequence ends with the clown being arrested. In the next sequence, two monks discuss aesthetics while, outside the church, a prisoner is tortured on the rack. (Later, in a fit of jealousy, one of them will leave his monastery, cursing the devotion to art that has corrupted his brothers.) Later, Rublev refuses to terrorize the faithful by painting a Last Judgment. His principles harm his career; the irony, surely not lost on Tarkovsky, was that, a century after the painter’s death, the Orthodox Church accorded his icons absolute authority, a standard “to be followed in all perpetuity.”

The first (and perhaps only) film produced under the Soviets to treat the artist as a world-historic figure and the rival religion of Christianity as an axiom of Russia’s historical identity, Andrei Rublev is set in the chaotic period that saw the beginning of the national resurgence of which Rublev’s paintingswould become the cultural symbol. Indeed, it was precisely the veneration of icons that would distinguish Russian art from that of the West. As the Renaissance gathered momentum, sacred images were transmuted into secular works of art; Russian paintings, however, remained less representations of the world than embodiments of spirit.

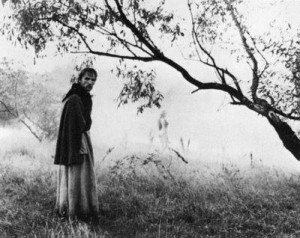

On one hand, Rublev is founded on the conflict between austere Christianity and sensual paganism—whether Slavic or Tatar. On the other, it puts the artist in the context of state patronage and repression. (Tarkovsky originally called the movie The Passion According to Andrei.) When Rublev stumblesupon the late spring mysteries of Saint John’s Eve—an alien rite, delicate and strange, with naked peasants carrying torches through the mist—the monk himself is captured and tied to a cross. One wonderful touch: Andrei inadvertently backs into a smoldering fire and has his robes set, momentarily, aflame.

On the other hand, the film projects an entire world—or rather the sense that, as predicted by André Bazin’s “Myth of Total Cinema,” the world itself is trying to force its way through the screen. Undirectable creatures animate Tarkovsky’s compositions—a cat bounds across a corpse-strewn church, wild geese flutter over a savaged city. The birch woods are alive with water snakes and crawling ants, the forest floor yields a decomposing swan. The soundtrack is filled with bird calls and wordless singing; there’s always a fire’s crackle or a tolling bell in the background.

Andrei Rublev is itself more an icon than a movie about an icon painter. (Perhaps it should be seen as a “moving icon,” in the same sense that the Lumière brothers made “moving pictures.”) This is a portrait of an artist in which no one lifts a brush. The patterns are God’s, a close-up of spilled paint swirling into pond water or the clods of dirt Rublev flings against a whitewashed wall. But no movie has ever attached greater significance to the artist’s role. It’s as though Rublev’s presence justifies creation.

-J. Hoberman

The great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the most difficult directors to grasp. His films are less entertainments and more meditative art. A lot of people say his films are too slow, too long and need extensive trimming in several scenes. But they don’t really ‘see’ what the great artist is trying to portray on the screen. I believe the films he makes which include philosophical and existential dialogue and long extensive takes make audiences relax, slow down and enter his world of complete meditation. Some of his shots would seem like they go on for an unreasonable amount of time, and people can either get bored or instead they can do as I believe Tarkovsky’s intentions are during these slow periods and give our mind a time to consolidate what we’ve just seen, what we’ve just heard, and what we’ve just witnessed. It gives us a chance to look at ourselves and process it in terms of our own reflections.

Andrei Tarkovsky was an artist that sculpted and created his own universe for himself and himself only. Many viewers who aren’t used to the works of Ingmar Bergman, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Robert Bresson or Yasujiro Ozu and are going into a Andrei Tarkovsky film wouldn’t stand a chance of sitting through it. Within twenty minutes of the film I can see most people getting restless and bored. What you have to understand when going into a Tarkovsky film is that you’re not seeing a film but your experiencing the environment. He had a profound undercurrent of spirituality and consciously embodied the idea of a Great Filmmaker, making works that were uncompromisingly serious and ambitious, with no regard whatever for the audience, what the audience wanted or box office records. Andrei Tarkovsky is considered the greatest director to have emerged from Russia since the great director Sergei Eisenstein, and the reason that his films are not as widely known is because they are the most abstract, exhaustive, metaphysical, intellectual films that stem closest to the literary definition of art.

All throughout his film-making career, Tarkovsky, having to deal with the constant struggles with the conservative Soviet regime, could make only a handful of movies, each of which can serve to be a live thesis on spiritualism and theology. Tarkovsky also mastered the use of time and space in cinema that helped him to express what many would think would be inexpressible in film. All throughout his film-making career, Tarkovsky, having to deal with the constant struggles with the conservative Soviet regime, could make only a handful of movies, each of which can serve to be a live thesis on spiritualism and theology, all the while mastering the use of time and space, and expressing what many would think would be inexpressible in the cinema. Tarkovsky, who is often looked as either a pretentious director or a genius, still played an important role in the development of modern art cinema. Tarkovsky’s Cinema like Russian Literature has a close association with poetry. In fact, the best way to describe his films are… as poetry. Tarkovsky’s ability to create beautiful composition shots with gorgeous landscapes of nature and philosophical discussions on the existence of man brings a meditative dimension to his style of filmmaking. Tarkovsky, like any great artist, always strived for perfection and his uncompromising ambition. He was known to be very direct and straightforward in matters that related to his films.

Andrei Rublev was Tarkovsky’s second film and not only is it his greatest achievement but one of the greatest art films about an artist ever made. The greatness and epic scope of Andrei Rublev is quite evident right from the breathtaking epilogue sequence in the film in which it shows a medieval Daedalus braving an angry crowd as he storm the heavens. Having climbed a church tower, he takes flight in a primitive hot-air balloon and hovers like an angel above the suffering terrain, only to crash back down to earth. This sequence reminded me of the beginning traffic jam in Federico Fellini’s 8½ where the film director Guido is hovering high into the sky and his press agent is pulling him back to land. The sequence of the air balloon serves as a similar metaphor on how governments control and own the artistic freedoms of others who try to break free from such constraints. Andrei Rublev is one of the greatest films about a man’s artistic freedom and integrity, in the face of repressive authority, hypocrisy, technology and empiricism by which knowledge is acquired on one’s own without reliance on authority, and the role of the individual, community, and government in the making of both spiritual and epic art.

Tarkovsky also creates long sinuous camera takes with expressionist brush strokes as you calmly participate in the existential themes of the nature of art and the questions of God. In one of my favorite scenes in the film Andrei and Theophanes have a deep existential conversation, on a beautiful stream bank, as the camera pans across such haunting visuals of water snakes, crawling ants and a decomposing swan. While Andrei and Theophanes are having their discussion young Foma dabs his paint brush in the river as the shot beautifully follows the ink drifting with the waves of the water. When Andrei goes on about the evils of men Tarkovsky subtly cuts to a reenactment of Christ’s Atonement, which plays as Andrei recounts the story and expresses his theories of faith.

The scene where the pagans are getting rounded up and killed by the soldiers makes for one of the most fascinating scenes in the film. When Marfa escapes by running into the river naked and swims away past Andrei’s boat, Andrei turns away and says, “Don’t look, there is nothing to look at”. I find it ironic that Marfa was forgiving enough to look past Andrei’s belief differences and let him go in the earlier scene, and yet when it comes to Andrei saving her, Andrei decides to not involve himself. To Tarkovsky horses symbolized life, and including horses in the final scene (and in many other scenes in the film) meant that life was the source of all of Rublev’s art. This style that he created eventually lead to a book titled Sculpting In Time, which was a book Andrei Tarkovsky wrote about art and cinema in general, and his own films in particular. It was originally published in 1986 in German shortly before the author’s death. The title refers to Tarkovsky’s own name for his style of film-making. The book’s main statement about the nature of cinema is summarized in the statement, “The dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame.” Tarkovsky describes his own distaste for the growing popularity of rapid-cut editing and other devices that he believes to be contrary to the true artistic nature of the cinema.

With watching Tarkovsky’s films there’s always something to contemplate about afterwards and I believe Andrei Rublev, Stalker, Solaris and The Mirror are his masterpieces. He started out with an ambitious war film titled Ivan’s Childhood which looks at war through the eyes of a young boy. His next project was the sci-fi classic Solaris which is commonly called Tarkovsky’s reply to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey. Both of those films involve similar themes of space journeys and encounters with unknown intelligence but Kubrick’s film was more cold and disconnected where Tarkovsky’s was more human, organic and more in touch with each inhabitant. He then did a film called The Mirror which is a sort of labyrinth full of symbolism and dream imagery set in several different time lines of one persons life. His next masterpiece was Stalker which I consider almost on par with Andrei Rublev, which is about a “stalker” a man who is paid to take a writer and professor to the center of the “zone”, which is a certain part in the wilderness where the laws of physics no longer apply, and if they survive and make it to the center can get there wishes granted. His last two films were Nostalghia and The Sacrifice but unfortunately Tarkovsky died in his 50’s after making only seven films. His last film The Sacrifice reflects Tarkovsky’s large respect for the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. It was set in Sweden on the island of Gotland, close to Fårö, where many of Bergman’s films had been shot. He wanted to do it on Fårö, but was denied access by the military.

Tarkovsky’s films are extremely meditative and so when watching the great Andrei Rublev for the third time I noticed a lot of quiet poignant moments. His films are uncompromising meditations on human nature and the purpose of existence which closely resemble the themes of Bergman and Bresson. He once said, “I am only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson and one called Bergman.” When watching any of his seven films you really have to sit and listen because you can hear sounds that he greatly repeats in the backgrounds of all of his work. The soundtrack and its sounds are an important function in Andrei Rublev, and is large part of Tarkovsky’s full meditative effect. The film is filled with bird calls and wordless singing and there’s always a fire’s crackle or a tolling bell ringing in the background. Tarkovsky films are something that when your going into you are expected to sit, wait and listen. A lot of his films have sounds of dripping of water or rain, the sound of owls, birds, the wind blowing, the birds chirping, horses running, blowing leaves and hens crowing which are a key part when experiencing a Tarkovsky film. All his films were visually stunning as well and very philosophical with his questions of God and the existence of human nature. A large reason why Andrei Rublev is one of my favorite films is due in large part of its ending. The extraordinary sequence in which we are witnessed to watch men work together to mold and create a large holy bell is one of the great scenes in film history and reminded me of the moments in the great Werner Herzog epic Fitzcarraldo; which was a story about men ordered to build and create an opera house in the middle of the jungle. The engineering and production of these men creating this artistic vision imagined by a boy is something no film today with its CGI or special effects could ever reproduce. It is a magical scene that shows an artist with a vision can create what he always had dreamed. When Andrei Rublev watches this brave naive boy order hundreds of men to mold, clay and create this exhilarating project that the boy had envisioned within his heart through pure faith, it touched me on so many levels and was one of the most inspirational scenes I have ever witnessed in motion picture history. There is a quiet, agonizing tension as the foreman slowly coaxes the bell’s clapper back and forth, nudging it closer to the lip of the bell with each swing, and then comes the sound of the bell. This final scene in the film is probably the greatest scene I’ve ever experienced of a man confronting his love for his art and of his sins of the life he has led. After the bell successfully rings for the world to hear Andrei Rublev finally breaks out of his silence and finds a reason to continue his art again, because he then realizes that great art brings people great love. After the ceremony Andrei finds Boriska collapsed on the ground, sobbing as he finally admits that “his father never really told him the secret of casting a bell.” Andrei sees this and comforts the boy, finally breaking his vow of silence. “You see, it’s turned out very well. Lets go together you and I. You’ll cast bells. I’ll paint icons. You’ve brought them such joy and your crying. Come on…come on…” Despite Andrei Rublev’s unfortunate theatrical release critics have now come to realize the importance the film is to art cinema. Andrei Rublev has been recently honored again when it came equal second in a U.K. newspaper series “Greatest Films of All Time” as voted by critics from The Guardian and The Observer, and is currently ranked as the second most spiritually significant film of all time by the Arts and Faith online community and it was ranked #87 in Empire magazines The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema in 2010.

Tarkovsky’s films are extremely meditative and so when watching the great Andrei Rublev for the third time I noticed a lot of quiet poignant moments. His films are uncompromising meditations on human nature and the purpose of existence which closely resemble the themes of Bergman and Bresson. He once said, “I am only interested in the views of two people: one is called Bresson and one called Bergman.” When watching any of his seven films you really have to sit and listen because you can hear sounds that he greatly repeats in the backgrounds of all of his work. The soundtrack and its sounds are an important function in Andrei Rublev, and is large part of Tarkovsky’s full meditative effect. The film is filled with bird calls and wordless singing and there’s always a fire’s crackle or a tolling bell ringing in the background. Tarkovsky films are something that when your going into you are expected to sit, wait and listen. A lot of his films have sounds of dripping of water or rain, the sound of owls, birds, the wind blowing, the birds chirping, horses running, blowing leaves and hens crowing which are a key part when experiencing a Tarkovsky film. All his films were visually stunning as well and very philosophical with his questions of God and the existence of human nature. A large reason why Andrei Rublev is one of my favorite films is due in large part of its ending. The extraordinary sequence in which we are witnessed to watch men work together to mold and create a large holy bell is one of the great scenes in film history and reminded me of the moments in the great Werner Herzog epic Fitzcarraldo; which was a story about men ordered to build and create an opera house in the middle of the jungle. The engineering and production of these men creating this artistic vision imagined by a boy is something no film today with its CGI or special effects could ever reproduce. It is a magical scene that shows an artist with a vision can create what he always had dreamed. When Andrei Rublev watches this brave naive boy order hundreds of men to mold, clay and create this exhilarating project that the boy had envisioned within his heart through pure faith, it touched me on so many levels and was one of the most inspirational scenes I have ever witnessed in motion picture history. There is a quiet, agonizing tension as the foreman slowly coaxes the bell’s clapper back and forth, nudging it closer to the lip of the bell with each swing, and then comes the sound of the bell. This final scene in the film is probably the greatest scene I’ve ever experienced of a man confronting his love for his art and of his sins of the life he has led. After the bell successfully rings for the world to hear Andrei Rublev finally breaks out of his silence and finds a reason to continue his art again, because he then realizes that great art brings people great love. After the ceremony Andrei finds Boriska collapsed on the ground, sobbing as he finally admits that “his father never really told him the secret of casting a bell.” Andrei sees this and comforts the boy, finally breaking his vow of silence. “You see, it’s turned out very well. Lets go together you and I. You’ll cast bells. I’ll paint icons. You’ve brought them such joy and your crying. Come on…come on…” Despite Andrei Rublev’s unfortunate theatrical release critics have now come to realize the importance the film is to art cinema. Andrei Rublev has been recently honored again when it came equal second in a U.K. newspaper series “Greatest Films of All Time” as voted by critics from The Guardian and The Observer, and is currently ranked as the second most spiritually significant film of all time by the Arts and Faith online community and it was ranked #87 in Empire magazines The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema in 2010.

“My discovery of Tarkovsky’s first film was like a miracle. Suddenly I found myself standing at the door of a room, the keys to which, until then, had never been given to me. It was a room I had always wanted to enter and where he was moving freely and fully at ease. I felt encouraged and stimulated: someone was expressing what I had always wanted to say without knowing how. Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

-Ingmar Bergman