Amarcord (1973)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Amarcord Fellini” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]If there ever was a film that was made entirely out of nostalgia, joy and straight from the heart it would have to be Federico Fellini’s Amarcord, which was the winner of the Foreign Language Oscar in 1973 and considered by many to be Fellini’s last ‘great film.’ Amarcord means ‘I remember’ which is in the dialect of Rimini and is set in Borgo San Giuliano, a small seaside town of Fellini’s youth which is located in the province of Emilia-Romagna in 1930s Fascist Italy. Even though many of the things portrayed in the film were things experienced by the young Fellini, this is not necessarily an autobiography because many of these memories have been transformed, exaggerated and even fabricated within the dreamlike fantasy of its storytelling. Fellini, was said by many to be a great liar and storyteller who denied the origin of the Amarcord dialect claiming it instead was a mysterious, cabalistic word, that was linked to invention rather than memory. Amarcord involves many of these ideas of memory and invention where all of the character’s within the fictional town of Borgo all seem to be larger than life and slight caricatures of themselves. Fellini had a love and a fascination for the circus and Amarcord feels like one long circus dance number, which is constructed like a guided tour giving the audience several different series of events within the small town of Borgo, including the glories of grand hotels and ocean liners, and the play-acting of Mussolini’s fascist costume party parade. [fsbProduct product_id=’731′ size=’200′ align=’right’]The town is in itself a character in the film, as we see the everyday rituals and routines of the village of Borgo; which starts with one spring and ends with the beginning of a another. The town is inhabited with several lively and colorful character’s within the structure of the story including the town idiot who happily recites poems and fabricated lies, a blind accordion player who is relentlessly tormented by the schoolboys, a stringy blond nymphomaniac whore, sexually curious and mischievous schoolboys, the local priest who obsesses over masturbation, a buxom tobacconist clerk whom the schoolboys happily enjoy masturbating too; and the quirky and colorful Biondi family, who never fail to have a dull moment between one another; If they don’t strangle each other first. Amarcord is a masterful comedy-drama and has not only some of the greatest comedic moments in all of Italian film but a prank that I would rank as one of the most ingenious constructed classroom pranks in all of film history.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”Amarcord Fellini” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]If there ever was a film that was made entirely out of nostalgia, joy and straight from the heart it would have to be Federico Fellini’s Amarcord, which was the winner of the Foreign Language Oscar in 1973 and considered by many to be Fellini’s last ‘great film.’ Amarcord means ‘I remember’ which is in the dialect of Rimini and is set in Borgo San Giuliano, a small seaside town of Fellini’s youth which is located in the province of Emilia-Romagna in 1930s Fascist Italy. Even though many of the things portrayed in the film were things experienced by the young Fellini, this is not necessarily an autobiography because many of these memories have been transformed, exaggerated and even fabricated within the dreamlike fantasy of its storytelling. Fellini, was said by many to be a great liar and storyteller who denied the origin of the Amarcord dialect claiming it instead was a mysterious, cabalistic word, that was linked to invention rather than memory. Amarcord involves many of these ideas of memory and invention where all of the character’s within the fictional town of Borgo all seem to be larger than life and slight caricatures of themselves. Fellini had a love and a fascination for the circus and Amarcord feels like one long circus dance number, which is constructed like a guided tour giving the audience several different series of events within the small town of Borgo, including the glories of grand hotels and ocean liners, and the play-acting of Mussolini’s fascist costume party parade. [fsbProduct product_id=’731′ size=’200′ align=’right’]The town is in itself a character in the film, as we see the everyday rituals and routines of the village of Borgo; which starts with one spring and ends with the beginning of a another. The town is inhabited with several lively and colorful character’s within the structure of the story including the town idiot who happily recites poems and fabricated lies, a blind accordion player who is relentlessly tormented by the schoolboys, a stringy blond nymphomaniac whore, sexually curious and mischievous schoolboys, the local priest who obsesses over masturbation, a buxom tobacconist clerk whom the schoolboys happily enjoy masturbating too; and the quirky and colorful Biondi family, who never fail to have a dull moment between one another; If they don’t strangle each other first. Amarcord is a masterful comedy-drama and has not only some of the greatest comedic moments in all of Italian film but a prank that I would rank as one of the most ingenious constructed classroom pranks in all of film history.

PLOT/NOTES

In the breezy wind a young woman is seen hanging clothes on a line. She then notices the arrival of ‘manine’ pullfballs floating on the wind and happily says, “Puffballs! When the puffballs come then winter is almost gone.” The old man pottering beside her replies, “When puffballs come, cold winter’s done.” Throughout the village square of Borgo, schoolboys jump around trying to pluck puffballs out of the air. Giudizio who is the town idiot, looks into the camera and recites a poem saying, “In our town, the puffballs arrive hand in hand with spring. These are the sort of puffballs that drift around, soaring over the cemetery where all rest in peace, soaring over the beachfront and the Germans, newly arrived, who don’t feel the cold. Drifting…drifting…swirling…swirling…”

At the hairdresser’s, a Fascist just gotten his head shaved when Fiorella arrives to accompany her sister Gradisca who is looked at as the village beauty, to the traditional bonfire celebrating spring. As night falls, the inhabitants of Borgo make their way to the village square as all the major towns people are introduced. You have the blind accordion player who is always relentlessly tormented by the schoolboys; Volpina the blond nymphomaniac whore; the large and buxom tobacconist clerk; Titta Biondi the young adolescent protagonist who was based on Fellini’s childhood friend; and Aurelio Biondi, Titta’s short fused working-class father. Aurelio responds in anger to Titta and several other of the schoolboys pranks as they relentlessly light off fireworks. Aurelio says, “one father can take care of 100 kids, but 100 kids can’t take care of one father. That’s the gospel truth.” Aurelio’s wife Miranda Biondi always comes to her son’s defence while Miranda’s brother, Lallo lives with Titta’s family, and sponges off his brother-in-law. There is also Titta’s grandfather, a likeable old man with an eye on the family’s young maid, and a street vendor, Biscein the town’s compulsive liar.

When Volpina arrives to the town square a man says to her, “Volpina, have you made love today? How many men did you service? I bet you even dip a cock in your morning coffee.” Gradisca arrives to the town square with her sister as a man shouts out, “You’re the greatest, Gradisca. Greta Garbo’s got nothing on you! Carrying the old witch and about to burn it. Light the bonfire and burn the old witch!” Giudizio sits an effigy of the ‘Old Witch of Winter’ in a chair on the stack and Gradisca is given the honour of setting it aflame. Lallo maliciously removes the ladder, trapping Giudizio atop the inferno. “I’m burning!” Giudizio screams as the crowd dances gleefully round the bonfire and schoolboys run amuck exploding firecrackers. “Look at that. Your brother really is an asshole,” Aurelio tells his wife. The local aristocrat and his decrepit wife raise a toast to the dying flames. Schoolboys drag Volpina near the cinders then swing her back and forth in rhythm to the blind accordionist’s tune. A motorcyclist roars through the glowing coals in a mindless display of exhibitionism. Black-clothed women scoop the scattered embers into pans as the town lawyer (and the main narrator for the audience) appears walking his bicycle. Like Giudizio, he also addresses the camera saying, “the origins of this town are lost in the mists of time. In the municipal museum, there are stone implements…that date to prehistoric times. I myself have found some graffiti of great antiquity in caves on Count Lovignano’s estate. Be that as it may, the first date we know for certain is 268 BC, when this became a Roman colony and the start of the Emilian Way.” He gets interrupted with obnoxious sounds from the schoolboys and he angrily walks off in a huff. From a window, the Fascist fires his pistol into the air. “I feel spring all over me already,” says Gradisca in awe of the celebration.

Zeus the red-haired crusty schoolmaster, presides over an official class photograph. After showing us a wall hung with the portraits of the king, the pope and Mussolini, the next shot is a sequence of several classroom antics involving Titta, Ovo and Ciccio, the class fat boy who has a crush on Aldina, a lovely brunette. During an art teacher’s lesson on Giotto’s perspective, the art teacher dips a breakfast biscuit in milk. Expanding her voluptuous chest, the math teacher demonstrates an algebraic formula, while the Italian teacher is laughed at by the class because of Ovo’s parody of him. The religion instructor Don Balosa wipes his glasses and drones on while half the class sneaks out for a smoke in the toilets. In one of the best scenes of the film several students in class device a trick where they construct a long tube and a student from far back in the class urinates inside the tube which slowly makes its way to the front to look as if Gigliozzi had done it while being instructed by the teacher.

“Fu Manchu!” cries Volpina, prowling on a sunburnt beach. When workers at Aurelio’s construction site invite her to join them, the foreman promptly sends her off after she says to them that she lost her pussy cat. Mortar, an old brick-maker, is asked to recite his new poem entitled Bricks: My grandfather made bricks…My father made bricks…I make bricks, too…but where’s my house?”

The next scene shows the everyday life of the Biondi home as Aurelio comes home from a hard day at work enraged when finding out Titta urinated on the neighbor’s hat. His shouting during dinner with his wife Miranda becomes a verbal domestic argument between the two of them in front of the rest of the family; and by the reaction of the family, they seem to be used to this domestic routine. While the children are gobbling up their food Miranda tells them, “are you bottomless pits or what? Anyone would think I never fed you!” When Aurelio asks Titta where he was the other night Titta explains that he was at the movies watching an American western and when Titta describes the story to his father on how it was a bloody massacre between the cowboys and Indians his father jumps up and angrily chases him out of the house yelling, “I’ll massacre you, you little hooligan! I’ll put you in the hospital!” Miranda follows the both of them outside and Aurelio asks her, “you have to tell me who fathered this piece of shit! At his age I’d already be working for three years!” Miranda demands Aurelio to come inside and leave their son alone saying, “everyone in town laughs at us, even the roosters.” Aurelio goes back into the house with Miranda and the two of them verbally go at it again and Miranda snaps and says, “I can’t stand any more! I’m going crazy! I’m going mad! I’ll kill the whole lot of you! I’ll put strychnine in your soup! That’s what I’ll do!” During this domestic argument the children continue to calmly eat their dinner while Uncle Pattacca excuses himself from the dinner table and walks into the other room and quietly says, “one…two…three…” as he passes gas three separate times.

The next day Titta and his school gang follow Gradisca on her promenade under the arcades making remarks about her large behind and she quickly turns around and yells, “You’ll get a purse over your head!” Later on the school gang then decide to flatten their noses against an irritated merchant’s shop window with the merchant saying, “If I shot them they’d call me a murderer. I’ll throw them all in a pit of lime!” Lallo and his fellow Don Juans spot a carriage-load of new prostitutes passing them by on the road heading to the local brothel and the news spreads like wildfire to the town’s male population.

The main concerns of Don Balosa, who doubles as the town priest, are floral arrangements and also making sure his schoolboys avoid masturbation. Young Titta is about to head to confession but before he leaves his mother tells him he can’t receive communion if he had anything to drink. She then says “And tell him that you’re a delinquent, that you upset your mother and father, and that you answer back. And that you curse everything, understand? Everything!”

At confession Don Balosa warns Titta saying, “Saint Louis cries when you touch yourself.” Titta tells Don Balosa how his parents mistreat him and how he is forced to lie while Don Balosa strangely sniffs his fingers. When Don Balosa asks Titta if he has touched himself Titta can’t come out and be honest with him as Titta thinks to himself about all the fantasies that he has daily including not only the buxom tobacconist and the sensual math teacher but also the fat bottomed peasant women him and his schoolmates watch from afar. Titta flashes back to the love of his life Gradisca and how he actually tried to grope her at the Cinema Fulgor while she smoked watching her biggest crush Gary Cooper on the movie screen. When he put his arm on her knee Gradisca coldly turned to him and asked if he’s looking for something; which greatly embarrassed Titta. Titta’s personal monologue with himself in confession in front of Father Balosa is one of the funniest scenes in the film: “I’m not gonna tell you. You’ll only tell Dad. Don’t tell me you don’t touch yourself. How can you not, when you see the woman in the tobacco shop, as stacked as she is and she says…’Export brand?’ And the math teacher who looks just like a lion? Mother of God! How can you not touch yourself when she looks at you that way? What do you think we come to see on St. Anthony’s day, when they bless the animals? The sheep’s butts? See how he’s looking at me. How can I tell him about Volpina and the time I pumped her tires? Then there’s Gradisca. Father Balosa can’t understand these things. But since I had to say something, I said I’d touched myself once, just a little, but that I regretted it immediately. He was happy with that. I had to say three Our Fathers, Hail Marys and Glorias, and that was it.”

In an extended humorous confession scene Gigliozzi confesses on how he touched himself while in a parked car with Titta, Ciccio, and Ovo. All four of them were inside a parked car within a garage as they all masturbated and vocally shout out the various women they are fantasizing about like famous American actress Jean Harlow, the tobacco lady and her large breasts and a random girl they’ve seen at the circus with fish net stockings. When Gigliozzi shouts out Aldina, Ciccio get’s furious because that’s the girl of his dreams and he smacks Gigliozzi and says, “No. Aldina’s mine! I’ll smack your face!” while the car is shown shaking and rattling from the outside.

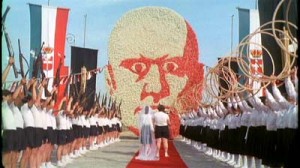

“Comrades. Hail II Duce!” is announced with the visit of the federal during a parade led by the local gerarca. Following behind him are is math teacher and her colleagues, rejuvenated by Fascist rhetoric. “Let me touch them. I want to touch them. Long live II Duce!” shouts Gradisca in complete awe. Now in uniform, Lallo joins the parade shouting “Mussolini’s got balls this big!” During the march in town the lawyer says to the audience, “Today, April 21st, we celebrate the birth of Rome, the Eternal City. What does that mean? That we must respect the monuments, the ruins that Rome has left us, which is what I’ve done all along, despite being razzed at night.” Aurelio is at home as he argues with his wife Miranda about wanting to head to the rally, but she doesn’t let him get through the gate. “Why is it that whenever there’s a rally, I have to stay home? This is the last straw!” he shouts.

Watching the rally, Ciccio starts to daydream that he is standing before the giant face of Mussolini, who blesses him and his Fascist bride, Aldina. Surreptitiously wired into the bell tower of the town church, a gramophone plays a recording of the Internationale but it is soon shot at and destroyed by gun-crazy Fascists.

Later that evening Aurelio is brought in for questioning because of his suspicious anarchist past. The Fascists question Aurelio on why he doesn’t give the Roman salute and that he is known to have talked down on Mussolini which the soldiers consider a threat or a lack of faith in Fascism. Aurelio is than asked to drink a toast to the triumph of Fascism but when Aurelio realizes that the drink is castor oil the Fascists force the castor oil down his throat calling him a disgrace. When Aurelio limps home later that evening in a nauseous state Miranda draws him a bath and Aurelio angrily yells, “If the person who squealed is who I think is was, he’d better move to another continent or I’ll eat his guts out! I’ll have his balls for dinner!” It is discovered that it was in fact Lallo who betrayed him.

The next day the lawyer appears in the Grand Hotel calling it ‘the Old Lady’ and saying to the audience, “I come here every year to sip the nectar of love, I offer tenderness and yearn for tenderness in return. I’m the only one in town who visits the Grand Hotel. They say Gradisca was here once, and it was because of that highly improbable adventure that she came to be called Gradisca. Her real name is Ninola. But one winter night three years ago…” The film flashes to a story of Gradisca as she is encouraged to bed the Fascist high official in return for government funds to rebuild the town’s harbor. After the story the lawyer says, “Mind you, I don’t attribute much truth to that story, nor to the one that Biscein tells. He’s a born liar. He makes up a new one every day.” The lawyer then recounts Biscein story on the night he made love to twenty-eight women in the visiting sultan’s harem as the lawyer says, “He claims that, between the beautiful girls and the ugly ones, he polished off 28 of them that night.” The lawyer then goes into the backdrop on the Grand Hotel and of Lallo’s gang of mother-controlled layabouts who obsessively pursue middle-aged female tourists.

One summer afternoon, the family visits Uncle Teo, Aurelio’s brother, confined to an insane asylum. They take him out for a day in the country, during the carriage ride Teo asks to pull over to pee and instead pees in his pants. When the Biondi family arrives in the country Teo is left alone for a short moment and when some family members return they realize Teo decided to climb high up a tree. While up there Teo starts repeatedly yelling, “I want a woman! I want a woman!” The grandfather asks Teo, “Where am I going to find you a woman, my boy?” The family rushes over and tries to tell Teo to come back down because he could fall and break his neck but he refuses to listen and keeps repeating “I want a woman!” The grandfather says, “Quite a normal urge, actually. He’s 42 years old. When I was 42…” The Biondi family get a ladder and try to climb up the tree and grab him but Teo starts to throw stones that he carried earlier in his pocket. “Christ, what’ll I do now? Jerk off!” yells Aurelio upset at his loony brother for getting stuck up a tree and refusing to get down. “Were going home. Come on, everyone. We’re going home,” Aurelio demands. But no one in the family wants to abandon Teo up in the tree. Aurelio tells Miranda to go back to the hospital and retrieve some nurses while the family patiently waits there having to keep hearing Teo shouting, “I want a woman!” Aurelio can’t take it anymore saying, “make him shut up!” Titta offers his father an idea that maybe he should go retrieve Volpina but his father scoffs at his advice. A dwarf nun and two orderlies finally arrive on the scene and when the nun marches up the ladder Teo obediently agrees to finally come down and return to the asylum. A doctor tells Aurelio, “some days he’s normal, some days not. Just like the rest of us.”

The next scene is the town’s inhabitants embarking in small boats to meet the passage of the SS Rex, the regime’s proudest technological achievement. By midnight many have fallen asleep waiting for its arrival while Aurelio is looking at the stars and says to his family, “look how many there are. Millions and millions and millions of stars. Jesus Christ! I wonder how they all stay in place up there. I mean, it’s pretty simple for us. To build a house, we use so many bricks, so much lime. But up there, sweet Jesus! Where do you put the foundations! They’re not made of confetti, you know.” Gradisca starts to open up about her real age and how she still isn’t married yet and starts to cry saying, “I want one of those encounters that last a lifetime. I want a family, children, a husband to chat with in the evening over coffee, maybe, and to make love with now and then, because when you must, you must. But affection is even more important than love, and I’m so full of affection. But who can I give it to? Who will take it?” Awakened by a foghorn, everyone watches in awe as the Rex liner finally arrives and sails past, capsizing their boats in its wake with everyone from their boats shouting, “Hurray for the Rex! The greatest thing the regime ever built!”

In a very surreal scene Titta’s grandfather wanders lost in a disorienting fog so thick it seems to smother his own house and the autumnal landscape. Walking out to the Grand Hotel, Titta and his friends find it boarded up. Like zombies, they waltz on the terrace with imaginary female partners enveloped in the fog and of the light wind. The scene then jumps to an annual car race which also provides the occasion for Titta to daydream of winning the grand prize which is Gradisca, and driving off with her.

One evening the buxom tobacconist is about to close up shop when Titta tries to catch a cigarette. She ignores him but he catches her interest by boasting that he can lift her up. Daring him to try, she’s aroused when he succeeds saying to him,”You’ll drop me, you crazy boy!” Setting her back down, he goes to sit breathlessly in a corner as she draws the shop’s iron shutter and exposes a breast, overwhelming Titta by her sheer size. The teenager’s awkward efforts end with him being suffocated by the very objects of his desire with her sexually turned on saying, “Drive me crazy…just a little. Suck. Come on.” She pulls out her other breast and says, “you can have this one too. Don’t blow! Suck! You have to suck you idiot.” She suddenly loses all interest, and sends him away after giving him the cigarette for free; but not before Titta humorously asks her to help him lift up the iron shutter.

On the cusp of winter, Titta falls sick and is tended by his mother. While bedridden Titta asks his mother how she met and married dad. Miranda tells him that Aurelio didn’t come from much money and the two of them eloped without her parents approval. Because of Titta’s illness he starts rambling incoherently about how he will become a doctor in Africa and will prove Gradisca wrong.

One day it starts snowing and all the towns people run out and c elebrate. The snow increases over the next four days and the townspeople start to go out and shovel the roads. The Lawyer peers out from behind a snow bank and says to the audience, “This will go down as the Year of the Big Snow. With the exception of the Ice Age, it’s never snowed this heavily in our town.” He suddenly gets hit by a snow ball and says, “That must’ve been some young boy, not the usual guy. As I was saying, the exceptional years were 1541, 1694, 1728, 1888, when, against all odds, it snowed on July 13th,” as another snowball flies at him and he quickly flees. As Gradisca makes her way to church in the town square, Titta follows in hot pursuit but eventually loses her when he is almost run over by a motorcyclist bombing through a labyrinth of snow and Titta angrily shouts, “you’ll make us all deaf, you idiots!”

elebrate. The snow increases over the next four days and the townspeople start to go out and shovel the roads. The Lawyer peers out from behind a snow bank and says to the audience, “This will go down as the Year of the Big Snow. With the exception of the Ice Age, it’s never snowed this heavily in our town.” He suddenly gets hit by a snow ball and says, “That must’ve been some young boy, not the usual guy. As I was saying, the exceptional years were 1541, 1694, 1728, 1888, when, against all odds, it snowed on July 13th,” as another snowball flies at him and he quickly flees. As Gradisca makes her way to church in the town square, Titta follows in hot pursuit but eventually loses her when he is almost run over by a motorcyclist bombing through a labyrinth of snow and Titta angrily shouts, “you’ll make us all deaf, you idiots!”

Near the end of the film, Titta’s mother is suddenly very sick and so Titta goes along with his father to comfort his ailing mother in the hospital and she tells him that it’s time he matured. When she asks Titta if he is still getting on his father’s nerves, Titta jokingly says, “He pounds me over the head! He’ll beat all the sense out of me!” Aurelio looks at his wife and son with warmth and admiration as he gently smiles adoring their alone time together. A friendly snow fight breaks out between Lallo, Gradisca, and the schoolboys but is quickly interrupted by a piercing bird call. Everyone suddenly stops and are mesmerized as a peacock, on the rim of a frozen fountain, shows off his magnificent tail and colors.

One morning Titta wakes to find his family in mourning and realizes his mother Miranda has died. Locking himself in his mother’s bedroom, he breaks down and cries. During the funeral Lallo faints and when they take Miranda away for burial everyone on the street who sees this follows to give their respect. After the funeral Titta walks out to the docks near the waters just as the puffballs return again drifting on the wind like in the beginning of the film.

In a deserted field with half the village present, Gradisca celebrates her marriage to a balding pot-bellied Fascist officer. The schoolboys chant a song for Gradisca saying, “Gradisca’s getting married and going away!” The kids then announce how they will miss her and be sad to see her go. A man raises his glass and exclaims, “She’s found her Gary Cooper! Though Gary Cooper’s a cowboy while Matteo is a carabiniere. But love is love all the same. Good luck, Gradisca.” They then get a group photo taking together and Gradisca starts to cry as she gets into the car with her new husband and leaves the town of Borgo but not before throwing out her wedding bouquet and shouting, “Good-bye! I love you all!” The last scene of the film is a child grabbing the bouquet while you hear Ovo say, “Where’s Titta? Titta’s gone away!” while the blind accordion is playing a tune as ‘manine’ puff balls float down from the sky starting another new year.

ANALYZE

Federico Fellini was born and brought up in Rimini, Italy, a small seaside town in the province of Emilia-Romagna. Amarcord is a neologism he contrived, which comes closest to the Emiliano-Romagnolo dialect phrase mi ricordo (I remember). Fellini, a great liar, denied this origin, claiming instead that it was a mysterious, cabalistic word, linked to invention rather than memory. Whatever the meaning, amarcord evokes another world: evanescent, unreal, unreachable, impalpable, like an image in the depth of a mirror that can be attested to for only a brief instant before it vanishes, like the images of the cinema.

Amarcord embodies this equivocation between memory and invention, between a world represented (remembered) and a world created (imagined). Amarcord is not memory—or if it is, it is false memory—not fragments of what once was but fragments of what is imagined to have been.

At times in Amarcord, the characters speak directly to a filmmaker (Fellini?), who appears to record the events and actions in the town. There is in the film, as in so many late Fellini works, the figure of a journalist-documentarian-archivist, who reports and comments on the happenings that are seen. But this is false, and rather than rendering the events as true, the device emphasizes their unreality and the artificiality of the representations. As the characters are exaggerated, so too is the documentary, and both become unreal.

All of Fellini’s films—from those up to La dolce vita (1960), which represent worlds (narrativized, realistic, dramatic), to those after La?dolce vita, including Amarcord (1973), which create worlds (dreamlike, episodic, artificial)—have a similar source in popular entertainments: the circus, with its clowns and unreality; variety theater, with its vulgarity and hyperbole, especially sexual; comic books, with their caricatures and sketchiness; silent film comedies, with their grace and innocence (Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy).

Amarcord is like a circus, composed of numbers, perfectly linear and sequential but whose links are neither logical, dramatic, nor narratively motivated. Each of the numbers in the film is a circus act, and the actors are the circus clowns. Indeed, there is no story in Amarcord, simply a collection of these episodes, whose order is only marginally consequential or where consequence is not of great importance: the seasons will change, Miranda will die, Gradisca will marry. Since the figures are essentially only images that have been designed, sketched, and exaggerated, rather than developed and given body to, they are simultaneously eternal and ephemeral, like the ocean liner Rex, which appears in its impossible magnificence out of the blackness of the sea at night, bringing Gradisca to tears and the others in boats to shouts of astonishment at the unreal wonder of it, in a kind of maritime séance. Even fascism is made into spectacle: were this a realistic film, fascism would be a politics that would eventually be overcome; in Amarcord, because fascism is only an act of clowns dressed up in a circus, it seems to be timeless, a perpetual provincialism and infantilism, more symbolic than historical or real, like Chaplin as the Great Dictator.

This is not what happens in Fellini’s I vitelloni (1953), the film apparently closest to Amarcord in its depiction of a small seaside town like Rimini. In I vitelloni, the town is in fact like Rimini, and the events that befall the characters elicit realistic tears, anguish, and anger; in Amarcord, to the contrary, the town is a caricature. It seems completely constructed, as false as the tears of Gradisca and as delusive as her dream marriage—and as contrived as the animal sexual hunger of Volpina (Foxy), the town nymphomaniac.

All the scenes in the film—Gradisca and the prince; Titta and the tobacconist; the harem episode at the Grand Hotel; Titta groping Gradisca in the cinema (“Are you looking for something?”); the celebration of the fascists; Uncle Teo up a tree, shouting for a woman; the dwarf nun who rescues him; the peeing in the classroom; even Aurelio forced to drink cod-liver oil—are less narrative events than tableaux, interesting chiefly not for what they represent but as comic performances of representing. No characters are characters in the usual sense, any more than the town is a real one. None have substance, none are palpable. It is an imaginary town with imaginary, projected characters who are fragments, magnifications, caricatures, and grotesques, as in a dream. The dwarf nun is no different in kind from the panting, openmouthed Volpina.

The characters in Fellini’s early films tend to be more realistic and individualized than those in his later ones, where circus elements are more evident and characters less natural, more fantastic and exaggerated. That is, whereas in The White Sheik (1952), Fernando Rivoli is both Rivoli and the clown he plays, in Amarcord, there are no such divisions. Rivoli dreams and Wanda dreams in The White Sheik, but in Amarcord, Gradisca is a dream, as are Uncle Teo and the whole of the film.

In Fellini’s Intervista (1987), his next-to-last film, he plays himself, a filmmaker shooting a film called Amerika, based on the novel by Kafka. In one scene, in his office at Cinecittà, he is interviewing a number of actors (all of whom are caricature “types”) for roles in his forthcoming film. Probably the scene is not unlike Fellini’s actual method of making a film. The first step for him was not the script or the story that the film would illustrate but rather faces and images that would evoke a world. Amarcord is exactly that, a “world,” part circus, part science fiction, composed of images of its inhabitants.

Fellini had a vast archive of photographs of actors, and out of these he would begin to construct his alternative universes and find his films—not representations of the world, not verisimilitude, but deformation and contrast, literally other worlds, elsewhere, beyond. And there was his sketching and doodling, essentially a playing, like his tours through the photographic archive of images of women with enormous breasts, ample bottoms (the stuff of dreams and masturbation); men grimacing pathetically, at once masking and revealing their impotence (the stuff of nightmares); dwarves, giants, the misshapen, the predatory.

There was no ready-made, no literary pretext for Fellini, but rather a search for the shape of the film in these images, a process of seeking out and discovery that carried over into the actual filming, where the film you see is the film being discovered in the process of filming, as if there were no “before” to it, as if the film had been found. It is not a record, then, of something outside it but an expression of an inspiration chanced upon at the moment of filming.

Fellini’s films (certainly his later ones, including Amarcord) bear the marks of their immediacy, sketchiness, momentariness, lack of finality, lack of development, inspirational and free associations (“You begin to shoot an action, and suddenly you are taken with the shimmering of light on a crystal of glass”). Such processes, essentially irrational, unconscious, almost impossible to plan (the vagaries of light, a sudden glimmer of recognition), were for Fellini (impressed by Jungian psychology and its notion of archetypes) signs of creativity and artistry. They were the I, the me, of Fellini.

In Amarcord, the Rex is made of cardboard, the sea of plastic, the sunset of paint. Very little is natural, and when it is, it is parodied and deformed. The natural was not an opportunity for Fellini, material to be recorded or rearranged, but rather a constraint, like rationality, defined order, and logic were—a limit on his creativity—and that is why the natural, the narrativized, and the realistic began to disappear from Fellini’s work, at first imperceptibly, before 1960, and then markedly afterward. The films increasingly became the expression of the soul of Fellini—not his autobiography, his life to be represented, but what he wished to express. “There is nothing autobiographical in Amarcord,” he said (nor is there in his celebrated essay “My Rimini,” which is neither autobiography nor exactly recollection but something rather more delicate and poetic: reminiscence). This expressive reality is made up of the spirits of Fellini, like those of Juliet in Juliet of the Spirits (1965). His films objectify these spirits and in so doing liberate them. The clowns of Amarcord are such spirits, not memories exactly but compressed symbols and associations, as in a dream.

One aspect of Amarcord that helps hold the film together and give it continuity is the change of seasons, from the initial appearance of the puffballs that herald the end of winter to their reappearance at the close of the film. An entire year goes by, and its four seasons come full circle. The seasonal changes have more to do with the material of the film, principally the light, than with what is represented: the darkness, shadows, and yellow effect of artificial lights in the winter; the glow of springtime, with its sharp, clear light, followed by summer haze; then the gray, foggy mistiness of autumn, when cows assume strange shapes; and finally, the glare of winter snow. Yellows, then, followed by greens, blues, whites, and all of these played off of by the whites and reds of the costuming, particularly of Gradisca, whose dress outlines her wiggling bottom.

Being freed from the constraints of narrative allows not only for a greater range of associations but for filmmaking in which images and sounds and their colors, textures, light, tones, rhythms, and movement can combine and resonate. And in Fellini’s case, these are resonances of joyfulness and generosity.

The beauty of film rests in the fragility of its images, a fragility often denied by narrative structures so tightly bound that images become firmly fixed in place. It is exactly in that place that Fellini’s films open up, and in doing so make images precious, alive, and transitory. The essential subject of Fellini’s films, and particularly of the late ones, like Amarcord, is the cinema itself, another world: ephemeral, touching, ineffable, comic, and grand . . . like a pheasant in the snow.

-Sam Rohdie

Amarcord is considered an exaggeration of Federico Fellini’s reality of his childhood mixed with fragments of what could be true and fragments that are only imagined to be true. “There’s nothing autobiographical in Amarcord,” Fellini had stated. Even the lawyer who is one of the main narrators in the film even admits to the audience that the stories he is giving us might not even be completely accurate especially coming from the character of Biscein, who he accuses of being a born liar and of making up a new story every single day. If the film Amarcord gives off an artificial like quality, it is never so obvious as it is in the scene with the arrival of the great liner Red which is clearly made of plastic and paint. When Rex passes all the townspeople out in their boats the look of the liner and the waves it is riding on look as fake and artificial as the town of Borgo and of its comic book like inhabitants; which in many ways suggests an illusion to reality. Even the sudden arrival of the fascist leaders seem like an absurd comic spectacle as you watch fascists marching down the streets looking like a bunch of clowns in one of Fellini’s circuses with a ridiculous looking papier-mâché Mussolini which looks more similar to a grotesque bulldog.

The film has several comic moments like the masturbation confession scene which isn’t really a confession at all, the school boys mutual masturbation session in which all four friends meet up and attend within a parked car, the several absurd dream sequences from several of the young characters and their fantasies concerning winning the hearts of their deepest loves. The hilarious dinner bickerings between Aurelio and Miranda and how Miranda is always one second away from killing Aurelio because of her husbands stupidity, the one afternoon release of mad uncle Teo who climbs a tree and is unwilling to come down continuously shouting “I want a woman!” like a lovesick animal; until he is eventually rescued by a nun who not only is a dwarf but when looking carefully also looks like a man. Biscein’s highly questionable story of him one evening making love to 28 virgins at the Sultan’s Harem. The humiliation of Titta when making a sexual advancement to Gradisca in the movie theatre and the buxom tobacconist and how she directs young Titta the right way to suck on a woman’s breasts. Gradisca seems to be the towns carnal fantasy, their symbol of hope, whom which has a great similarity to the angelic character of Claudia who is Marcello’s vision of purity in 8 ½

Like all great director’s Fellini is known to have signature styles in his movies which include dance sequences, religious guilt, sunrises or sunsets on the ocean and a circus like parade of performers played flawlessly by Nina Rota. Even though the themes in Fellini’s films stayed the same his style slowly changed throughout the years. His early work in I Vitelloni was more biographical and is the film that is apparently closest to Amarcord and of its portrayl of a small seaside town. I Vitelloni was also very different because it’s character’s were more grounded in reality unlike the world of Amarcord and I Vitelloni’s style was closer to the gritty Italian neo realism movement. After I Vitelloni Fellini followed that up later with La Strada, and Nights of Cabiria which still had an Italian Neorealism feel, but slight hints of Fellini’s later style was slowly creeping in. He slowly ventured off a little in his masterpiece La Dolce a Vita, and delved directly into surrealism with 8 ½ ; which developed into a style that critics refer to as ‘Felliniesque.’ After 8 ½ he did Juliet of the Spirits, Fellini Satyricon, and Fellini Casanova, and many people thought Fellini had lost it and gone off the deep end. And yet when he released Amarcord it was considered Fellini’s last perfect film and the end of his line of masterpieces. As funny as the story of Amarcord is, it perfectly balances itself out with several touching moments between its characters. What makes Amarcord such a magical and touching experience is it’s change of seasons similar to its change of emotions. Because the film spans itself for one full year the audience watches changes occur; good and bad. Miranda will die, Gradisca will marry and young Titta will be one more year wiser and mature. There are beautiful moments within the film like Borgo’s very first snowfall and how it gets plowed into a beautiful maze of snow and ice that separates Gradisca and the schoolboys. And of course the sudden notice of a peacock and of its color and beauty and of the spreading of its feathers within the snow is another magical moment by Fellini. The sad scenes in the film is the tragic death of Miranda, as you can finally see that the bickering between husband and wife was only just a slight fraction of their marriage and that each of them fulfilled a larger part of one another that we could never come to understand. Even Gradisca’s marriage is slightly depressing because even though she finally is getting a husband she’s always wished for, the husband is nothing like the Gary Cooper like man of her dreams; but instead an unattractive Fascist leader. Fellini always had a bitter-sweet affection for his character’s and of the fates that they eventually come to at the end of their journeys. Amarcord’s center is really about adolescence, the memories, lusts, desires, and mischievousness of a young Fellini in the childhood he himself wants to remember. Film critic Roger Ebert gave an excellent description of Federico Fellini and of the masterpieces he created stating, “Fellini was more in love with breasts than Russ Meyer, more wracked with guilt than Ingmar Bergman, more of a flamboyant showman than Busby Berkeley. He danced so instinctively to his inner rhythms that he didn’t even realize he was a stylistic original; did he ever devote a moment’s organized thought to the style that became known as “Felliniesque,” or was he simply following the melody that always played when he was working?”

Like all great director’s Fellini is known to have signature styles in his movies which include dance sequences, religious guilt, sunrises or sunsets on the ocean and a circus like parade of performers played flawlessly by Nina Rota. Even though the themes in Fellini’s films stayed the same his style slowly changed throughout the years. His early work in I Vitelloni was more biographical and is the film that is apparently closest to Amarcord and of its portrayl of a small seaside town. I Vitelloni was also very different because it’s character’s were more grounded in reality unlike the world of Amarcord and I Vitelloni’s style was closer to the gritty Italian neo realism movement. After I Vitelloni Fellini followed that up later with La Strada, and Nights of Cabiria which still had an Italian Neorealism feel, but slight hints of Fellini’s later style was slowly creeping in. He slowly ventured off a little in his masterpiece La Dolce a Vita, and delved directly into surrealism with 8 ½ ; which developed into a style that critics refer to as ‘Felliniesque.’ After 8 ½ he did Juliet of the Spirits, Fellini Satyricon, and Fellini Casanova, and many people thought Fellini had lost it and gone off the deep end. And yet when he released Amarcord it was considered Fellini’s last perfect film and the end of his line of masterpieces. As funny as the story of Amarcord is, it perfectly balances itself out with several touching moments between its characters. What makes Amarcord such a magical and touching experience is it’s change of seasons similar to its change of emotions. Because the film spans itself for one full year the audience watches changes occur; good and bad. Miranda will die, Gradisca will marry and young Titta will be one more year wiser and mature. There are beautiful moments within the film like Borgo’s very first snowfall and how it gets plowed into a beautiful maze of snow and ice that separates Gradisca and the schoolboys. And of course the sudden notice of a peacock and of its color and beauty and of the spreading of its feathers within the snow is another magical moment by Fellini. The sad scenes in the film is the tragic death of Miranda, as you can finally see that the bickering between husband and wife was only just a slight fraction of their marriage and that each of them fulfilled a larger part of one another that we could never come to understand. Even Gradisca’s marriage is slightly depressing because even though she finally is getting a husband she’s always wished for, the husband is nothing like the Gary Cooper like man of her dreams; but instead an unattractive Fascist leader. Fellini always had a bitter-sweet affection for his character’s and of the fates that they eventually come to at the end of their journeys. Amarcord’s center is really about adolescence, the memories, lusts, desires, and mischievousness of a young Fellini in the childhood he himself wants to remember. Film critic Roger Ebert gave an excellent description of Federico Fellini and of the masterpieces he created stating, “Fellini was more in love with breasts than Russ Meyer, more wracked with guilt than Ingmar Bergman, more of a flamboyant showman than Busby Berkeley. He danced so instinctively to his inner rhythms that he didn’t even realize he was a stylistic original; did he ever devote a moment’s organized thought to the style that became known as “Felliniesque,” or was he simply following the melody that always played when he was working?”