A Man Escaped (1956)

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”A Man Escaped Robert Bresson” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped is generally looked at as one of the greatest prison-break movies ever made. The story was inspired by Andre Devigny, a decorated French lieutenant in World War II who escaped from Fort Montlue prison in German-occupied Lyon in 1943. Besides the beginning and final shots of the film, the entire story is set within the interior walls of the prison, which was modeled identically on the original. Bresson has the main protagonist Fontaine prepare for what everyone tells him will be an impossible escape, as he confronts moments of certain despair ultimately learning to prevail in the end. French director Robert Bresson who had also suffered cruelty at the hands of Germans during the war, wrote the screenplay and dialogue for the film which is based on a journalistic account Devigny had published in 1954. By the time Bresson made this film, he was labeled as a religious director, as Fontaine in A Man Escaped is a soldier and a man of action, but, like his predecessors, he also is a strong spiritual force, inspiring hope in his fellow prisoners. Bresson reveals the story of A Man Escaped in an unadorned style, completely devoid of special effects, dramatic thrills, elevated tension, and the use of known movie stars. Most filmmakers use those tools as an artistic way to manipulate and distract its audience, Bresson only uses the bare necessities that are needed to tell its story, and the audience can fill the rest in for themselves. Much has been discussed on Bresson’s ‘actor-model’ technique, which remains for many an obstacle when approaching and enjoying his films. Bresson believed that actors were ‘alien’ to the medium of film, because the camera could detect the slightest sign of artificiality and calculation. He did not want any facial expressions, physical gestures, and vocal inflections to come out of any of the performances, believing any slight form of eccentricity was unnecessary. He wanted the actor to simply embody the character, perform the physical actions as needed, look plausible when doing it, and try to not draw any undue attention from themselves. And so A Man Escaped creates character not through the actor’s performance but through the actions that are performed, as action becomes the character. [fsbProduct product_id=’728′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Fontaine’s acting method is similar to Bresson’s directing method, in which it involves the close scrutiny of salient details, whether it’s sitting in solitary confinement most of the day, tapping out messages in a code, standing on a shelf to look out a high barred window, watching food plates enter and leave, staring out at guards through a peep hole or secretly exchanging notes during washing-up. Bresson stages each scene without the use of fancy cinematography, using the basic vocabulary of close, medium, and long shots to tell what needs to be told about every scene, while simultaneously keeping the audience absorbed every step of the way. We watch in awe as Fontaine methodically and rhythmically takes apart his cell door, a window frame, his bedsprings, and patiently winds his bedclothes into rope, as we perceive these very acts as a form of attentiveness, creativity, diligence, fortitude, skill, patience, persistence and, not least, faith.

[phpbaysidebar keywords=”A Man Escaped Robert Bresson” num=”20″ customid=”ClassicArtFilms” country=”1″ sortorder=”EndTimeSoonest” listingtype=”All” minprice=”15″]Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped is generally looked at as one of the greatest prison-break movies ever made. The story was inspired by Andre Devigny, a decorated French lieutenant in World War II who escaped from Fort Montlue prison in German-occupied Lyon in 1943. Besides the beginning and final shots of the film, the entire story is set within the interior walls of the prison, which was modeled identically on the original. Bresson has the main protagonist Fontaine prepare for what everyone tells him will be an impossible escape, as he confronts moments of certain despair ultimately learning to prevail in the end. French director Robert Bresson who had also suffered cruelty at the hands of Germans during the war, wrote the screenplay and dialogue for the film which is based on a journalistic account Devigny had published in 1954. By the time Bresson made this film, he was labeled as a religious director, as Fontaine in A Man Escaped is a soldier and a man of action, but, like his predecessors, he also is a strong spiritual force, inspiring hope in his fellow prisoners. Bresson reveals the story of A Man Escaped in an unadorned style, completely devoid of special effects, dramatic thrills, elevated tension, and the use of known movie stars. Most filmmakers use those tools as an artistic way to manipulate and distract its audience, Bresson only uses the bare necessities that are needed to tell its story, and the audience can fill the rest in for themselves. Much has been discussed on Bresson’s ‘actor-model’ technique, which remains for many an obstacle when approaching and enjoying his films. Bresson believed that actors were ‘alien’ to the medium of film, because the camera could detect the slightest sign of artificiality and calculation. He did not want any facial expressions, physical gestures, and vocal inflections to come out of any of the performances, believing any slight form of eccentricity was unnecessary. He wanted the actor to simply embody the character, perform the physical actions as needed, look plausible when doing it, and try to not draw any undue attention from themselves. And so A Man Escaped creates character not through the actor’s performance but through the actions that are performed, as action becomes the character. [fsbProduct product_id=’728′ size=’200′ align=’right’]Fontaine’s acting method is similar to Bresson’s directing method, in which it involves the close scrutiny of salient details, whether it’s sitting in solitary confinement most of the day, tapping out messages in a code, standing on a shelf to look out a high barred window, watching food plates enter and leave, staring out at guards through a peep hole or secretly exchanging notes during washing-up. Bresson stages each scene without the use of fancy cinematography, using the basic vocabulary of close, medium, and long shots to tell what needs to be told about every scene, while simultaneously keeping the audience absorbed every step of the way. We watch in awe as Fontaine methodically and rhythmically takes apart his cell door, a window frame, his bedsprings, and patiently winds his bedclothes into rope, as we perceive these very acts as a form of attentiveness, creativity, diligence, fortitude, skill, patience, persistence and, not least, faith.

PLOT/NOTES

(The following is a true story. I present it as it happened without adornment.)

After the establishing shot of Montluc prison, but before the opening credits, the camera rests on a plaque commemorating the 7,000 men who died there at the hands of the Nazis.

Arrested but not handcuffed, Fontaine (François Leterrier), a member of the French Resistance, is being driven to prison with two other members of the resistance. Though he maintains a relatively neutral expression, his off-screen glances of the vehicle door and of his left hand testing the door handle, gives him an opportunity to escape his Nazi captors when the car carrying him is forced to stop. But he is soon apprehended, beaten for his attempt, handcuffed and taken to the jail.

After the beating the Nazi guards drag and place an unconscious Fontaine into his cell.

“I could feel I was being watched. I didn’t budge. Nothing broken but I probably wasn’t a pretty sight. I wiped myself off best I could. The charges against me were so severe and I’d aggravated them so clearly. Why haven’t they shot me?”

“While waiting in the courtyard I’d gotten used to the idea of death. I would have preferred an immediate execution. They beat me back with feet and fists and I found myself alone. My cell was hardly nine by nine feet by six feet. The furnishings were rudimentary. A wood frame supporting the mattress and two blankets.”

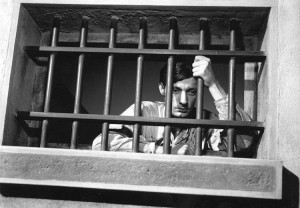

In a recess near the door was a slop pail. Finally, fixed to the wall was a stone shelf. I managed to climb onto this shelf to reach the window. In the small courtyard that extended before me three comfortable dressed and clean-shaven men were walking apparently without supervision.”

One of the men named Terry speaks out to Fontaine and throw up a safety-pin which will give him the ability to unlock his handcuffs. This turns out to be pointless because, in reassigning him to a cell on the top floor, the guards remove his handcuffs anyway.

“Soon, I’d managed to communicate with my neighbor. A young worker at a bronze foundry, he had killed a German soldier during a quarrel. He was to be executed any day. He was 19.”

Fontaine writes a letter to his loved ones and risks giving the letter to Terry, using the use of a string, a handkerchief and a sack through his window.

“To reassure my family and give them a hope I did not possess. Yes, and especially to warn my superiors that the post transmitter I was in charge of was aiding the German’s they’d cracked the code. I was determined to run the risk. And what a risk. Trusting my letters to a stranger could mean the end for me as well as the recipients. We could also be seen in the courtyard or interrupted at any moment.”

Fontaine asks Terry for a safety-pin and he quickly returns one to him. “On the paper written in a feminine hand, was the word ‘courage.’ There was also a safety-pin. My neighbor had taught me the method. But it didn’t work right away and I hardly believed it would.” Instructions are written on the wall as Fontaine breaks out of his cuffs and could finally realize his still arms and wrists, feeling a sudden sense of victory.

Terry quickly tells Fontaine, “Your letters went out yesterday. They should have arrived by now.”

“My visits to the window grew longer and longer. I could see the courtyard, the walls and the infirmary yard. I unconsciously prepared myself. I knew they conducted executions within the prison compound. A crazy thought crossed my mind.”

“I stayed up into the night teaching him the Bataillonaie’s march he’d asked for. What does it matter? Who cares? All young guys who never had much luck. It was the only help I could give him.”

A guard retrieves Fontaine and takes him up stairs to another cell. “I had left the ground floor for good. I was now in cell 107 on the top floor.” While out for water Fontaine observes the surroundings thinking, “I tried to read on their faces what kind of men they might be. I also studied the walls. With nothing to do, no news and in terrible solitude, we were 100 unfortunates awaiting for fate. I had no illusions about my own. If could only escape, run away. It was chance or idleness that gave me my first break. I often sat across from my door with nothing better to do than let my gaze wander. It was made of two panels of six oak boards held within a frame of the same thickness. In the gap between two boards, I saw that the joining wood was not oak, but wood of another color, beech or poplar. There would surely be a way to take the door apart. To get an iron spoon, tin or aluminum being to soft or brittle I had to wait through several meals.”

Fontaine communicates with his new neighbor, unknowingly interrupting, at that very moment, his neighbors suicide attempt.

“I made a kind of chisel from it. No, the boards weren’t joined by mortise and tenon joints carved into the oak itself, but by strips of soft wood my tool could easily tackle. I estimated that it would take four or five days to make it through a strip by cutting or chipping the wood. But every evening at the same time, I also had to get some air. Progress was slow due to my fear of making noise and the constant threat of being taken by surprise. Moreover, I had to keep brushing under the doorway with a bit of straw torn from the cell broom.”

Suddenly one evening Terry calls out to Fontaine. He tells him he is being taking away, lord knows where. “How he could evade surveillance and come to my door, I’d never know.” Francois asks about his neighbor and he is told he was executed the day before yesterday. “Terry’s departure and the death of a comrade I had never seen left me in distress. Nevertheless, I carried on with my work. It prevented me from thinking. The door just had to open. I had no plans for afterwards. ”

“A new arrival, the Pastor de Leyris would earn my trust, fulfill my need for companionship.” The Pastor talks about need the bible to read to keep things busy, while Francois states that he does things to keep things busy as well. Fontaine also meets Orsini in the local washroom, which becomes the meeting place for them to exchange notes.

“Three boards should make a big enough opening. Across from me in 108 someone kept lookout, which made my work much easier. On the other hand my neighbor’s silence troubled me. I knew he was there. I was sure of it. My neighbor worried me so much I no longer dared touched my door. I settled for plugging the holes with paper I blackened on the ground.”

Fontaine gets to finally know his neighbor who named is Mr. Blanchet after he accidently falls out in the courtyard. Blanchet tells Fontaine to stop carving or Fontaine will get the whole floor punished. “After three weeks of effort making as little noise as possible, I’d managed to separate three boards along the sides. But they were held in the frame at the top and the bottom by joints which bent the handle of my spoon. To break apart the edge of the frame, I’d need to find another spoon. Only then would I have enough leverage.”

The Pastor de Leyris has miraculously lucky to have gotten a bible, and so is Fontaine who has luckily found another spoon. After using both spoons on the door, the frame suddenly broke, but over a bigger area than he’d attended. “I was able to put the pieces back in place and make them stick.” Fontaine comforts Blanchet and when Blanchet asks ‘why bother?’ in living Fontaine says, “To fight. To fight the walls, to fight myself, to fight the door. You , too, Mr. Blanchet, should fight and hope. To go home, to be free.” Francois says he has no friends or family and no hope. Fontaine says, “I think of you, Mr. Blanchet, and it gives me courage.” Blanchet says, “For me, real courage would be to fill me. I tried. I made a noose with my laces. The nail broke. I heard taping on the wall.” Fontaine tells him that was him that was tapping on to the wall.

“I was afraid they would open or close my door forcefully. Fortunately it was up to me to handle it. A month of patient work and the door was open. It took a lot of time to put it back in place and camouflage it. Inside the building, no patrols, no guards. Getting into the hallway wasn’t that big of a deal. But I also had a goal. ” Fontaine let Blanchette know it is cell 107 and that if he can he will return tomorrow. “His surprise pleased me. That night I went to sleep less miserable. “The head guard and the sergeant slept on the second floor. The corporal slept on the ground floor near the door to which he had the key. The door remained locked throughout the night. I visualized every possibility and even what was impossible. I devised a thousand plans, but acted on none.”

The Pastor asks Fontaine’s if he reads the bible and Fontaine tells him sometimes when things get bad. Blanchet believes Fontaine won’t get through. Fontaine tries to escape by 10:00 but certain of disaster backs down. In the public wash room Orsini gives Fontaine the exit route from the building and how to dismantle his door. “Read it carefully and tear it up. You can count on me, but I’m not the ‘bravest man alive,”

“40 feet of rope strong enough to hold a man is what I needed. The netting from the bed frame supplied about 120 feet of flexible and sturdy wire. I made my first segment of rope with materials from my pillow. The little horsehair it contained went into the mattress. I folded the fabric I obtained in quarters turning the edges inward to prevent fraying. I twisted it tightly. By wrapping a wire in the opposite direction I was able to maintain the tension.”

Orsini tells Francois that he will try his door again, and by tom he will let him know if they will split up or stick together. Orsini believes their plan is too long and complicated and he actually has another way. “During the walk with two ropes and two hooks. On the roof of the bathroom, He climbs the drain pipe and stays hidden.”

Fontaine doesn’t believe Orsini’s plan is very good, and the next day the Nazi guards took Orsini in for interrogation. “I was so closely watched we lost contact. What was he doing? I couldn’t make sense of it”

That evening Orsini makes an attempt to escape, but fails to get very far because his rope broke at the second wall. Orsini is tossed back in his cell and beaten up by the guards, and is to be executed within a few days. The preacher tells Fontaine not to blame himself about Orsini, because he couldn’t wait any longer for hope of a new life. The pastor says, “Perhaps that’s what Christ meant. I copied out the passage for you. These are his words to Nicodemus” He reads the passage out-loud for Blanchet to hear: “Nicodemus said unto him, ‘How can a man be born when he is old?’ Jesus answered, ‘Do not marvel that I said to you, ‘You must be born again.’ The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but cannot tell where it comes from and where it goes.”

Suddenly Fontaine hears the gunshots that kill Orsini. “The terrace of our building as well as the compound walls must have the same ledge. I had to wait. I was close to my goal, and the smallest error could prove fatal. I knew it was dangerous to descend into the walkway and climb the second wall. My strength had diminished. I run a line between the two walls and I cross over like a monkey hanging by my hands and feet. I made the third hook with the two shortest bars. It was every bit as sturdy and functional as the others. Still using the wire, I fashioned three loops which I attached to the foot of each hook. My tests showed that strong leverage would not damage the hoods or the loops.

The prisoners are told that the guards will be searching cells for pencils. One day Francis receives a packet of clothes from his mother. “I made braids just like I’d seen my mother make with my sister’s hair. Nothing was spared except for one handkerchief. With the string, I made the connections. I would throw this rope from the compound wall to the exterior wall. It had to be supple and consistent. The wire wasn’t suitable. Besides, I had exhausted my supply. With the blanket Blanchet gave me, I had enough to finish the other rope. We only went out now in small groups of about 15. The prison was filling up. It wasn’t uncommon to see two prisoners per cell. Others appeared and disappeared like ghosts. I even saw one of them dressed for a wedding.”

The other prisoners grow somewhat skeptical of Fontaine’s escape plans, saying he is taking too long. Fontaine is taken to headquarters and is charged with espionage and planning a bomb attack which is punishable by death. He is sentenced to be executed by firing squad. Fontaine is taken back to jail and put back in the same cell. “I broke nervous laughter that relieved me. Then, a bit later, I once again feared that all my efforts would be for nothing.”

Fontaine gets a cellmate, François Jost (Charles Le Clainche), a sixteen-year-old young man who had joined the German army. “Dressed half as French soldier, half as German soldier, he was disgustingly filthy. He seemed barely 16. Is he a stool pigeon? Did they think I’d talk shaken up by my verdict?” Fontaine is not sure whether he can trust Jost (whom he sees speaking on friendly terms with a Nazi guard) and realizes he’ll either have to kill him in cold blood or take him with him in the escape.

After Jost admits he too wants to escape, Fontaine chooses to trust the boy and tells him the plan saying, “Ive thought it all through, calculated everything. From getting out of the building to crossing over the walkway. There are still unforeseen factors. We might have surprises. I say ‘we’ because now…And believe me, Jost, all the odds are in my favor. I’m absolutely sure of the tools I’ve made, sure of myself, sure of my luck and yours. Once we’re out, I’ll take care of you. I’ll help you make the most of your freedom, I swear.”

“I emptied my mattress into Jost’s and cut the cloth following the markings. In less than two hours, the rope was ready and tested, the cell was organized and swept.” Francois says goodbye to his friend Blanchet. “We had made four bundles. One with our shoes tied together, another with our jackets, a third with the big rope and its hooks and the fourth with the softer rope for the walkway.

One night, Fontaine and Jost escape by gaining access to the roof of the building, There is one guard with a tommiegun, but Jost can’t kill him. Francois decides to take the job and climb the rope down to the courtyard. Jost can’t do it and so Fontaine kills the Nazi guard with a Tommie-gun. He slowly sneaks behind the guard. “I let go of the iron hook. It didn’t seem a sure weapon. I had to act but couldn’t. With both hands I restrained the beating of my heart. Was he sitting down? Was he lighting a cigarette? He wasn’t coming any closer to me. He was right there, very close, about a meter away from me. He made a half-turn. Fontaine kills the guard off-screen and signals Jost to climb down. gun, climbing the wall and then roping to an adjacent building.

“He’d forgotten our jackets and shoes on the roof, but I didn’t say a thing. Alone, I might have remained there. All I knew about the guard system is that there was a sentry booth positioned at each corner. Was it occupied or not? It wasn’t. Cut the electrical wire.”

The two climb the wall and then rope to an adjacent building. “If only my mother could see me,” Jose says. They two walk away from the prison undetected, and now free.

ANALYZE

Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956) is generally considered one of the greatest prison-break movies ever made. It was inspired by the story of André Devigny, a decorated French lieutenant in World War II who escaped from Fort Montluc prison in German-occupied Lyon in 1943 and was awarded the Cross of the Liberation by Charles de Gaulle after the war. Except for the opening scene and the final shots, the entire film is set in the interiors and exteriors of a prison, modeled on the original, and follows the detailed activities of Fontaine (François Leterrier), the protagonist, as he prepares for what everyone tells him is an impossible feat. Bresson, having himself suffered cruelty and internment at the hands of the Germans during the war, wrote the screenplay and dialogue, based on a journalistic account Devigny had published in 1954 as “The Lessons of Strength: A Man Condemned to Death Has Escaped” (his memoir A Condemned Prisoner Has Escaped was published in 1956). Although the film’s preface assures us that it does not embellish that account, and Devigny himself acted as Bresson’s factual adviser, there are critical differences between his work and Bresson’s film. In fact, the first title Bresson considered, Aide-toi . . .—part of a phrase meaning “Heaven helps those who help themselves”—suggests that he was as attracted to the spiritual significance of the story as he was to Devigny’s scrupulous description of his experience. The film’s brilliant exposition of Fontaine’s daily efforts to convert the objects in his cell into the instruments of escape indeed became for Bresson the expressive means for the man’s pragmatic form of faith.

By the time he made this film, Bresson had been labeled a religious director; his first feature, Les anges du péché (The Angels of Sin, 1943), set in a convent, concerned the fervent endeavors of a devout novice to transform the life of a murderess, and Diary of a Country Priest (1951), the film preceding A Man Escaped, was the chronicle of a saintly vicar struggling against the indifference and iniquities of his first parishioners. The protagonist of A Man Escaped is a soldier and a man of action, but, like his predecessors, he is also a spiritual force, inspiring hope in his fellow prisoners. This is epitomized when, to determine whether the adjacent cell is occupied, Fontaine taps on the wall, effectively interrupting, at that very moment, his neighbor’s suicide attempt. Later, this prisoner—Blanchet (Maurice Beerblock)—buoyed by Fontaine’s courage and resolve, contributes a blanket to allow Fontaine to complete the final ropes needed for his mission.

Perhaps to avoid compromising this noble image of his hero, Bresson ends the film on an uplifting note, as Fontaine and Jost (Charles Le Clainche), his late-arriving cell mate, walk off to freedom to the chorus of the Kyrie from Mozart’s C-minor Mass. In reality, Devigny and his cell mate were recaptured, and the former, suspecting betrayal, abandoned his comrade. Also, whereas Devigny was a family man, we learn little of Fontaine’s outside relations. Even the specific crime of which he is accused is revealed only late in the film, and is identified as treason, whereas the immediate cause of Devigny’s arrest was his murder of the commandant of the Italian police. Clearly, Bresson was more interested in the inspirational nature of the story than in adhering to every historical fact.

The story and action of A Man Escaped also gave Bresson the opportunity to advance his own emerging aesthetic. Impressed by what he called Devigny’s “straightforward, very precise, technical account of the escape . . . written in an extremely reserved, very cool tone,” Bresson sought an approach that served those qualities, privileging the physical aspects and details of Fontaine’s endeavor and avoiding exaggeration, melodrama, and sentimentality. Even the protagonist’s narrative voice-over, based on Devigny’s text, keeps to the facts and is delivered in a neutral, uninflected tone. These voice-overs are accompanied by shots of Fontaine that betray a slight smile or a twinkling of the eye, complementing the content and tenor of what is said, without recourse to the emotional redundancies that a typical “performance” would add. Through a documentary-like stress on the action, process, and overall ambience of his material, Bresson clarified his pursuit of a more economic, streamlined film aesthetic, peeling away what he believed were the excesses of conventional narrative cinema. Already in Diary of a Country Priest, he had begun this, by using fewer professional actors (and the protagonist was played by a relative amateur) and making efficient and poetic use of offscreen space. In A Man Escaped, virtually every “actor” is a nonprofessional, including Letterier, who was a philosophy student at the Sorbonne at the time.

The story and action of A Man Escaped also gave Bresson the opportunity to advance his own emerging aesthetic. Impressed by what he called Devigny’s “straightforward, very precise, technical account of the escape . . . written in an extremely reserved, very cool tone,” Bresson sought an approach that served those qualities, privileging the physical aspects and details of Fontaine’s endeavor and avoiding exaggeration, melodrama, and sentimentality. Even the protagonist’s narrative voice-over, based on Devigny’s text, keeps to the facts and is delivered in a neutral, uninflected tone. These voice-overs are accompanied by shots of Fontaine that betray a slight smile or a twinkling of the eye, complementing the content and tenor of what is said, without recourse to the emotional redundancies that a typical “performance” would add. Through a documentary-like stress on the action, process, and overall ambience of his material, Bresson clarified his pursuit of a more economic, streamlined film aesthetic, peeling away what he believed were the excesses of conventional narrative cinema. Already in Diary of a Country Priest, he had begun this, by using fewer professional actors (and the protagonist was played by a relative amateur) and making efficient and poetic use of offscreen space. In A Man Escaped, virtually every “actor” is a nonprofessional, including Letterier, who was a philosophy student at the Sorbonne at the time.

Much has been written about Bresson’s rejection of actors, which remains, for many, an obstacle to enjoying his films. Far from a directorial quirk, however, this decision was consistent with his aim of creating a uniquely cinematographic narrative form, one less dependent on psychologically motivated acting and dramatically structured scenes. He believed that actors—indeed, acting itself—were alien to the medium of film, because the camera could detect the slightest sign of artificiality and calculation. This conviction not only proscribed the use of professional actors given to a familiar repertoire of facial expressions, physical gestures, and vocal inflections, it also ruled out the kind of nonprofessionals found, for example, in Italian neorealist films—very popular at the time—who were encouraged to exude emotions and sentiments in order to move the viewer.

Bresson’s refusal to accede to a cinema dominated by the actor affected the overall look, structure, and impact of his films. Rather than grounding them in performances and dramatic scenes—the prevailing method of most narrative films even today—he shifted the emphasis to the inherent aspects of the medium: the framing, duration, and editing of shots, and the use of sound and offscreen space. These were the features that determined the rhythm of a film’s movement toward its goal. In other words, for Bresson, the word performance did not refer to something that actors did but something the entire organic structure of a film did. In referring to his métier, therefore, he chose the word cinematography over cinema, because the latter was associated with the more traditional form of dramatic filmmaking.

This does not mean that Bresson was indifferent to his characters or the people who “played” them. It is more a matter of how he chose the latter. He sought people for their transparent innocence, their virginal presence before the camera, and the unstudied nature of their physical gestures. These qualities rendered them as pliable as framing, lighting, and camera angles. As such, they were not actors at all, said Bresson, but “models,” whose faces, hands, voices, and body language could be carefully fashioned, molded to fit the contours and audiovisual dynamic structure of each film.

A good example in A Man Escaped of how the model is incorporated within Bresson’s cinematographic ensemble is the opening sequence. Through framing and editing, we are introduced to the protagonist, who, having been arrested by the Gestapo, is being driven to prison with two other members of the Resistance. Though he maintains a relatively neutral expression, his actions and offscreen glances tell the story. As he awaits the right moment to make a run for it, the camera pans down from his face to his left hand, which is testing the door handle. The crosscutting between his face and the road ahead testifies to his ongoing assessment of the situation. Without the benefit of traditional acting, dialogue, or voice-over, we enter directly into the mind-set of the character and the style that will dominate the rest of the film.

This approach, powerfully realized throughout A Man Escaped, was further refined in Pickpocket (1959) and The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), introducing an altogether new kind of narrative filmmaking, one that many considered austere. Though the technical features of this style, which was soon labeled “Bressonian,” were adopted by many European filmmakers in subsequent decades, the unmistakably personal and unique aspect of it has often been misunderstood. The economy, purity, and rigor of Bresson’s aesthetic are directly related to his vision of the world, a complex perspective that carefully balances a belief in free will against the notion of preexistent design. For example, while A Man Escaped seems to be clearly mobilized by the protagonist’s will to be free, at the same time, Bresson said his aim was to “show the miracle [of] an invisible hand over the prison, directing what happens.” Thus, the propulsive trajectory of Bresson’s narratives—a result of the removal of excess and the refinement of technique—serves his overriding theme that human lives follow an implacable course. This is also apparent in such later masterpieces as Au hasard Balthazar (1966), Mouchette (1967), Lancelot of the Lake (1974), and L’argent (1983), despite their widely different subjects and increasingly cynical view of a world in which spiritual redemption seems to have vanished.

As the opening sequence of A Man Escaped suggests, and as the remainder of the film confirms, Bresson’s method of creating character was not through the actor’s performance but through the actions performed—an approach that emphasized the external world and concrete reality. It is what a fictional figure does that creates character; his inner self is revealed by his outward actions and how he performs them. In short, action is character. As we watch Fontaine go about his routines, methodically taking apart his cell door, a window frame, or his bedsprings, patiently winding his bedclothes into ropes, we perceive in these very acts the qualities that inspire others: attentiveness, creativity, diligence, fortitude, skill, patience, persistence, and, not least, faith. It follows that these actions are not rendered passively. For example, by employing the shot–counter shot rhythm generally used for conversations, Bresson converts Fontaine’s interactions with his cell door into a struggle between protagonist and antagonist.

From the moment we perceive Fontaine’s intent in the opening sequence, we are gripped by all that he does, forced to become as attuned to his environment as he is, sensitive to every offscreen sound and unseen threat. This intense involvement on the part of the viewer—clearly the reason the film works so well as a suspenseful prison drama—can be attributed to Bresson’s respect for the limitations of the narrative first person. He had already experimented with this point of view in Diary of a Country Priest, but here he reinforces the first-person perspective by harnessing and sharpening those filmic elements directly relevant to it. And so, since the protagonist’s perspective is restricted by the spatial conditions of his imprisonment, the film, too, observes these boundaries. As a result, sound and offscreen space are heavily accented, for the simple reason that Fontaine must strive to become more sensitive to these phenomena as indicators of what is happening outside his cell. As he works to dismantle the cell door, he listens for any sign of an approaching guard. Whether to document Fontaine’s frustrated but affecting communication with the prisoners in adjacent cells or to establish his awareness of life outside the prison walls, sounds and unseen spaces assume a vivid reality every bit as palpable as what we see on the screen.

It is through this masterful use of all facets of the medium that Bresson created not only one of the most exciting movies about imprisonment and the urge toward freedom but also one of the greatest, most purely filmic experiences any director has achieved.

-Tony Pipolo

Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped is generally considered one of the greatest prison-break movies ever made. It was inspired by the story of Andre Devigny, a decorated French lieutenant in World War II who escaped from Fort Montluc prison in German-occupied Lyon in 1943 and was awarded the Cross of the Liberation by Charles de Gaulle after the war. Except for the beginning and final shots of the story, the entire film is set within the interiors and exteriors of the prison, modeled on the original. The characters within most Bresson films are people who are confronted with certain despair, and how they try to prevail in the face of unbearable circumstances. The audience follows the protagonist as he prepares for what everyone around him says is an impossible feat. Bresson had himself suffered essence cruelty and internment at the hands of the German’s during the war, and wrote the screenplay and dialogue for the film, which was based on a journalistic account Devigny had published in 1954 as “The Lessons of Strength: A Man Condemned to Death Has Escaped”. Even though the film’s preface assures the audience that it doesn’t embellish that account, Devigny himself acted as Bresson’s factual adviser, as the film brilliantly creates the exposition of Fontaine’s daily efforts to convert the objects in his cell into the instruments of escape, becoming the expressive means for the man’s pragmatic form of faith.

Some feel that Bresson’s Catholic upbringing and belief system is behind the thematic structure of most of his films, similar to Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky and Carl Dreyer. Robert Bresson’s other masterpieces are Au Hasard Balthazar which tells the tragic story about a young farmers daughter, and a donkey passed from cruel master to cruel master and in which both of their fates parallel one another. Au Hasard Balthazar is one of the most spiritual films I have ever witnessed and is on my top ten films of all time. Pickpocket is about an isolated man who is a professional pickpocket thief, Diary of a Country Priest told the story of a young Priest having to deal with the guilt of judging others and himself being judged in a small town, Mouchette is about a young girl and her struggles with adolescent life which is very similar to Marie’s character in this film and can be considered a sort of companion piece, and his final masterpiece L’ argent, is a story about the evils of money and greed.

By the time Bresson made A Man Escaped he was already labeled a religious director. Fontaine is a soldier and a man of action, but, like his predecessors, he is also a spiritual force, inspiring hope in his fellow prisoners. This is epitomized when, to determine whether the cell next to him is occupied, Fontaine taps on the wall, effectively interrupting, at that very moment his neighbor’s suicide attempt. Later, the same prisoner Blanchet, buoyed by Fontaine’s courage and resolve, contributes a blanket to allow Fontaine to complete the final ropes that are needed for his escape. Perhaps to avoid compromising this noble image of his hero, Bresson ends the film on an uplifting note, as Fontaine and Jost walk off to freedom to the chorus of the Kyrie from Mozart’s C-minor Mass. In the original historyDevigny and his cell mate were recaptured, and the former, suspecting betrayal, abandoned his comrade. Also, whereas Devigny was a family man, we learn little of Fontaine’s outside relations. Even the specific crime of treason that Fontaine is accused of later in the film, is completely different of Devigny’s, whose immediate arrest was for the murder of a commandant of the Italian police. Clearly, Bresson was more interested in the inspirational significant nature of the story rather than the bleak historical fact of it. Most of Bresson’s later films will keep the same themes of spiritual significance of A Man Escaped, but will end on a much less optimistic note, as Bresson’s worldview of people and society will manifest into something much harsher and crueler.

A Man Escaped and its story gave Bresson the perfect opportunity to advance his own emerging aesthetic. Impressed by what Bresson called Devigny’s “Straightforward, very precise, technical account of the escape…written in an extremely reserved, very cool tone,’ Bresson sought an approach that served those qualities, privileging the physical aspects and details of Fontaine’s endeavor and avoiding exaggeration, melodrama, and sentimentality. Even the protagonist’s voice-over, which is based on Devigny’s text, keeps to the facts and is delivered in a neutral, uninflected tone. These voice-overs are accompanied by shots of Fontaine that betray a slight smile or a twinkling of the eye, without recourcing to the emotional redundancies that a typical performance would add. Already in Diary of a Country Priest, Bresson had begun this, by using fewer professional actors (and the protagonist was played by a relative amateur) and making efficient and poetic use of off-screen space. In A Man Escaped, virtually every actor is a nonprofessional, including Letterier, who was a philosophy student at the Sorbonne at the time.

Bresson’s spiritual purpose in most of his films is that he has the audience go to the character’s and learn to inhabit them, instead of passively letting them come to us. For the general audiences to do that is extremely difficult, but when mentally challenged to invest yourself in the film can be in the end much more intellectually and emotionally rewarding. What’s sad is that in most mainstream movies, everything is done for us and it makes it easy for the audience to not have to invest any work towards the picture or the characters within the story. Most movies are cued on when to manipulate the audiences emotions and let them know when it is OK to cry or OK to laugh, because most movies treat audiences unintelligently. You know how many times I’ve watched a movie and when a scene that is attended to be funny occurs, everyone laughs or when there’s a scene that’s attended to be sad with the right melodramatic music everyone knew when to tear up. Alfred Hitchcock called these kind of movies ‘a machine for causing emotions’ in the audience. Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, Carl Dreyer, Andrei Tarkovsky and even Yasujirô Ozu’s approach is much different. They ask us to be patient as an audience and to take in the most we can from the characters and the story and at the end of it we arrive at our own conclusions on what we think. This is the cinema of empathy, which unfortunately isn’t done very often because it’s a more subtle artful approach to film making.

The biggest controversy with Bresson is how he trains his actors because he actually doesn’t train them at all. Bresson was known to cast nonprofessional actors and use their inexperience to create a specific type of realism in his films. He was known for creating the ‘actor-model’ technique and considered his actors less as actors and more as dolls. He forbids his actors to act or show much emotion. He was known to shoot the same shot 10, 20, or even 50 times, until all acting was drained from the characters faces, and eventually the actors were simply performing the physical actions and speaking the words. Much has been written about with Bresson’s rejection of actors, which remains, for many, an obstacle to enjoying his films. Bresson most famously didn’t like to shoot character’s faces as much as shooting the character’s fragmentation of their body parts through his framing; for which he focused on legs, torsos and hands which give the film a more naturalistic power. Bresson believed that actors, indeed acting itself, were alien to the medium of film, because the camera could detect the slightest sign of artificiality and calculation. This conviction not only proscribed the use of professional actors given to a familiar repertoire of facial expressions, physical gestures, and vocal inflections, it also ruled out the kind of nonprofessionals found, for example in Italian neorealism films, which were very popular at the time, who were encouraged to exude emotions and sentiments in order to emotionally move the viewer.

Bresson’s refusal to agree to a cinema dominated by the actor affected the overall look, structure, and tone of his films. Rather than grounding them in performances and dramatic scenes Bresson shifted the emphasis to the inherent aspects of the medium: the framing, duration, and editing of shots, and the use of sound and off-screen space. These were the features that determined the rhythm of a film’s movement toward its goal. In other words, for Bresson, the word performance did not refer to something that actors did but something the entire organic structure of a film did. In referring to his métier, therefore, he chose the word ‘cinematography’ over cinema, because the latter was associated with the more traditional form of dramatic filmmaking.

This doesn’t mean that Bresson was indifferent to his characters or the people who played them. It is more a matter of how he chose the latter. He sought people for their transparent innocence, their virginal presence before the camera, and the unstudied nature of their physical gestures. These qualities rendered them as pliable, as framing, lighting, and camera angles. As such, they were not actors at all, said Bresson, but ‘models,’ whose faces, hands, voices, and body language could be carefully fashioned, molded to fit the contours and audiovisual dynamic structure of each film. This approach, powerfully introduced a new kind of narrative filmmaking, which was soon labeled as ‘Bressonian,”and was a style adopted by many European filmmakers in subsequent decades. The economy, purity, and rigor of Bresson’s aesthetic are directly related to his vision of the world, a complex perspective that carefully balances a belief in free will against the notion of preexistent design.

A lot of people have criticised Bresson’s style of acting in his films and said his films are filled with emotionless zombies, but I disagree. By simplifying the performance to just have them do the action and speak the words achieves a unique purity that make his films more powerful. Because of having actors not show much emotion, it makes us want to feel more about them, and we than have to decide for ourselves what these characters are thinking and feeling, which I believe leads to much stronger emotions for the audience because we are now forced to empathize.

Bresson reveals the story of A Man Escaped in an unadorned style, completely devoid of special effects, dramatic thrills, elevated tension, and the use of known movie stars. Most filmmakers use those tools as an artistic way to manipulate and distract its audience, Bresson only uses the bare necessities that are needed to tell its story, and strips the audience of everything else. Bresson instead gives us a small cell, its four walls, a door, a high window, and a few Nazi guards patrolling the area. Film critic Roger Ebert states: “Watching a film like A Man Escaped is like a lesson in the cinema. It teaches by demonstration all the sorts of things that are not necessary in a movie. By implication, it suggests most of the things we’re accustomed to are superfluous. I can’t think of a single unnecessary shot in A Man Escaped.” Because of Bresson’s actor-model technique, the director did not want any facial expressions, physical gestures, and vocal inflections to come out of any of the performances, believing any slight form of eccentricity was unnecessary. He wanted the actor to simply embody the character, perform the physical actions as needed, look plausible when doing it, and try to not draw any undue attention from themselves. And so A Man Escaped creates character not through the actor’s performance but through the actions that are performed; as action becomes the character.

A good example of this technique is the opening sequence in which Fontaine is arrested by the Gestapo, and is being driven to prison. Though he maintains a relatively neutral expression, Fontaine’s actions and off-screen glances tell the story as the camera pans down from his face to his left hand, which is testing the car door handle. The crosscutting between Fontaine’s face and the road ahead testifies to this ongoing assessment of the situation. Without the benefit of traditional acting, dialogue, or voice-over we enter directly into the mind-set of the character and the style that will dominate the rest of the film. Fontaine’s acting method is similar to Bresson’s directing method, in which it involves the close scrutiny of salient details, without the need of zooms, intercuts or flashy camera effects that call attention to themselves. Bresson uses the basic vocabulary of close, medium and long insert shots, and the rest of it the audience can fill in for themselves. Because of this, Fontaine’s knowledge of his environment, is also our knowledge. We watch Fontaine sit in solitary confinement most of the day as he taps out messages in a code, or stands on a shelf to look out a high barred up window to talk with some of the prisoners on the courtyard. We watch how food plates enter and leave the premises, we discover how prisoners pass notes to one another as they routinely wash-up in the morning, and we can see the vague shadows of the Nazi guards when Fontaine peers through his peep-hole door.

Bresson doesn’t show much of the Nazi guards, and even though their figures appear in several shots, no real point is made of them. No guard becomes a character, and they’re no clichés about the sadistic guards or the friendly guards. Even the prisoners that Fontaine meets throughout the story don’t become too familiar to us and are only vaguely defined. Orsini and Terry are only helpful to Fontaine for a short period of time and Orsini gets killed when impatiently trying to escape, and Terry is simply transferred to another prison. Father Le Pasteur tries his best to give all the spiritual wisdom that he has over to Fontaine, while Fontaine passes some of it over to Blanchet, who without Fontaine, would have killed himself much more earlier if it wasn’t for Fontaine. And besides Fontaine’s new cellmate Jost, who could be either a potential danger or benefit to Fontaine’s escape plan, most of the character’s throughout the story come and go or are either quickly seen through passing; Fontaine even admits to mourning over the death of a prisoner he has never met before. If some prisoners are executed their death is either heard off-screen, or mentioned through other prisoners, as the violence in the film is never shown. Sound is used quite effectively off-screen, whether its to hear the execution of prisoners, or to elaborate on the oncoming danger that could be waiting for Fontaine, while he slowly listens to any approaching guard outside his cell while working to dismantle the cell door.

As Bresson intently has the audience invest in every minor detail, we watch Fontaine slowly devise a way to get through the door, and then, get over the wall. Even though Bresson strips the audience of all the necessities that most Hollywood films use to invoke feelings of suspense, mystery, and entertainment, he still effectively keeps the audience highly absorbed every step of the way. We watch in awe as Fontaine methodically and rhythmically takes apart his cell door, a window frame, his bedsprings, and patiently winds his bedclothes into rope, as we perceive these very acts as a form of attentiveness, creativity, diligence, fortitude, skill, patience, persistence and, not least, faith. Fontaine ultimately doesn’t attempt his escape alone, and he must either try to trust his new cell-mate Jont or decide to kill him. Similar to Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, there is a sparse narration that is read throughout A Man Escaped, which was presumably based on André Devigny’s. original book. A Man Escaped seems to be clearly mobilized by the protagonists will to be free, and at the same time Bresson said his aim was to “show the miracle of an invisible hand over the prison, directing what happens.” Thus, the propulsive trajectory of Bresson’s narratives, a result of the removal of excess and the refinement of technique which serves his overriding theme that human lives follow an implacable course. This is also apparent in such later films of his like Au Hasard Balthazar, Mouchette, and L’argent, despite their radically different subjects and increasingly cynical view of a world in which spiritual redemption seems to no longer exist. It’s quite an astonishing experience to see how a filmmaker can create one of the most intense and gripping films about a prison escape, even by removing all the formulaic things that many audiences feel necessary for the cinema; which in the end proves it is not.

As Bresson intently has the audience invest in every minor detail, we watch Fontaine slowly devise a way to get through the door, and then, get over the wall. Even though Bresson strips the audience of all the necessities that most Hollywood films use to invoke feelings of suspense, mystery, and entertainment, he still effectively keeps the audience highly absorbed every step of the way. We watch in awe as Fontaine methodically and rhythmically takes apart his cell door, a window frame, his bedsprings, and patiently winds his bedclothes into rope, as we perceive these very acts as a form of attentiveness, creativity, diligence, fortitude, skill, patience, persistence and, not least, faith. Fontaine ultimately doesn’t attempt his escape alone, and he must either try to trust his new cell-mate Jont or decide to kill him. Similar to Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest, there is a sparse narration that is read throughout A Man Escaped, which was presumably based on André Devigny’s. original book. A Man Escaped seems to be clearly mobilized by the protagonists will to be free, and at the same time Bresson said his aim was to “show the miracle of an invisible hand over the prison, directing what happens.” Thus, the propulsive trajectory of Bresson’s narratives, a result of the removal of excess and the refinement of technique which serves his overriding theme that human lives follow an implacable course. This is also apparent in such later films of his like Au Hasard Balthazar, Mouchette, and L’argent, despite their radically different subjects and increasingly cynical view of a world in which spiritual redemption seems to no longer exist. It’s quite an astonishing experience to see how a filmmaker can create one of the most intense and gripping films about a prison escape, even by removing all the formulaic things that many audiences feel necessary for the cinema; which in the end proves it is not.