La Strada (1954)

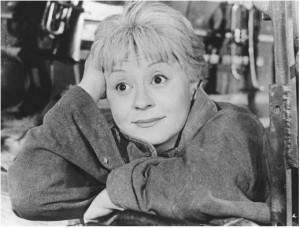

La Strada which in English means 'The Road' is one of Federico Fellini's most heartbreaking fables. It's a simple road film that contains the many 'Felliniesque' trademarks that we would return to throughout Fellini's career, which are the circus, the parade, the seashore, loneliness, the search for love, a figure suspended between earth and sky, and one woman who is a waif and another who is a monster. These iconic themes and images would be reworked and reused until the end of Fellini's life. The story of La Strada begins with a half-witted woman named Gelsomina, is sold by her mother to Zampano, a traveling circus performer, who entertains crowds by breaking an iron chain tightly bound across his chest. Gelsomina is played by Fellini's real wife Giulietta Masina, who brings to the character an innocence and warm naïvety. Her mannerisms, round-like clown eyes and adorable child-like facial expressions give off a "Chaplinesque" feel to the performance. Gelsomina's love and sweet innocence that the character embodies protects her from the harsh realities of the cruel world, until the murder of a 'fool' breaks down that protection and crushes her spirit forever. Zampano is a very controlling, and physically abusive man, played by the legendary actor Anthony Quinn, in probably his greatest and most powerful acting performance. The tragedy of Zampano is that he loves Gelsomina and does not know it, which is the central tragedy for many of Fellini's characters, in which they are always turning away from the warmth and safety of those who understand them. Neorealism, as a term, can mean several things; it often refers to films of working class life and of the struggles and social conditions of people set in the culture of poverty. [fsbProduct product_id='783' size='200' align='right']An immediate box office hit, La Strada won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and it catapulted its director, Federico Fellini, to the front ranks of that country’s greatest filmmaking talents. La Strada is looked at as the bridge between the postwar Italian neorealism movement which had earlier shaped Fellini with films like I Vitelloni, and Nights of Cabiria, and his later surreal like extravaganzas like La Dolce Vita and 8 ½. A lot of Catholics thought Fellini was making a sort of religious statement with the characters in La Strada. Gelsomina has a love for nature, insects and children and possesses a mystical innocent understanding of a saint. Zampano is considered the fallen human who she tries to redeem; and The Fool is the laughing tightrope artist from the heavens who has come down to give Gelsomina a purpose like the pebble; to serve and love Zampano. La Strada became an important film for many people over the years, especially director Martin Scorsese. He says in an interview on the Criterion DVD that he knew self-destructive characters like Zampano growing up as a child. Angry and violent, Zampano lashes out at the world around him making it impossible to love or be loved by another human being. A lot of Zampano's characteristics were brought over to several of Scorsese's character's throughout the years, most famously with the character of Travis Bickle in Scorsese's Taxi Driver, and Jake Lamotta in Raging Bull.

La Strada which in English means 'The Road' is one of Federico Fellini's most heartbreaking fables. It's a simple road film that contains the many 'Felliniesque' trademarks that we would return to throughout Fellini's career, which are the circus, the parade, the seashore, loneliness, the search for love, a figure suspended between earth and sky, and one woman who is a waif and another who is a monster. These iconic themes and images would be reworked and reused until the end of Fellini's life. The story of La Strada begins with a half-witted woman named Gelsomina, is sold by her mother to Zampano, a traveling circus performer, who entertains crowds by breaking an iron chain tightly bound across his chest. Gelsomina is played by Fellini's real wife Giulietta Masina, who brings to the character an innocence and warm naïvety. Her mannerisms, round-like clown eyes and adorable child-like facial expressions give off a "Chaplinesque" feel to the performance. Gelsomina's love and sweet innocence that the character embodies protects her from the harsh realities of the cruel world, until the murder of a 'fool' breaks down that protection and crushes her spirit forever. Zampano is a very controlling, and physically abusive man, played by the legendary actor Anthony Quinn, in probably his greatest and most powerful acting performance. The tragedy of Zampano is that he loves Gelsomina and does not know it, which is the central tragedy for many of Fellini's characters, in which they are always turning away from the warmth and safety of those who understand them. Neorealism, as a term, can mean several things; it often refers to films of working class life and of the struggles and social conditions of people set in the culture of poverty. [fsbProduct product_id='783' size='200' align='right']An immediate box office hit, La Strada won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film and it catapulted its director, Federico Fellini, to the front ranks of that country’s greatest filmmaking talents. La Strada is looked at as the bridge between the postwar Italian neorealism movement which had earlier shaped Fellini with films like I Vitelloni, and Nights of Cabiria, and his later surreal like extravaganzas like La Dolce Vita and 8 ½. A lot of Catholics thought Fellini was making a sort of religious statement with the characters in La Strada. Gelsomina has a love for nature, insects and children and possesses a mystical innocent understanding of a saint. Zampano is considered the fallen human who she tries to redeem; and The Fool is the laughing tightrope artist from the heavens who has come down to give Gelsomina a purpose like the pebble; to serve and love Zampano. La Strada became an important film for many people over the years, especially director Martin Scorsese. He says in an interview on the Criterion DVD that he knew self-destructive characters like Zampano growing up as a child. Angry and violent, Zampano lashes out at the world around him making it impossible to love or be loved by another human being. A lot of Zampano's characteristics were brought over to several of Scorsese's character's throughout the years, most famously with the character of Travis Bickle in Scorsese's Taxi Driver, and Jake Lamotta in Raging Bull.

PLOT/NOTES

La Strada begins with Gelsomina near the ocean hearing her mother calling her home. When she returns home her mother is crying saying, "Gelsomina, you remember Zampano who took Rosa away with him? She's dead, poor thing." Gelsomina looks at Zampano who has his back against the wall smoking a cigarette. "Were so poor, she's not like Rosa but she'll do what she's told. She just came out a little strange," her mother says to Zampano.

Zampano has returned to her village and is looking for another partner and since Gelsomina's sister died on the road with Zampano her mother sells Gelsomina to Zampano for 10,000 lire.

Her mother tells Gelsomnina she will learn a good trade while being on the road and it will be one less mouth to feed at home. Gelsomina is happy that she will travel and see the world like her sister and also be able to sing and dance. She tells all her neighbors goodbye as her mother cries when Gelsomina leaves on the back of Zampano's wagon waving to everyone, "Time to go"!

Zampano, is a harsh brute man (Anthony Quinn) who makes money living as an itinerant performer where he entertains crowds by breaking an iron chain tightly bound across his chest. During his show he always excites the audience by describing how dangerous his trick is. "If there's any delicate person in the audience, I would advise him to look away 'cause there could be blood!"

The first day on the road Gelsomina is impressed when watching him perform his show. All Zampano needs for his act is a person who can play the drum and trumpet, dance a bit and be a clown for the audience. Because Gelsomina is not too bright and the job doesn't take much skill, teaching her those simple antics shouldn't be a problem.

Zampano gives Gelsomina new clothes and gives her a form of rehearsal. Zampano has her try to say 'here he is: Zampano.' He then teaches her how to use the drums and announce him. When she struggles to get it right Zampano gets up and grabs a branch from the bushes. When she makes another mistake; he whips her with it, which is the beginning of his abuses towards Gelsomina; making her cry.

The first night with Zampano he asks Gelsomnia to sleep in his wagon but she doesn't want to. He yells "get in!" and throws her in the back. There is a sweet moment in the morning where Gelsomina is watching Zampano sleeping and she gives him a tender smile.

On the road Gelsomina eventually does learn to play the drums and soon enough they are both putting on a comedy show for the audience. At the end of each show Zampano says, "Thank you! And now my wife will pass the hat. Thank you for those that can give something and thank you for those who can't!" Gelsomina keeps asking Zampano if he will eventually teach her to play the trumpet because she's always wanted to learn; but for some reason he will never let her play it.

One evening the two of them go into a small bar while Zampano lies and tells everyone Gelsomina is his wife. Later that evening Zampano gets drunk and that's usually when he is his cruelest. Gelsomina tries to connect with Zampano and she asks him where he was born and he rudely says "my father's house."

During that same evening he hangs out with an old fling of his and he shows off by flexing his muscles and showing all the cash he has. When leaving he gets in his wagon with the woman and then strands Gelsomina telling her to wait there.

Gelsomina waits for him all night into the early morning. She starts to cry and when people ask her if her husbands the guy in the motorcycle with the wagon, they direct her to him down the street where she finds him passed out on the grass.

He finally wakes up suffering from a hangover and the both of them get back on the road. Gelsomina asks him if he was like this with his sister Rosa; running around with other women. Zampano says "If you want to stay with me, you've got to learn one thing-to keep your mouth shut!"

During their next show on the road a bunch of children from the town grab Gelsomina and take them to their house to show them their sick bed-ridden brother. There's a magical moment where Gelsomina in her clown make-up does a birdie dance for the sick child around a chair; making all the children laugh. Even though this film is neo realism; you can start to see the magical Felliniesque side slowly peering out between the seams; especially in this scene.

That evening Gelsomina is hurt yet again when Zampano spends the night with another woman and during that next morning she starts pouting at him. Eventually she tells him she's leaving and packs up and goes to the nearest small town.

She follows a parade into town where she comes across a public Catholic ceremony marching through the town and she is captivated. She is entranced by the parade's large canvases and paintings of Jesus and the large wooden crosses being carried through the streets.

She then happens upon Il Matto (The Fool), a talented high wire artist and clown putting on a show for the people in the town. Later in the night when the streets clear out Zampano drives in and finds her sleeping in the streets. He tells her to get in but she persists yelling, "I don't want to go with you again! I don't want to! Never again!" She tries to get away from him but he grabs her and throws her in the back of the wagon.

A few men are on the street watching the confrontation and Zampano threatens them saying, "You got something to say? I thought so."

Gelsomina wakes up the next morning to find herself and Zampano with a ragtag traveling circus and surprisingly enough The Fool who she saw the other night performing already works there. The Fool already knows Zampano from the past and keeps maliciously teasing Zampano with every opportunity he can get.

During one of their shows when Zampano and Gelsomina perform; The Fool purposely taunts him in the audience by shouting out obnoxious remarks during Zampano's stunt. This infuriates Zampano and after the show he goes after The Fool trying to violently attack him. That evening Gelsomina asks Zampano about him and The Fool.

"What has he got against you?"

"How should I know?"

"Did you do something to him?"

"I never did a thing to him. He's the one who makes fun of me. One of these days he'll pay for it."

"But who is he?"

"Bastard son of a gypsy, that's who he is."

"Have you known him long?"

"Too long."

Gelsomina likes The Fool and is curious by his goofy and strange personality and during the next few days he has connected with her with his goofy antics. He teaches her how to play the trumpet; which Zampano never allowed her to play and when Zampano sees this he is upset.

He angrily shouts, "she only works with me! I tell her what to do! If I tell you not to work with that bum, then you don't work with him! Because that's how I want it!"

Eventually The Fool takes his pranks too far and throws a pail of water at Zampano, which starts him going raving mad pulling out a knife and chasing him throughout the carnival.

Soon enough the two are arrested and jailed and Gelsomina starts questioning if she should stay with Zampano. The Fool is released early from jail because he didn't pull a knife. He comes back and sees Gelsomina. He asks her how she ended up with a man like Zampano. She says, "He gave my mother 10,000 lire."

There is a touching moment between her and The Fool where he says to her, "You know, Zampano wouldn't keep you if you weren't worth something to him. Maybe he likes you." She asks "Me?" The fool answers "Why not? He is like a dog. Ever seen those dogs who look like they want to speak but all they do is bark? If you don't stay with him, who will?"

One of my favorite scenes of the film is when The Fool tells her his theory on life. "I'm an ignorant man, but I read a book or two. You may not believe it, but everything in this world has a purpose. Even this pebble." When Gelsomina asks, "What's its purpose? " The Fool says, "It's purpose is... How should I know? If I knew I'd be the Almighty, who knows everything. When you are born. When you die... Who knows? No. I don't know for what this pebble's purpose is, but it must have one, because if this pebble has no purpose, then everything is pointless. Even the stars! And you too...You have a purpose."

Gelsomina holds the pebble in her hands and smiles thinking of what The Fool said. When he asks her if she will leave or stay with Zampano The Fool already knows the answer and drives her to the police station as she patiently waits for Zampano to be released from jail the next morning. For some reason or another Gelsomina loves this brute angry man, and with her innocence and love can see that behind all that anger is a man of pain and anguish.

When released and later on the road they ask some nuns in a convent if they can stay in their barn for the night; and they let them. That night in the barn Gelsomina asks Zampano, "Would you be sorry if I died? Once I really wanted to die 'rather than stay with him' I told myself. Now I'd be even willing to marry you since were going to stay together. If even a pebble has a purpose." Zampano says, "Enough of this nonsense! Go to bed. I'm tired." She then asks him, "Do you like me...a little?" He just ignores her comments and goes to sleep.

That same evening during a rainstorm Gelsomina wakes up to find Zampano quietly trying to steal a silver heart from the church but he can't seem to reach it through the bars because his hands our too big. He asks Gelsomina to be an accomplice in the theft but she says no pulling away from him; which leads to him angrily smacking her.

The film makes a drastic change when The Fool and Zampano cross paths once again, when The Fool is on the side of the road fixing a flat tire. Still angry at him for his past pranks, Zampano pulls over and confronts The Fool.

He then attacks him by punching him in the head while Gelsomina watches in horror. Gelsomina screams for him to stop and The Fool's head hits the side of the car. The last words of The Fool is, "you broke my watch," and he suddenly collapses and dies.

Zampano is in shock of his sudden death, and quickly moves to hide the body and then pushes his car off the side of the bridge. They then both get back on the wagon and quickly take off, while Gelsomina keeps shouting, "no!! no!!" Watching the killing of the innocent Fool destroyed Gelsomina's love and shattered her innocence, and over the next few days she remains unusually quiet and lifeless. They stop in a town and do one of their shows but she can't even bare to play the drums. During the act she just stands still and keeps saying over and over, "the fool is hurt..." Her behavior starts to scare Zampano.

Later in the day Zampano says to her, "What is wrong with you? No one saw us, and no one is after us. They'll never even expect us." Zampano then realizes that Gelsomina is frightened of him and won't even go near him. Zampano that evening asks her if maybe he should take her back to her mother, but she still doesn't answer. A few days later while cooking soup Gelsomina seems to be getting better and Zampano tells her, "I didn't mean to kill him. I just punched him a couple of times. I turn around; he drops dead. The rest of my life in prison for a couple of punches!" Suddenly Gelsomina starts crying again and says, "The Fool is hurt..."

That early morning Zampano takes out some extra clothes, blankets and lays them next to Gelsomina. He also leaves the trumpet that Gelsomina always loved to play; and then abandons her while she is sleeping.

Years later Zampano is traveling through a small town and overhears a woman singing a song that Gelsomina used to play with the trumpet when they both were on the road together. When he asks the woman where she got that tune she says, "a girl who was here a long time ago used to sing it. About four or five years ago. She always played it on the trumpet, and it stuck in my head."

When he asks where she is the lady says, "she's dead, poor thing. No one around here knew her or anything about her. She never spoke. She seemed crazy. My father found her one night on the beach. All she did was cry. Then one morning she didn't wake up. The mayor got involved, wrote letters to find out who she was."

One night after a show Zampano gets violently drunk at a bar and starts to pick fights with the other customers there. They throw him out and he pathetically stumbles near the shores of the beach. Suddenly all that emotion and pain that he's held inside begins to break away and he collapses right on the beach, breaking down and crying uncontrollably.

One night after a show Zampano gets violently drunk at a bar and starts to pick fights with the other customers there. They throw him out and he pathetically stumbles near the shores of the beach. Suddenly all that emotion and pain that he's held inside begins to break away and he collapses right on the beach, breaking down and crying uncontrollably.

NEOREALISM

Italian Neorealism came about as World War II ended and Benito Mussolini's government fell, causing the Italian film industry to lose its center. Neorealism was a sign of cultural change and social progress in Italy. Its films presented contemporary stories and ideas, and were often shot in the streets because the film studios had been damaged significantly during the war.

The neorealist style was developed by a circle of film critics that revolved around the magazine Cinema, including Luchino Visconti, Gianni Puccini, Cesare Zavattini, Giuseppe De Santis and Pietro Ingrao. Largely prevented from writing about politics (the editor-in-chief of the magazine was Vittorio Mussolini, son of Benito Mussolini), the critics attacked the white telephone films that dominated the industry at the time. As a counter to the popular mainstream films, including the so-called "White Telephone" films, some critics felt that Italian cinema should turn to the realist writers from the turn of 20th century.

Both Antonioni and Visconti had worked closely with Jean Renoir. In addition, many of the filmmakers involved in neorealism developed their skills working on calligraphist films (though the short-lived movement was markedly different from neorealism). In the Spring of 1945, Mussolini was executed and Italy was liberated from German occupation. This period, known as the "Italian Spring," was a break from old ways and an entrance to a more realistic approach when making films. Italian cinema went from utilizing elaborate studio sets to shooting on location in the countryside and city streets in the realist style.

The first neorealist film is generally thought to be Ossessione by Luchino Visconti in 1943. Neorealism became famous globally in 1946 with Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City, when it won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival as the first major film produced in Italy after the war.

Most neorealism films are generally filmed with nonprofessional actors--although, in a number of cases, well known actors were cast in leading roles, playing strongly against their normal character types in front of a background populated by local people rather than extras brought in for the film.

They are shot almost exclusively on location, mostly in run-down cities as well as rural areas due to its forming during the post-war era, no longer being constrained to studio sets. The topic involves the idea of what it is like to live among the poor and the lower working class. The focus is on a simple social order of survival in rural, everyday life. Performances are mostly constructed from scenes of people performing fairly mundane and quotidian activities, devoid of the self-consciousness that amateur acting usually entails. Neorealist films often feature children in major roles, though their characters are frequently more observational than participatory.

Open City established several of the principles of neorealism, depicting clearly the struggle of normal Italian people to live from day to day under the extraordinary difficulties of the German occupation of Rome, consciously doing what they can to resist the occupation. The children play a key role in this, and their presence at the end of the film is indicative of their role in neorealism as a whole: as observers of the difficulties of today who hold the key to the future.

Many of the films involved Post-synch sound/dubbing employing conversational speech, and local dialects. They also included funtional rather than ostentatious editing that would draw attention to itself, as shots were organized loosely. Many neorealism films involved stories that were episodic, elliptical, or organic in structure. Plot were preferable not a tight framework of cause and effect, but a more fluid relationship between scenes which approximated how events would occur in real life.

Many of the films had a sense of a documentary impulse & immediacy in filming, shifting away from the pretense of studio stories. It wanted to be a cinema that attended to the details and trials of everyday life, of the material experience of average people in difficult situations. It also had a concern with the lives of working-class people and a social commitment and humanist point of view to contemporary stories that spoke to the historical present. Vittorio De Sica's 1948 film Bicycle Thieves is also representative of the genre, with non-professional actors, and a story of a 'everyday man' and his hardships of working-class life after the war.

Italian Neorealism rapidly declined in the early 1950s. Liberal and socialist parties were having a hard time presenting their message. Levels of income were gradually starting to rise and the first positive effects of the Ricostruzione period began to show. As a consequence, most Italians favored the optimism shown in many American movies of the time. The vision of the existing poverty and despair, presented by the neorealist films, was demoralizing a nation anxious for prosperity and change. The views of the postwar Italian government of the time were also far from positive, and the remark of Giulio Andreotti, who was then a vice-minister in the De Gasperi cabinet, characterized the official view of the movement: Neorealism is "dirty laundry that shouldn't be washed and hung to dry in the open."

Italy's move from individual concern with neorealism to the tragic frailty of the human condition can be seen through Federico Fellini's films. His early works Il bidone and La Strada are transitional movies. The larger social concerns of humanity, treated by neorealists, gave way to the exploration of individuals. Their needs, their alienation from society and their tragic failure to communicate became the main focal point in the Italian films to follow in the 1960s. Similarly, Antonioni's Red Desert and Blow-up take the neo-realist trappings and internalize them in the suffering and search for knowledge brought out by Italy's post-war economic and political climate.

Neorealism screenwriter Cesare Zavattini said, "film should address not 'historical man' but the 'man without a label.' I dare to think that other peoples, even after the war, have what they continued to consider man as a historical subject, as historical material with determined almost inevitable actions...For them everything continued, for us, everything began. For them the war had been just another war, for us, it had been the last war...The reality of buried under the myths slowly reflowered. the cinema began its creation of the world. Here was a tree, here, an old man, here, a house, here a man eating, sleeping, a man crying...The cinema should accept unconditionally, what is contemporary. Today, today, today."

French film critic Andre Bazin on neorealism: "No more actors, no more story, no more sets, which is to say that the perfect aesthetic illusion of reality, there is no more cinema."

In the period from 1944–1950, many neorealist filmmakers drifted away from pure neorealism and into a period of "rosy neorealism" of Italian films of the 1950's. Some directors explored allegorical fantasy, such as de Sica's Miracle in Milan, and historical spectacle, like Senso by Visconti. This was also the time period when a more upbeat neorealism emerged, which produced films that melded working-class characters with 1930s-style populist comedy, as seen in de Sica's Umberto D.

There are different debates on when the Neorealist period began and ended. Some claimed it ended in 1948, with the shift in power from the left to the centrist Christian Democrat Party and with the inclusion of Italy in the Marshall Plan, which began to subsidize the film industry once more. Many claimed that the cycle ended with De Sica's Umberto D in 1952.

Robert Kolker suggests a useful way of thinking about "two Neorealisms. 1) on the one hand a group of films made between 1945 & 1955, and 2) on the other Neorealism as an idea, an aesthetic, a politics...both a form of praxis and an ideal to aspire to."

Irrelevant Actions were an aesthetic that neorealism provided. Andre Bazin essay on Umberto D saying, "the most beautiful sequence in the film, the awaking of the little maid, rigorously avoids and dramatic italicizing. The young girl gets up, comes and goes in the kitchen, hunts down ants, grinds the coffee...and all these 'irrelevant' actions are reported to us with meticulous temporal continuity."

More contemporary theorists of Italian Neorealism characterize it less as a consistent set of stylistic characteristics and more as the relationship between film practice and the social reality of post-war Italy. Millicent Marcus delineates the lack of consistent film styles of Neorealist film. Peter Brunette and Marcia Landy both deconstruct the use of reworked cinematic forms in Rossellini's Open City.Using psychoanalysis, Vincent Rocchi characterizes neorealist film as consistently engendering the structure of anxiety into the structure of the plot itself.

ANALYZE

A low-key mood study about a broken-down carnival strongman and his half-wit assistant traveling through the bleak backwaters of post-war Italy wouldn’t, at first glance, appear to have much going for it in the way of international critical and commercial appeal. But from the moment of its release in 1954, it was clear that La strada had everything.

An immediate box office hit, La strada won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. In Italy it catapulted its director, Federico Fellini, to the front ranks of that country’s greatest filmmaking talents. It revived the acting fortunes of its American star Anthony Quinn, and made his co-star, Giulietta Masina, a world-wide sensation. Nino Rota’s haunting musical theme for La strada poured from countless radios, juke boxes and record players. But far more important than these particulars of first rank success was the simple fact that this uniquely bittersweet comedy-drama touched people’s hearts in a way few films have managed to do. And, there is no question that it will continue to do so for years to come.

Federico Fellini began his career working with a traveling theater troupe before becoming (in succession) a radio gag writer, a cartoonist, a scriptwriter and assistant for such established Italian talents as Roberto Rossellini and Pietro Germi. His first features, The White Sheik (1952) and I Vitelloni (1953) suggested he was aiming to establish himself as a comic filmmaker. La strada consequently came as a surprise.

The “neo-realist” school of filmmaking (Rossellini’s Open City and DeSica’s Bicycle Thieves) had accustomed critics and audiences to dealing with the darker and more depressed areas of the post-war Italian scene, but La strada was different. These characters are certainly recognizable as human flotsam and jetsam, but no one would call them “ordinary.” Marginal in the extreme, they wind their way across a landscape so barren as to resemble one of De Chirico’s eerily surrealistic canvases. Likewise, Fellini’s treatment of their adventures and interactions doesn’t aim for a sense of commonality on the level usually associated with naturalism. There’s an odd touch of fantasy hanging about this childlike waif and the sullen brute who keeps her, and more than a touch of the magical to the circus high-wire walker known as The Fool, who they meet along the way.

It is clear that Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina) is mentally retarded. It is also clear that this mental state hasn’t destroyed her sense of self. Zampano (Anthony Quinn) may have bought her from her mother like a common slave, but it is Gelsomina who comes to understand the world and her place in it, not her brutish keeper. “Why do you want me?” Gelsomina asks Zampano —she’s not pretty, she’s not talented and he clearly doesn’t love her. But it is also clear that a man even on as low a level of the totem pole as Zampano needs something he can call his own—and that something is Gelsomina. The Fool (Richard Basehart) helps Gelsomina come to grips with this fact, and her place in the world as well. A catalyst in other characters’ lives, he gives Gelsomina hope. But his merciless teasing of the humorless Zampano precipitates the disaster that brings La strada to its tragic climax.

Fellini’s treatment of all of this is effortless and elegant. These particular characters may carry universal weight, but they’re never allowed to degenerate into cardboard symbols. Giulietta Masina’s clown-like face and comic timing inevitably recall Chaplin. But neither the actress nor her director press the point. La strada never presses any point. Like the characters’ realizations about themselves and the world, the meaning of La strada slips over you gradually, simply,unforgettably.

-David Ehrenstein

The idea for the character Zampanò came from Fellini's youth in the coastal town of Rimini. A pig castrator lived there who was known as a womanizer: according to Fellini, "This man took all the girls in town to bed with him; once he left a poor idiot girl pregnant and everyone said the baby was the devil's child." In 1992, Fellini told Canadian director Damian Pettigrew that he had conceived the film at the same time as co-scenarist Tullio Pinelli in a kind of "orgiastic synchronicity":

I was directing I vitelloni, and Tullio had gone to see his family in Turin. At that time, there was no autostrada between Rome and the north and so you had to drive through the mountains. Along one of the tortuous winding roads, he saw a man pulling a carretta, a sort of cart covered in tarpaulin... A tiny woman was pushing the cart from behind. When he returned to Rome, he told me what he'd seen and his desire to narrate their hard lives on the road. 'It would make the ideal scenario for your next film,' he said. It was the same story I'd imagined but with a crucial difference: mine focused on a little traveling circus with a slow-witted young woman named Gelsomina. So we merged my flea-bitten circus characters with his smoky campfire mountain vagabonds. We named Zampanò after the owners of two small circuses in Rome: Zamperla and Saltano.

Federico Fellini is considered one of the greatest directors in the world, and there's one main theme that he obsesses with over the course of his career – The Circus. He loved the circus as a kid and throughout his films you see homages to the circus and clowns – whether it's in La Dolce a vita, 8 ½, Juliet of the Spirits or Amarcord. His films; like the films of Hitchcock, Bergman, Kurosawa, Bunuel, Kubrick and Godard, all have signature styles in their movies, and Federico Fellini's films are definitely one of them. The character of Gelsomina is slightly similar to the role Giulietta Masina played later in Nights of Cabiria, but she of course in that film is a little more tough, less naïve, and has more spunk – probably because she played a prostitute. Both these characters are similar with their Chaplinesque like expressions, and both are looking for someone to love.

Even though Federico Fellini's themes are very similar, through his body of work overtime his style changed. His early work in I Vitelloni was more biographical, La Strada, and Nights of Cabiria had more of a Italian Neorealism feel to it. He slowly ventured off a little in his masterpiece La Dolce a Vita, and delved into more surrealism with 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits. La Strada became an important film for many people over the years, especially Martin Scorsese. He says in an interview on the Criterion DVD that he knew self-destructive characters like Zampano growing up as a child. Angry and impulsive, strong on the outside yet weak on the inside. All Zampano knows is his dumb circus routine, and in many ways is not much smarter than Gelsomina. Zampano lashes out at the world around him and makes it impossible to love or be loved by another human being. Even Gelsomina tries to reach out to him with her unselfish heart but can't pierce through his barbarian flesh to reach his soul. The only emotions he knows and understands is violence and because of that it destroys everyone around him. A lot of Zampano's characteristics were brought over to the character Travis Bickle in Scorsese's Taxi Driver, and most obviously the character of Jake Lamotta in Raging Bull. Scorsese even mentions the Fool and how he remembers people like him from his childhood. People that never took life seriously, and would push and push someone until the joke went too far. La Strada can be looked at as a simple road film but the tragic proportions and the emotional intensity of the story between these two tragic characters make it much grander. La Strada is a film that carries so many of Fellini's trademarks that he will use over and over again until the end of his career. The circus, the seashore, loneliness, the search for love, parades, and a figure suspended between earth and sky, and one woman who is a waif and another who is a monster. A lot of Catholics thought Fellini was making a sort of religious statement with the characters in La Strada. Gelsomina has a love for nature, insects and children and possesses a mystical innocent understanding of a saint. Zampano is considered the fallen human who she tries to redeem; and The Fool is the laughing tightrope artist from the heavens who has come down to give Gelsomina a purpose like the pebble; to serve and love Zampano. The amazing music in this film by Nino Rota is called "Travelling Down a Lonely Road", a wistful tune that appears in the film first as a melody played by the Fool on a kit violin and later by Gelsomina after she learns the trumpet. Its last cue is near the end of the film sung by the woman who tells Zampano the fate of Gelsomina after he abandoned her. The ending of La Strada is one of the most shattering endings in cinematic history. One night after a show Zampano gets violently drunk at a bar and starts to pick fights with the other customers there. They throw him out and he pathetically stumbles near the shores of the beach. Suddenly all that emotion and pain that he's held inside begins to break away and he collapses right on the beach, breaking down and crying uncontrollably. The ending is so powerful because what Fellini does is interesting. Most filmmakers would end the film on the 'hero' or 'victim' of the story. Instead of ending the film with Gelsomina, Fellini decides to end it with Zampano. Even though Zampano probably will go back and revert to the way he always has been, I believe this emotional breakdown is a sort of spiritual breakthrough for the character. And the genius of Fellini is that we find ourselves caring and pitying this man. At this point Zampano realizes he can never love, will always be alone, and the one person who would ever love him is no longer around to love him anymore.

Even though Federico Fellini's themes are very similar, through his body of work overtime his style changed. His early work in I Vitelloni was more biographical, La Strada, and Nights of Cabiria had more of a Italian Neorealism feel to it. He slowly ventured off a little in his masterpiece La Dolce a Vita, and delved into more surrealism with 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits. La Strada became an important film for many people over the years, especially Martin Scorsese. He says in an interview on the Criterion DVD that he knew self-destructive characters like Zampano growing up as a child. Angry and impulsive, strong on the outside yet weak on the inside. All Zampano knows is his dumb circus routine, and in many ways is not much smarter than Gelsomina. Zampano lashes out at the world around him and makes it impossible to love or be loved by another human being. Even Gelsomina tries to reach out to him with her unselfish heart but can't pierce through his barbarian flesh to reach his soul. The only emotions he knows and understands is violence and because of that it destroys everyone around him. A lot of Zampano's characteristics were brought over to the character Travis Bickle in Scorsese's Taxi Driver, and most obviously the character of Jake Lamotta in Raging Bull. Scorsese even mentions the Fool and how he remembers people like him from his childhood. People that never took life seriously, and would push and push someone until the joke went too far. La Strada can be looked at as a simple road film but the tragic proportions and the emotional intensity of the story between these two tragic characters make it much grander. La Strada is a film that carries so many of Fellini's trademarks that he will use over and over again until the end of his career. The circus, the seashore, loneliness, the search for love, parades, and a figure suspended between earth and sky, and one woman who is a waif and another who is a monster. A lot of Catholics thought Fellini was making a sort of religious statement with the characters in La Strada. Gelsomina has a love for nature, insects and children and possesses a mystical innocent understanding of a saint. Zampano is considered the fallen human who she tries to redeem; and The Fool is the laughing tightrope artist from the heavens who has come down to give Gelsomina a purpose like the pebble; to serve and love Zampano. The amazing music in this film by Nino Rota is called "Travelling Down a Lonely Road", a wistful tune that appears in the film first as a melody played by the Fool on a kit violin and later by Gelsomina after she learns the trumpet. Its last cue is near the end of the film sung by the woman who tells Zampano the fate of Gelsomina after he abandoned her. The ending of La Strada is one of the most shattering endings in cinematic history. One night after a show Zampano gets violently drunk at a bar and starts to pick fights with the other customers there. They throw him out and he pathetically stumbles near the shores of the beach. Suddenly all that emotion and pain that he's held inside begins to break away and he collapses right on the beach, breaking down and crying uncontrollably. The ending is so powerful because what Fellini does is interesting. Most filmmakers would end the film on the 'hero' or 'victim' of the story. Instead of ending the film with Gelsomina, Fellini decides to end it with Zampano. Even though Zampano probably will go back and revert to the way he always has been, I believe this emotional breakdown is a sort of spiritual breakthrough for the character. And the genius of Fellini is that we find ourselves caring and pitying this man. At this point Zampano realizes he can never love, will always be alone, and the one person who would ever love him is no longer around to love him anymore.